|

Seizure of Island of St. Martin—Life in the West Indies—

Demerara and Berbice—St. Lucia—Depleted ranks— Service in India—Campaign

against the United States— Changes in uniform.

We must now return to the doings of the first battalion.

In February 1801 it sailed for the West Indies to : take part

in the expedition against the Swedish and Danish islands. Sweden and Denmark

had joined with Russia in an armed neutrality in the interests of France and

against England. Lt.-General Thomas Trigge was in chief command, and on

March 24 a landing on the Danish island of St. Martin was made successfully.

The Royals were to the fore, but the Governor showed more discretion than

valour, and after his surrender the battalion was divided. Six companies

remained there in garrison, and four went on to the capture of St. Thomas

and Santa Cruz. A home letter of this time from St. Martin’s, written by

Lieut. John Gordon of the regiment, gives a picture of life on these

colonial expeditions and shows that fighting was tempered by occasional

diversions—

"I intended to have written to you by last Packet, but a

sudden call to leave the island on business prevented me. I have now been

near three months in this country, and tho’ I cannot say I am much in love

with it, I think I shall stand the climate. We are fortunate in being

stationed in this island, which is one of the healthiest i$ the West Indies.

Some of the captured islands are quite the reverse, particularly St. Croix,

where the 64th Regiment, which came out along with us, has already lost

three officers, and upwards of 150 men. There is four companys of the Royal

detached at St. Thomas, and we have lost there two officers and 50 men; our

loss here is one officer and seventeen men. The officer we lost here went to

St. Thomas to pass a few days with his friends, and only lived one day after

his return. Tho’ this island be healthy, it is one of the hottest in the

country. The heat is so excessive, that we can scarcely stir out of the

house from nine o’clock in the morning till three in the afternoon. The

inhabitants here like the British Government and pay us every attention.

Colonel Nicholson of ours is Commandant of the Island, and the Council have

voted him £2,000 Sterling a year for his table. He gave a Ball and Supper on

the 4th inst., in honour of His Majesty’s birthday wnich cost him 300

guineas. It was known in the Island for several weeks that he was to give a

Ball on that day, and the Ladies, who are excessively fond of finery, were

at uncommon pains on this grand occasion. There was many dresses which I was

told (and from their appearance I don’t doubt it) cost upwards of £150

Sterling."

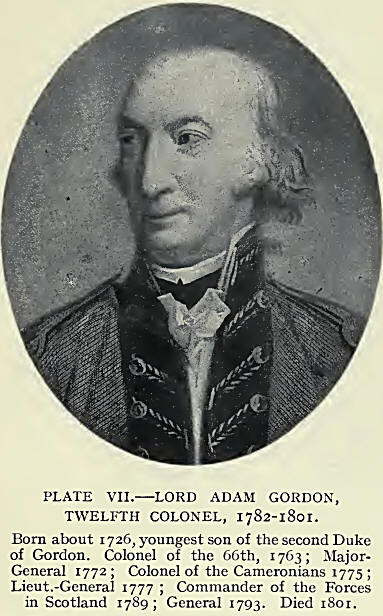

In August 1801 General Lord Adam Gordon died, and was

succeeded in the Colonelcy of The Royal Regiment by his Royal Highness the

Duke of Kent, from the 7th Royal Fusiliers.

A return dated 1802 shows that of 1290 men in the battalion

223 were “convicts, culprits, and deserters.” Many of these, doubtless, were

Irish rebels, good fighting material, but an awkward team to drive. The West

Indian captures did not long remain British, for by the Treaty of Amiens

they were restored to their original owners. Some of The Royals were moved

to Antigua. Others were quartered at St. Kitts in 1803, when war broke out

again in July.

In September, 650 of The Royals, with other troops, went on

an expedition against the Batavian Republic in South America. There was no

fighting, for Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice surrendered, and in 1804

Major Hardyman was complimented on his skill in getting the Dutch prisoners

to enlist on the British side.

From 1805 to 1812 the first battalion was on garrison duty at

various West Indian stations and at Demerara and Berbice, varied by

occasional fighting, but not of sufficient importance to merit detailed

description.

Meanwhile, the second battalion had gone, in 1803, to the

West Indies with the expedition against the French island of St. Lucia. The

Royals led a Fig. 16.—Private’s gallant assault with the Sixty-fourth

against the strong post of Morne Fortunee, and carried it with the bayonet.

The pluck of one officer deserves especial mention. Captain Johnstone, who

had already been wounded in Holland and in Egypt, owing tc his lameness from

the last-mentioned wound, was carried at the head of the light company and

literally thrown into the fort, which he was the second man to enter. The

Royals altogether did so well that the King added “St. Lucia” to the Colours.

The island of Tobago surrendered without fighting in July. They remained on

garrison duty in Tobago and Dominica during 1804, and there and in other

islands in 1805, where they met some of the first battalion. They were back

in England by January of 1806, their ranks tragically depleted; indeed the

strength was returned as “1 rank and file fit, 53 sick, 30 on command,

704 wanting.” The deficiencies were partly made up during 1806 from their

own third and fourth battalions (of which more hereafter), and from other

regiments. The latter source shows that the First Foot were popular.

Early in 1807 grave difficulty arose with the Sepoys in the

service of the East India Company, and the spirit of insubordination was

rife throughout India. The second battalion was ordered to embark, and

filled its ranks from the third and fourth battalions. The voyage was long

and trying, and the story is set out in a journal kept by the Fife-Major of

the regiment, who was on board the transport Coutts. There was great

scarcity of water, and in consequence much sickness. They had been five

months afloat when The Royals landed at Penang, or Prince of Wales Island,

on September 18, for their first Indian service. The barracks were temporary

sheds, lightly built of stakes covered with cocoanut leaves. As the diarist

picturesquely says: “When it came to blow hard, the barracks had the

appearance of waving corn in harvest.” Beds there were none, and the buffalo

beef and rice was very sorry fare, which made the soldiers “long for the

flesh pots of that land we had left.”

The Grenadier company, which had sailed in the Surat

Castle, had an even longer and more eventful voyage. The ship was so leaky

that she parted with the main fleet, and if the Grenadiers had not worked

the pumps night and day as she made for Rio Janeiro she would certainly have

gone down. Presumably the exercise was useful, for they had little sickness,

but one was struck down by a thunderbolt, and another killed by the natives

of an island where they touched for soft water. On this latter adventure,

the landing party only got back to the boat by the skin of its teeth. Many

of them were a good deal battered in the retreat, and some remained on shore

as prisoners of the natives. This did not please The Royal Scots, so they

landed again fully armed and marched to the town where the King lived. The

natives did not like the look of them, and there was no opposition until

they got into the presence of his Majesty. One of them, named John Love,

then took the trembling Nabob by the neck and shook him like a rat. At this

point the royal suite made prudent haste to restore the prisoners to their

angry messmates, and so all returned on board in great content. By the end

of the year, six hundred and thirty-one of the regiment were at Madras, and

three hundred and forty-one at Penang, where many died of disease. By the

following February, the adventurous Grenadiers arrived and joined the rest

of the battalion at Wallajahabad, but the climate started to make short work

of the whole regiment, and they sought salvation by going to the sea at

Sadras. By that time they could only muster five hundred effectives, and in

the first day’s march three hundred of these fell sick, chiefly of brain

fever. This was going from bad to worse, so they turned tail and marched

back to Wallajahabad, carrying with them a hundred and fifty men who were

unable to march.

The sergeant who has already been quoted was also careful to

set down how the spiritual needs of the battalion were met. “We had prayers

read for the first time since we came to this country, by the Adjutant, who

had fifty pagados a month for doing the duty of chaplain. But this was, I

think, little short of making a mock of the divine ordinance, for here was

truly ‘like people, like priest.'"

It is to be hoped that the Adjutant was, in a more recent

phrase, “an ecclesiastically-minded layman,’’ because the return of births

shows it was part of his duty to baptize all the children born in the

regiment. In any case, it is clear that the adjutancy of The Royal Scots was

no sinecure.

The battalion was in garrison and on campaign at various

places in India from 1809 to 1816, but saw very little active service during

this period. That does not mean that they had an easy time. The constant

moves were trying work, as the roads through the jungles were no more than

rough tracks, and rations were very irregular both in quality and quantity.

The troops always travelled barefoot, because no shoes were obtainable and

the tracks were sand or puddles, and a march of sixteen miles would often

take nine hours. There was some excitement during 1811, when the battalion

was quartered at Masulipatam. There were murders and suicides by men who had

run amok, and a still less pleasant incident was a plot engineered by the

Roman Catholic privates against their Protestant comrades, which, however,

was discovered before mischief was done. At this time only about thirty per

cent, of the men were Scots as against about fifty per cent. Irish, and the

rest English. The year 1812 brought a slight diversion, when four companies

were sent to Quilon, in Travancore, to suppress a mutiny amongst the

Company’s native troops. The year 1816 was the last of comparative quiet,

but the second battalion’s exploits in 1817 must be dealt with in chapter

XV.

We now return to the doings of the first battalion. The

strong sympathy between France and the United States, and the help which the

States rendered to Napoleon in carrying out his policy of destroying British

commerce, led to a state of war between Great Britain and the States in

1812. The first battalion of The Royals was ordered to proceed to Quebec

from Demerara and the West Indian islands over which it was scattered. At an

inspection which took place in June, it was clear that the battalion was not

in good fettle for active service. It contained three hundred of the rawest

recruits, and two hundred and twenty-six privates were on the sick list.

Discipline cannot have been of the best, for the inspecting general found

that there had been a hundred and fifty-three courts-martial. This is hardly

to be wondered at, for there was much opportunity for racial bickering. The

battalion was now Scots only in name, for of the total strength of twelve

hundred, five hundred and five were Irish, three hundred and fifty-two

English, and fifty-six foreigners. They set out for Canada in seven

transports, but one of them, the Samuel and Sarah, carrying three officers

and a hundred and fifty-six rank and file, was captured by an American

privateer. The report of the master of the ship, one Samuel Sower, has

survived. When the enemy frigate approached, the mate who kept the watch

thought it was the ship of the commodore of the escorting British squadron.

When its captain invited Sower to heave to, he replied that he must first

signal to his commodore. To this the Yankee answered that any such

proceeding would result in a broadside which would sink the transport. Sower

then consulted with Lieut. Hopkins, who was in command of The Royal Scots,

and, as they agreed that the smallest signal or resistance would be attended

with great slaughter, they yielded the ship as a prize. The American captain

stipulated that the whole of the arms and ammunition should be given up, and

that the troops should give their parole not to serve against the United

States unless regularly exchanged, but the officers were to retain their

swords. Master Sower had to ransom his ship by giving bills for twelve

thousand dollars, but, that done, they were allowed to proceed to Halifax.

By September, their parole was cancelled by the exchange of the crew of a

captured Yankee ship.

The rest of the year was taken up with marching and

counter-marching, but there was no fighting.

In January 1813 the battalion was divided between Montreal

and Quebec, and its composition was again exercising the minds of the

headquarters staff. Lt.-General George Provost wrote to the

Commander-in-Chief about the great number of Frenchmen serving in the

regiment. He considered them “a very improper class of soldiers to serve in

Canada, where the French language was so generally spoken, and the habits

and manners of the mass of the population assimilates the French.” In May, a

small detachment of the battalion was engaged in the attack on Sackett’s

Harbour, and in the following month two companies seized a strong post

occupied by the Americans at Sodus, where a quantity of stores was captured.

Four companies of the battalion then enjoyed a change of service, for they

were embarked on board the fleet to serve as marines. From July to October

the rest of the battalion was busy with skirmishing engagements, and in

December the Grenadier company assisted in the storming and capture of Fort

Niagara. They sustained no loss, but it was a brilliant bit of work and won

them high praise. After this success five companies crossed the Niagara

river and were employed on December 29 in storming the enemy batteries at

Black Rock and Buffalo. This time they did not escape so easily, for they

had fifty-one casualties, mostly incurred while they were landing from batteaux under

a heavy fire. Their courage and skill in these operations is the more

notable when it is remembered that they were carried out in the rigours of a

Canadian winter and without any of the comforts which soften such work for

modern armies.

Early in 1814 the battalion was posted on the enemy’s

frontier, but they did not get to close quarters until the beginning of

March. A strong body of Americans was then posted at Long Wood, near

Delaware town, well fortified on a hill and protected by timber breastworks.

The light companies of The Royals and of the Eighty-ninth (now merged in

Princess Victoria’s Royal Irish Fusiliers) made a frontal attack in a most

gallant manner, while some *other detachments attempted flanking movements,

but unfortunately they had to retire without dislodging the enemy. No more

success attended a severe engagement on July 5, in which The Royals lost

seventy-eight killed and a great many more wounded. This reverse was

followed by the surrender to the enemy of Fort Erie. None of The Royals,

however, was in the garrison, and they returned to Fort George at the end of

July. They took part in the violent engagements near the Falls of Niagara,

when the British division under Lieut.-General Drummond, himself an old

Royal Scot, was attacked by the Americans. Drummond’s official report of the

engagement is full of praise for The Royals, who behaved with perfect

steadiness and intrepid gallantry, and excited his warmest admiration. Still

better, the enemy’s attack was repulsed and his retreat considerably

harassed. The distinguished bravery then shown was rewarded by the royal

permission to bear Niagara on the colours of the regiment. In August the

British attacked Fort Erie, but with no success, and eight companies of The

Royals carried out with great steadiness the trying duty of covering the

retreat. In September the enemy made a sortie, and it was largely owing to

the fine performances of the regiment that it was driven back, but at the

cost of the life of Lt.-Colonel Gordon.

In January 1815 the battalion left Fort Niagara for Queenston,

and later for Quebec, but peace soon followed with the United States, and

they sailed for England in July.

About eighty years afterwards, on July 25, 1893, the remains

of three soldiers of The Royal Scots, found on a farm near Niagara, were

reburied with fitting solemnity at Lundy’s Lane, when Canon Houston, in an

eloquent address, rehearsed the gallant deeds of the heroic Scots.

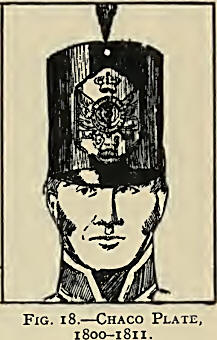

The beginning of the century saw a great change in the

uniform of the army. In the year 1800 the time-honoured cocked hat was

discarded in favour of a cylindrical chaco of lacquered felt with a leather

peak and an upright tuft or plume. On the chaco was fixed a thin brass

plate. This applied not only to the battalion and light companies, but also

to the Grenadier company when not wearing the bear-skin cap (see Fig. 15).

Side views of the privates’ and officers’ chacos are shown in Figs. 16 and

17, and of the chaco plate in Fig. 18.

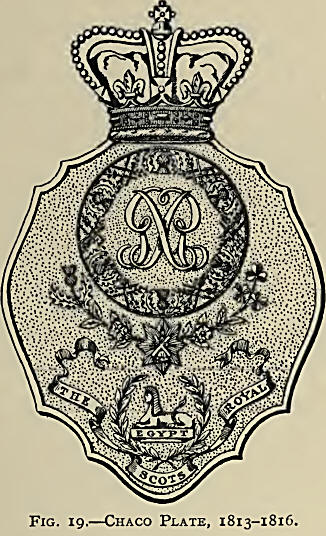

When the title of the regiment was changed early in 1812, to

“The Royal Scots,” the new chaco was furnished with a plate, illustrated in

Fig. 19, with the Sphinx to commemorate the Egyptian campaign. The pattern

of belt-plate established in 1800 seems to have lasted until 1816 (Fig. 20).

There are two especial points of interest in the arming of

The Royals during this period. In May 1796 an order was issued directing

that officers’ swords should be straight and made to cut and thrust, but the

regiment certainly did not conform with this, as the sword used had a blade

of the Andrea Ferrara pattern (Fig. 21). It is possible that this type was

used by officers in The Royals before 1796, but it is clear that during the

Peninsular War the regimental sword was unique in the British Army. In 1812

also The Royals wore a gorget, the last decorative survival of defensive

armour, which was distinguished from that used by other regiments by reason

of the ornaments being “laid on” instead of engraved (Fig. 22).

|