GALT,

a surname, meaning, in Gaelic, a stranger or travelled person.

GALT, JOHN,

an eminent novelist and prolific miscellaneous writer, was born at

Irvine in Ayrshire, May 2, 1779. He was the eldest son of a person

engaged in mercantile pursuits, and his parents ranked among the native

gentry. In the excellent schools of his native town he received the

first rudiments of his education. In his eleventh year the family

removed to Greenock, where he pursued his studies at the public school,

under Mr. Colin Lamont; and being addicted to reading, his inborn

passion for literature found ample gratification in the stores of a

public library to which he had access. Having a mechanical turn, with a

taste for music, he attempted the construction of a small pianoforte or

hurdy-gurdy, as well as of an Æolian harp. In these early years he

composed some pieces of music, one or two of which became popular. He

also conceived the idea of several local improvements of importance,

some of which were afterwards carried out.

In his boyhood

his health was delicate, and, like his great contemporary Sir Walter

Scott, he was considered a dull scholar. His strength and energy of

character, however, increased with his years, and in due time he was

placed in the counting-room of Messrs, James Miller and Co., with the

view of learning the mercantile profession. He continued in their

employment for several years; but having, in 1804, resented an insult

from a mercantile correspondent in a manner which rendered his situation

in Greenock very disagreeable, he was induced to remove to London, where

he embarked in trade in partnership with a Mr. M.Lachlan, but the

connexion ultimately proving unfortunate, was in the course of two or

three years dissolved, when he entered at Lincoln’s Inn, but eventually

abandoned the law. In 1809, on account of his health, he embarked for

the Mediterranean. At Gibraltar he made the acquaintance of Lord Byron

and Mr. Hobhouse, (created in 1851 Lord Broughton,) in whose company he

sailed to Sicily, whence he proceeded to Malta and Greece. At Tripolizza

he conceived a scheme for forming a mercantile establishment in the

Levant to counteract the Berlin and Milan decrees of Napoleon. After

touching at Smyrna, he returned to Malta, where, to his surprise, he

found that a plan similar to his had already been suggested to a

commercial company there by one of their partners resident in Vienna. He

now proceeded to inspect the coast of the Grecian Archipelago, and to

ascertain the safest route to the borders of Hungary; and after

satisfying himself of the practicability of introducing goods into the

Continent by this circuitous channel, he returned home in August 1811.

He made several applications to Government on the subject of his scheme,

but these were little attended to, and he never derived any benefit from

the project, which was soon afterwards acted upon by others to their

great advantage. The result of his observations he communicated to the

public in 1812, under the title of ‘Voyages and Travels in the years

1809, 1810, and 1811,’ which was his first avowed work, and contained

much new and interesting information relative to the countries he had

visited. He had previously published, about the end of 1804, a Gothic

poem, without his name, entitled ‘The Battle of Largs,’ which he

subsequently endeavoured to suppress.

Having been

appointed by Mr. Kirkman Finlay of Glasgow, joint superintendent of a

branch of his business established at Gibraltar, he went for a short

time to that place, where, however, his health suffered, and the

victories of the duke of Wellington in the Peninsula having seriously

checked the success of his mercantile operations, he resigned his

situation, and returned home for medical advice. Shortly after his

arrival in London he married Elizabeth, only daughter of Dr. Alexander

Tilloch, one of the proprietors and editor of the Star evening

newspaper, and editor of the Philosophical Magazine; by whom he had a

family.

Mr. Galt’s

next work, published about the same time as his Travels, was the ‘Life

and Administration of Cardinal Wolsey;’ and then followed in rapid

succession – ‘Reflections on Political and Commercial Subjects,’ 8vo,

1812; ‘Four Tragedies,’ 1812; ‘Letters from the Levant,’ 8vo, 1813; ‘The

Life and Studies of Benjamin West,’ 8vo, 1816; ‘The Majola, a Tale,’ 2

vols., 1816, which contains his peculiar opinions on fatality, founded

on an idea that many of the events of life depend upon instinct, and not

upon reason or accident; ‘Pictures from English, Scotch, and Irish

History,’ 2 vols, 12mo; ‘The Wandering Jew:’ ‘Modern Travels in Asia;’

‘The Crusade;’ ‘The Earthquake,’ 3 vols., and a number of minor

biographies and plays, most of the latter appearing in a periodical work

called at first the Rejected Theatre, and afterwards the New British

Theatre. Among other schemes of utility which about this time engaged

Mr. Galt’s attention was the establishment of the National Caledonian

Asylum, which owed its existence mainly to his exertions. In the year

1820 he contributed a series of articles, styled the ‘Ayrshire

Legatees,’ to Blackwood’s Magazine; these were afterwards collected into

a separate volume, which, from its admirable delineation of Scottish

life and character, became very popular, and established his name at

once as second only to that of the author of Waverley. Soon after

appeared ‘The Annals of the Parish,’ intended by the author as a kind of

Scottish Vicar of Wakefield, and it certainly possesses much of the

household humour and pathos of that admired work. About this period Mr.

Galt resided at Eskgrove House, near Musselburgh, having removed to

Scotland chiefly with a view to the education of his children. He next

published ‘The Provost,’ in one vol., which was considered by the author

his best novel; ‘The Steam Boat,’ 1 vol.; ‘Sir Andrew Wylie,’ 3 vols.;

‘The Entail,’ 3 vols.; and ‘The Gathering in the West,’ which last

related to the flocking of the West country people to Edinburgh at the

period of George the Fourth’s visit. The peculiarities of national

character, the quaintness of phrase and dialogue, the knowledge of life,

and the ‘pawky’ humour displayed in these works, rendered them unusually

attractive, and they were in consequence eagerly perused by the public.

A series of historical romances, in 3 vols. each, comprising ‘Ringan

Gilhaize,’ ‘The Spaewife,’ and ‘Rothelan,’ were published by Oliver and

Boyd, Edinburgh, but these were considered inferior to his other novels.

In 1824 he was

appointed acting manager and superintendent of the Canada Company, for

establishing emigrants and selling the crown lands in Upper Canada, a

situation which required his almost constant residence in that country,

and appears to have yielded him a salary of £1,000 a-year. Unfortunately

he soon got involved in disputes with the Government, having encountered

opposition to his plans from the governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland; and

his conduct being unfairly represented to the Directors at home, in 1827

he sent in his resignation to the chairman. He had in the meantime

founded, amidst many difficulties, the now flourishing town of Guelph,

on the spot where he had hewed down the first tree in that till then

uncultivated wilderness. Another town in the neighbourhood of Guelph was

named Galt, after himself, by his friend the Hon. William Dixon. He

returned to Lo9ndon in 1830, just previous to the breaking up of the

Canada Company, who seem to have treated him in a very harsh manner. At

a subsequent period he endeavoured, but without success, to form a New

Brunswick Company; and, besides various other schemes, he entertained a

project for making Glasgow a sea-port, by deepening the Clyde, and

erecting a dam, with a lock at Bowling Bay. This, which was a favourite

crotchet of his, he said was the legacy he left to Glasgow, in gratitude

for the many good offices done to him by the inhabitants of that city.

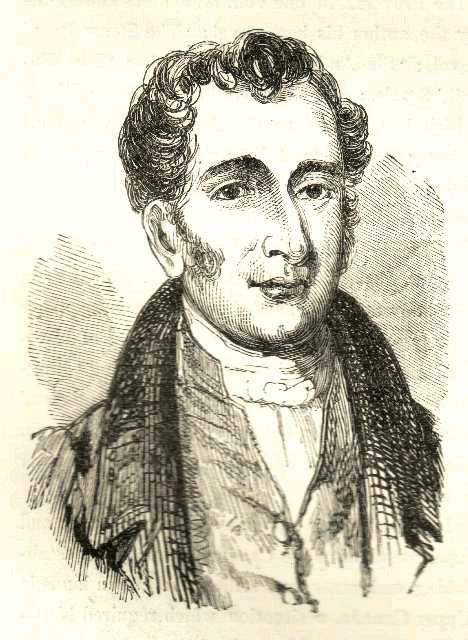

His portrait is subjoined.

[portrait of John Galt]

After his return to England he again had recourse to his pen for

support, and was for a short time editor of the Courier newspaper. Among

the principal of his works after this period may be particularly noticed

– ‘Lawrie Todd, a Tale,’ 3 vols., 1830, in which Mr. Galt gives the

fruits of his own experience in America as agent for the Canada Company;

‘Southennan, a Tale,’ in 3 vols., 1830, which embodied an antiquarian

description of Scottish manners in the reign of Queen Mary; ‘The Lives

of the Players,’ 2 vols, written for the National Library; ‘The Life of

Lord Byron,’ for the same series; “Bogle Corbet, or the Emigrants,’ 3

vols., 1831, intended as a guidebook to Canada; ‘Stanley Buxton, or the

School-fellows,’ 3 vols., 1832; ‘Eben Erskine,’ 3 vols.’ ‘The Stolen

Child,’ 1833; ‘Apotheosis of Sir Walter Scott;’ ‘The Member’ and ‘The

Radical,’ political tales, in one volume each.

In July 1832 Mr. Galt was struck with paralysis, and was removed to

Greenock, to reside among his relations. Although deprived of the use of

his limbs, and latterly unable to hold a pen, his mental powers retained

their vigour amid the decay of his physical energies. His memory, it is

true, was so far impaired that, some time previous to his death, he

required to finish any writing he attempted at one sitting, as he felt

himself at a loss, on returning to the subject, to recall the train of

his ideas, yet his mind was as active, and his imagination as lively as

ever; and the glee with which he either recounted or listened to any

humorous anecdote, showed that his keen sense of the ludicrous,

displayed to such advantage in his novels, had lost none of its

acuteness. In 1833 he published his ‘Autobiography,’ in 2 vols.’; and in

1834, his ‘Literary Life and Miscellanies,’ 3 vols. He also contributed

a variety of minor tales and sketches to the magazines and annuals.

Among his latest productions was a tale called ‘The Bedral,’ which was

not inferior to his Provost Pawkie; and ‘The Demon of Destiny, and other

Poems,’ privately printed at Greenock in 1839. His name appears as

editor on the third and fourth volumes of ‘The Diary Illustrative of the

Times of George IV.,’ a work which created considerable outcry on the

publication of the first and second volumes in 1838. Mr. Galt wrote in

all sixty volumes, and it would be difficult to furnish a complete list

of his works. In a list which he himself made he forgot an epic poem,

and he afterwards jocularly remarked that he should be remembered as one

who had published an epic poem, and forgot that he had sone so.

About ten days before his death he was visited by another paralytic

shock, being the fourteenth in succession. This deprived him at first of

the use of his speech, although he afterwards had power to articulate

indistinctly broken sentences. He was, however, quite sensible, and

indicated, by unequivocal signs, that he understood what was said to

him. He died April 11, 1839, leaving a widow and two sons. In person he

was uncommonly tall, and his form was muscular and powerful. He had

moved, during the greater part of his life, in the best circles of

society; and as his manners were frank and agreeable, he was ever a most

intelligent and pleasant companion. His feelings during the monotonous

latter years of his changeful life, which were varied only by his

sufferings, he expressed in the pathetic lines given in his

Autobiography, beginning –

“Helpless, forgotten, sad, and lame,

On one lone seat the livelong day,

I muse of youth, and dreams of fame,

And hopes and wishes all away.”