|

From around 1650 the dominant power in western

Europe was France, and the Stewart kings were satellites of the French.

The coming of King William - a Dutch patriot whose life's work was to

obstruct French expansion and save the Netherlands - had carried England

into the anti-French alliance. This foreign policy was continued by

William's successors, and, as a result, wars with France were more or less

constant from 1690 until 1815. At times British success was spectacular,

especially in 1763 when Britain became a great imperial power, influential

in Europe and in virtual control of North America and India.

These wars, as we have seen, had major

economic consequences, encouraging the development of kelping in the

Highlands, and textiles and iron-founding in various parts of Scotland. In

commerce too, the growth of British colonial power offered many new

opportunities which many Scots accepted. Men of wealth, investors and

merchants, were first to seize these opportunities, but in time humbler

persons found ways to benefit. Many went as colonists to farm on land of

their own, to find careers in trades or professions, or to serve as agents

for British trading interests in New York or Philadelphia, Madras or

Bombay. Industries like cotton (and, later, jute) production,

sugar-refining and tobacco-processing all developed, basing their

increasing prosperity upon the raw materials of the British Empire. Many

Scots even made careers in war itself, enlisting in Scottish regiments

formed to fight Britain's battles wherever they might occur.

Few Scots therefore - except for the

Jacobites - were feeling any sense of grievance as the eighteenth century

proceeded. The intellectuals, lawyers and financiers of Edinburgh were

enjoying that city's Golden Age; in Glasgow and the Clyde area, merchants,

mill owners and ironmasters found little to complain about, and landowners

saw their income from rentals rising. Britain was, in truth, an enormous

success.

So at least it must have appeared to the

small proportion of the population which made, or helped to make, the

nation's decisions. In all Scotland only some 4-5000 people had the right

to vote. In most counties there were only around thirty or so voters, and

in the burghs, the Town Councils, themselves the creatures of the Merchant

and Craft Guilds, chose the MPs. This small group of the socially powerful

and economically dominant, were well pleased with their lot until things

began to go wrong.

With the accession of George III in 1760

new political tensions arose over the king's methods and apparent

purposes. His policies, which eventually brought about the American

Revolution and the independence of Britain's thirteen American colonies by

1783, caused the gradual emergence of demands for political reforms; and

the example of the independent United States, founded on freedom and

equality for all its citizens, encouraged more and more people to support

these demands.

Still, these successes and these grievances

were all British in character. Between 1707 and the 1770s there was no

voice speaking distinctively for Scotland; and indeed few signs that

anything distinctively Scottish commanded any great interest or support,

apart from the church, established by law, and satisfied with its

privileged position.

Strangers to Scotland, and many Scots

themselves, often feel puzzled by the hero-worship which so many bestow

upon Robert Burns. The truth is that if Burns had never lived, Scotland

could hardly have avoided going the way of ancient English-speaking

kingdoms whose indentity is long lost, merged within a greater whole.

Scotland today would rank alongside Mercia or Northumbria or Wessex, of

interest as an antiquity, a curiosity or an affectation. If Scotland is

anything more in modern times, it is because Burns, speaking as and for

the ordinary man, stemmed the tide of history, flowing strongly in the

direction of absorption and integration. His work meant that a sense of

identity was preserved at a time when the politically active classes in

Scotland showed little interest in any such sense. Aristocracy is by its

nature international. It is ordinary people, involved with humbler local

community life, who have greater national awareness. These ordinary people

had no political power until more than a century had passed, but when in

due course these people for whom Burns spoke did gain the right to

political participation, Scotland was still there.

Burns's lowly status and bucolic innocence

have been greatly exaggerated, not least by himself, for what might be

termed reasons of publicity. He was educated, beyond the average of his

class and time, at an 'adventure' school, run by one Murdoch, as a

business venture in Ayr. With this degree of education, and as the son of

a tenant farmer, he had a modest measure of leisure, and an interest in

the written word. Men like Burns, educated to full literacy and to some

extent self employed, were the most receptive audience for the

political

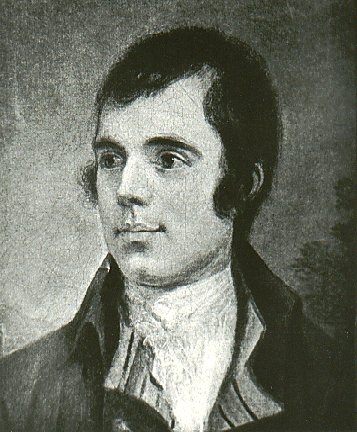

Robert Burns by Alexander

Nasmyth, 1787, 'detail' (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

writings which attended the American

Revolution, and, some ten years later, the French Revolution. Smiths and

tailors, weavers and cobblers, were to some extent able to determine their

own working hours, and could award themselves some time for study and

discussion. Members of these crafts were famous for generations for their

interest in radical politics, and around anvil and bench, loom and last,

many an impromptu debating society flourished; discussing public events,

recent publications and their own social condition. By the 1790s they

could have been discussing the triumph of democracy in America and the

principles of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity extended to all men by the

French revolutionaries after 1789.

In England support for reform in the 1770s

had led in time to the creation of the 'Friends of the People', mainly

well-intentioned and high-minded nobles, gentry and urban professional

men, whose friendship had in it elements of condescension. The Scottish 'Friends'

were more genuinely 'of the People'. When in 1792 and in 1793 the Scottish

'Friends' assembled under the exciting influence of events in France,

there were present representatives from active reform societies, mostly

craftsmen and members of professions, from most areas of the country.

Emerging as a leading figure in the Convention was the young Glasgow

lawyer, Thomas Muir, who had already gained a reputation by circulating

pamphlets and analysing their contents at meetings of 'Friends' in many

towns and villages. Unfortunately for Muir, the revolution in France had

become increasingly violent in character. Sympathy for the revolution

therefore ebbed; and the British government, genuinely afraid of

revolutionary infection, and happy to see the reform movement discredited

by bloodshed in France,

Thomas Muir of Huntershill.

(Sketch: David Martin)

now treated reform agitation as akin to

treason, and prepared to act against reformers. Muir was the first victim

of this policy; and, for circulating and encouraging the study of Tom

Paine's Rights of Man, he was adjudged guilty of sedition and sentenced to

be transported to Australia for fourteen years.

Once Britain was actually at war with

France, after 1793, reformers were, inevitably, extremists, meeting in

secret and frequently binding themselves by oaths - a practice always

alarming to governments. There thus developed the 'United Scotsmen' (the

title imitative of the already existing 'United Irishmen') organised in

local branches and district committees, meeting clandestinely, members

being known only by the name of the village, town or area branch which had

sent them as delegates. One focus for activity in Angus, Perthshire and

Fife, was Dundee, where several radical pamphlets were produced, an

exploit which caused the Rev. Thomas Fysshe Palmer to be transported for

seven years, and George Mealmaker, ringleader, organiser and author, for

fourteen years. Mealmaker earned the grudging admiration of the

authorities who were much surprised by the excellence of the writing of

which this ordinary weaver was capable.

These stern measures had their effect; and

though several conspiracy trials in Glasgow, and a major outbreak of

violence at Tranent, showed that discontent simmered below the surface,

the reformist cause undoubtedly weakened as the war dragged on. Burns

contributed some poems which attracted the disapproval of authority. He

had long ago written scathingly of the Hanoverians; and had attributed the

Union, which had made of Scotland 'England's province', to 'hireling

traitors . . . such a parcel of rogues in a nation.' He now wrote

encouragingly of the French Revolution, and contrasted the English

indifference to liberty with the support felt for the cause in Scotland,

in poems like 'Ode on General Washington's Birthday' and 'The Tree of

Liberty'. He made in his mind a connection between the present struggle

for liberty in France and the independence wars in Scottish history. His

feelings prompted him to find new words to an old marching tune, reputedly

played by Scots companies in the army of Joan of Arc. Using the tradition,

reported by Barbour, that Bruce had delivered an inspirational address to

his army at Bannockburn, Burns produced the poem, known by its opening

words, 'Scots wha hae'. By themselves these words are meaningless, and

those who do not read or do not wish to listen, have been quick to find

fault with the verses; but for others, the antiquity of the tune and the

sentiments of Burns's words combine to provide Scotland with what ought to

be her obvious and unchallenged National Anthem.

The interest of craftsmen in reform was not

however purely intellectual or sentimental; they had very real practical

grievances too. Between 1800 and 1808, for instance, the income of

handloom weavers had been halved, and their income continued to fall. In

1812 Glasgow weavers conducted a strike which lasted for nine weeks, an

event which prompted the government and local powers in the city, to

create a network of spies, informers and agents provocateurs to guard

against any recurrence of such disturbing events.

In the aftermath of the war which ended in

1815, conditions of many workers worsened, and in both England and

Scotland reformist agitation revived. In part men sought improvements in

their wages and conditions, but more and more they were coming to the

conclusion that only political power and friendly legislation could offer

them reasonable future prospects. The 'United Scotsmen', back in the

1790s, had demanded votes for all men, votes by ballot, annual General

Elections, and the payment of MPs; and these demands were the basis of the

political agitation which grew during the immediate post-war years. A 'National

Committee of Scottish Union Societies' had emerged during the 1812 strike.

The word 'society' has a long pedigree in Scottish political history,

Presbyterian extremists in the seventeenth century frequently being

referred to as 'society men'. The Unions were territorial, not

occupational; they were not trade unions, but area branches of the

national organisation. In fact the National Committee and its organisation

in the country gives every indication of being a revival of the 'United

Scotsmen'.

Events in England provided the spark which

set in motion the events of 1819-20. The 'Manchester Massacre' or 'Peterloo'

on 16 August 1819, provoked a storm of protests and demonstrations in

Scotland. In Paisley cavalry had to be called in to disperse 5000 'Radicals',

as the discontented were coming to be collectively called. A meeting in

Stirling attracted 2000 people; in Airdrie a demonstration was led by a

band playing 'Scots Wha Hae', for which action the entire band was

arrested, and in Dundee a prominent reformer leader, the 'Radical Laird',

Kinloch, was arrested for addressing a mass meeting on the Magdalen Green.

Irritated and alarmed by these and similar

events, the government now acted, using the tried and true methods

employed against the Covenanters in 1678, goading unknown numbers of an

underground organisation into open defiance, thus rendering themselves

open to identification and punishment. Thus, on 1 April 1820, Glasgow

awoke to find, widely displayed around the city, posters in the name of a 'Committee

. . . for . . . a Provisional Government', calling a general strike and

promising armed action in support of the reformers' demands. Word was

passed, without doubt by government agents, that supporters should march

to Carron works where weapons would be found; and armies, source unknown,

were reported to be mustering at Campsie and at Cathkin, under Kinloch and

Marshal MacDonald, the French soldier of exiled Highland parentage.

Encouraged at every step of the way by several mystery men bearing

instructions and advice, an armed band, led by Andrew Hardie of the Castle

Street Union, set off on 4 April to march from Glasgow to Carron pausing

to collect reinforcements under John Baird, weaver and ex-soldier, at

Condorrat. Hardie had twenty-five men when he contacted Baird in the early

hours of the 5th. Baird had only six men to add to the strength, but with

this little force, Hardie and Baird proceeded towards Carron, only to be

confronted by a cavalry force at Bonnymuir where the curiously well

informed authorities had ordered the Stirling military commander to meet

the rebels. Nineteen 'rebels' were conveyed prisoners to Stirling Castle.

Meanwhile radicals at Strathaven had been

instructed by messages from Glasgow, to march to Cathkin; and a force of

twenty-five men, including the sixty-three-year-old James Wilson, veteran

of the 'Friends of the People' and, probably, of the 'United Scotsmen',

marched as instructed. Warned of an ambush they returned home, but ten of

them were sought, identified and arrested, and held in custody in

Hamilton.

Rioters taken prisoner at Paisley were

conveyed to jail in Greenock, where the good citizens attacked the Port

Glasgow militia escorting the prisoners as they entered the town; attacked

them again as they withdrew, and finally attacked the jail and released

the prisoners.

So ended the 'Radical War'. On 30 August

James Wilson was hanged and beheaded in Glasgow, and on 8 September Hardie

and Baird were both hanged in Stirling. Other prisoners were transported

to Australia, and hopes for reform seemed dashed for long years to come.

The issue was kept alive in Parliament, where Lord Grey, once a member of

the 'Friends of the People', had introduced a proposal for reform more or

less annually, meeting as a rule nothing but ridicule. By 1830 however,

the memories of the French revolution and its massacres and executions

were fading, and the many absurdities of the unreformed political system

were inviting mounting criticism. Thus, in 1830, the General Election saw

the Whigs in power for the first time in fifty years; and Lord Grey, as

Prime Minister, at long last carried his Reform Bill into law in 1832.

The Reform Act extended the vote to only a

very small number of additional electors, but the frustrated lower orders

persevered in their attempts to secure political rights, drafting the

People's Charter - four of whose six points were the old demands of the 'United

Scotsmen' - and campaigning for ten years for its acceptance. Chartism was

strong in Scotland, and Scots showed their historical awareness by giving

to Chartist branches or clubs the names of Andrew Hardie, or John Baird,

or James Wilson or Thomas Muir, and many clubs took to themselves the name

of Robert Burns.

With the collapse in ridicule of the

Chartist attempt in 1848, men at last seemed to despair of finding a

solution to their material problems in gaining political power, and turned

instead to the formation of Trade Unions, legalised since 1824, whose

function was to negotiate with employers on wages and conditions,

abandoning the apparently impossible dream of democracy.

There was logic in the change of tactic.

The industrial developments of the preceding fifty years had been speeded

up as war created demand for munitions encouraging investment in

coal-mining and iron-founding. Industrial development was hardly possible

without improvements in transportation. Raw material had to reach the

factories, coal had to reach the foundries, and the finished products had

to reach distribution points en route to their various markets.

In the eighteenth century road construction

had been undertaken under the supervision of such experts as Thomas

Telford and John Macadam, but these roads - and the toll-financed Turnpike

Roads provided by local counties and private landowners - did not really

serve commercial purposes. For the transport of heavy and bulky cargoes

the most economical means of transport was by water, on ship or barge.

Thus the early expansion of heavy industry was assisted by the building of

canals - the Monkland Canal, linking the Lanarkshire coal and ironfields

with the wharves at Port Dundas in Glasgow; the Forth and Clyde Canal,

crossing Scotland from Grangemouth to Bowling, and the Union Canal which

connected industry in and around Edinburgh with the Forth and Clyde Canal

at Bainsford, in Falkirk. These canals were effective, but goods moved

very slowly. A faster method of distribution was found by adapting the

technique, long-used in collieries, of having loaded wagons run on fixed

rails from the point of production to the point of marketing. A railway of

this sort had run from the Ayrshire coal-fields to Troon, where coal was

shipped for Ireland, and similar wagon-ways existed in the Lothians. Along

such lines horses could draw heavy loads, or stationary steam engines

could, by rope or chain, draw wagons from point to point. With growing

ingenuity in steam engineering came the production of locomotive engines,

which themselves could run on the track provided, drawing trains of wagons

behind them.

The Union Canal at

Edinburgh. (Photo: Gordon Wright).

The pioneering work in steam engineering of

James Watt was thus applied by George Stephenson; and in a remarkably

short time railways were in operation, or under construction, throughout

Britain. In Scotland, Edinburgh and Glasgow were linked by rail by 1842,

and spur lines ran from the cities to the smaller towns in their areas.

Railway connections with the south were established with the foundation in

1845 of the Caledonian Railway which linked Glasgow with the North Western

Railway at Carlisle, and thence to London. In 1846 a similar plan linked

the North British Railway, based in Edinburgh, with the English rail-head

at Newcastle; while in 1850 a third link was provided when the Midland

Railway, of Derby, connected with the Glasgow and South Western Railway at

Dumfries.

Industrial costs were dramatically lowered

and profits accordingly soared. Production of coal and iron (and steel)

was in greatly increased demand and new jobs at all levels were provided -

labourers to lay the tracks and civil engineers to plan them; mechanical

engineers to design locomotives; labourers to smelt the iron-ore; platers

and riveters to build them; drivers and firemen to crew the engines, and

signalmen and surfacemen to see to the safe scheduled running of the

trains.

The social consequences were also

spectacular. The railway network integrated the country as never before,

as travel was now possible for people with little leisure and no private

transport. For the fortunate, railways made it possible to live at a

distance from the place of employment, and suburbs arose around the

cities, providing more work for architects, masons, builders, carpenters

and slaters, plumbers and painters.

The outcome was a second, and vaster,

Industrial Revolution. Soon the expansion of the railways was paralleled

by the provision of steamships, and the firths of Clyde, Forth and Tay

became highways of trade. Forth and Tay had long experience of this kind

of thing, but for the Clyde it was something new. Glasgow's development

had been retarded because the Clyde was not navigable for anything but

small boats above Dumbarton. Glasgow merchants, even in the great days of

the tobacco trade, had had to unload cargoes some twenty miles away, and,

in order to avoid paying fees for the use of Greenock's harbours, these

merchants had bought land and built their own port - Port Glasgow. In 1756

the Clyde just above Dumbarton was little more than a swamp, with a

central channel of a mere fifteen inches in depth (less than half a metre).

By engineering, begun by John Golborne in 1768, Glasgow's leading citizens

began to deepen the channel, commissioning the building of walls and

jetties, blasting heavy clay from the river bed, and employing a fleet of

dredgers, until by 1886 they had a channel of some 20 feet deep (around 6

metres) and some 300 feet broad (100 metres). As has been said, 'Glasgow

made the Clyde, and the Clyde made Glasgow.'

With a river now rendered navigable,

Glasgow became one of the world's greatest centres for seaborne trade, and

for the shipbuilding and marine engineering industries which provided the

vessels. From the building at Port Glasgow in 1811 of Henry Bell's Comet,

steamers provided the main means of access from Glasgow to all points on

the Firth of Clyde, to the Hebrides, to Ireland and England, and

eventually to every continent in the world. The cousins, Robert and David

Napier, pioneered in ship-building and engineering, and many who learned

their skills in Napier's yards became major figures in the world of

shipping themselves, as builders, engineers or as operators of fleets of

steamers. These steamers carried locomotives from Springburn and St Rollox

to India, Africa and South America; metalware from Glasgow itself, from

Lanarkshire and Falkirk; fabrics from Paisley and the Vale of Leven to all

corners of the globe. 'Clyde-built' was taken to be an indicator of

excellence, and Glasgow especially and central Scotland as a whole, became

one of the busiest and most thriving corners of the 'workshop of the world'

which Victorian Britain had become.

For all this success a heavy price was paid

by the people whose labour made it all happen. Work in 'heavy' industries

and in textile production was unhealthy and often dangerous for the men,

women and children who worked long hours for miserably low wages. Even

away from their work the workers could not escape from the consequences of

industrialisation. Their homes, often built by the employers conveniently

close to the place of employment, were all too commonly slums;

over-crowded, insanitary and polluted by smoke and fumes from factories

and railway yards. Employers, most of them of humble social origins

themselves, were generally harsh and ruthless, feeling no obligation

The Comet near Port Glasgow.

(Photo: Glasgow Herald)

tended towards those less successful than

themselves. Most saw their success as proof of their own superior

qualities, and found justification in economic and religious theories for

their readiness to accept the gross extremes of wealth and poverty. It is

a major tragedy that when Scotland did once prosper, all but a handful of

her people derived no benefit from that prosperity.

Such social responsibility as there was,

had come from the church. For many generations education and relief of

poverty had been administered by the church. This system had worked

acceptably while most of the people were Presbyterian churchgoers; but by

the mid-nineteenth century the church had lost most of its contacts with

industrial workers living in the worst city areas and tended increasingly

to be an organisation concerned wholly with 'respectable' people. Also,

immigrants from Ireland, brought over by employers to work in mines, on

railway construction and other heavy and unattractive jobs, had brought

with them their Catholic faith. Thus, whereas in 1755 there were no

Catholics in Ayrshire, 2 in Lanarkshire, 3 in Renfrewshire, none in

Dumbartonshire and 8 in Stirlingshire, by the late 1800s these

industrialised counties had a large and growing Catholic population. To

make the Church of Scotland responsible for the social care of these new

communities was hardly realistic.

To make matters worse, in 1843, after long

years of controversy over the right of the state to interfere in church

affairs, a substantial proportion of the ministers, elders and members

left the Church of Scotland and founded the Free Church. This 'Disruption'

had far-reaching consequences. The Free Church set itself the task of

providing a second network of churches, manses and schools, duplicating

those of the established 'Auld Kirk'. The latter, weakened by the loss of

almost half its members, was no longer able to meet its traditional

responsibilities, and thus the provision of poor relief and of education

at parish level became a matter for the state or the local authorities in

counties and burghs.

Parliament had acted at various times

during the century to remedy some of the worst consequences of

industrialisation. A succession of Factory Acts had regulated hours and

age of workers, and the Coal Mines Acts had prohibited underground working

by women and children. But the issues of politics were still dictated by

the interest and opinions of a minority. Despite the extension of voting

rights in 1832, 1867 and 1884, only 58 per cent of adult males had the

vote, and women not at all. Political battles were fought over the issues

which interested the comparatively prosperous, comparatively secure

sections of the community.

Unemployment was not an issue because few

voters were unemployed. Housing conditions were not an issue because

voters were, in general, comfortably housed. Poverty could be blamed on

laziness and drink, because voters were seldom poor. Politics, as the

century neared its end, were dominated by Irish Home Rule, the recurring

massacres of Armenians and Bulgarians by Turks, and the proposal to

abandon Free Trade and reintroduce protective tariffs.

For the problems of the industrial workers

and the poor to secure attention a change in the whole basis of politics

and parties was required. |