|

MOORE, JOHN, M.D.,

an eminent physician and miscellaneous writer, the son of the Rev.

Charles Moore, an Episcopalian clergyman at Stirling, and his wife, the

daughter of John Anderson, Esq., of Dowhill near Glasgow, was born in

Stirling in 1730. He was educated at the university of Glasgow, and

began the study of medicine and surgery under the care of Dr. Gordon, an

eminent practitioner in that city. At the same time, he attended the

anatomical demonstrations of Professor Hamilton, and the medical

lectures of the celebrated Dr. Cullen, then professor of medicine at

Glasgow. In 1747 he went to the Netherlands, where the allied army was

then serving, and attended the military hospitals at Macstricht. Soon

after, he was recommended by Dr. Middleton, director-general of military

hospitals, to the earl of Albemarle, colonel of the Coldstream Guards,

then quartered at Flushing, and was appointed assistant-surgeon of that

regiment, which he accompanied to Breda. On the conclusion of peace in

the summer of 1748, he returned to England.

After remaining some time

in London, during which he attended the anatomical lectures of Dr.

William Hunter, Mr. Moore went over to Paris to prosecute his studies in

the hospitals of that city. Soon after his arrival, the earl of

Albemarle, then British ambassador at the court of France, appointed him

surgeon to his household. Two years afterwards, he was induced to become

the partner of his old master, Dr. Gordon, surgeon at Glasgow; and on

the latter subsequently commencing practice as a physician, Mr. Moore

went into partnership with Mr. Hamilton, professor of anatomy in Glasgow

college.

In the spring of 1772,

Mr. Moore obtained the diploma of M.D. from the university of Glasgow.

He was soon after engaged by the duchess of Argyle as medical attendant

to her son, the duke of Hamilton, who was in a delicate state of health;

and whom he accompanied to the continent, where he spent five years in

traveling with his grace. On their return in 1778, Dr. Moore removed his

family from Glasgow to London, and in 1779 he published ‘A View of

Society and Manners in France, Switzerland, and Germany,’ in 2 vols.

8vo. In 1781 appeared ‘A View of Society and Manners in Italy,’ 2 vols.

8vo. In 1786 he published his ‘Medical Sketches;’ and in 1789, a novel,

entitled ‘Zeluco.’

In the summer of 1792 he

paid a short visit to Paris, as medical attendant of the earl of

Lauderdale, and having witnessed some of the principal scenes of the

French Revolution, on his return he published ‘A Journal during a

residence in France, 1792.’ Dr. Moore edited a collected edition of

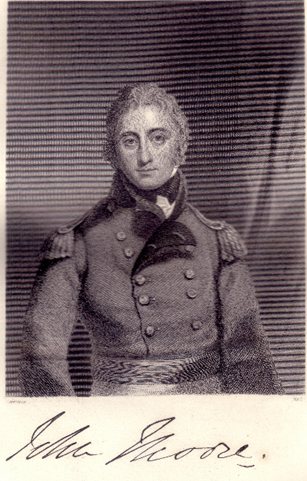

Smollett’s Works. He died at London, Feb. 20, 1802. His portrait is

subjoined:

[portrait of John Moore, M.D.]

He had two sisters, one

married to the Rev. Dr. Wm. Porteous, one of the ministers of Glasgow,

and the other to George Macintosh, Esq. of Dunhatton. The eldest son of

the latter, Charles Macintosh, F.R.S., celebrated for his chemical

discoveries, was the inventor of the gentleman’s covering called a

macintosh, and other gutta percha articles. Dr. Moore’s works are:

A View of Society and Manners in France, Switzerland, and Germany. Lond.

1779, 2 vols. 8vo. Several editions, and translated into the French,

German, and Italian languages.

A View of Society and

Manners in Italy. London, 1791, 2 vols. 8vo.

Medical Sketches, in two

Parts. London, 1786, 8vo.

Zeluco, a Novel. London,

1789, 2 vols. 8vo.

A Journal during a

Residence in France, from the beginning of August to the middle of

December, 1792. London, 1792, 2 vols, 8vo.

A View of the Causes and

Progress of the French Revolution. London, 1795, 2 vols. 8vo.

Edward: a Novel. London,

1796.

Mordaunt, a Novel.

London, 1800, 3 vols. 8vo.

MOORE, SIR JOHN, a distinguished British commander, son of the

subject of the preceding article, by his wife, a daughter of Professor

Simson, of the university of Glasgow, was born in that city, Nov. 13,

1761. He received the rudiments of his education at the local High

School, and at the age of eleven accompanied his father, then engaged as

traveling physician to the duke of Hamilton, to the continent. In 1776

he obtained an ensign’s commission in the 51st foot. He was next

promoted to a lieutenancy in the 82d regiment, and served in America

till the conclusion of the war in 1783, when his regiment being reduced,

he was put upon half-pay. On his return to Britain, with the rank of

captain, he resumed the studies of fortification and field tactics, and

on the change of ministry, which soon followed the peace, he was, by the

Hamilton influence, elected to represent the Lanark district of burghs

in parliament. In 1787 he obtained the rank of major in the 4th

battalion of the 60th regiment, and in 1788 he exchanged into his first

regiment, the 51st. In 1790 he succeeded by purchase to the

lieutenant-colonelcy, and in 1791 he went with his regiment to

Gibraltar.

In 1794 Colonel Moore was

ordered to accompany the expedition for the reduction of Corsica, and at

the siege of Calvi he was appointed by General Charles Stuart to command

the reserve, at the head of which he gallantly stormed the Mozzello

fort, amidst a shower of bullets, hand grenades, and shells, that

exploded among them at every step. Here he received his first wound, in

spite of which he mounted the breach with his brave followers, who drove

the enemy before them. Soon after the surrender of the garrison, he was

nominated adjutant-general, as a step to farther promotion.

A disagreement having

taken place between the British commander, General Stuart, and Sir

Gilbert Elliot, the viceroy of the island, the former was recalled, and

colonel Moore was ordered by the latter to quit Corsica within 48 hours.

He returned to England in November 1795, and was almost immediately

promoted to the rank of Brigadier-general in an expedition against the

French West India islands. He sailed from Spithead February 28, 1796, to

join the army under Sir Ralph Abercromby at Barbadoes, where he arrived

April 13. His able services under this gallant veteran during the West

India campaign, especially in the debarkation of the troops at St.

Lucia, and the siege of Morne Fortunee, were, as declared by the

commander-in-chief in the public orders, “the admiration of the whole

army.”

On the capitulation of

St. Lucia, Sir Ralph appointed General Moore commandant and governor of

the island, a charge which he undertook with great reluctance, as he

longed for more active service. But he performed his duty with his

accustomed energy and success, notwithstanding the hostility of the

natives, and the numerous bands of armed Negroes that remained in the

woods. Two successive attacks of yellow fever compelled him to return to

England in August 1797, when he obtained the rank of major-general. In

the subsequent December, his health being completely re-established, he

joined Sir Ralph Abercromby in Ireland as brigadier-general, and during

the rebellion of 1798 was actively engaged. At Horetown, he defeated a

large body of the rebels under Ruche, and immediately encamped near

Wexford, which he delivered from the insurgents.

In the disastrous

expedition to Holland, in August 1799, he had the command of a brigade

in the division of the army under Sir Ralph Abercromby; and in the

engagement of the 2d October, he received two wounds, which compelled

him to return to England. In 1800 he accompanied Abercromby in the

expedition to Egypt; and, at the disembarkation of the troops, the

battalion which he commanded carried by assault the batteries erected by

the French on a neighbouring eminence of sand to oppose their landing.

At the battle of Aboukir, March 21, where he was general officer of the

day, his coolness, decision, and intrepidity, greatly contributed to the

victory, which, however, was dearly purchased with the life of Sir Ralph

Abercromby. In this battle General Moore received a dangerous wound in

the leg by a musket-ball, which confined him first on board one of the

transports, and afterwards in the neighbourhood of Rosetta, till the

conclusion of the expedition. He returned home in 1801, in time to

soothe the last moments of his venerable father; on whose death he

generously conferred an annuity on his mother, the half of which only

she would accept.

After this period,

General Moore was encamped with an advanced corps at Sandgate, on the

Kentish coast, opposite to Boulogne, preparing for the threatened

invasion of the French. As he largely enjoyed the confidence of the duke

of York, then commander-in-chief, he was engaged, at his own request, in

a camp of instruction, in training several regiments as light infantry,

and the high state of discipline to which he brought them was of

essential service in the subsequent campaigns in the Peninsula. Towards

the end of 1804, General Moore’s merits induced the king to confer on

him the order of the Bath. In 1806 he was sent to Sicily, where he

served under General Fox, and in the following year he was appointed

commander-in-chief of all the troops in the Mediterranean. In May 1808

he was dispatched, at the head of 10,000 men, to Sweden, with the view

of assisting the gallant but intractable sovereign of that country,

Gustavus Adolphus IV., in the defence of his dominions, then threatened

by France, Russia, and Denmark; but refusing to comply with the

extravagant demands of that eccentric monarch, he was placed under

arrest. He had the good fortune, however, to effect his escape, and

immediately sailed with the troops for England. On his arrival off the

coast, his landing was prevented by an order to proceed to Portugal, to

take part in the expedition against the French in that country, under

the command of Sir Harry Burrard.

After the liberation of

Portugal, the troops were preparing to advance into Spain, when a letter

from Lord Castlereagh, dated September 25, 1808, arrived at Lisbon,

appointing Sir John Moore commander-in-chief of an army of 30,000

infantry and 5,000 cavalry, to be employed in the north of the

Peninsula, in co-operating with the Spanish forces against the French

invaders. He began his march on the 18th October, and on the 13th of

November he reached Salamanca, where he halted to concentrate his

forces, and where, distracted by every species of disappointment and

false information, and deluded by the representations of Mr. Frere, the

British ambassador in Spain, he remained for some time uncertain whether

to advance upon Madrid, or fall back upon Portugal. At length, learning

that the whole of the disposable French armies in the Peninsula were

gathering to surround him, he commenced, on the evening of December 24,

a rapid march to the coast, through the mountainous region of Galicia,

and after the most masterly retreat that has been recorded in the annals

of modern warfare, conducted, as it was, in the depth of winter, and

while pressed on all sides by the skilful and harassing manoeuvres of

the pursuing enemy, he arrived at Corunna, on January 11, 1809, with the

army under his command almost entire and unbroken. In this memorable

retreat 250 miles of country had been traversed, and mountains, defiles,

and rivers had been crossed, amidst sufferings and disasters almost

unparalleled, and yet not a single piece of artillery, a standard, or a

military trophy of any kind, had fallen into the hands of the pursuing

enemy.

Finding that the

transports, which had been ordered round from Vigo, had not arrived, Sir

John Moore quartered a portion of the troops in the town of Corunna, and

the remainder in the neighbouring villages, and made the dispositions

that appeared to him most advisable for defence against the enemy. The

transports anchored at Corunna on the evening of the 14th, and the sick,

the cavalry, and the artillery were embarked in them, except twelve six-pounders,

which were retained for action. Several general officers, seeing the

disadvantages under which either an embarkation or a battle must take

place, advised Sir John Moore to send a flag of truce to Soult, and open

a negotiation to permit the embarkation of the army on terms; but, with

the high-souled courage of his country, Moore indignantly spurned the

proposal as unworthy of a British army, which, amidst all its disasters,

had never known defeat.

The French, assembled on

the surrounding hills, amounted to 20,000 men, and their cannon, planted

on commanding eminences, were larger and more numerous than the British

guns. The British infantry, to the number of 14,500, occupied a range of

heights, enclosed by three sides of the enemy’s position, their several

divisions, under the command of Generals Baird, Hope (afterwards fourth

earl of Hopetoun), Paget (afterwards first marquis of Anglesey), and

Frazer, being thrown up to confront every point of attack.

About two o’clock in the

afternoon of the 16th, a general movement was observed along the French

line; and on receiving intelligence that the enemy were getting under

arms, Sir John Moore rode immediately to the scene of action. The

advanced pickets were already beginning to fire at the enemy’s light

troops, who were pouring rapidly down the hill on the right wing of the

British. Early in the battle Sir David Baird, while leading on his

division, had his arm shattered with a grape-shot, and was obliged to

leave the field. At this instant the French artillery plunged from the

heights, and the two hostile lines of infantry mutually advanced beneath

a shower of balls. They were still separated from each other by stone

walls and hedges. A sudden and very able movement of the British gave

the utmost satisfaction to Sir John Moore, who had been watching the

manoeuvre, and he cried out, “That is exactly what I wished to be done.”

He then rode up to the 50th regiment, commanded by Majors Napier and

Stanhope, who had got over an enclosure in their front, and were

charging most valiantly. The general, delighted with their gallantry,

exclaimed, “Well done, the 50th! Well done, my majors!” They drove the

enemy out of the village of Elvina with great slaughter. In this

conflict, Major Napier, advancing too far, was wounded and taken

prisoner, and Major Stanhope received a ball through his heart, which

killed him instantaneously.

Sir John Moore proceeded

to the 42d, and addressed them in these words, “Highlanders, remember

Egypt!” They rushed on, driving the French before them. In this charge

they were accompanied by Sir John, who sent Captain (afterwards first

Viscount) Hardinge, to order up a battalion of guards to the left flank

of the Highlanders, upon which the officer commanding the light company,

conceiving that as their ammunition was nearly expended, they were to be

relieved by the guards, began to withdraw his men; but Sir John,

perceiving the mistake, said, “My brave 42d, join your comrades;

ammunition is coming, and you have your bayonets.”

When the contest was at

the fiercest, Sir John, who was anxiously watching the progress of the

battle, was struck in the left breast by a cannon-ball, which carried

away his left shoulder, and part of the collar-bone, leaving the arm

hanging by the flesh. The violence of the stroke threw him from his

horse, Captain Hardinge, who had returned from executing his commission,

immediately dismounted, and took him by the hand. With an unaltered

countenance he raised himself, and looked anxiously towards the

Highlanders, who were hotly engaged. Captain Hardinge assured him that

the 42d were advancing, on which his countenance brightened. Hardinge

tried in vain to stop the effusion of blood with his sash, then, with

the help of some Highlanders and Guardsmen, he placed the general upon a

blanket. He was lifted from the ground by a Highland sergeant and six

veteran soldiers of the 42d, and slowly Conveyed towards Corunna. In

raising him, his sword touched his wounded arm, and became entangled

between his legs. Captain Hardinge was in the act of unbuckling it from

his waist, when he said, in his usual tone, and with the true spirit of

a soldier, “It is as well as it is; I had rather it should go out of the

field with me.” When the surgeons arrived, he said to them, “You can be

of no service to me; go to the soldiers, to whom you may be useful.” As

he was borne slowly along, he repeatedly caused those who carried him to

halt and turn round, to view the field of battle; and he was pleased

when the firing grew faint in the distance, as it told of the retreat of

the French.

On arriving at his

lodgings he was placed on a mattress on the floor. He was in great

agony, and could only speak at intervals. He said to Colonel Anderson,

who had been his companion in arms for more than twenty years, and who

had saved his life at St. Lucia, “Anderson, you know that I always

wished to die in this way.” He frequently asked, “Are the French

beaten?” And when told that they were, he exclaimed, “I hope the people

of England will be satisfied; I hope my country will do me justice.” He

spoke affectionately of his mother and his relatives, inquired after the

safety of his aides-de-camp, and even at that solemn moment mentioned

those officers whose merits had entitled them to promotion. He then

asked Major Colborne if the French were beaten; and on being told that

they were, on every point, he said, “It is a great satisfaction for me

to know we have beaten the French.” He thanked the surgeons for their

trouble. Captains Percy and Stanhope, two of his aides-de-camp, came

into the room, He spoke kindly to both, and asked if all his

aides-de-camp were well. After an interval he said, “Stanhope, remember

me to your sister.” This was the celebrated Lady Hester Stanhope, the

niece of Pitt. A few seconds after, he died without a struggle, January

16, 1809. The ramparts of the citadel of Corunna were selected as the

fittest place for his grave, and there he was buried at the hour of

midnight, “with his martial cloak around him.” The chaplain-general read

the funeral service of the Church of England by torch-light; and on the

succeeding day, when the British were safely out at sea, the guns of the

French paid the wonted military honours over the grave of the departed

hero. Soult afterwards raised a monument to his memory on the spot. A

marble monument has been erected to his memory in the Cathedral of

Glasgow. There is also an open air statue of him in George Square of the

same city. Another stands in St. Paul’s Cathedral, by order of

Parliament.

Sir John Moore had, with

one sister, who died unmarried in December 1842, four brothers, viz.,

1st, James Carrick Moore, Esq. of Corswall, Wigtonshire, author of a

“Narrative of the Campaign of the British Army in Spain, commanded by

Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore, authenticated by official papers and

original letters,’ London, 1809, 4to; also ‘The Life of

Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore, K.B.,’ London, 1834, 2 vols. 8vo. He

assumed, in 1821, the additional surname of Carrick, in compliance with

the testamentary injunction of his relative, Robert Carrick, a banker at

Glasgow, who bequeathed to him estates in the counties of Wigton,

Kirkcudbright, and Ayr.; 2d, Admiral Sir Graham Moore, C.B., whose son,

John Moore, held the rank of commander, R.N.; 3d, Charles Moore, of

Lincoln’s Inn, barrister at law, auditor of public accounts, who died

unmarried; and 4th, Francis Moore, at one time under secretary of war.

The latter married Frances, daughter of Sir William Twysden, baronet,

and relict of the eleventh earl of Eglinton, and by her had two sons,

William, a colonel in the army, and John, who died unmarried.

MOORE, DUGALD, a self-taught poet of conside4rable vigour of

imagination and expression, was born in Stockwell-street, Glasgow, in

August 1805. His father was a soldier in a Highland regiment, but died

early in life, leaving his mother in almost destitute circumstances.

While yet a mere child, Dugald was sent to serve as a tobacco-boy in a

tobacco-spinning establishment in his native city; an occupation at

which very young boys are often employed, at a paltry pittance, before

they are big enough to be apprenticed to other trades. He was taught to

read chiefly by his mother, and any education which he received at

schools was of the most trifling description. As he grew up, he was sent

to the establishment of Messrs. Lumsden and Son, booksellers, Queen

Street, Glasgow, to learn the business of a copper-plate pressman. Here

he was much employed in colouring maps. His poetical genius early

developed itself, and long before it was suspected by those around him,

he had blackened whole quires of paper with his effusions. Dugald found

his first patron in his employer, Mr. James Lumsden, afterwards provost

of Glasgow, who exerted himself successfully in securing for his first

publication a long list of subscribers among the respectable classes of

Glasgow. This work was entitled ‘The African and other Poems,’ and

appeared in 1829. In the following year Dugald published another volume,

entitled ‘Scenes from the Flood, the Tenth Plague, and other Poems;’ and

in 1831 he produced a volume larger and more elegant than the previous

ones, entitled ‘The Bridal Night, the First Poet, and other Poems.’ The

success of these several publications enabled their author to set up as

a bookseller and stationer in his native city, where he acquired a good

business. Dugald, indeed, may be cited as one of the few poets whose

love of the Muses, so far from injuring his business, absolutely

established and promoted it. IN 1833 he published ‘The Bard of the

North, a series of poetical Tales, illustrative of Highland Scenery and

Character;’ in 1835, ‘The Hour of Retribution, and other Poems;’ and in

1839, ‘The Devoted One, and other Poems.’ This completes the list of his

publications; but when it is considered that each, six in number, was of

considerable size, and contained a great number of pieces, it will be at

once acknowledged that his muse was in no ordinary degree prolific. Most

of his productions are marked by strength of conception, copiousness of

imagery, and facility of versification. Dugald Moore died, after s short

illness, of inflammation, January 2, 1841, while yet in the vigour of

manhood. He was never married, but resided all his life with his mother,

to whom he was much attached, and whom his exertions had secured in a

respectable competency. He was buried in the Necropolis of Glasgow,

where a monument was erected to his memory, from a subscription, raised

among his personal friends only, to the amount of one hundred pounds.

|