|

James VI has been presented in popular

historical tradition as a figure of fun, uncouth in appearance, a coward

and a fussy and foolish pedant. 'The wisest fool in Christendom' is one of

the better known historical judgments on any political personality. This

caricature is just that, and is the work of English writers who found

James's alien ways amusing when he came to be among them. Judged by his

record he was one of Scotland's most successful rulers. Taking full power

himself, in theory, in 1580, and in practice from 1582-83, he concentrated

on two main tasks - to increase national prosperity and to settle the

church. In both he met with reasonable success, though his church

settlement was always under threat.

In pursuit of commercial improvement he

pursued a mildly protectionist policy intended to give encouragement

especially to textile production - wool and linen. Export of Scottish wool

was prohibited and the import of dyes and oils useful in cloth-making was

freed from customs duties. Foreign craftsmen were encouraged to enter the

country to pursue their own profit and to train Scots in the skills which

they could display. The country's finances were more efficiently managed

and the Crown's income increased by the annexation to the crown of lands

which in past ages kings had given to the church. James now reclaimed

them.

Administration of justice was conducted

with zeal and efficiency as always

King James VI & I,

artist unknown 'detail' (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

Edzell Castle. (Photo: James

Halliday)

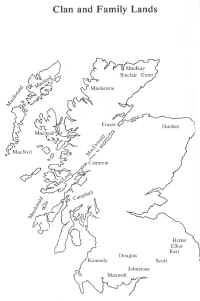

in areas like the Highlands where the years

of unrest in the state had undone much of the work of James IV. Highland

chiefs were required to find sureties for the good behaviour of their

subordinates, and had to produce evidence for their right to hold their

lands. New burghs were established at Campbeltown, Inverlochy and

Stornoway. An attempt to introduce settlers from Fife into Lewis and

Harris was not a success, the murder of some of the incomers by displeased

islanders proving a deterrent to the recruitment of others.

Politically James's reign saw growth in the

status and importance of Parliament. In 1587 the shires were granted the

right to representation, and an increasing amount of business was now

transacted in Parliament, where shire and burgh representatives were

present, rather than in the Great Council of which they did not enjoy

membership.

The result of these policies - and the

diplomatic policy of peace and conciliation which went with them - gave to

Scotland the first reasonably enduring period of prosperity for many a

year. In this atmosphere optimism was possible, and Scottish merchants and

gentry felt it safe once again to build houses which were not likely to be

demolished in civil disorder or English invasion. Sir David Lindsay's

castle at Edzell, and Sir George Bruce's 'Palace' at Culross belong to

this period, and stand as rather touching reminders of how ready Scots

were to respond to any reasonable prospect of peace and private happiness,

both so long denied.

But, of course, controversy there was,

particularly over the development of the church. When James came to the

throne, and throughout the period of his minority the church was something

of a mongrel. It was not Catholic, as Papal authority and the Mass had

both been rejected; but equally it was certainly not Presbyterian. Bishops

and Abbots still remained among the clergy and many were still Catholic in

their own personal opinions. In 1572 a compromise was

'The Palace', Culross.

(Photo: James Halliday)

agreed whereby bishops were to be retained

and nominated by the crown, but to be examined and accepted by committees

of reformed ministers; and the bishops were to be subject to General

Assemblies - the Presbyterian highest church authority - in matters of

belief and teaching.

In the mid 1570s this compromise was

attacked by the Presbyterian faction in the church led by Andrew Melville.

In 1578 Melville's Second Book of Discipline offered a Presbyterian

structure to the church; and in 1580 the General Assembly, meeting in

Dundee (consistently since the 1550s a centre of Protestant militancy),

condemned the office of bishop as unscriptural and unacceptable. The

General Assembly of 1581, meeting in Glasgow, confirmed the Dundee

decisions and seemed ready to move to adopt a full Presbyterian pattern.

But for this to be done the state would have to approve the changes, and

this the king and Council were not prepared to do.

At this point politics intruded upon

religious debate when in 1582 the General Assembly was so unwise as to

record its approval of the seizure of power and the king's person by the

extreme Protestant faction led by the Earls of Mar and Gowrie. The success

of this Raid of Ruthven (the king had been held in Ruthven Castle) was

short-lived and the Presbyterian hopes were dragged down in defeat

together with the faction which the Assembly had unwisely supported.

There followed for the next twenty years or

so a process of ebbing and flowing as Assemblies and Parliaments moved

nearer to Presbyterianism or further from it. The king, however, had made

up his mind. Intellectually he rejected the Presbyterian pattern, largely

because it was at total variance with his concept of monarchy. James

believed himself, like all monarchs, to be chosen by God, and saw himself

therefore the proper leader of his people in their religious as in their

worldly lives and practices. This idea of royal supremacy was wholly

unacceptable to Presbyterians who believed, theoretically at least, in

equality of all worshippers in the eyes of God. They rejected any

distinction between clergy and laity, or any hierarchy in the church.

James and Melville had a memorable confrontation on this very issue in

1596, during which Melville seized his king by the sleeve, for emphasis no

doubt, calling him 'but God's silly vassal' and informing the outraged

James that in the kirk, the kingdom of Christ, 'King James the Saxt, is

nocht a king, nor a Lord, nor a heid, but a member.' James never forgot

that incident which clearly convinced him that Presbyterianism and

monarchy could not co-exist.

In 1597, taking clever tactical advantage

of the General Assembly's request that the church should be represented in

Parliament, James agreed promptly, and invited the bishops to serve in

Parliament as the church's representatives.

This was the position, when in 1603

Elizabeth of England died and James, who had painstakingly cultivated

good, humble relations with the English queen, was called to the throne to

which his mother had aspired. She and Darnley had been Elizabeth's

rightful heirs, and now their son enjoyed the inheritance.

Enjoyed is the right word to use. There was

no such thing as a 'Union of the Crowns'. The king of Scots merely, and

personally, inherited an additional office, which paid much better than

his old one. The two kingdoms were in no sense united, and Scotland was

left in the hands of managers while her king went off to better himself.

In England his standard of living was higher. The respect accorded him was

vastly superior to anything he had experienced in Scotland. In England,

monarchy James found, was more like what monarchy should be. And

furthermore, he could now put Presbyterians in their place.

One of his first acts as king of England,

was to summon to Hampton Court delegates who would devise for the church

in England a structure to which all would be asked to conform. At the

conference one delegate was unwise enough to mention some merits for

Presbyterianism. 'A Scottish presbytery,' said James ('somewhat stirred'

as the report tells us), 'as well agreeth with a monarchy as God with the

Devil . . . Jack and Tom and Will and Dick shall meet and at their

pleasures censure me! . . . I will apply it thus, my lords the bishops . .

. if once you were out and they in place I know what would become of my

supremacy. No bishop, no king.' And with that statement of principle and

political conviction, King James presented the challenge which cost his

grandson and his family the throne. For the rest of the century, if any

man was hostile to episcopacy he must be ready to extend his hostility to

the crown, and to expect hostility in return. Similarly, if anyone were to

seek to limit royal power, he must be prepared to face the hostility of

the episcopal establishment. Just as James's mother and grandparents had

entangled the crown with the Catholic church and the French alliance, so

now James and his successors had bound monarchy and episcopacy into a

political alliance which none could see to break.

While events went his way in England, James

was able to take pride in the state of affairs in Scotland. 'This I must

say for Scotland, and may truly vaunt it; here I sit, and govern with my

pen, I write, and it is done; and by a clerk of the council I govern

Scotland now which others could not do by the sword.' James's very absence

from Scotland was really an advantage. Free from pressures and arguments

he simply passed on his wishes to his officials, who saw them carried out.

But James had qualities of shrewdness and administrative cunning which had

given his Privy Council in Scotland tasks which were manageable and goals

which were attainable. When he died in 1625, and was succeeded by solemn

and politically incompetent Charles I, it quickly became clear that the

success of James's system could be attributed in the end to the man who

devised it.

Charles

shared his father's notion of Divine Right, and his belief that kings

should be immune from the kind of criticism and correction appropriate for

lesser mortals, but he had none of his father's understanding of how far

and how fast he could go in pursuing his objectives. He wanted to enhance

the wealth and status of the church as it now existed, with its episcopal

structure. He wanted to bring order and conformity into that church, and

he chose to help him Archbishop Laud of Canterbury, one of these

tidy-minded souls who see some virtue in having everyone do the same thing

in the same way at the same time. Uniformity was the aim of archbishop and

king, and that uniformity they wished to extend to Scotland as well. Charles

shared his father's notion of Divine Right, and his belief that kings

should be immune from the kind of criticism and correction appropriate for

lesser mortals, but he had none of his father's understanding of how far

and how fast he could go in pursuing his objectives. He wanted to enhance

the wealth and status of the church as it now existed, with its episcopal

structure. He wanted to bring order and conformity into that church, and

he chose to help him Archbishop Laud of Canterbury, one of these

tidy-minded souls who see some virtue in having everyone do the same thing

in the same way at the same time. Uniformity was the aim of archbishop and

king, and that uniformity they wished to extend to Scotland as well.

Charles's financial requirements had

aroused annoyance among landowners, and his deference and favour shown to

churchmen, including his appointment of Archbishop Spottiswoode to the

office of Chancellor, annoyed the nobility who had grown accustomed to

seeing politics treated as a secular activity in which laymen might expect

any preferments. In 1634 the Scottish Parliament presented to Charles a 'Supplication'

in which grievances were stated, and the king was invited to alter his

political course. Obstinate and self-righteous Charles would not budge. In

1637 heated controversy arose over the use of the new Prayer book which

Charles now required to be used in Scottish churches. The response of the

Scots in February 1638, was to produce the National Covenant. It is a

long, and in general, dull document, but its signatories bound themselves

to maintain the form of church government most in accord with God's will

(Presbytery in other words) by force if necessary. This is what made the

Covenant a revolutionary document.

From the challenge there sprang the Bishops

Wars of 1639-40, and in seeking to provide himself with the strength

necessary to put down the Scottish rising, Charles had to call into

existence his English Parliament which alone could provide him with the

money which his planned military campaign would cost. He found that the

House of Commons would grant him money only upon conditions, and this

began the series of events which culminated in the outbreak of Civil War

in England in 1642.

The conflict in Scotland soon merged into

this Civil War, as Scottish factions found themselves taking sides and

making alliances with their English counterparts. In 1643 the majority

faction in Scotland, supporters of the National Covenant, entered into an

agreement with Charles's English adversaries whereby a Scottish army would

be sent to assist the Parliamentary forces receiving in return a guarantee

that, if the king were defeated, Presbyterianism would be not only secured

in Scotland, but imposed in England and Ireland as well. To this agreement

was given the name of 'Solemn League and Covenant', and in pursuit of this

improbable objective a Scottish force played a major role in the defeat of

the Royal army at Marston Moor, which effectively lost Charles the north

of England.

Other Scots too, however, were active in

the king's cause. When the Bishops' Wars began there was a very

united front against the king; but a civil war which aimed at the defeat

of the king and a threat to the monarchy as such, roused conflicting

opinions. James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, was Presbyterian in sympathy,

and had been a leading signatory of the National Covenant. He had shown

himself a vigorous and gifted military commander during the fighting in

Scotland, but he had come to realise that his colleagues were aiming not

just at a Presbyterian establishment, but at a drastic curbing of the

power of the king, if not indeed the actual destruction of the monarchy.

His suspicious hostility was aroused in particular by the behaviour of the

nobleman who had emerged as leader of the Covenanter party, Archibald

Campbell, Marquis of Argyle. With very little encouragement from the king,

Montrose formed a Royalist army in Scotland and, with assistance from

Alistair MacDonald - 'Colkitto' - and his men from Ireland, he inflicted

upon the Covenant's armies and upon Clan Campbell, a series of crushing

defeats. Despite his successes - at Tippermuir, Kilsyth and Inverlochy -

Montrose's brilliance was not enough to win against the battle-hardened

Scottish forces which, withdrawn from England, met and destroyed the

Royalist army at Philiphaugh. Royal defeat at Naseby virtually ended the

war in England, and Charles surrendered to the Scots in their camp at

Newark. His hope, possibly, was to play off the Scots against their

Parliamentary allies, but he was unsuccessful. The Scots, albeit with

reluctance, and under what amounted to threats, surrendered their prisoner

and left England. They were unwise enough to accept their expenses for

their costs in the war, and provided jibing Royalists in years to come

with the jingle 'Traitor Scot, sold his king for a groat.'

While in custody, Charles maintained

contacts with many of those moderate opponents who did not feel happy to

see Scotland under Argyle, and England under the religious extremists, who

were increasingly influential in Parliament. One such group of Scots,

under the Marquis of Hamilton, invaded England on the king's behalf but

were crushed by the English army at Preston in 1648. It was this episode

which cost Charles his life. He had invited on to English soil a foreign

army, and many hundreds of Englishmen were now dead who would have been

alive but for his actions. Pointing to what in another person would have

been treason, the English military leaders were able to have Charles put

on trial and executed in January 1649.

The execution of the king proved to be a

mistake of the first magnitude. The Scots, feeling perhaps responsible for

Charles's fate, and aggrieved because they had not been at all consulted,

now changed sides. The King's heir was recognised as Charles II on

condition that he would observe the National Covenant and the Solemn

League and Covenant. This action brought upon the Scots an English

invasion led by England's foremost military leader, Oliver Cromwell, who

crushed the Scots at Dunbar. In one last desperate fling, the young

Charles II, crowned the King of Scots by Argyle himself, conducted a

counter invasion of England only to see his army broken at Worcester.

Charles fled into exile, and Cromwell and his generals proceeded to

conquer Scotland. A victory at Inverkeithing, and the successful storming of Dundee by General George Monck, gave

England military control, and for the first time ever English forces

really had conquered Scotland. Scotland was incorporated into the English

state and Parliamentary system, there to remain, until the death of

Cromwell, and political confusion in England prompted General Monck to

lead his army to London, and call the survivors of the English Parliament

into session to resolve the crisis. That Parliament, as Monck knew it

would, invited Charles II to resume the throne, and the monarchy was thus

restored in 1660.

The now victorious royalists, in both

England and Scotland, came back to power with natural thoughts of revenge.

All those who had played any part in the revolutionary successes were seen

as beaten traitors upon whom retribution might properly fall. In Scotland,

the major target was Argyle. He had certainly changed sides and supported

Charles II, but this was not sufficient to erase royalist memories of the

other actions, including the defeat and execution of Montrose who had made

a more genuinely royalist attempt to claim Scotland for Charles II in

1650. Argyle now followed his great rival to the scaffold in Edinburgh.

Revenge was now carried out by legislation.

The Restoration meant more than simply the return of the monarchy. By the

Rescissory Act in 1661 all legislation passed since 1633 was declared null

and void. This meant that both the Covenants were renounced, and an

Episcopal church was re-established. Episcopacy had three crucial features

- hierarchy of Bishops; lay patronage (the right of landowners to appoint

the parish clergy) and royal supremacy (the king as 'head' of the church).

By 1669 specific Acts of Parliament had restored all three features.

What was now to become of those who refused

to accept the new arrangements? Parish ministers were ordered to submit

themselves for reappointment by the new Bishops. Some 300 refused, and

were 'outed' from their charges, their places going to men prepared to

serve, enthusiastically or resignedly, within an episcopal system.

Crown policies and episcopal church

government were now more clearly than ever closely inter-connected, and

opposition to one inevitably involved opposition to the other. A convinced

Presbyterian now found it diffficult to be an obedient subject, and a man's

religious zeal could almost be measured by the extent of his disloyalty to

the king.

Those whose consciences prompted them to

disobedience began by refusing to attend church services held under the

new authority, attending instead services conducted by an 'outed'

minister. This disobedience was met by a series of fines. Non-attendance

at the official services was punished by a fine; attendance at

non-official services was punished by another fine. These non-official

services were conducted in private houses or premises, and became known as

'conventicles'. Everyone attending a conventicle was liable to a fine; and

heads of families were held responsible for the behaviour of their

dependants. In due course they were even held responsible for the

behaviour of their tenants or servants. The fines were on a scale so harsh

that a family incurring them all, would very rapidly be economically

ruined.

So,

secrecy became desirable, and conventicles came to be held not in private

buildings, but in the open air, in some spot remote enough to avoid

detection. Outed ministers were compelled by law to move twenty miles from

the pulpits which they had previously occupied, and, as conventicles

continued, a new law provided that ministers conducting such services were

to face the death penalty. Thus there now began another great national -

or at least local - tradition; ministers, fugitives, with a price on their

heads, worshippers in breach of the law, and armed guards protecting the

conventicles against the possibility of attack from royal military

patrols. When death is the penalty to be faced, then hunted men and their

defenders will more readily inflict death upon their pursuers. So,

secrecy became desirable, and conventicles came to be held not in private

buildings, but in the open air, in some spot remote enough to avoid

detection. Outed ministers were compelled by law to move twenty miles from

the pulpits which they had previously occupied, and, as conventicles

continued, a new law provided that ministers conducting such services were

to face the death penalty. Thus there now began another great national -

or at least local - tradition; ministers, fugitives, with a price on their

heads, worshippers in breach of the law, and armed guards protecting the

conventicles against the possibility of attack from royal military

patrols. When death is the penalty to be faced, then hunted men and their

defenders will more readily inflict death upon their pursuers.

The actual holding of conventicles was not

in itself the major cause of worry to the authorities; officials' anxiety

was aroused rather by what was there said and discussed. Sermons tended to

deal with contemporary issues, albeit thinly disguised as commentaries on

events recorded in the scriptures. 'Preaching to the times' was how they

put it. Villainous rulers in ancient Israel, and biblical examples of

tyranny and persecution, were used to teach lessons which were not lost

upon the congregation. So discontent simmered, conventicles continued, and

patrolling soldiers policed the disaffected areas, notably Fife and the

south-western countries. John Graham of Claverhouse, one of the military

commanders, once remarked irritably that there were in Galloway 'as many

elephants and crocodiles as there are loyal and regular persons.'

If discontent and sedition smoulder away

for a long period the instinct of governments is usually to try to bring

the unrest out into the open where it can be crushed. By 1677 the

authorities were frustrated and infuriated by the

The Covenanters' Prison,

Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

prolonged nature of Presbyterian resistance

to which there seemed no foreseeable end. From the Bishops there came the

suggestion that the restless areas should suffer some 'notable corporal

punishment in terrorem' which would probably provoke a rising, expose the

ringleaders, and 'render them inexcusable'. With this aim there was

dispatched into Ayrshire in the spring of 1678, an army of irregular

soldiers recruited from the estates of Royalist lairds and nobles of Angus

and South Perthshire, to which history has attached the rather misleading

name of 'The Highland Host'. They were to maintain themselves by

confiscation - living off the land in military terms - an army of

occupation in effect. The result for the southwest in loss of produce,

financial damages and physical assault and intimidation, was considerable.

But, there was no rising. The whole object

of the exercise had failed and by the end of the year The Highland Host

was withdrawn. At this point when the attempt to provoke rebellion had

failed, events played into the hands of the government. On 3 May 1679 a

group of extremist Presbyterians in Fife ambushed and murdered Archbishop

James Sharp of St. Andrews - a vigorous supporter of royal policy, a

zealous extorter of fines, and, as former parish minister in Crail, a

turncoat enjoying enormous unpopularity. The murder had disastrous

consequences. The murderers fled, some of them to seek shelter with

friends in the west, and the royal dragoons went looking for them.

Thus it was that, on 1 June, Claverhouse

and a small force came upon a large conventicle at Drumclog on the

Lanarkshire/Ayrshire border. Believing that some of the assassins were in

the congregation, Claverhouse attacked, but the conventiclers proved

strong enough to beat him off. Rebellion was now a fact. Government forces

mustered in Glasgow, and Presbyterian recruits came

The Covenanters' Memorial,

Rullion Green. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

forward to join the rebel army which now

openly stood for 'The Good Old Cause' of the Covenants. An army, generally

accepted as being from 4-5000 strong, faced the Royalist force under

James, Duke of Monmouth, one of the king's sons, across the Clyde at

Bothwell Bridge on 22 June. The result was disastrous for the Covenanters.

Disunited and squabbling, they failed to prevent the advance of the royal

army and their ranks were speedily shattered.

Bothwell Bridge gave the government all the

advantages that had for so long proved elusive. Presbyterians could now be

treated as virtual traitors, and moderates and extremists alike had to

submit to the triumphant severity of the Crown and its instruments. The

main body of Presbyterians was cowed and submissive, and 'The Good Old

Cause' was dead as far as the mass of the population was concerned.

Resistance continued, but it now came only from a tiny minority of

extremists - and potential martyrs. |