|

SHARP, a surname

derived from the French heraldic term Escharp. Sir George Mackenzie, in

his Science of Heraldry, says that the word fesse, from the Latin

fascia, a scarf, represents the scarf of a warrior en escharp, “and from

bearing argent a fesse azure the first of the Sharps, who came from

France with King David, was called Monsieur de Escharp, and by

corruption Sharp.” (See Nisbet’s Heraldry, vol. i. p. 43.)

SHARP, JAMES, a prelate whose name is connected with the

establishment of Episcopacy in Scotland, was born in the castle of

Banff, May 4, 1613. He was the son of William Sharp Sheriff-clerk of

Banffshire, whose father, David Sharp, had been a merchant in Aberdeen.

His mother was Isobel Lesly, daughter of Lesly of Kininvy, a near

relative of the earl of Rothes. Being early destined for the ministry,

he was placed at Marischal college, Aberdeen, on quitting which he

proceeded into England, and visited the universities of Oxford and

Cambridge. On the recommendation of the celebrated Alexander Henderson,

he subsequently obtained the professorship of philosophy in the

university of St. Andrews. In 1648, at the request of Mr. James Bruce,

minister of Kingsbarns, he was presented by the earl of Crawford to the

church and parish of Crail, on which he resigned his chair. Remarkable

in his early career for his attachment to Presbyterianism, he enjoyed

the full confidence, and took part in all the councils, of the leaders

of the church of Scotland, and in 1650 was elected one of the ministers

of Edinburgh, but the troubles of the time consequent on Cromwell’s

invasion of Scotland prevented his acceptance of the call.

In August 1651 he and a

number of other ministers, with some of the nobility, were surprised by

a party of the English at Alyth, in Angus, at the time General Monk was

besieging Dundee, and being put on board a ship at Broughty Ferry, were

carried prisoners to London. He seems to have obtained the favour of

Cromwell, who set him at liberty, while the rest were retained for some

time in confinement.

When the division took

place among the Presbyterians of Resolutioners and Protesters, Sharp

joined the former, and in 1657 was sent by his party to London to plead

their cause with Cromwell, in opposition to Messrs, James Guthrie,

Patrick Gillespie, and the other commissioners from the Protesters. On

this occasion he so much distinguished himself by his address that

Cromwell remarked to the bystanders, “That gentleman, after the Scotch

way, should be called Sharp of that ilk.” In January 1660, on the

prospect of the Restoration, he was again, with five ministers of

Edinburgh, dispatched to London by the leading ministers on the side of

the Resolutioners, to communicate the views of their party to Monk. He

remained in London till May 4, when he was sent by Monk to Breda, to

procure the sanction of Charles II. to the proposed settlement of the

ecclesiastical affairs of Scotland. He returned to London, May 26, and

appears to have continued there till about the middle of August, being

all the time in close communication with the principal leading persons

and parties of the day, maintaining, at the same time, an active

correspondence with the Presbyterian clergy of Scotland, who placed

their entire confidence in him. A full abstract of his letters on the

occasion, which are preserved in the library of the university of

Glasgow, will be found in Wodrow’s History.

When he returned to

Scotland, he delivered to Mr. Robert Douglas a letter from the king, to

be communicated to the presbytery of Edinburgh, in which his majesty

declared his resolution to protect and preserve the government of the

Church of Scotland, as “settled by law;” a phrase which completely

blinded the clergy to the designs of Charles, and their representative,

Sharp, who appears by this time to have been gained over, for the

introduction of prelacy. On the subversion by parliament of the

Presbyterian Church in August 1661, the royal pledge was thus at once

transferred to the support of that episcopacy which had been overthrown

in 1638, and which the people of Scotland could never be prevailed upon

to recognize as the national religion.

During his absence in

England, Sharp had been elected professor of divinity in St. Mary’s

college, St. Andrews. He was also appointed his majesty’s chaplain for

Scotland, with a salary of £200 per annum. Having, on the rising of

parliament, again gone up to London, he was nominated archbishop of St.

Andrews, and he and three others were consecrated with great pomp at

Westminster, December 15, 1671. On his return from London in April, he

and his coadjutors, Fairfoul, bishop of Glasgow, and Hamilton, bishop of

Galloway, entered Edinburgh in great state, and soon after Sharp went

over to Fife, and having dined at Abbotshall with Sir Andrew Ramsay, on

the 15th of that month, he proceeded to Lesley House. The earl of Rothes

had prepared a sort of triumphal progress for him, by writing to several

persons and corporations to meet him at different points of the route,

so that the cavalcade swelled to seven or eight hundred horsemen. Among

the company were the earls of Rothes, Leven, and Kellie; Lord Newark;

Sir William Scott of Ardross, John Lundie of Lundie, Dr. Alexander

Martin of Strathendrie, Arthur Forbes of Rires, Thomas Alexander of

Scaddoway, and Sir John Gibson of Durie. Only two ministers, however,

were present. In May 1662 Sharp and Fairfoul, with Leighton, bishop of

Dunblane, proceeded to consecrate the ten other bishops of Scotland, the

parliament having postponed its meeting till the bishops should be ready

to take their seats.

The unrelenting

persecution of the faithful adherents of the Covenant which followed

Sharp’s elevation to the primacy, increased the general odium in which

his character was held, from the belief, which was common among them,

that he had betrayed the cause of the church. On Saturday, July 9, 1668,

he narrowly escaped assassination, by being shot at with a pistol, as he

was entering his carriage in the High Street of Edinburgh, by Mr. James

Mitchell, who was not apprehended till five years afterwards, and who

was executed, in 1678, in violation of a solemn promise to the contrary.

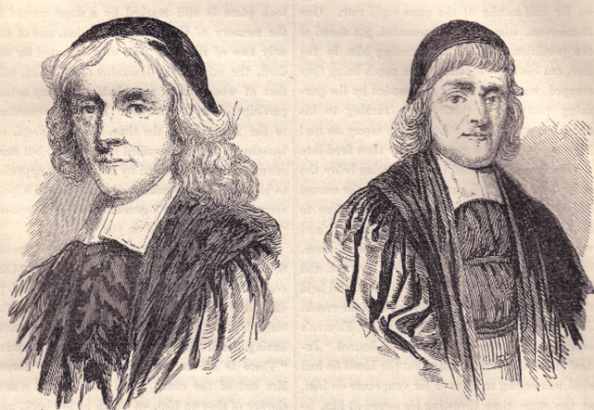

Two portraits of

Archbishop Sharp are subjoined, the one representing him in middle life,

and the other at a more advanced age. When his features had become

harsher:

[portraits of archbishop James Sharp]

In changing sides, and

turning from Presbyterianism to Episcopacy, Sharp acted only as Leighton

did, but the difference between the two men was that Leighton was

conscientious and sincere, and wholly devoted to his Episcopal and

ministerial duties, while Sharp was more a political than a religious

adherent of his party, and took the lead in the persecution of the

Covenanters; and hence the very different estimate which history has

made of these prelates.

In 1679 occurred that

memorable act of vengeance which has been differently represented by

different historians. On Saturday, May 3, in that year, while traveling

with his eldest daughter, Isabel, from Edinburgh by Kennoway to St.

Andrews, the primate’s carriage was met on Magus Moor, within three

miles of the latter town, by nine of the more zealous of the persecuted

Presbyterians, of whom Balfour of Burley, Russell of Kettle, and

Hackston of Rathillet were three. They were waiting there to intercept

Carmichael, sheriff-substitute of Fife, an active and unscrupulous agent

of the archbishop and the council in oppressing the Covenanters. On

Rathillet declining to act as captain, Balfour of Burley, “a little man,

squint-eyed, and of a very fierce aspect,” was chosen to command the

party. The following is the account given of the murder of the

archbishop: Soon after passing the farm-house of Magus, between eleven

and twelve o’clock, the coachman, looking round, saw the conspirators

riding at full speed, pistols in hand, with swords drawn, and hanging

from their wrists; and he immediately called to the postillion to drive

on, for he suspected their pursuers had evil intentions. Finding his

coach driven at such an increased speed, his grace looked out to see

what was the cause. Russell was by this time so near as to see and

recognize the archbishop. He immediately fired and called to the rest to

come up. The primate urged the coachman to drive on, and he kept on for

half-a-mile at the same rapid rate. One Henderson, who was best mounted,

got ahead of the postillion, and, after wounding him in the face, cut

his horse’s hams. The coach being thus stopped, was immediately

surrounded by the pursuing party. On this, Sharp, turning to his

daughter, exclaimed, “Lord have mercy on me! My poor child, I am gone!”

They then fired into the coach, and wounded him two inches below the

collar-bone, the ball entering between the second and third ribs. This

pistol was fired so close to his body that the wadding burnt his gown,

and was rubbed off by Miss Sharp. One of them, named George Fieman, then

rode forward, and seized the horses’ reins on the near side, and held

them till George Balfour had fired into the coach. James Russell

alighted, and, taking Fieman’s sword, opened the coach door, and desired

“Judas” to come forth, saying that the blood he had shed was crying to

Heaven for vengeance on him, at the same time thrusting his sword at

him, he wounded him in the region of the kidneys. John Balfour, who was

still on horseback, also commanded him to come forth, and fired his

pistol at him. James Russell desired him again to come forth, “and make

ready for death, judgment, and eternity.” The archbishop addressing

them, said, “Gentlemen, if you will spare my life, whatever else you

will please to do, you shall never be questioned for it.” His daughter

now sprung out, and falling on her knees, with tears and prayers begged

her father’s life, but she appealed to them in vain. Sharp then came out

of the coach, and said that “he did not know that he had ever injured

any of them, but if he had, he was ready to make reparation, beseeching

them to spare his life, and he would never trouble them for that

violence; but prayed them to consider, before they brought the guilt of

innocent blood upon themselves.” After receiving various wounds from

their swords, Balfour gave him a tremendous cut above the left eye, on

which he exclaimed, “Now you have done the turn,” and then fell forward,

with his head resting on his arms. Miss Sharp was all this time held by

Andrew Guillan, with the view of securing her from dander, when

interposing herself between her father and the conspirators. The spot

where the assassination took place is still marked by a stone erected to

the memory of Guillan, a weaver lad, one of the only two of the party

who were executed for the deed, the other being Hackston of Rathillet,

neither of whom, it is remarkable, had any actual participation in the

murder. Rathillet, according to the historians of the time, remained

aloof, on horseback, his face muffled in his cloak, but near enough to

be recognized by Sharp, who appealed to him, as a gentleman, to protect

him, to which, according to Guillan’s account, Rathillet replied, “I

shall never lay hand on you.”

According to “the

evidence of two persons who were present,” as preserved by Kirkton,

(Secret and True History of the Kirk of Scotland, p. 421,) the

conspirators first “poured in on the bishop’s body a shower of ball;”

but one of them having heard his daughter say to the coachman, “There is

life in my father yet,” they “forced him out of the coach,” and

“discharged a new shower of shot on him, on which he fell back, and lay

as dead. Some gave him a prick with a sword, on which he raised himself.

Then they saw shooting would not doe, and drew their swords. On the

sight of cold iron his courage failed, and he made hideouse schriecks as

ever wer heard; one of them gave him a blow on the face, and his chafts

fell down; then he spoke somewhat, but it could not be understood; they

redoubled their stroaks and killed him outright.” The assassination of

Archbishop Sharp forms the subject of an admirable painting by Sir

William Allan, which has been engraved. The event brought much

opprobrium on the Presbyterians, “though unjustly,” says Sir Walter

Scott, “for the moderate persons of that persuasion, comprehending the

most numerous, and by far the most respectable, of the body, disowned so

cruel an action, although they might be, at the same time, of opinion

that the archbishop, who had been the cause of many men’s violent death,

merited some such conclusion to his own.”

Treated by Presbyterians

and Presbyterian authors as an apostate and traitor, Archbishop Sharp

has, on the other hand, received from Episcopalian writers, with the

exception of Bishop Burnet, the highest encomiums and commendations. Mr.

Elliott says of him, “I can justly, and on good grounds, say that he was

a most reverent and grave churchman, very strict and circumspect in his

course of life; a man of great learning, great wit, and no less great

and solid judgment, a man of great council, most faithful in his

Episcopal office, and most vigilant over the enemies of the church.”

By his wife, Helen

Moncrieff, daughter of the laird of Randerston, Archbishop Sharp had a

son, Sir William Sharp, and three daughters, the eldest of whom was

married to Erskine of Cambo, the 2d to Cunningham of Barns, and the

youngest, Margaret, to William, eleventh Lord Saltoun. A magnificent

marble monument was erected by his son over the place where his remains

were interred in the parish church of St. Andrews.

SHARPE, CHARLES KIRKPATRICK, an accomplished amateur in

literature, art, and music, was born about 1781. He sprung from a house

which, in more than one generation, had been distinguished by a taste

for literature. In 1690 his ancestor, John Sharpe, Esq., purchased from

the earl of Southesk, the estate and castle of Hoddam, Dumfries-shire,

which has ever since continued in the family. His grand-uncle, Matthew

Sharpe of Hoddam, fought at Preston on the side of Prince Charles, and

died in 1769, at the age of 76. He corresponded with David Hume, the

historian, who addressed to him one of his most characteristic letters.

His father, Mr. Charles Sharpe of Hoddam, was a grandson of Sir Thomas

Kirkpatrick of Closeburn, the second baronet of his line. Burns, in 1790

or 1791, wrote to him a humorous letter under a fictitious signature,

enclosing three stanzas, written by him to what he calls “a charming

Scots air” of Mr. Sharpe’s composition. In this letter he says, “You, I

am told, play an exquisite violin, and have a standard taste in the

belles letters.” The subject of this notice was his second son, the

eldest son being General Matthew Sharpe of Hoddam, M.P. for the Dumfries

burghs from 1832 to 1841. His mother was a daughter of Renton of

Lamberton, a lady whose charms have been commemorated by Smollett in

Humphrey Clinker. His brother was a Whig of extremely liberal politics,

but his himself was a Tory of the old high cavalier school. He was

educated at Christ church, Oxford, and at one period was designed for

the ministry in the Church of England, but never took orders. Before he

had attained his thirtieth year he had fixed his residence in Edinburgh,

devoting his time principally to the cultivation of literature, music,

and the fine arts.

His first appearance in

print was in the ‘Border Minstrelsy,’ edited by Sir Walter Scott, to

which publication he contributed, in 1803, ‘The Tower of Repentance,’ a

ballad of some merit. In 1807 he published at Oxford a volume of

‘Metrical Legends and other Poems,’ 8vo. He showed, however, higher

skill as an artist than genius as a poet. At Abbotsford is his original

drawing of Queen Elizabeth ‘dancing high and disposedly” before the

Scottish envoy, Sir James Melville, who had excited her jealousy by

commendations of the exquisite grace with which Mary Stuart led the

dance at Holyrood or Linlithgow. On receiving it from Mr. Sharpe, then

at Oxford, Sir Walter Scott, in a letter dated 30th December 1808,

earnestly endeavoured to enlist him as a contributor to two works which

he was at that time busy in projecting, viz., the ‘Quarterly Review,’

and the ‘Edinburgh Annual Register.’ Mr. Sharpe’s drawing of the

‘Marriage of Muckle Mou’d Meg, illustrative of a well-known incident in

border history, like his ‘Queen Elizabeth dancing,’ is a fine specimen

of the humorous. Etchings of them were made, as well as of the ‘Feast of

Spurs,’ and many other things of the same kind from his ever ready

pencil.

In 1817 Mr. Sharpe edited

the ‘Secret and True History of the Church of Scotland, from the

Restoration to the year 1678, by the Rev. James Kirkton, with an account

of the murder of Archbishop Sharpe, by James Russell, an actor therein,’

Edinburgh, 4to. To this work he appended a series of Notes remarkable

for their piquancy. In 1820 he published an edition of the Rev. Robert

Law’s ‘Memorialls, or the considerable things that fell out within this

island of Great Britain from 1638 to 1684,’ Edinburgh, 4to. This work,

it is said in Watt’s ‘Bibliotheca Britannica,’ forms a collection of

perhaps the best selected tales of witchcraft and wizardry which has

been yet published. IN 1823 he produced his ‘Ballad Book,’ a small

collection of Scottish ballads, inscribed to the editor of the Border

Minstrelsy. In 1827 he edited ‘The Life of Lady Margaret Cunninghame,’

and a narrative of the ‘Conversion of Lady Warristoun,’ IN 1828 he

edited for the Bannatyne Club the ‘Letters of Lady Margaret Kennedy,’ or

Burnet, to John, duke of Lauderdale, and in 1829, for the same Club, the

‘Letters of Archibald, Earl of Argyle,’ to the same nobleman. He also

furnished the curious engravings illustrative of Sir Richard Maitland’s

‘History of the House of Seton to the year 1559, with the continuation

by Alexander Viscount Kingston to 1687,’ printed for the Maitland Club

in 1829. A small collection of his characteristic etchings appeared in

1833, under the title of ‘Portraits by an Amateur.’ In 1837 he edited

‘Minuets and Songs by Thomas sixth Earl of Kelly,’ and ‘Sargundo, or the

Valiant Christian,’ – a Romanist song of triumph for the victory of the

Popish earls of Glenlivat in 1594. Of these works the impressions were

limited, and they are not much known, except to antiquaries and

bibliographers.

When Sir Walter Scott

began to keep a diary in November 1825, about the first portrait he

inscribed in it, was that of the subject of this notice. “Charles

Kirkpatrick Sharpe,” it begins, “is another very remarkable man. He was

bred a clergyman, but never took orders. He has infinite wit, and a

great turn for antiquarian lore, as the publications of Kirkton, &c.,

bear witness. His drawings are the most fanciful and droll imaginable –

a mixture between Hogarth and some of those foreign masters who painted

temptations of St. Anthony, and such grotesque subjects. As a poet he

has not a very strong touch. Strange that his finger-ends can describe

so well what he cannot being out clearly and firmly in words! If he were

to make drawing a resource it might raise him a large income. But though

a lover of antiquities, and, therefore, of expensive trifles, Charles

Kirkpatrick Sharpe is too aristocratic to use his art to assist his

purse. He is a very complete genealogist, and has made many detections

in Douglas and other books on pedigree, which our nobles would do well

to suppress if they had an opportunity. Strange that a man should be so

curious after scandal of centuries old! Not but that Charles loves it

fresh and fresh also; for being very much a fashionable man, he is

always master of the reigning report, and he tells the anecdote with

such gusto that there is no helping sympathizing with him – a

peculiarity of voice adding not a little to the general effect. My idea

is that Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, with his oddities, tastes, satire,

and high aristocratic feelings, resembles Horace Walpole – perhaps in

his person also in a general way.” One of the great publishing houses of

London offered him a large sum for his autobiography, but he refused the

offer. Mr. Sharpe died 18th March 1851, aged upwards of 70. His

collection of antiquities was among the richest which any private

gentleman had ever accumulated in Scotland. |