|

Mr. President, Ladies, and

Gentlemen: The Scotch-Irish have stamped an imperishable impression upon

Georgia. For those homely virtues of thrift, industry, and economy which

have caused the people of this state to be termed the Yankees of the

South; for that dauntless and invincible courage which has immortalized

the conduct of her soldiers upon the fields of battle; for all those

splendid qualities which enabled her people to erect the fabric of pure

and honest government out of the corrupting chaos of reconstruction, and

to move forward so rapidly and successfully in the march of progress as to

justly win for her the proud rank of the "Empire State of the South,"

Georgia is deeply indebted to that noble race in whose history, traced

through their career here, and their earlier settlements in the Carolinas,

Virginia, and Pennsylvania, back to old Ulster, and further still to the

lowlands and craggy highlands of Scotland, the electric search light of

the nineteenth century discloses not a single page blurred by servile

submission to native wrong or foreign yoke. [Applause.]

How deep is this debt is

not readily apparent. The youngest of the colonies, Georgia, has drawn her

population largely from her older sisters. The blood of several races

mingles in the veins of her people. Intensely American in their lives,

their characteristics and their habits of thought, they trace their

ancestry back to one of the older states that fought with England for the

liberty of this now great and powerful Union. And they could afford to

stop there. For what princeling in all Europe has so good a title to that

true nobility which should characterize a man as those whose ancestors

fought for liberty at Lexington and Concord, Trenton or Monmouth, King's

Mountain or Cowpens? The brilliant glory of the American revolution, by

the shadow it cast upon antecedent events, veils from view the earlier

ancestry of our people. But long before America was even discovered the

Scotch-Irish blood which poured out so freely in the battles of the

Revolution flowed in the veins of hardy and brave ancestors, who, from

prehistoric days, transmitted the power and the strength to their

descendants to withstand all forms of oppression.

For that ancestral pride

which rests supinely upon the greatness and the glories of the past, there

are no words but those of contempt; but in that ancestral pride, which

sees in the great deeds of past generations the incentive to purer lives,

higher purposes, and loftier ambitions, we have the strongest guarantee

for the perpetuation of our institutions. To-morrow will rise upon a Union

more homogeneous, and with less cause for sectional division, than ever

existed in the past. May I digress to add: May the great Protestant

Churches, which are now divided, become as indissolubly united as the

states! [Applause.] But below the surface there are evils which are

likely, in the not distant future, to grow to grave dangers; and there is

no such antidote for the poison lurking in the body politic as to drink

deep at the fountain of inspiration flowing from the noble lives and the

great deeds of the race to which we have the honor to belong. [Applause.]

With these sentiments I enter upon the pleasant task assigned me to-night.

It would be impossible to

give the number of Scotch-Irishmen in Georgia who have reached distinction

in every walk of life. My friend, Col. George Adair, read to you yesterday

a list of a few who have helped to build Atlanta. To read to you a list of

those who have contributed to the greatness of the state would more than

consume the session of our Convention. The limitations of the occasion

necessarily confine me to a few general remarks upon the part the

Scotch-Irish have played in the settlement and development of the state;

their contribution to its population; their influence upon its

civilization; and an observation or two pertinent to the facts presented,

and just a word in regard to the duty we owe the present and the future.

The illustrious character

and philanthropic motives of Oglethorpe threw a luster about the colony he

planted at Savannah. McMaster justly classes him as the most interesting

of all the men who led colonists to America. His fame shines resplendent

even by the side of the gifted Raleigh's. He was the associate of great

men. He lived in the public gaze. Heralded in advance by royal command,

every detail in the history of his colony was recorded by polished pens.

We can see the good ship "Annie" as she cast anchor off the bar of

Charleston on January 13, 1733, and the distinguished reception accorded

Oglethorpe by the authorities of South Carolina. We follow the colonists

to Beaufort; we note Oglethorpe's visit to Tomo-chi-chi; and we watch him

mark out the site of Savannah. We return with him to Beaufort and reembark

with the colonists. We stop with them on the way to regale ourselves with

the plentiful supply of venison awaiting their coming. The next day when

they cast anchor off the bluffs of Yammacraw, we hear the joyous words of

hope uttered by the destitute men who had been weighed down with

misfortune in crowded old England, as they set foot on unpeopled Georgia.

In what striking contrast

was the advent of the hardy pioneers who had left home and fireside, for

conscience sake, to seek liberty and freedom in the wildernesses of

America! They wrote their history with the rifle and the ax, the sword and

the plow! [Applause.] There was no herald of their coming save the splash

of the pole as they pushed the rude ferryboat across the upper waters of

the Savannah, or the crack of the whip as they urged their tired beasts

drawing primitive wagons over rough mountain roads. The record of their

coming was lost as the ripples of the river sunk back into its current, or

the echoes of the mountain died away in its silence. We know neither the

day nor the month nor the year when thousands came. But the fact that they

had come was attested by the falling of the trees. Cabins rose and

fruitful farms appeared where forests grew and Indians roamed. And not far

off the church—the house at once of worship and instruction. What man

reared in the country does not recall the old schoolhouse with its

backless wooden benches and the Sabbath morn at the country church! The

whole community gathered there. Some came on foot, some on horseback, the

better to do in wagons and old-fashioned carriages. With what reverence

they entered the old church! with what devotion listened to the minister!

And after church came the kindly greetings, the words of sympathy and

cheer. The highest and the lowest met on terms of equality. Such

communities knew not the much talked of aristocracy of the South. No-purer

democracy ever existed in the world.

Before my mind rises the

picture of an old stone church built in the last century, surrounded by a

beautiful grove of oak and hickory; and near by, the old graveyard, with

its fence crumbling to decay, and its rude stones mouldering in the dust

of time, marking in more than one instance the final resting place of men

of national reputation. Statesmen worshiped there; plain Scotch-Irishmen,

who helped to mold and sway the destinies of the nation.

Oglethorpe's colony

encountered many privations. It was threatened by Spaniards, it fought

with Indians, and it languished under restrictions more crushing than

either. Dark clouds gathered o'er its fated head, rent only here and there

by the arrival of fresh emigrants. Most noted among these were the brave

Scotch colonists, who, when told at Savannah that at the place chosen for

their settlement the Spaniards could fire on them from their fort,

replied: "Very well, we will take the fort and find homes already built."

[Applause.]

As I have said, I cannot

individualize, but who can speak of that colony without mentioning the

immortal name of Mcintosh. [Applause.] Who could fail to recall Gen.

Lachlan Mcintosh as he took charge of the first regiment in Georgia raised

to fight for American independence; or the reply of Col. John Mcintosh to

the English colonel 'who demanded the surrender of Sunbury under a threat

of destroying the town, "Come and take it" [applause]; or the gallant

James Mcintosh who fell at the head of his columns at Moleno del Rey.

In 1752 the trustees of the

Georgia colony, harassed by complaints, beset by difficulties, and unable

to maintain the colony, surrendered their privileges to the king. A year

later the entire white population is estimated to have been only 2,381. In

the language of McMaster, Oglethorpe's noble charity "had failed;" and in

the language of Bancroft, Georgia was indeed "the home of misfortune." But

English policy and English folly, operating in distant fields,

uninfluenced by the broad principles of philanthropy, but governed alone

by the narrow lines of bigotry and intolerance which would force men's

consciences to conform to the dogmas of an established Church, were then,

and had been for more than half a century, laying the foundation for the

independence of America and the greatness of this state. Thirty-eight

years later the site of old Ebenezer, the town of the Salzburger

settlement, was a cow pen; New Ebenezer scarcely more than a name.

[McMaster, Vol. II., p. 3.] Frederica was in ruins; Sunbury, which the New

England colonist had built with so much hope, had fallen to decay; the

Medway no longer bore upon its bosom the proud ship of commerce; and

Sunbury's docks slowly rotted away. And yet Georgia was a sovereign state,

a free compeer among the sisters of an independent republic, and its

population had grown to eighty-two thousand, fifty-two thousand of whom

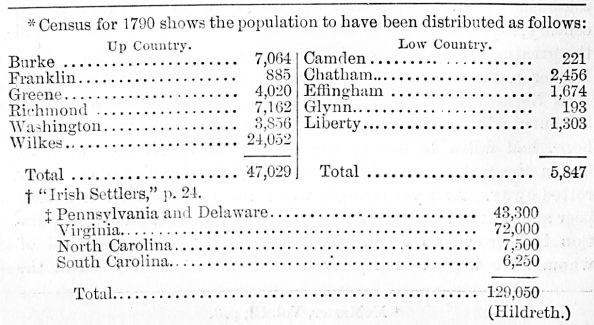

were whites. Forty-seven thousand of these lived in the counties of Burke,

Franklin, Greene, Richmond, Washington, and Wilkes.

Whence came these people?

Chiefly from the mountain and Piedmont regions of the Carolinas and

Virginia. And whence came their ancestors? The answer to that question

tells the part the Scotch and Irish have played in the settlement of

Georgia. To answer it properly we must take a brief view of the conditions

of the English colonies in America in 1689, the year after the revolution

that placed William and Mary on the throne of England. Here and there

along the seacoast from New England to South Carolina were scattered small

settlements. The total white population of the entire country was only

180,000. Of these the Scotch and Irish had already contributed a part.

Before that date, Froude says, began "that fatal emigration of

nonconformist Protestants from Ireland to New England, which, enduring for

more than a century, drained Ireland of its soundest Protestant blood, and

assisted in raising beyond the Atlantic the power and the spirit which, by

and by, paid England home for the madness which had driven them hither."

From 1689 the emigration from the North of Ireland assumed important

proportions. It is estimated that 100,000 emigrants left Ireland

immediately after the revolution. Three thousand males left yearly for

America. t And yet in 1702 the total white population of the colonies only

reached 270,000; and in 1715, with this emigration from Ireland steadily

going on, it only reached 375,000. At this latter date the total white

population in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, and South

Carolina—the colonies in which the Scotch and Irish principally

settled—was only 129,000.+

But it was not until some

years later that the Scotch-Irish emigration reached its flood; coming,

says Froude, from that character of people who were best calculated to

make Ireland great, "the young, the courageous, the energetic, the

earnest." "And the worst of it is," he adds, "that it carries off only

Protestants, and reigns chiefly in the north." Froude speaks of this

emigration as "an exodus," and it seemed destined to depopulate the North

of Ireland. * Ships came crowded to Charleston and to Philadelphia. In

1729 5,655 Irish emigrants arrived at the port of Philadelphia, and only

267 English, 43 Scotch, and 343 Germans. Ramsey states that Ireland

contributed most to the population of South Carolina; Williamson tells us

that the larger portion of the population of North Carolina came from

Ireland; and all historians agree that the great bulk of the Irish

emigration went into Pennsylvania, and thence to Maryland, Virginia, and

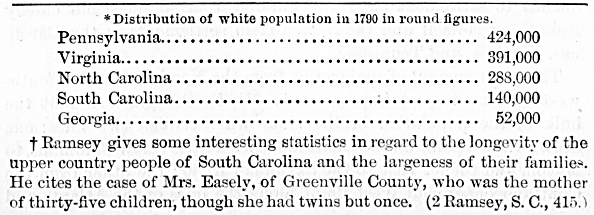

the South. This emigration continued for more than a century. And yet

after a century of emigration and a century of growth, the white

population of Pennsylvania, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia was only

1,285,000. * These early settlers were vigorous and long-lived. Their

families were large. They multiplied with rapidity. t A striking proof of

this is found in the present population of the Southeast, to which there

has been practically no foreign emigration for a century. In 1880 the

white population of Georgia was 816,000, and 323,000 persons born in the

state resided in other portions of the country. The increase in the

Carolinas and Virginia and the number of persons contributed by them to

other states is equally striking.

From the Scotch and Irish

settlements in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, flowed for more than

a century two streams of emigration: one along the west side of the

mountains through Tennessee and Kentucky to Alabama and the Ohio Valley;

the other down the east side of the mountains into the Carolinas, where it

met and mingled with the

current which had flowed in through Charleston and the Southern ports, and

pushed its way on into Georgia and across the mountains also into

Tennessee.

Thus it is established that

the Scotch and Irish from the North of Ireland largely predominated among

the early settlers of the mountain and Piedmont regions of the Southeast.

They and their descendants began to move into Georgia about 1773. In that

year Gov. Wright purchased from the Indians that portion of Middle*

Georgia lying between the Oconee and the Savannah. He at once took steps

to secure its settlement, and the liberal inducements then offered, which

were increased later, proved very attractive to the enterprising sons of

Virginia and the Carolinas. These emigrants, coming chiefly from the

highlands of the older states, settled almost exclusively in Middle

Georgia. As late as 1820 they were confined to that portion of the state

bounded on the east by the Savannah River, on the west by the Ocmulgee, on

the south by a line drawn from Macon east to the Savannah, and on the

north by a northeast and southwest line a little south of the Atlanta and

Charlotte road. Nearly the whole territory west of the Ocmulgee was still

in the possession of the Indians. In the next decade the emigration from

the Carolinas and Virginia, now greatly increased by that from Georgia

itself, moved on in a southwest direction to the Chattahoochee. In 1830 it

only extended to that river. By that date the other current of emigration,

moving down the west side of the mountains, had passed onward through

Tennessee into Alabama. Thus in 1830 a large area in the possession of the

Creeks in Alabama, extending from the Chattahoochee, below Columbus, to

the northern limits of that state, and a large territory in Georgia

contiguous to it, lying between the Alabama line and the west bank of the

Chattahoochee, in the possession of the Cherokees, was wedged in between

the currents of white emigration. Around three sides of it the

Scotch-Irish had already settled. When it was opened to settlement

emigrants entered from all sides, but chiefly from Georgia itself and the

Scotch-Irish settlements in the Carolinas, Virginia, and Tennessee.

The great current of

emigration from the Northeast to the Southwest left its deepest impression

in Middle Georgia. In 1850 the bulk of the population in the state was

between two lines: one drawn from a point on the Chattahoochee a little

below Columbus, to Macon, and thence east to the Savannah River; the other

from the Chattahoochee about West Point, along the lines of the Atlanta

and West Point and the Atlanta and Charlotte roads to the Tugalo River.

The same lines extended to the northeast would have included the majority

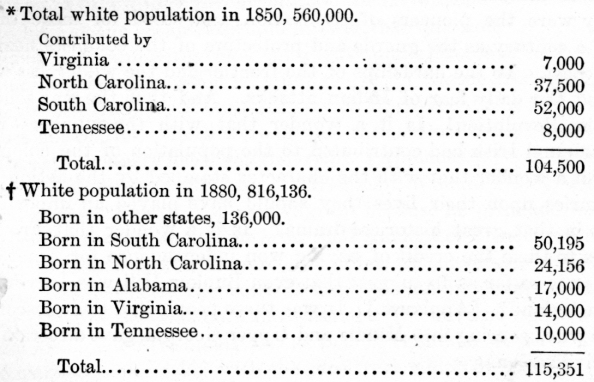

of the population of the Carolinas. By this date three-fourths of the

white population of the state was native born, but there was still a large

emigration from Virginia and the Carolinas. Tennessee, too, had begun to

add a goodly number. In 1850 there were 560,000 white people in the state.

One hundred and nineteen thousand of them were born in other states. One

hundred and four thousand of that number were contributed by the states

just named * South Carolina, whose up country population was

overwhelmingly Scotch-Irish, has nearly doubled every other state in the

number of emigrants she has contributed to Georgia. t

Having demonstrated, I

trust, that the mass of the people of the state have Scotch and Irish

blood in their veins, let us next consider the effect of the Scotch-Irish

upon its civilization. This has been produced by causes partly external,

partly internal. We cannot correctly estimate it without considering the

character of the race.

From the time when the

Scots left the North of Ireland to the period when the Ulster plantation

was settled in 1609 Scotland was one constant theater of war. The

sterility of the country, the clannish life its people led, the constant

dangers to which they were exposed, the frugal manner in which their

surroundings compelled them to live—all contributed to produce a brave and

hardy race. Alone frequently in the mountains, forced to rely purely upon

their own powers, there was developed in a marked degree not only physical

courage, but that high moral courage and self-reliance which

has so distinguished the

race and enabled it under all circumstances to stand so unswervingly for

what it believed to be right and made it ready to sacrifice home, family,

hope of emolument, life itself, for the dictates of conscience.

[Applause.] Love of individual liberty, devotion to homo and family ties,

the habit of reflection, promptness and decision in action, deep religious

convictions, belief in self-government, and a readiness to resist the

central power in the interest of the clan were characteristics naturally

growing out of the environment of the Scots. They were frequently overrun

by stronger and more numerous forces, but they were never conquered. The

sturdiness, endurance, and persistency of the race enabled them to

surmount every form of conquest and oppression. The moment the pressure of

superior power was removed the rebound occurred, and Scotland was again in

arms fighting for her rights. The indomitable courage of the Scots was

invincible. Their natural characteristics could not be destroyed, even by

merger with other races. The Dane, the Saxon, and the Norman settled in

Scotland, and their blood is liberally intermingled in the veins of the

Scotch, but the. virility of the Scotch blood has preserved its

distinctive national traits. Not even centuries of union with England

could destroy these. The Scots were stronger for their life in Scotland,

better for the blood of the Pict, the Dane, the Saxon, and the Norman.

When they returned to the North of Ireland, they found nothing there to

weaken or enervate, but much to temper and to strengthen. Transplanted to

the wilderness of America, their environment was as well calculated to

develop their courage, independence, and sturdiness of character as the

lives their ancestors had led in Scotland. They were the pioneers of

civilization, and stood for more than half a century as the guards and

protectors of the colonists nearer the coast. To the hardships of the

frontier and the wilderness was added the daily fear of Indian attacks.

And then the war school of the Revolution! Is it a wonder that with the

numbers the Scotch and Irish had contributed to the population of the

colonies —is it a wonder that with the character stamped by the action of

centuries upon their lives they should have played an important part in

that great historical drama? Is it a wonder that Froude gives to them the

credit of having won independence for America, and goes so far as to

suggest that even Bunker Hill was borrowed from Ireland? [Applause.] It

was these people and their descendants who, pouring into Middle and Upper

Georgia, gave direction to its civilization.

But before we pass to the

consideration of the part they have played in local affairs we should note

a few general events of far-reaching importance. In the cabinet of

Washington a "West Indian Scotchman, Hamilton, a Virginia Scotch-Irishman,

Jefferson, laid the foundation of political divisions which have run

through all party lines from that day to this. In the days of

nullification two Scotch-Irishmen, born near each other in South Carolina,

led opposing forces, impressed their distinctive views upon all sections,

and created wide political differences and stanch followers in this state

and throughout the country. When it came to the sad civil war, it was a

Scotch-Irishman whose mother was a Georgian the Confederacy chose as her

leader; and it was a Scotch-Irishman, I believe, from the place where he

was born, the Virginia county from which his father moved, and all his

surroundings—his personal appearance, his traits of character—who, from

the Presidential chair, controlled the sentiment of the North, and carried

her victoriously through the struggle of their respective sections. Both

men typical in the highest degree of the two civilizations.

Is it a wonder that the

Scotch-Irish, prominent in these stirring political events, should have

made an impression upon the history of this state?

Leaving the political

field, let us consider a moment the material development of the century.

Here too the Scotch-Irish have had an influence extending throughout the

whole country. The first steamship that crossed the ocean sailed from the

port of Savannah. A Scotch-Irish boy rendered that possible. Who can

estimate the influence of Pulton's invention upon the civilization of the

century? Go look at the ocean racer and answer that question.

The telegraph wires cover

continents, underlie oceans, and outstrip time in the transmission of

intelligence. A Scotch-Irish brain conceived telegraphy. Whether Henry or

Morse is entitled to the credit does not matter. Both were of this race.

But to the Scotch-Irish Morse the country has given the credit.

[Applause.] Prof. Morse was the great grandson of the Scotch-Irishman,

William Finley, who was driven from New Haven as a vagrant because he

preached without special authority, to become later the President of

Princeton College.

Although separated hundreds

of miles, we converse with ease and recognize distinctly the voice of him

with whom we talk. Alexander Graham Bell was born in Scotland. We have no

right to claim him as a Scotch-Irishman, but as Scotch-Irishmen we have a

right to claim close kindship with the race from which he sprung.

Thomas A. Edison—go listen

to his phonograph reproduce the human voice or the sweet symphonies of

music, and remember, when you do, that he too, on his mother's side, is a

Scotch-Irishman. [Applause.]

In politics, in the

development of the world, in giving this great government with its

beneficent institutions to mankind, in the control of those forces which

have revolutionized modern civilization, Scotch-Irishmen have led.

[Applause.]

We cannot overestimate the

effect of these external influences created by the brains and directed by

the hands of Scotch-Irishmen upon the development and civilization of the

state.

Within the state the race

has been equally potential in molding its destinies. Most notable among

the earlier settlements in upper Georgia were two on the Broad and

Savannah Rivers. From Virginia came the Gilmers, Lewises, Strothers,

Harvies, Mathews, Mer-iwethers, Bibbs, Johnsons, Crawfords, Barnetts,

Andrews, and McGhees; from North Carolina the Clarks, Dooleys, Murrays,

Waltons, Campbells, Gilberts, Jacks, Longs, Cummings, Cobbs, and

Dougherties. For years those colonists dominated Georgia. They gave tone

to its civilization. They gave direction to its politics. Their

descendants are scattered over the state and over the South. While we

cannot claim all of them as members of our race, it predominated.

It would be invidious,

where there have been so many great men, to specify any particular one,

but there are Georgians who believe that William H. Crawford should head

the list. [Applause.] Gov. Clark and Gov. Troup led the opposing parties

for years. Troup had the gallant Scotch blood of Mcintosh in his veins,

and it showed itself when he proclaimed: "The argument is exhausted; we

stand by our arms." And Clark was a Scotch-Irishman from North Carolina.

Later, during the exciting

political period that immediately antedated the war, we find the matchless

Benjamin H. Hill speaking for the nation. [Applause.] We also find that

sharp, shrill voice of one who showed the race from which he sprung, when

he declared that in politics he "toted his own skillet," raised for the

Union. No man was more independent in character, and no man has left a

greater impression upon the history of the state than Alexander II.

Stephens. [Applause.] Governor, speaker, cabinet officer, general, Howell

Cobb was the equal of any man in the Union. [Applause.] The peer of either

in intellectual ability, nearer even to the people of that day than his

great rivals, was the Scotch-Irish boy who had driven his wagon from South

Carolina into Georgia: Joseph E. Brown. [Applause.] When the war came on

and men buckled on the sword, what two soldiers on either side fought

harder, more bravely, or more gloriously than Longstreet and Gordon.

[Applause.]

And since the war, "in the

piping times of peace," who have contributed more to the material

development of the state than the plain Scotch-Irish citizens; who, when

the war was over, settled quietly down to work? [Applause.] They have

written their history in their achievements.

We cannot estimate the

influence of the Scotch and Irish upon the civilization of the state

without giving special consideration to the part men of that blood have

played in educating the people and directing their religious convictions.

Who can estimate the influence of such men as Bishop Elliott and Bishop

Pierce and Moses Waddell, and hundreds of others whom I wish I had time to

mention—among them the noble Scotch-Irish ministers of this city of ours

who have contributed so much to elevate its morals and advance its

civilization? Nor have I time to mention the names of the eminent

Scotch-Irishmen who have presided over our schools and colleges, but it is

interesting to note the number of men of Scotch-Irish descent who have

been trustees of the State University. The first four Presidents were

Scotch-Irishmen: Joseph Meigs, John Brown, Robert Findley, and Moses

Waddell. From 1801 to 1827 Scotch-Irishmen presided over that institution;

and to Moses Waddell specially is due the education of many of the men of

this state who have attained national reputations.

In every field of labor and

of thought the Scotch-Irish of the state have distinguished themselves.

The field of individual effort and success offers a rich mine for the

Scotch-Irish historian of the state. But I must content myself with the

statement that at the bar and on the bench, in medicine and in surgery, in

the pulpit and and in the press, in business of every character, men with

Scotch-Irish blood in their veins have taken foremost places. They have

furnished the majority of the Governors of the state since 1786. [The

following Governors are said to have been of Scotch and Irish descent:

John Houston, George Walton, Stephen Heard, George Matthews, John Milledge,

David B. Mitchell, Peter Early, George M. Troup, John Clarke, George R.

Gilmer, Wilson Lumpkin, Charles J. McDonald, George W. Crawford, George W.

Townes, Howell Cobb, Joseph E. Brown, Charles J. Jenkins, Alexander H.

Stephens, Henry McDaniel, John B. Gordon, William J. Northen.] At present,

with that characteristic of taking no more than they can get, they fill

nearly every Statehouse office. The Governor, the Treasurer, the Secretary

of State, the Commissioner of Education, . the Chairman of the Railroad

Commission, the Commissioner of Agriculture, the Librarian, the Adjutant

General, and a majority of the members of the Supreme Court, the final

custodian of our rights, have Scotch-Irish blood in their veins.

From the facts presented it

is clear that the white population occupying the mountain and highlands of

this state and the Southeast are entirely homogeneous. This entire section

is inhabited by men of English, Welsh, Scotch, and Irish blood, who,

descended from revolutionary ancestors, naturally have the clearest

conception of the genius and spirit of our institutions and the most

ardent love of individual liberty and local self-government. Schooled for

generations by hardship and adversity, they retain in the highest degree

the vigor of the races from which they sprung.

I know it is sometimes

thought, and sometimes said, that the Southern people are not active,

energetic, and enterprising; that they have lost the vigor of the old

stock. This is a mistake. Let the hard-fought battles of the civil war and

the history of this state for the last quarter of a century, with all its

splendid achievements and the rapidity with which these people have

rebuilt the waste places bear testimony. Let the activity, enterprise, and

progress of this beautiful city testify. Col. Adair called attention

yesterday to the fact that in a canvass made by Mr. Grady it was

discovered that most of her prominent men were natives of this or

adjoining states. Let me give you another proof: In the census of 1880

there were 37,000 people in Atlanta. All but 1,400 were born in America,

and all but 2,400 more were born in Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and

Tennessee. [Applause.]

There is another fact which

should be borne in mind. The Scotch-Irish carried with them to "Ulster,

when they were plain Scotchmen, the art of manufacturing. They caused

"Ulster to flourish with factories. Much of the same skill and the same

ingenuity to be found in the population of this whole section is now

wasted. Remember the great inventors to whom I have alluded, and then

remember that the Scotch-Irish race of Georgia and the surrounding states

is capable of the highest skill. Utilize it, and one day the Southeast

will reach the highest rank throughout the world in manufacturing.

[Applause.] You know your natural advantages; the present points to the

races to which you come, and says: "No people are capable of higher

attainments. Open the doors of future greatness."

But the duty of our race is

higher than that of developing the mere material prosperity of the

country. The preservation of the great principles for which our

forefathers fought is our noblest duty. They were brave and courageous,

they were noble and true. In the contests of the future let us emulate

their example. Upon the purity, simplicity, and temperance of our lives we

must rely for the transmission to unborn generations of the physical

strength required to withstand the fierce competition that will exist in

this state and country when hundreds shall have become thousands, and

thousands millions. Upon the church and the schoolhouse and the college we

must rely for the deep moral conviction and the high mental endowment

which will enable posterity to meet and solve the problems of the future.

Upon strict adherence to principle and courageous defense of right we must

rely for the maintenance of those institutions which give to the central

government all the powers necessary for the general welfare, and reserve

to states and communities the exercise of that local self-government

absolutely essential to individual freedom. May each succeeding generation

through distant ages bless their fathers for the transmission of these

traits of character and the preservation of this priceless form of

government [Prolonged applause.] |