|

STEWART, a surname

derived from the high office of steward of the royal household, and

distinguished as being that of a race of Scottish kings which occupied

the throne of Scotland for upwards of three hundred, and that of England

for more than one hundred years. The name is sometimes written Steuart,

and by the later royal family of Scotland, Stuart. As various families

throughout Scotland, as well as in England and Ireland, bear this

surname, some of the principal branches having diverged from the main

line at a period antecedent to its becoming royal, it may be assumed

that those who retain the original spelling belong to some one or other

of these branches, that the families who adopt the spelling of Steuart

are offshoots, generally illegitimate, of the royal house previously to

Queen Mary, and that the form of Stuart, which was only assumed, for the

first time, when that ill-fated princess went to France, is exclusively

that of the royal blood. In the death-warrant of Charles I. the name is

spelled Steuart.

The first of the family

of Stewart is said by Pinkerton to have been a Norman baron named Alan,

who obtained from William the Conqueror the barony of Oswestry in

Shropshire. He was the son of Flaald, and the father of three sons,

William, Walter and Simon. It is from the second that the royal family

of Scotland descend.

The eldest son, William,

was the progenitor of a race of earls of Arundel, whose title, being

territorial, and lands, ultimately went by an heiress into the family of

the duke of Norfolk. The two younger sons, Walter and Simon, came to

Scotland. Walter was by David I. appointed dapifer, that is, meat-bearer

or steward of the royal household; sometimes called seneschallus. Simon

was the ancestor of the Boyds, his son, Robert, having been called Boidh,

from his yellow hair.

The duties of

high-steward comprised the management of the royal household, as well as

the collection of the national revenue and the command of the king’s

armies, and from the office Walter’s descendants took the name of

Stewart.

From David I. (1124-1153)

Walter obtained the lands of Renfrew, Paisley, Pollock, Cathcart, and

others in that district, and in 1157, King Malcolm IV. granted a charter

of confirmation of the same. In 1160, he founded the abbey of Paisley,

the monks of which, of the Cluniac order of Reformed Benedictines, were

brought from the priory of Wenlock in Shropshire. Walter died in 1177,

and was interred in the monastery at Paisley, the burying-place of the

Stewarts before their accession to the throne, Renfrew being their usual

residence.

Walter’s son and

successor, Alan, died in 1204, leaving a son, Walter, who was appointed

by Alexander II. justiciary of Scotland, in addition to his hereditary

office of high-steward. He died in 1246, leaving four sons and three

daughters. Walter, the third son, was earl of Menteith. The eldest son,

Alexander, was, in 1255, one of the councilors of Alexander III., then

under age, and one of the regents of Scotland. He married Jean, daughter

and heiress of James, lord of Bute, grandson of Somerled, and, in her

right, he seized both the Isle of Bute and that of Arran. The complaints

made to the Norwegian court by Ruari or Roderick of Bute, and the other

islanders, of the aggressions of the Scots, led to Haco’s celebrated

expedition, and the battle of Largs, 2d October 1263, in which the

high-steward commanded the right wing of the Scots army, and the

Norwegians were signally defeated. In 1265 the whole of the western

isles were ceded by treaty to Scotland.

Alexander had two sons,

James, his successor, and John, known as that Sir John Stewart of

Bonkill, who fell at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Under Sir John

Stewart, in this battle, were the men of Bute, known at that time by the

name of the Lord-high-steward’s Brandanes, and they were almost wholly

slain with their valiant leader. Wyntoun says:

“Thare Jhon Stwart a-pon

fute,

Wyth hym the Brandanys thare of Bute.”

Sir John Stewart had

seven sons. 1. Sir Alexander, ancestor of the Stewarts, earls of Angus.

2. Sir Alan of Dreghorn, of the earls and dukes of Lennox, of the name

of Stewart. 3. Sir Walter, of the earls of Galloway. 4. Sir James, of

the earls of Athol, Buchan, and Traquair (see these titles), and the

Lords Lorn and Innermeath. 5. Sir John, killed at Halidonhill in 1333.

6. Sir Hugh, who fought in Ireland under Edward Bruce. 7. Sir Robert of

Daldowie.

James, the elder son of

Alexander, succeeded as fifth high-steward in 1283. On the death of

Alexander III. in 1286, he was one of the six magnates of Scotland

chosen to act as regents of the kingdom. In the subsequent contest for

the crown, he was one of the auditors on the part of Robert de Brus, but

fought bravely under Sir William Wallace in his memorable attempt to

retrieve the national independence. He submitted to Edward I., 9th July

1297. In 1302, with other six ambassadors, he was sent to solicit the

aid of the French king against Edward, to whom he was compelled to swear

fealty at Lanercost, October 23d, 1306. To render his oath if possible

secure, it was taken upon the two crosses of Scotland most esteemed for

their sanctity, on the consecrated hose, the holy gospels, and certain

relics of saints. He also agreed to submit to instant excommunication if

he should break his allegiance to Edward. Convinced that his faith was

to his country and not to a usurper, in spite of all, he once more took

part in the patriotic cause, and died in the service of Bruce, in 1309.

His son, Walter, the

sixth high-steward, when only twenty-one years of age, commanded with

Douglas the left wing of the Scots army at the battle of Bannockburn.

Soon after, on the liberation of the wife and daughter of Bruce from

their long captivity in England, the high-steward was sent to receive

them on the borders, and conduct them to the Scottish court. In the

following year, King Robert bestowed his daughter, the Princess Marjory,

in marriage upon him, and from them the royal house of Stuart and the

present dynasty of Great Britain are descended. The lordship of Largs,

on the forfeiture of John Baliol, had been conferred by Bruce on the

high-steward, and with his daughter he got in dowry an extensive

endowment of lands, particularly the barony of Bathgate, Linlithgowshire.

The princess died in 1316. According to a local but unauthenticated

tradition, she was thrown from her horse and killed at a place called

the Knock, near Renfrew, leaving a son, afterwards Robert II.

During the absence in

Ireland of his illustrious father-in-law, to the high-steward and Sir

James Douglas, Bruce confided the government of the kingdom, and by them

the borders were gallantly defended against all the inroads of the

English. On the capture of Berwick from the English in 1318, he got the

command of that town, which, on 24th July 1319, was laid siege to by

Edward II. The English brought formidable engines against the walls, and

on these being destroyed by the garrison, the steward rushed from the

town, and by a sudden onset beat off the enemy. In 1322, with Douglas

and Randolph, he made an attempt to surprise the English king at Biland

abbey, near Melton, Yorkshire. Edward, however, escaped, though with the

utmost difficulty, to York. Walter pursued him with five hundred horse,

and in the spirit of chivalry, waited at the gates till the evening for

the enemy to issue forth and renew the combat. He died 9th April 1326,

at the castle of Bathgate, one of his chief residences, which was

curiously situated in the centre of a bog. At the time of his death he

was only thirty-three years of age.

His son, Robert, seventh

lord-high-steward, had been declared heir presumptive to the throne in

1318, but the birth of a son to Bruce in 1326 interrupted his prospects

for a time. From his grandfather he received large possessions of land

in Kintyre. During the long and disastrous reign of David II. the

steward acted a patriotic part in defence of the kingdom. At the fatal

fight of Halidon-hill in 1333, when little more than seventeen years of

age, he commanded the second division of the Scottish army, under the

inspection of his father’s brother, Sir James Stewart of Durrisdeer. A

short time after, when Scotland was nearly overrun by Edward III., he

was forfeited by that monarch, and his office of high-steward given to

the English earl of Arundel, who pretended a right to it, in

consideration of his descent from the elder brother of Walter, the first

steward of the family. Robert Stewart, as he was usually called, “was,”

says Fordun, “a comely youth, tall and robust, modest, liberal, gay, and

courteous, and, for the innate sweetness of his disposition, generally

beloved by all true-hearted Scotsmen.” In 1334, after the temporary

success of Edward Baliol, the young steward was forced to conceal

himself for a time in Bute. Escaping thence the following year, he

recovered his own castle of Dunoon, in Cowal, which had been taken by

Baliol. He next reduced the island of Bute, and caused the people of

Renfrewshire and Ayrshire to acknowledge David II. On the death, in

1338, of the regent, Sir Andrew Moray of Bothwell, the command of the

Scots army devolved upon the steward; and, shortly afterwards, by the

treachery of its governor Bulloch, an ecclesiastic whom Baliol had

appointed chamberlain of Scotland, he obtained possession of the castle

of Cupar in Fife, which the late regent had in vain attempted to take by

force. By his exertions, the English were driven from the country, and

on the return of David II., then in his eighteenth year, from his nine

years’ exile in France, in June 1341, he was enabled to restore to him

his kingdom free, and once more established in peace and order. In 1346,

when David II. was defeated and taken prisoner at the battle of Durham,

the remains of the Scots army were conducted home in safety by the earl

of March and the steward of Scotland. The latter, during the

imprisonment of the king, was again appointed regent. In 1357, he

effected the liberation of the king, his own eldest son being one of the

hostages sent to England in his stead. King David, the following year,

conferred on him the earldom of Strathern. The king afterwards entered

into a disgraceful plot with the English monarch, to have the kingdom of

Scotland settled on Prince Lionel, duke of Clarence, a son of the

latter. On proposing this to the Scots parliament in 1363, the steward

assembled his adherents, to enforce his right of succession, which had

been confirmed by a former parliament. The king, on his part, marched

with an army against the partisans of the steward, and soon awed them

into submission. David, however, was compelled to respect the law of

succession as established by King Robert the Bruce; and he conferred the

earldom of Carrick, formerly belonging to that monarch, upon the eldest

son of the steward, afterwards Robert III. On David’s marriage with the

daughter of Sir John Logie in 1368, the steward and his adherents were

thrown into prison. On the death of David, without issue, February 22d

1371, the steward, who was at that time fifty-five years of age,

succeeded to the crown as Robert II., being the first of the family of

Stewart who ascended the throne of Scotland.

The direct male line of

the elder branch of the Stewarts terminated with James V., and at the

accession of James VI., whose descent on his father’s side was through

the earl of Lennox, the head of the second branch, there did not exist a

male offset of the family which had sprung from an individual later than

Robert II. Widely as some branches of the Stewarts have spread, and

numerous as are the families of this name, there is not a lineal male

representative of any of the crowned heads of the race, Henry, Cardinal

York, who died in 1804, being the last. The crown which came into the

Stewart family through a female seems destined ever to be transmitted

through a female. From the princess Elizabeth, daughter of James VI.,

descended, through her daughter, Sophia, electress of Hanover, the

present line of British monarchs. The nearest heir of the royal house of

Stuart by direct descent is Francis V., grand-duke of Modena, born June

1, 1819 (accession, 1846, ceased to govern, 1859), his mother having

been Mary Beatrice, of the royal house of Sardinia. The princess

Henrietta, younger daughter of Charles I. of Great Britain, married the

duke of Orleans, and had 2 daughters, one of whom married the king of

Sardinia, whose elder twin daughter married the duke of Modena.

The male representation

or chiefship of the family is claimed by the earl of Galloway; also, by

the Stewarts of Castlemilk as descended from a junior branch of Durnley

and Lennox.

_____

STEWART, the name of one

of the Scottish clans not originally of Celtic origin. The first and

principal seat of the Stewarts was in Renfrewshire, but branches of them

penetrated into the western Highlands and Perthshire, and acquiring

territories there, became founders of distinct families of the same

name. Of these the principal were the Stewarts of Lorn, the Stewarts of

Athole, and the Stewarts of Balquhidder, from one or other of which all

the rest have been derived. The Stewarts of Lorn were descended from a

natural son of John Stewart, the last lord of Lorn, who, with the

assistance of the M’Larens, retained forcible possession of part of his

father’s estates. From this family sprang the Stewarts of Appin, who,

with the Athole branches, were considered in the Highlands as forming

the clan Stewart. The badge of the original Stewarts was the oak, and of

the royal Stuarts, the thistle.

The district of Appin

forms the north-west corner of Argyleshire. In the Ettrick Shepherd’s

well-known ballad of ‘The Stewarts of Appin,’ he thus alludes to it:

“I sing of a

land that was famous of yore,

The land of green Appin, the ward of the flood,

Where every grey cairn that broods over the shore,

Marks graves of the royal, the valiant, or good;

The land where the strains of grey Ossian were framed, --

The land of fair Selma, and reign of Fingal, --

And late of a race, that with tears must be named,

The noble Clan Stewart, the bravest of all,

Oh-hon a Rei! And the Stewarts of Appin!

The gallant, devoted old Stewarts of Appin!

Their glory is o’er,

For the clan is no more,

And the Sassenach sings

on the hills of Green Appin!”

In the end of the fifteenth century, the Stewarts of Appin were vassals

of the earl of Argyle in his lordship of Lorn. In 1493 the name of the

chief was Dougal Stewart. He was the natural son of John Stewart, the

last lord of Lorn, and Isabella, eldest daughter of the first earl of

Argyle. The assassination of Campbell of Calder, guardian of the young

earl of Argyle, in February 1592, caused a feud between the Stewarts of

Appin and the Campbells, the effects of which were long felt. During the

civil wars, the Stewarts of Appin ranged themselves under the banners of

Montrose, and at the battle of Inverlochy, 2d February 1645, rendered

that chivalrous nobleman good service. They and the cause which they

upheld were opposed by the Campbells, who possessed the north side of

the same parish, a small rivulet, called Con Ruagh, or red bog, from the

rough swamp through which it ran, being the dividing line of their

lands.

The Stewarts of Appin

under their chief, Robert Stewart, engaged in the rebellion of 1715,

when they brought 400 men into the field. They were also “out” in 1745,

under Stewart of Ardshiel, 300 strong. Some lands in Appin were

forfeited on the latter occasion, but were afterwards restored. The

principal family is extinct, and their estate has passed to others,

chiefly to a family of the name of Downie. There are still, however,

many branches of this tribe remaining in Appin. The chief cadets are the

families of Ardshiel, Invernahyle, Auchnacrone, Fasnacleich, and

Balachulish.

Between the Stewarts of

Invernahyle and the Campbells of Dunstaffnage, there existed a bitter

feud, and about the beginning of the sixteenth century, the former

family were all cut off but one child, the infant son of Stewart of

Invernahyle, by the chief of Dunstaffnage, called Cailein Uaine, or

Green Colin. The boy’s nurse fled with him to Ardnamurchan, where her

husband, the blacksmith of the district, resided. The latter brought him

up to his own trade, and at sixteen years of age he could wield two

forehammers at once. One in each hand, on the anvil, which acquired for

him the name of Domhnull nan ord, or Donald of the hammers. Having made

a two-edged sword for him, his foster-father, on presenting it, told him

of his birth and lineage, and of the event which was the cause of his

being brought to Ardnamurchan. Burning with a desire for vengeance,

Donald set off with twelve of his companions, and at a smithy at Corpach

in Lochaber, he forged a two-edged sword for each of them. He then

proceeded direct Dunstaffnage, where he slew Green Colin and fifteen of

his retainers. Having recovered his inheritance, he ever after proved

himself “the unconquered foe of the Campbell.” The chief of the Stewarts

of Appin being, at the time, a minor, Donald of the hammers was

appointed tutor of the clan. He commanded the Stewarts of Appin at the

battle of Pinkie in 1547, and on their return homewards from that

disastrous field, in a famishing condition, they found in a house at the

church of Port of Menteith, some fowls roasting for a marriage party.

These they took from the spit, and greedily devoured. They then

proceeded on their way. The earl of Menteith, one of the marriage

guests, on being apprised of the circumstance, pursued them, and came up

with them at a place called Tobernareal. To a taunt from one of his

attendants, one of the Stewarts replied by an arrow through the heart.

In the conflict that ensued, the earl fell by the ponderous arm of

Donald of the hammers, and nearly all his followers were killed. The

History of Donald of the Hammers, written by Sir Walter Scott, will be

found in the fifth edition of Captain Burt’s Letters.

_____

The Stewarts of Athole

consist almost entirely of the descendants, by his five illegitimate

sons, of Sir Alexander Stewart, earl of Buchan, called, from his

ferocity, ‘The wolf of Badenoch,’ the fourth son of Robert II., by his

first wife, Elizabeth More. One of his natural sons, Duncan Stewart,

whose disposition was as ferocious as his father’s, at the head of a

vast number of wild Catherans, armed only with the sword and target,

descended from the range of hills which divides the counties of Aberdeen

and Forfar, and began to devastate the country and murder the

inhabitants. Sir Walter Ogilvy, sheriff of Angus, Sir Patrick Gray, and

Sir David Lindsay of Glenesk, immediately collected a force to repel

them, and a desperate conflict took place at Gasklune, near the water of

Isla, in which the former were overpowered, and the greater part of them

slain.

James Stewart, another of

the Wolf of Badenoch’s natural sons, was the ancestor of the family of

Stewart of Garth, from which proceed almost all the other Athole

Stewarts. A battle is traditionally said to have been fought in Glenlyon

between the M’Ivers, who claimed it as their territory, and Stewart of

Garth, commonly called ‘the fierce wolf,’ the brother of the earl of

Buchan, which terminated in the utter defeat of the M’Ivers, and their

expulsion from the district. The Garth family became extinct in the

direct line, by the death of General David Stewart, author of a History

of the Highlands, a memoir of whom is given below. The possessions of

the Athole Stewarts lay mainly on the north side of Loch Tay.

The Balquhidder Stewarts

derive their origin fro illegitimate branches of the Albany family.

_____

The Stewarts of

Grandtully, Perthshire, are descended from James Stewart of Pierston and

Warwickhill, Ayrshire, who fell at Dupplin in 1332, 4th son of Sir James

Stewart of Bonkill, son of Alexander 4th lord-high-steward of Scotland.

Of this family was Thomas Stewart of Balcaskie, Fifeshire, a lord of

session, created a baronet of Nova Scotia, June 2, 1683.

His son, Sir George

Stewart, 2d bart., inherited Grandtully, and died without issue. His

brother, Sir John Stewart, 3d bart., an officer of rank in the army,

married, 1st, Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of Sir James Mackenzie of

Royston, and had by her an only surviving son, Sir John, 4th baronet;

2dly, Lady Jane Douglas, only daughter of James, marquis of Douglas, and

his son, by her, Archibald Stewart, after a protracted litigation,

succeeded to the immense estates of his uncle, the last duke of Douglas,

and assuming that name, was created a peer of the United Kingdom by the

title of Baron Douglas. Title extinct on the death of the 4th Lord

Douglas in 1857. Sir John Stewart married, 3dly, Helen, a daughter of

the 4th Lord Elibank, without issue. He died in 1764.

His son, Sir John, 4th

bart., died in 1797.

Sir John’s eldest son,

Sir George, 5th bart., married Catherine, eldest daughter of John

Drummond, Esq. of Logie Almond, and died in 1827, leaving 5 sons and 2

daughters.

The eldest son, Sir John,

6th bart., died without issue, May 20, 1838.

His brother, Sir William

Drummond Stewart, born Dec. 25, 1795, succeeded as 7th baronet. He

served in the 15th Hussars in the campaign of 1815, and is a knight of

the order of Christ of Italy and Portugal; married in 1830; issue, a

son, William George, captain 93d Highlanders, born in Feb. 1831.

_____

The family of Stewart,

now Shaw Stewart of Blackhall and Greenock, Renfrewshire, is descended

from Sir John Stewart, one of the natural sons of Robert III. From his

father Sir John received three charters of the lands of Ardgowan,

Blackhall, and Auchingoun, all in Renfrewshire, dated 1390, 1396, and

1404. Sir Archibald Stewart of Blackhall, the fifth from Sir John, was

one of the commissioners to parliament for the shire of Renfrew, in the

reign of Charles I., by whom he was made one of his privy council, and

knighted. He was also of the privy council of Charles II., when in

Scotland in 1650. He died in 1658. His grandson, Sir Archibald Stewart

of Blackhall, was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, 27th March 1667. He

had three sons and a daughter. His youngest son, Walter Stewart of

Stewarthill, which estate he purchased in 1719, was solicitor-general

for Scotland.

The eldest son, Sir John

Stewart of Blackhall, the second baronet of the family, was one of the

commissioners for Renfrewshire to the union parliament. His son, Sir

Michael Stewart, the third baronet, was admitted advocate in 1735. He

married Helen, daughter of Sir John Houston of Houston, by his wife,

Margaret Shaw, only daughter of Sir John Shaw of Greenock, and of Dame

Eleanor Nicolson, daughter of Sir Thomas Nicolson of Carnock. With two

daughters, Sir Michael had three sons. 1. Sir John, who, on the death of

his grand-uncle, Sir John Shaw of Greenock, in 1752, without male issue,

inherited the entailed estate of Greenock, consisting of the conjoined

baronies of Easter and Wester Greenock, as also Finnart. 2. Houston,

who, on the death of Sir John Houston, succeeded to the entailed estate

of Carnock, and assumed the additional surname of Nicolson. His only

son, Michael, succeeded as fifth baronet. 3. Archibald, who purchased an

estate in Tobago in 1770, and was killed in 1779, in repulsing some

American privateers who had landed and burnt two plantations on that

island.

The eldest son, Sir John

Shaw Stewart of Greenock and Blackhall, became fourth baronet on his

father’s death, 20th October 1796. He was M.P. for Renfrewshire, and

dying without issue, in August 1812, was succeeded by his nephew, Sir

Michael Shaw Stewart, fifth baronet. The latter was lord-lieutenant of

the county of Renfrew, and died in August 1825. He married his cousin,

Catherine, youngest daughter of Sir William Maxwell, baronet, of

Springkell, and had six sons and three daughters. His third son,

Rear-admiral Sir Houston Stewart, K.C.B., born at Springkell in 1791,

was educated at Chiswick. He entered the navy in 1805, and served under

the earl of Dundonald, then Lord Cochrane. He was at the siege of

Flushing, and commanded the Benbow at the bombardment of St. Jean d’Acre.

In 1846 he held the temporary command at Woolwich for a few months. In

November of that year he was appointed comptroller-general of the coast

guard, an office which he held till February 1850, when he became a lord

of the admiralty. In 1851 he attained the rank of rear-admiral, and in

February 1852 was elected M.P. for Greenwich, but only retained his

place in parliament till July of that year, and in the following

December he ceased to be a lord of the admiralty. In 1855 he was created

a knight commander of the Bath, for his services as second in command of

the naval forces off Sebastopol in that year. In 1858 he was appointed a

vice-admiral of the white. He married a daughter of Sir William Miller

of Glenlee, bart., issue 4 sons.

The eldest son, Sir

Michael Shaw Stewart, 6th baronet, was M.P., first for Lanarkshire and

afterwards for Renfrewshire, and died Dec. 19, 1836. By his wife, Eliza

Mary, only child of Robert Farquhar, Esq. of Newark, Renfrewshire, he

had 6 children, three of whom were daughters.

His eldest son, Sir

Michael Robert Shaw Stewart, 7th bart., born in 1826, is 17th in direct

male descent from the founder of the family. Educated at Christ Church,

Oxford, and formerly lieutenant 2d Life-guards; he married, in 1852,

Lady Octavia Grosvenor, daughter of 2d marquis of Westminster; issue, 2

sons and 2 daughters; is a magistrate and deputy-lieutenant of

Renfrewshire, and was M.P. for that county in 1855. His elder son,

Michael Hugh, was born in 1854. Sir Michael’s next brother, John

Archibald, inherited Carnock.

_____

The Stewarts of Drumin,

Banffshire, now of Belladrum, Inverness-shire, trace their descent from

Sir Walter Stewart of Strathaven, knighted for his services at the

battle of Harlaw in 1411, one of the illegitimate sons of the Wolf of

Badenoch, and consequently of royal blood. The representative of the

family, John Stewart, Esq. of Belladrum, born 29th May 1784, was M.P.

for Beverley in the last parliament of George IV. He died in 1860. He

had 2 sons and 2 daughters. Sons: 1. Charles, born in 1817, appointed in

1839 to the East India Company’s civil service. 2. John Henry Fraser,

born in 1821, formerly an officer in the army.

_____

The Stewarts of Binnie,

Linlithgowshire, descend from Sir Robert Stewart of Tarbolton and

Cruickston, 2d son of Walter, 3d high-steward and justiciary of

Scotland, in the reign of Alexander II. The lands of Binnie were

purchased by Robert Stewart, advocate, the 12th of the family.

Previously to his time the family designations were, of Torbane and

Raiss, Halrig, and Shawood. The representative of the family, John

Stewart of Binnie, born March 4, 1776, at one period a captain in the

East India Company’s maritime service, succeeded his elder brother,

Robert Stewart, in 1802.

_____

The Stewarts of St. Fort,

Fifeshire, representatives of the old family of Stewart of Urrard,

Perthshire, are descended from John, another natural son of the Wolf of

Badenoch. John Stewart of Urrard, the fifth of the family, had, besides

James his heir, another son, who died in childhood, of fright during the

battle of Killiecrankie, which was fought beside the mansion-house of

Urrard in 1689. The elder son, James Stewart of Urrard, had, with other

children, a daughter, Jean, called Minay n’m lean, the wife of Niel

M’Glashan of Clune. She is said to have acted a distinguished part in

Stirling castle, after the battle of Sheriffmuir in 1715. Robert Stewart

of this family, born in 1746, was a captain in the East India Company’s

service, on the staff of General Clavering. On his return to Scotland he

purchased the estates of Castle Stewart in Wigtownshire, and St. Fort in

Fifeshire, the former of which was afterwards sold. By his wife, Ann

Stewart, daughter of Henry Balfour of Dinbory, he had, with two

daughters, three sons. 1. Archibald Campbell, who succeeded him, and

died unmarried. 2. Henry, who succeeded his brother. 3. William, an

officer in the Coldstream guards, who assumed the surname of Balfour, in

addition to Stewart, in conformity to the will of his maternal uncle,

Lieutenant-general Nisbet Balfour.

Henry Stewart of St.

Fort, born in 1796, married, in 1837, Jane, daughter of James Fraser,

Esq. of Calderskell, issue 2 sons. Robert Balfour, the elder, was born

in 1838.

_____

The Stewarts of Physgill

and Glenturk, Wigtownshire, descend from John Stewart, parson of

Kirkmahoe, 2d son of Sir Alexander Stewart of Garlies, who died in 1590.

Agnes, only child of

Lieutenant Robert Stewart, R.N., and grand-daughter of John Stewart of

Physgill, succeeded to both the estates of Physgill and Glenturk, the

latter in right of her mother, Agnes Stewart, heiress of Robert Stewart

of Glenturk. IN 1740 she married John Hathorn of Over Airies, in the

same county, and had a son, Robert Hathorn Stewart, who succeeded his

mother. This gentleman married, in 1794, Isabella, only daughter of Sir

Stair Agnew, of Lochnaw, bart.; issue 2 sons and 2 daughters. He died

Nov. 7, 1818.

His elder son, Stair

Hathorn Stewart, Esq. of Physgill, born in 1796, was educated at Oxford;

a magistrate and a deputy-lieutenant and convener of the county of

Wigtown. He married, 1st, in 1820, Margaret, only daughter of James

Johnston of Straiton, issue, a son and a daughter; 2dly, in 1826, Helen,

youngest daughter of the Right Hon. Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster, bart.,

issue, 2 sons and 2 daughters; 3dly, in 1846, Jane Rothes, daughter of

John Maitland, Esq. of Freugh, Wigtownshire. His eldest son, Robert

Hathorn Johnston, born in 1824, an officer 93d Highlanders, succeeded,

in 1841, on the death of his uncle, James Johnston, Esq. of Straiton, to

his entailed estates in Mid Lothian and West Lothian, and in consequence

assumed the additional name of Johnston. He married, 1st, in 1851,

Ellen, daughter of Archibald Douglas, Esq. of Glenfinnart, Argyleshire;

2dly, in 1856, Anne, daughter of Sir William Maxwell, of Monreith,

baronet.

_____

The Stewarts of Coll and

Knockrioch, Argyleshire, were formerly designed of Benmore, Perthshire.

The present representative, John Lorne Stewart, Esq., born in 1800, is

the eldest son of Duncan Stewart, Esq. of Glenbuckie, by Margaret,

daughter of Duncan Stewart, Esq. of Ardsheal. He married, in 1831, Mary,

daughter of Archibald Campbell, Esq. with issue. Is a magistrate for

Perthshire, and a deputy-lieutenant of Argyleshire. His son and heir,

Duncan, born in 1834, married, in 1858, Ferooza Margaret, daughter of

Sir John M’Neill, G.C.B.

_____

In the stewartry of

Kirkcudbright are the families of Stewart of Shambelly, and Stewart of

Cairnsmore.

William Stewart, Esq. of

Shambelly, born in 1815, eldest son of William Stewart, Esq. of

Shambelly, by Bertha, daughter of Charles Donaldson, Esq. of Broughton,

succeeded in 1844. In 1841 he was appointed a deputy-lieutenant of the

stewartry, and, in 1846, major in the Galloway militia, but resigned in

1854. In 1845 he married Katherine, daughter of John Hardie, Esq. Heir,

his son, William, born in 1848.

Lieutenant-Colonel James

Stewart, 42d Highlanders, younger of the two sons of Charles Stewart of

Shambelly, had an only child, Williamina Helen Stewart, who married

Colonel James John Forbes Leith of Whitehaugh, Aberdeenshire, the

representative of the Tolquhoun Forbeses.

_____

The Stewarts of

Ardvoirlich, Perthshire, are descended from James Stewart, called James

the Gross, 4th and only surviving son of Murdoch, duke of Albany, regent

of Scotland, beheaded in 1425. On the ruin of his family he fled to

Ireland, where, by a lady of the name of Macdonald, he had seven sons

and one daughter. James II. created Andrew, the eldest son, Lord

Avandale.

James, the third son,

ancestor of the Stewarts of Ardvoirlich, married Annabel, daughter of

Buchanan of that ilk.

His son, William Stewart,

who succeeded him, married Mariota, daughter of Sir Colin Campbell of

Glenorchy, ancestor of the marquis of Breadalbane, and had several

children. From one of his younger sons, John, the family of Stewart of

Glenbuckie, and from another, that of Stewart of Gartnaferaran, both in

Perthshire, were descended.

His eldest son, Walter

Stewart, succeeded his father, and married Euphemia, daughter of James

Reddoch of Cultobraggan, comptroller of the household of James IV.

His son, Alexander

Stewart of Ardvoirlich, married Margaret, daughter of Drummond of

Drummond Erinoch, and had tow sons, James, his successor, and John,

ancestor of the Perthshire families of Stewart of Annat, Stewart of

Ballachallan, and Stewart of Craigtoun.

The elder son, James

Stewart of Ardvoirlich, rendered himself remarkable by the assassination

of his friend Lord Kilpont, son of the earl of Airth and Menteth, in

Montrose’s camp, near Collace, Sept. 5, 1644. After the bloody deed

Stewart joined the earl of Argyle, then in arms against Montrose, and

was appointed a major in his army. He afterwards distinguished himself,

on the side of the Covenanters, in Leslie’s campaigns. He married

Barbara Murray of Buchanty, Perthshire, with issue.

His eldest son, Robert

Stewart of Ardvoirlich, married Jean, daughter of David Drummond of

Comrie, and had two sons, James and William. The latter married Jean,

daughter of Patrick Stewart of Glenbuckie, and was father of Robert

Stewart, who, on the death of his first cousin, inherited Ardvoirlich.

The elder son, James

Stewart of Ardvoirlich, married Elizabeth, only child of John Buchanan,

last of Buchanan.

His son, Robert Stewart

of Ardvoirlich, died unmarried, in 1756, when his cousin, Robert,

succeeded. This gentleman married Margaret, daughter of John Stewart of

Annat.

His son, William Stewart

of Ardvoirlich, married, in 1797, Helen, eldest daughter of James

Maxtone of Cultoquhey, and had two sons, Robert and William Murray, and

a daughter.

The elder son, Robert

Stewart of Ardvoirlich, succeeded his father Feb. 26, 1838, and died,

unmarried, July 16, 1854.

He was succeeded by his

nephew, William Stewart, who was the eldest of 7 sons of William Murray

Stewart, Bengal Infantry, younger son of William Stewart of Ardvoirlich.

He was an officer in the Bengal Artillery, and died in 1857.

His next brother, Robert,

born in 1829, succeeded him. Heir, his brother, John, lieutenant Bengal

Artillery, born in 1833.

[Preserved at Ardvoirlich,

for centuries, is a lump of pure white rock crystal, about the size and

shape of an egg, bound with four bands of silver, of very antique

workmanship, and known by the Gaelic name of Clach Dearg, the red stone,

arising probably from a reddish tinge it seems to assume when held up to

the light. The water in which the stone has been dipped was formerly

ignorantly considered a sovereign remedy in all diseases of cattle.]

_____

The family of Stewart of

Tonderghie, Wigtownshire, is a branch of the noble house of Galloway,

their progenitor being Sir William Stewart of Dalswinton and Garlies,

who was living in 1479. He obtained Minto, in 1429, after much

opposition from the Turnbulls, the former possessors. He had 4 sons. 1.

Andrew, who predeceased his father. 2. Alexander, who succeeded. 3. Sir

Thomas Stewart of Minto, ancestor of the Lords Blantyre, the Marquises

of Londonderry, in Ireland, and other families. 4. Walter, of Tonderghie,

from whom the Stewarts of Shambelly, the Earls of Blessington in

Ireland, and other families are descended.

In direct descent from

Walter was Alexander Stewart of Tonderghie, who, in 1694, married Janet,

daughter of Hugh M’Guffog, or M’ Guffock, of Rusco Castle. Their son

left an only daughter, Harriet, who married Colonel Dun. The property

being entailed, male or female, Colonel Dun had to assume the surname of

Stewart. This was the first deviation from the direct male line. The

next in succession in the entail was Captain Robert M’Kerlie, through

his grandmother, Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Alexander Stewart of

Tonderghie. (See M’KERLIE.)

Colonel Dun Stewart left

a son, Hugh, and a daughter, Harriet. The son, Hugh, the present

representative, a deputy-lieutenant of Wigtownshire, served as major of

the Galloway militia. The daughter, Harriet, married John Simson of

Barrachan, with issue.

STEWART, DR. MATTHEW, professor of mathematics in the university

of Edinburgh, the son of the Rev. Dugald Stewart, minister of Rothesay,

in the Isle of Bute, was born at that place in 1717. After receiving his

elementary education at the grammar school, being intended by his father

for the church, he was sent to the university of Glasgow, where he was

entered a student in 1734. He made great progress in mathematics, under

the celebrated Dr. Simson, whose predilection for the ancient geometry

he fully adopted. In 1741 he went to Edinburgh to attend the university

lectures there; and, after having been duly licensed, became minister of

Roseneath. In 1746 he published his ‘General Theorems,’ which, although

given without the demonstrations, are of considerable use in the higher

parts of mathematics, and at once placed their discoverer among

geometricians of the first rank. In September 1747 he was elected to the

vacant chair of mathematics in the university of Edinburgh. In this

situation he still more systematically pursued the object which of all

others he most ardently wished to obtain, namely, the application of

geometry to such problems as the algebraic calculus alone had been

thought able to resolve. His first specimen of this kind, the solution

of Kepler’s problem, appeared in the second volume of the ‘Essays of the

Philosophical Society of Edinburgh,’ for 1756; and in the first volume

of the same collection are some other propositions by him. In 1761 he

published his ‘Tracts, Physical and Mathematical,’ in farther

prosecution of his plan of introducing into the higher branches of mixed

mathematics the strict and simple form of ancient demonstration. The

transit of Venus, which took place the same year, led to his essay on

the ‘Distance of the Sun from the Earth,’ which he published in 1763;

and although the correctness of his computation was disputed in some

important points, he declined entering into any controversy on the

subject. A few months previously he had produced his ‘Propositiones

Geometriciae More Veterum Demonstratae,’ consisting of a series of

geometrical theorems, mostly new, and investigated by the analytical

method of the ancient geometers. Soon after, his health began to

decline. IN 1772 he retired to the country, where he spent the remainder

of his life, pursuing his mathematical researches as an amusement; his

duties in the university being performed by his son, the afterwards

celebrated Dugald Stewart, who, in 1775, was associated with him in the

professorship. Dr. Stewart died January 23, 1785, at the age of 68. His

works are:

General Theorems, of considerable use in the higher parts of

Mathematics. Edin. 1746, 8vo.

A Solution of Kepler’s Problem. Edin. 1756, 8vo.

Tracts, Physical and Mathematical; containing an explanation of several

important Points in Physical Astronomy, and a new Method of ascertaining

the Sun’s distance from the Earth by the Theory of Gravitation. Lond.

1761-3, 8vo.

Distance of the Sun from the Earth determined by the Theory of

Gravitation, together with several other things relative to the same

subject; being a supplement to his Physical and Mathematical Tracts.

Edin. 1763, 8vo. The same, 1764, 8vo.

Propositiones Geometricae more veterum demonstratae, ad Geometriam

antiquam illustrandam et promavendam idoneae. Edin. 1763, 8vo.

Pappi Alexandrini Collectionum Mathematicarum libri quarti, Propositio

quarta generalior facta; cui Propositiones aliquot eodem spectantes

adjiciuntur. Ess. Phys. And Lit. i. p. 141. 1754. – Solution of Kepler’s

Problem. Ib, ii. p. 116.

STEWART, DUGALD, a distinguished writer on ethics and

metaphysics, was born in the college of Edinburgh, Nov. 22, 1753. He was

the only son, who survived the age of infancy, of Dr. Matthew Stewart,

professor of mathematics in that university, and Marjory, daughter of

Archibald Stewart, Esq. of Catrine, Ayrshire, writer to the signet. At

the age of seven he was sent to the High School, and, in October 1766,

was entered a student at the college of his native city, where his

studies were chiefly directed to history, logic, metaphysics, and

morals. IN 1771 he removed to the university of Glasgow, to attend the

lectures of the celebrated Dr. Reid; and during the session he composed

his admirable Essay on Dreams, first published in the first volume of

the ‘Philosophy of the Human Mind,’ in 1792.

The declining state of

his father’s health compelled him, in the autumn of 1772, to return to

Edinburgh, and officiate in his stead to the mathematical class in the

university, a task for which, at the early age of nineteen, he was fully

qualified. When he had completed his twenty-first year he was appointed

assistant and successor to his father, on whose death, in 1785, he was

nominated to the vacant chair. In 1778, during Dr. Adam Ferguson’s

absence in America, he supplied his place in the moral philosophy class.

In 1780 he received a number of young noblemen and gentlemen, as pupils

into his house, and, in 1783, he visited Paris in company with the

marquis of Lothian. On his return, he married, the same year, Helen,

daughter of Neil Bannatyne, Esq., merchant in Glasgow, by whom he had

one son. In 1785 he exchanged his chair for that of moral philosophy, to

allow Dr. Ferguson to retire on the salary of mathematical professor,

and thenceforth devoted himself almost exclusively to the prosecution

and culture of intellectual science. In 1787 his wife died, and the

following summer he again visited the continent, with Mr. Ramsay of

Barnton. In 1790 he married Helen D’Arcy Cranstoun, a daughter of the

Hon. George Cranstoun, and authoress of the song, ‘The tears I shed must

ever fall.’

In 1793 he read before

the Royal Society of Edinburgh his Account of the Life and Writings of

Dr. Adam Smith, and the same year he published the ‘Outlines of Moral

Philosophy,’ for the use of his students. In March, 1796, he

communicated to the royal Society his account of the Life and Writings

of Dr. Robertson, and, in 1802, that of the Life and Writings of Dr.

Reid. The Memoirs of Smith, Reid, and Robertson, were afterwards

collected into one volume, and published with additional notes. In 1796

he again took a number of pupils into his house, and, in 1800, he added

a course of lectures on political economy to the usual course of his

chair. So extensive were his acquirements, and so ready his talent for

communicating knowledge, that his colleagues frequently availed

themselves of his assistance in lecturing to their classes, in cases of

illness or absence. In addition to his own academical duties he

repeatedly supplied the place of Dr. John Robison, professor of natural

philosophy. He taught for several months during one winter the Greek

classes of Professor Dalzel; he more than one season taught the

mathematical classes for Mr. Playfair; he delivered some lectures on

logic during an illness of Dr. Finlayson, and he, one winter, lectured

for some time on Belles Lettres for the successor of Dr. Blair.

In 1806 he accompanied

the earl of Lauderdale, when he went on a political mission to Paris. On

the accession of the Whig administration, in that year, a sinecure

office, that of gazette-writer for Scotland, was created for the express

purpose of rewarding Mr. Stewart for the services he had rendered to

philosophy and education, the salary being £300 a-year. “Mr. Stewart’s

personal character and philosophical reputation,” says his biographer,

Mr. Veitch, “rendered his house the resort of the best society of

Edinburgh, at a time when the city formed the winter residence of many

of the Scottish families.” Colonel Stewart, referring to this period,

speaks of his father’s house “as the resort of all who were most

distinguished for genius, acquirements, or elegance in Edinburgh, and of

all the foreigners who were led to visit the capital of Scotland.” “From

an early period of life,” he continued, “he had frequented the best

society both in France and in this country, and he had, in a peculiar

degree, the air of good company. The immense range of his erudition, the

attention he had bestowed on almost every branch of philosophy, his

extensive acquaintance with every department of elegant literature,

ancient or modern, and the fund of anecdote and information which he had

collected in the course of his intercourse with the world, with respect

to almost all the eminent men of the day, either in this country or in

France, enabled him to find suitable subjects for the entertainment of

the great variety of his visitors of all descriptions, who at one period

frequented his house.” He held the first place as a powerful and

impressive lecturer, and his popularity as a lecturer increased to the

last. Among his students were found, not only the youth of Scotland, but

many, and some of the highest rank, from England. The continent of

Europe and America likewise furnished a large proportion of pupils. “As

a public speaker,” says the writer of his biography in the Annual

Obituary of 1829, “he was justly entitled to rank among the very first

of his day; and, had an adequate sphere been afforded for the display of

his oratorical powers, his merit as an orator would have sufficed to

procure him an eternal reputation. The ease, the grace, and the dignity

of his action; the compass and harmony of his voice, its flexibility,

and variety of intonation; the truth with which its modulation responded

to the impulse of his feelings, and the sympathetic emotions of his

audience; the clear and perspicuous arrangement of his matter; the

swelling and uninterrupted flow of his periods, and the rich stores of

ornament which he used to borrow from the literature of Greece and Rome,

of France and England, and to interweave with his spoken thoughts with

the most apposite application, were perfections not possessed by any of

the most celebrated orators of the age. His own opinions were maintained

without any overweening partiality; his eloquence came so warm from the

heart, was rendered so impressive by the evidence which it bore of the

love of truth, and was so free from all controversial acrimony, that

what has been remarked of the purity of purpose which inspired the

speeches of Brutus, might justly be applied to all that he spoke and

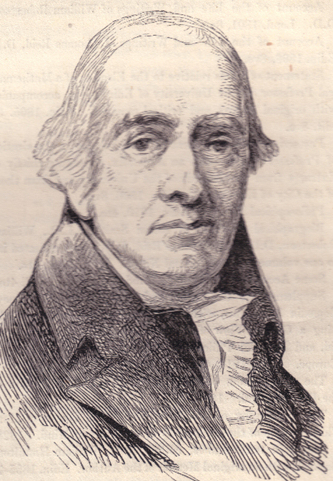

wrote.” His portrait is subjoined: --

[portrait of Dugald Stewart]

In 1810 he relinquished

his professorship, and removed to Kinneil House, a seat belonging to the

duke of Hamilton, on the banks of the Firth of Forth, where he spent the

remainder of his days in retirement. He was a member of the Academies of

Sciences at St. Petersburg and Philadelphia, and other learned bodies.

He died at Edinburgh, June 11, 1828, and was buried in the Canongate

churchyard. A monument to his memory stands on the Calton Hill,

Edinburgh. He left a widow and two children, a son and a daughter, the

former of whom, Lieutenant-colonel Matthew Stewart, has published an

able pamphlet on Indian affairs. His widow, who holds a high place among

the writers of Scottish sons, survived her husband ten years, dying July

28, 1838. She was the sister of the Countess Purgstall, the subject of

Captain Basil Hall’s ‘Schloss Hainfeld,’ and of Mr. George Cranstoun,

advocate, afterwards Lord Corehouse. Dugald Stewart’s works are:

Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind. Lond. 1792, 4to. Likewise

in 8vo. Edin. 1814, vol. 1st, 8vo, vol. 2d, 4to.

Outlines of Moral Philosophy; for the use of Students in the University

of Edinburgh. Edin. 1793, 8vo.

Dr. Adam Smith’s Essays on Philosophical Subjects; with an Account of

the Life and Writings of the author. Lond. 1794, 4to.

Account of the Life and Writings of William Robertson, D.D. Lond. 1801,

8vo.

Account of the Life and Writings of Thomas Reid, D.D. Edin. 1803, 8vo.

Statement of Facts relative to the Election of a Mathematical Professor

in the University of Edinburgh; accompanied with original papers and

critical remarks. Edin. 1805, 3d edit. 8vo.

Postscript to a Statement of Facts relative to the election of Professor

Leslie; with an Appendix, consisting chiefly of Extracts from the

Records of the University and fro those of the City of Edinburgh. Edin.

1806, 8vo.

Philosophical Essays. Edin. 1810, 4to.

Biographical Memoirs of Adam Smith, LL.D., William Robertson, D.D., and

Thomas Reid, D.D.; now collected into one volume, with additional Notes.

Edin. 1811, 4to.

Some Account of a Boy born Blind and Deaf. 1812, 4to.

Supplement to the fourth and fifth editions of the Encyclopaedia

Britannica, with a Preliminary Dissertation, exhibiting a General View

of the Progress of Metaphysical, Ethical, and Political Philosophy,

since the revival of Letters in Europe. Edin. 1816, 4to.

The continuation of the second part of the Philosophy of the Human Mind.

1827.

The Philosophy of the Active and Moral Powers of Man. Third volume of

the Philosophy of the Human Mind. 1828.

Works in ten volumes, edited by Sir William Hamilton, Baronet, with an

original Memoir of the Author. Edin. 1855-7.

STEWART, DAVID, of Garth, a major-general in the army, and

popular writer on the Highlanders, was the second son of Robert Stewart,

Esq. of Garth, in Perthshire, where he was born in 1772. In 1789 he

entered the 42d regiment as an ensign, and in 1792 was appointed

lieutenant. He served in the campaigns of the duke of York in Flanders,

and was present at the siege of Nieuport and the defence of Nimeguen. In

October 1795, his regiment forming part of the expedition under Sir

Ralph Abercromby, he embarked for the West Indies, where he was actively

engaged in a variety of operations against the enemy’s settlements,

particularly in the capture of St. Lucia; and was afterwards employed

for seven months in unremitting service in the woods against the Caribbs

in St. Vincent. In 1706 he was promoted to the rank of captain-

lieutenant, and in 1797 he served in the expedition against Porto Roco;

after which he returned to England; but was almost immediately ordered

to join the head-quarters of his regiment at Gibraltar. In 1799 he

accompanied the expedition against Minorca; but was taken prisoner at

sea, and after being detained for five months in Spain was exchanged. In

December 1800 he was promoted to the rank of captain, a step which, like

all his subsequent ones, was given him for his services alone. In 1801

he received orders to join Sir Ralph Abercromby against Egypt. At the

landing in the Bay of Aboukir, on the morning of March 8, 1801, he was

one of the first who leaped on shore from the boats; and by his gallant

bearing he contributed greatly to the dislodging of the enemy from their

position on the Sandhills. He also distinguished himself in the

celebrated action of the 21st March, where he received a severe wound,

which prevented him from taking part in the subsequent operations of the

campaign.

Some time after his

return from Egypt, he recruited, as was then the custom, for his

majority, and such was his popularity among his countrymen, that, in

less than three weeks, he raised his contingent of 125 men. He now, in

1804, entered the second battalion of the 78th or Ross-shire

Highlanders, with the rank of major, and in September 1805 accompanied

the regiment to Gibraltar, where it continued to perform garrison duty

till the ensuing May, when it embarked for Sicily, to join in the

descent which General Sir John Stuart was then mediating on Calabria. At

the battle of Maida, July 4, 1806, where he greatly distinguished

himself, he was again severely wounded, which forced him to retire from

the field, and ultimately to return to Britain. In April 1808 he was

promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, with a regimental

appointment to the third West India Rangers, then in Trinidad. In 1810

he was present at the capture of Guadaloupe, for which service, and that

at Maida, he was rewarded with a medal and one clasp, and was

subsequently appointed a companion of the Bath. In 1814 he became

colonel, and the year following retired upon half-pay.

In 1822 he published his

well-known ‘Sketches of the Character, Manners, and present State of the

Highlanders of Scotland, with details of the Military Service of the

Highland Regiments,’ a most interesting work, which added greatly to his

reputation. A few months after, he succeeded to the patrimonial

inheritance of his family, by the deaths, within a short period of each

other, of his father and elder brother. The success of his ‘Sketches,’

and an ardent desire to do justice to the history and character of the

Highland clans, induced him to commence collecting materials for a

history of the Rebellion of 1745; but the difficulties he encountered in

obtaining accurate information soon caused him to abandon the task. In

1825 he was promoted to the rank of major-general, and soon after was

appointed governor and commander-in-chief of the island of St. Lucia, in

the capture of which from the French he had formerly assisted. He died

at St. Lucia, of fever, December 18, 1829, while actively occupied with

many important improvements which he had projected for the prosperity of

the island. |