|

CAMPBELL,

a surname of great antiquity in Scotland, and of frequent occurrence in

Scottish history. It is stated by Pinkerton to have been derived from a

Norman knight, named de Campo Bello, who came to England with William the

Conqueror. As respects the latter part of the statement, it is to be

observed that in the list of all the knights who composed the army of the

Conqueror on the occasion of his invasion of England, and which is known

by the name of the Roll of Battle-Abbey, the name of Campo Bello is not to

be found. But it does not follow, as recent writers have assumed, that a

knight of that name may not have come over to England at a later period,

either of his reign or of that his successors. Mr. Pinkerton has

associated with this account of the origin of the name a theory that the

Campbells were not only not Celts but Goths, in which, however, he is

assuredly mistaken.

It has been

alleged in opposition to this account that in the oldest form of writing

the name, it is spelled Cambel or Kambel, and it is so found in many

ancient documents; but these were written by parties not acquainted with

the individuals whose name they record, as in the manuscript account of

the battle of Halidon Hill, by an unknown English writer, preserved in the

British museum; in the Ragman Roll, which was compiled by an English

clerk, and in Wyntoun’s Chronicle. There is no evidence, however, that at

any period it was written by any of the family otherwise than as Campbell, notwithstanding the extraordinary diversity that occurs in

the spelling of other names by their holders, as shown by Lord Lindsay in

the account of his clan, and the invariable employment of the letter p

by the Campbells themselves would be of itself a strong argument for the

southern origin of the name, did there not exist, in the record of the

parliament of Robert Bruce held in 1320, the name of the then head of the

family, entered as Sir Nigel de Campo Bello.

The writers,

however, who attempt to sustain the fabulous tales of the sennachies,

assign a very different origin to the name. It is personal, say they,

“like that of some others of the Highland clans, being composed of the

words cam, bent or arched, and beul, mouth; this having been

the most prominent feature o the great ancestor of the clan, Diarmid

O’Dwbin, or O’Dwin, a brave warrior celebrated in traditional story, who

was contemporary with the heroes of Ossian. In the Gaelic language his

descendants are called Siol Diarmid, the offspring or race of Diarmid.”

Besides the

manifest improbability of this origin on other grounds, two considerations

may be adverted to, each of them conclusive.

First, it is

known to all who have examined ancient genealogies, that among the Celtic

races personal distinctives never have become hereditary. Malcolm Canmore,

Donald Bane, Rob Roy, or Even Dhu, were,

with many other names, distinctive of personal qualities, but none of them

descended, or could do so, to the children of those who acquired them.

Secondly, it is

no less clear that, until after what is called the Saxon Conquest had been

completely effected, no hereditary surnames were in use among the Celts of

Scotland, nor by the chiefs of Norwegian descent who governed in Argyle

and the Isles. This circumstance is pointed out by Tytler in his remarks

upon the early population of Scotland, in the chapter in his second volume

of the History of Scotland. The domestic slaves attached to the

possessions of the church and of the barons have their genealogies

engrossed in ancient charters of conveyances and confirmation copied by

him. The names are all Celtic, but in no one instance does the son, even

when bearing a second or distinctive name, follow that of his father.

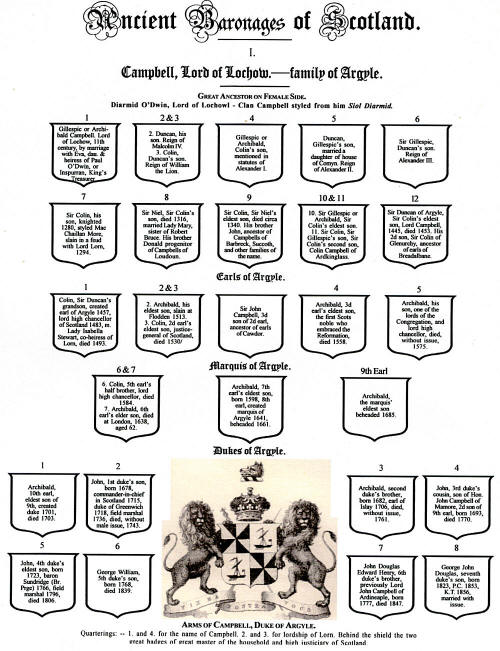

According to the

genealogists of the family of Argyle, their predecessors, on the female

side, were possessors of Lochow, in Argyleshire, as early as 404. In the

eleventh century, Gillespic (or Archibald) Campbell, a gentleman of

Anglo-Norman lineage, acquired the lordship of Lochow, by marriage with

Eva, daughter and heiress of Paul O’Dwin, lord of Lochow, denominated Paul

Insporran, from his being the king’s treasurer.

Sir Colin

Campbell of Lochow, sixth in descent from this personage, distinguished

himself by his warlike actions, and was knighted by King Alexander the

Third in 1280. In 1291 he was one of the nominees on the part of Robert

Bruce in the contest for the Scottish crown. He added largely to his

estates, and on account of his great prowess he obtained the surname of

More or great; from him the chief of the Argyle family is in Gaelic styled

Mac Chaillan More.

According to the

universally received opinion for several centuries, the distinctive Mac is

understood to imply son, or the son of, and Mac Chaillan would accordingly

imply the son of Chaillan. But it is not anywhere said or supposed that

Sir Colin’s father or any of his immediate ancestors bore the name of

Chaillan. He is described as Dominus Colinus Campbell Miles, filius

Dominus Gileaspec Camp-bel, in an acquisition referred to in a charter

of the monks of Newbattle abbey of the lands of Symontoun in Ayrshire, the

reddendo of which Sir Colin made over to that abbey in 1293. The father of

this Gillespic is said to have been Duncan Campbell, married to a lady of

the name of Sommerville, of the house of Carnwath, and the father of

Duncan, an Archibald Campbell, but there is no authentic instance of their

being styled of Lochow. Other instances occur where the prefix Mac is used

without signifying son, as, for example, in Macbeth, who is not known to

have been the son of Beth, and whose son Madoch did not bear that name;

and also in the genealogies of the Celtic slaves already referred to

quoted by Tytler in his history, where the word Mac occurs in the name of

a son which is not the same as that of his father. It is also found in

compound words, as Macpherson, Macfarquharson, &c., where the English word

son is also incorporated. We are therefore led to look for another

explanation of this frequent prefix. It is not found in Welsh names. In

the few Irish names in which it appears, a Scotch origin can frequently be

traced, and it is often used in the form of Mag, as Maguire, Maginnes, as

it is also along with the C in the Scotch names MacGlashan, MacGillivray,

&c. In the oldest Irish records the word Mic occurs, and is translated

son, and this mic is frequently found combined with Mac, as Mic Mac. There

is a curious instance in Irish history of the prefix Mac being employed to

signify great or big, as in a chief in the reign of Elizabeth, who is said

to have been called Mac Manus, great hand, from the length of his

arms. It is not therefore improbable that the word mac or mag may have

originally been a contraction of Magnus, great or big, employed in the

first instance by the priests, the only chroniclers and namegivers in the

corrupted Latin of those ages, either as an independent personal

distinctive, or to designate, among several of the same name, the

individual of greatest size and strength, and which in later ages, when

surnames came into use, might be continued by their descendants to

distinguish them from the children of others of the same name, on whom

such a personal distinctive had not been bestowed. It may be remarked,

that in this sense it sometimes occurs in British or Welsh, as well as in

Celtic or Irish, topography, as Mackinleith, the great place on the

Leath, a hundred and town of great antiquity in Montgomeryshire;

Maginnis, the great island, the ancient name of the peninsula

between Lough Strangford and Dundrum; also, corrupted into Muck or Mug, as

Mucross, the great cross; and in composition as Carrickmacross, the rock of the great cross.

It is probable that it has been used in

other countries in composition of names, as Magellan, or Magalhaen, the

great stranger, the name of the discoverer of Capt Horn.

On this

supposition also the word Mac Chaillan appears to be the Celtic

orthography, according to their pronunciation of Mag Allan, or Alaine, the

latter a word which is not only a frequent name in the Romance

language (with which the Norman-French, as spoken in Scotland in the

twelfth century is nearly identified), but was also used in that language

to signify what that word actually meant, viz., aleanus, stranger,

or alien, and Mac Caillane would thus imply the tall or large-bodied

stranger. The appellative mor or more, although frequently used in

modern Celtic, in a physical sense, as great, was in earlier times

more properly a distinctive of superior rank, as maormor, the ancient name

for the Pictish chiefs, viz., chief of the heads (maors, or mayors,

a corrupted Gotho-Latin term,) of the tribes. This term mor is

still preserved in the Spanish and Portuguese languages, which are

descended from the Romance, to express such a distinction of rank or

order, as alcayde mor, the head alcade; captain mor, head

captain, an officer equivalent to commander-in-chief of the military force

in Portuguese colonies; thesaureiro mor, head treasurer, &c. The

identity of many of the Romanceiro terms preserved in peninsular

languages, with those occurring in the earliest forms of Celtic words,

presents matter of speculation to the philologist and antiquary, but may

perhaps be accounted for by the earlier prevalence of that tongue and its

larger use also in the north of Scotland than even the Saxon itself, as

the conquerors under Canmore and his descendants were chiefly of that

race, and in mixing with the natives, they may have retained a number of

these Gotho-Latin terms whilst adopting along with them in the course of

that amalgamation, the general idiom of the conquered people.

It is therefore

suggested that the Celtic name Mac Ghaillan Mor, is in reality a compound

of corrupted Latin and Romance words implying the great or tall

stranger chief, a suggestion which singularly aids the opinion which,

after considerable attention to the matter, we have formed, viz. that the

first of the Campbells or Campobellos was a military knight, one of whose

ancestors may have assisted Alexander the Second in his conquest of

Argyle, and received, along with the Steward of Scotland, who obtained all

Bute and Cowal on the same occasion, the adjacent lands of Lochow as his

fee or reward, when these were forfeited by the rebellion or death of the

original possessor, probably receiving the hand of the daughter of the

latter as a further security for his acquisition. Whether this latter

circumstance occurred or not, it was not until a later age, when the

fourth earl of Argyle had acquired the jurisdiction over that region, that

the Norman bearing gyronny of eight for Campbell, came to be quartered in

the armorial bearings of the family, with the galley having furled sails,

oars in action, and flag and pendants flying for the lordship of the

Isles. The surrounding people, compelled to acquiesce in this arrangement,

would naturally describe a knight, or the son of a knight, so injected

into their midst, by the appellation of the great stranger chief.

In the account given of the origin of the name Campbell, by Jacob in his

English peerage, under their English title of Sundridge, vol. ii. p. 698,

London, 1767, there is a statement apparently contradictory of the

foregoing theory, viz., that the name Mac Chaillan, or as rendered by him

Mac Callan, is that of Sir Colin himself, “so called by the Irish.”

Admitting this to be the case, although its similarity is not apparent,

its only effect would be that instead of the great stranger chief, the distinctive Mac Caillan More would mean

Colin the great or tall

chief.

Sir Colin

Campbell had a quarrel with a powerful neighbour of his, the Lord of Lorn,

and after he had defeated him, pursuing the victory too eagerly, he was

slain (in 1294, according to Jacob in the account referred to) at a place

called the String of Cowal, where a great obelisk was erected over his

grave. This is said to have occasioned bitter feuds betwixt the houses of

Lochow and Lorn for a long period of years, which were put an end to by

the marriage of the daughter of Ergadia, the Celtic proprietor of Lorn,

with John Stewart of Innermeath about 1386. Sir Colin married a lady of

the name of Sinclair, by whom he had five sons.

Sir Niel

Campbell of Lochow, his eldest son, swore fealty to Edward the First, but

afterwards joined Robert the Bruce, and fought by his side in almost every

encounter, from the defeat at Methven to the victory at Bannockburn. King

Robert rewarded his services by giving him his sister, the Lady Mary

Bruce, in marriage, and conferring on him the lands forfeited by the earl

of Athol. Sir Niel, who was also styled Mac chaillan More, was one of the

commissioners sent to York in 1314, to negotiate a peace with the English.

His next brother Donald was the progenitor of the Campbells of Loudon.

[See LOUDON, earl of.] His three younger brothers, Dugal, Arthur, and

Duncan, all swore fealty to King Edward in 1296, but also became devoted

adherents of Robert the Bruce, and shared his favours. By his wife, the

Lady Mary Bruce, Sir Niel had three sons, Sir Colin; John, created earl of

Athol, upon the forfeiture of David de Strathbogie, the eleventh earl,

[see ATHOL, earl of,] and Dugal.

Sir Colin, the

eldest son, obtained a charter from his uncle, King Robert Bruce, of the

lands of Lochow and Ardscodniche, dated at Arbroath, 10th

February, 1316, in which he is designated Colinus filius Nigelli Cambel,

militis. In 1316, he accompanied King Robert to Ireland to assist in

placing his brother, Edward Bruce, on the throne of that kingdom. Sir

Colin assisted the steward of Scotland in 1334, in the surprise and

recovery of the castle of Dunoon, in Cowall, belonging to the Steward, but

held by the English and the adherents of Edward Baliol, and put all within

it to the sword, a feat which gave the first turn of fortune in favour of

King David Bruce. As a reward Sir Colin was made hereditary governor of

the castle of Dunoon, and had the grant of certain lands for the support

of his dignity. Syntoun states that it was his brother Dugal who did this

service, but Crawford has shown that this is wrong. Sir Colin died about

1340. By his wife, a daughter of the house of Lennox, he had three sons

and a daughter; namely, Sir Gillespic or Archibald; John, from whom the

Campbells of Barbreck and Succoth, and other families of the name, are

said to be descended; Dugal, who joined Edward Baliol, and in consequence

his estates in Cowal were forfeited by King David the Second, and given to

his eldest brother; and Alicia, married to Alan Lauder of Hatton.

The eldest son,

Sir Gillespic or Archibald, who added largely to the family possessions,

was twice married, first to a lady of the family of Menteith, and

secondly, to Mary, daughter of Sir John Lamont, and had a son, Sir Colin

Campbell of Lochow, who married Margaret second daughter of Sir John

Drummond of Stobhall, sister of Annabella, queen of Robert the Third. He

had three sons, Duncan, Colin, and David, and a daughter, married to

Duncan Macfarlane of Arrochar. Colin, the second son, was designed of

Ardkinglass, and of his family the Campbells of Ardentinny, Dunoon,

Carrick, Skipnish, Blythswood, Shawfield, Rachan, Auchwillan, and

Dergachie, are branches.

Sir Duncan

Campbell of Lochow, the eldest son, was one of the hostages in 1424, under

the name of Duncan lord of Argyle, for the payment of the sum of forth

thousand pounds (equivalent to four hundred thousand pounds of our money)

for the expense of King James the First’s maintenance during his long

imprisonment in England, when Sir Duncan was found to be worth fifteen

hundred merks a-year. He was the first of the family to assume the

designation of Argyle. By King James he was appointed one of his privy

council, and constituted his justiciary and lieutenant within the shire of

Argyle. He became a lord of parliament in 1445, under the title of Lord

Campbell. He died in 1453, and was buried at Kilmun. He married, first,

Marjory or Mariota Stewart, daughter of Robert duke of Albany, governor of

Scotland. In Pinkerton’s Scottish Gallery, there are portraits of both the

first Lord Campbell and his wife, of which the following are woodcuts:

[portraits of Lord

Campbell and his wife]

By

the first wife he had three sons, Celestine, who died before him;

Archibald, who also predeceased him, but left a son; and Colin, who was

the first of Glenorchy, and ancestor of the Breadalbane family, [see

BREADALBANE, earl and marquis of.] sir Duncan married, secondly, Margaret,

daughter of Sir John Stewart of Blackhall and Auchingown, natural son of

Robert the Third, by whom, also, he had three sons, namely, Duncan, who

according to Crawford, was the ancestor of the house of Auchinbreck, of

whom are the Campbells of Glencardel, Glensaddel, Kildurkland, Kilmorie,

Wester Keams, Kilberry, and Dana; Niel, progenitor, according to Crawford,

of the Campbells of Ellengreig and Ormadale; and Arthur or Archibald,

ancestor of the Campbells of Ottar, now extinct. It is said that the

Campbells of Auchinbreck and their cadets, also Ellengreig and Ormadale,

descend from this the youngest son, and not from his brother.

The first Lord Campbell was succeeded by his grandson Colin, the son of

his second son Archibald. He acquired part of the lordship of Campbell in

the parish of Dollar, by marrying the eldest of the three daughters of

John Stewart, third lord of Lorn and Innermeath. He did not, as is

generally stated, acquire by this marriage any part of the lordship of

Lorn (which passed to Walter, brother of John, the fourth Lord Innermeath,

and heir of entail), but obtained that lordship by exchange of the lands

of Baldoning and Innerdoning, &c. in Perthshire, with the said Walter. In

1457 he was created earl of Argyle. He was one of the commissioners for

negotiating a truce with King Edward the Fourth of England, in 1463, and

in 1465 was appointed, with Lord Boyd, justiciary of Scotland, which

office he filled for many years by himself after the fall of his

colleague. In 1470 he was created baron of Lorn, and in the following year

he was appointed one of the commissioners for settling the treaty of

alliance with King Edward the Fourth of England, by which James, prince of

Scotland, was affianced to Cecilia, Edward’s youngest daughter. He was

also one of the commissioners sent to France to renew the treaty with that

crown in 1484, and he eventually became lord-high-chancellor of Scotland.

In 1475 this nobleman was appointed to prosecute a decree of forfeiture

against John, earl of Ross and lord of the Isles, and in 1481 he received

a grant of many lands in Knapdale, along with the keeping of Castle Sweyn,

which had previously been held by the lord of the Isles. He died in 1493.

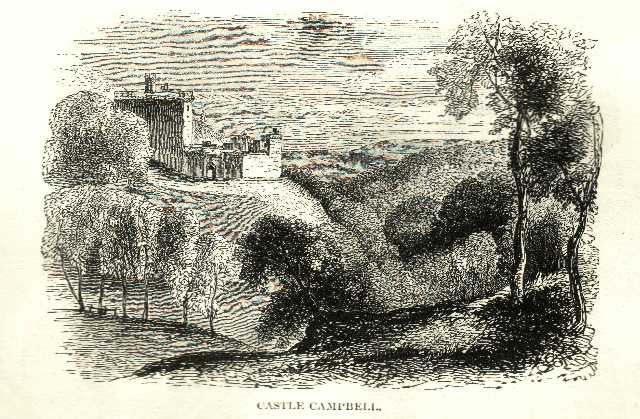

The manner in which the lordship of Campbell and Castle Campbell in the

parish of Dollar came into the possession of the family of Argyle, is

detailed in the New Statistical Account of Scotland with considerable

research, Isabella Stewart, supposed to be the eldest daughter of John

third Lord Innermeath, and first countess of Argyle, inherited about 1460

one-third of the lands of Dollar and Gloom, supposed to be the unentailed

portion of the estate of Innermeath, as heir-portioner with her two

sisters, – Margaret, married to Sir Colin Campbell of Glenorchie, ancestor

of the marquis of Breadalbane; and Marion, married to Arthur Campbell of

Ottar. The third belonging to Lady Campbell of Glenorchie, was ceded to

the Argyle family by her son Duncan in a deed of renunciation still

extant. How the third portion passed into the Argyle house does not

appear; but it is all included in a charter of confirmation by James the

Fourth of a charter by the bishop of Dunkeld, dated 11th May

1497. Muckartshill, a barony to the east of Dollar, appears about the same

period (1491) to have been feued by Shivaz bishop of St. Andrews to the

earl of Argyle. In 1489, by an act of the Scottish parliament the name of

Castle Gloom, its former designation, was changed to Castle Campbell. It

continued to be the frequent and favourite residence of the family till

1644, when it was burnt down by the Macleans in the army of the marquis of

Montrose, along with every house in Dollar and Muckart, – two houses only,

and these by mistake, escaping their savage fury. It was at Castle

Campbell that Knox tells us in his history he visited Archibald the fourth

earl of Argyle, and preached during successive days, to him and his noble

relatives and friends. Although never repaired, the castle and lordship of

Castle Campbell remained in the possession of the Argyle family till 1808,

when it was sold.

[woodcut of Castle

Campbell]

By

Isabel Stewart, his wife, eldest daughter of John, lord of lorn, the first

earl of Argyle had two sons and seven daughters. Archibald, his elder son,

became second earl, and Thomas, the younger, was the ancestor of the

Campbells of Lundie in Forfarshire. One of his daughters was married to

Angus the young lord of the Isles, and was believed by the islanders to

have been the mother of Angus’ son, Donald Dubh, who was imprisoned in the

castle of Inchconnell from his infancy. Another daughter was married to

Torquil Macleod of the Lewis. Having acquired the principal part of the

landed property of the two sisters of his wife, the first earl of Argyle

entered into a transaction with Walter Stewart, Lord Lorn, their uncle, on

whom the lordship of Lorn and barony of Innermeath, which stood limited to

heirs-male, had devolved, in consequence of which Walter resigned the

lordship of Lorn in favour of the earl of Argyle, who thereupon added the

style and designation of Lord to his other titles, Walter retaining the

barony of Innermeath, had the title of Lord Innermeath. [See ATHOL, earl

of.]

Archibald, second earl of Argyle, succeeded his father in 1493, and is

designed lord-high-chancellor of Scotland, in a charter to him by

Elizabeth Menteith, Lady Rusky, and Archibald Napier of Merchiston, her

son, of half of the lands of Inchirna, Rusky, &c., in the county of

Argyle, 28th June, 1494. The same year he had the office of

master of the household. Crawford, in his Peerage, page 17, says he was

lord-chamberlain in 1495, but his name does not occur as such in

Crawford’s Officers of State, and he is not designed lord-chamberlain in

any of the charters granted to him, which were numerous, under the great

seal, from 1494 to 1512. In 1499 he and others received a commission from

the king to let on lease, for the term of three years, the entire lordship

of the Isles as possessed by the last lord, both in the Isles and on the

mainland, excepting only the island of Isla, and the lands of North and

South Kintyre. He also received a commission of lieutenandry, with the

fullest powers, over the lordship of the Isles; and, some months later,

was appointed keeper of the castle of Tarbert, and bailie and governor of

the king’s lands in Knapdale. In 1504, when the insurrection of the

islanders under Donald Dubh, who had escaped from prison, broke out,

Argyle, with Huntly, Crawford and Marischal, the Lord Lovat, and other

powerful barons, were charged to lead the royal forces against the rebels;

but the insurrection was not finally suppressed till 1506. From this

period the great power formerly enjoyed by the earls of Ross, lords of the

Isles, was transferred to the earls of Argyle and Huntly; the former

having the chief rule in the south isles and adjacent coasts [Gregory’s

Highlands and Isles of Scotland.] At the fatal battle of Flodden, 9th

September 1513, his lordship and his brother-in-law, the earl of Lennox,

commanded the right wing of the royal army, and with King James the

Fourth, were both killed in that sanguinary engagement, so disastrous to

Scotland. By his wife, Lady Elizabeth Stewart, eldest daughter of John,

first earl of Lennox, he had four sons and five daughters. His eldest,

Colin, was the third earl of Argyle. Archibald, his second son, had a

charter of the lands of Skipnish, and the keeping of the castle thereof,

&c., 13th August 1511. His family ended in an heir-female in

the reign of Mary. Sir John Campbell, the third son, at first styled of

Lorn, and afterwards of Calder, married Muriella, daughter and heiress of

Sir John Calder of Calder, now Cawdor, near Nairn, as previously

mentioned. [See CALDER, surname of.]

According to tradition, she was captured in childhood by Sir John Campbell

and a party of the Campbells, while out with her nurse near Calder castle.

Her uncles pursued and overtook the division of the Campbells to whose

care she had been intrusted, and would have rescued her but for the

presence of mind of Campbell of Inverliver who, seeing their approach,

inverted a large camp kettle as if to conceal her, and commanding his

seven sons to defend it to the death, hurried on with his prize. The young

men were all slain, and when the Calders lifted up the kettle, no Muriella

was there. Meanwhile so much time had been gained that farther pursuit was

useless. The nurse, at the moment the child was seized, bit off a joint of

her little finger, in order to mark her identity – a precaution which

seems to have been necessary, from Campbell of Auchinbreck’s reply to one

who, in the midst of their congratulations on arriving safely in Argyle

with their charge, asked what was to be done should the child die before

she was marriageable? “She can never die,” said he, “as long as a

red-haired lassie can be found on either side of Lochawe!” From this it

would appear that the heiress of the Calders had red hair. The earl of

Cawdor is the representative of Sir John Campbell and his wife Muriella,

(see CAWDOR, earl of,) and the Campbells of Ardchattan, Airds, and Cluny

are their collateral descendants. Donald, the fourth son of the second

earl of Argyle, was abbot of Cupar, and ancestor of the Campbells of

Keithock in Forfarshire.

Colin

Campbell, the third earl of Argyle, was, immediately after his accession

to the earldom, appointed by the council to assemble an army and proceed

against Lauchlan Maclean of Dowart, and other Highland chieftains, who had

broken out into insurrection and proclaimed Sir Donald of Lochalsh lord of

the Isles. This he was enabled to do the more effectually, as in

anticipation of disturbances among the islanders, he had taken bonds of

fidelity from the vassals and others who had attached themselves to the

late earl his father. Owing to the powerful influence of Argyle, the

insurgents submitted to the regent, after strong measures had been adopted

against them; and, upon assurance of protection, he prevailed upon them to

appear at court, and arrange in person the terms of pardon and restoration

to favour; in consequence of which considerable progress seems to have

been made in the pacification of the Isles. Argyle and his followers took

out a remission for ravages committed by them in the isle of Bute in the

course of the insurrection, and rendered necessary, it may be supposed,

from some of the rebels having there found shelter and protection. In 1517

Sir Donald of Lochalsh again appeared in arms, but being deserted by his

principal leaders, he effected his escape. His two brothers, however, were

made prisoners by Maclean of Dowart and Macleod of Dunvegan, who had

submitted to the government. The services of the earl of Argyle had mainly

contributed to this state of matters in the Isles. He had, early in that

year, presented to the regent and council a petition, requesting “for the

honour of the realm and the commonweal in time coming,” that he should

receive a commission of lieutenandry over all the Isles and adjacent

mainland, on the grounds of the vast expense he had previously incurred,

of his ability to do good service in future, and of his having broken up

the confederacy of the islanders; which commission he obtained with

certain exceptions. He also claimed and obtained authority to receive into

the king’s favour, all the men of the Isles who should make their

submission to him and become bound for future good behaviour, by the

delivery of hostages and otherwise; the last condition being made

imperative, “because the men of the Isles are fickle of mind, and set but

little value upon their oaths and written obligations.” Sir Donald of the

Isles, his brothers, and the Clandonald were, however, specially excepted

from the benefit of this article. The earl likewise demand and received

express power to pursue and follow the rebels with fire and sword, to

expel them from the Isles, and to use his best endeavours to possess

himself of Sir Donald’s castle of Strone in Lochcarron [Gregory’s

Highlands and Isles of Scotland, pages 119, 120.] It would appear,

however, that Argyle’s services were not treated with that consideration

at the capital which he thought they were entitled to receive, as in 1519,

on his advice to the council that Sir Donald should be forfeited for high

treason, meeting with some opposition, he took a solemn protest before

parliament that neither he nor his heirs should be liable for any

mischiefs that might in future arise from rebellions in the Isles; as,

although he held the office of lieutenant, his advice was not taken as to

the management of the districts committed to his charge, neither had he

received certain supplies of men and money, formerly promised him by the

regent for carrying on the king’s service in the Isles.

In the

parliament which met at Edinburgh 25th February 1525, Argyle

was appointed one of the four governors of the kingdom, the duke of

Albany’s regency, from his continued absence in France, having been

declared at an end. In January 1526, he accompanied the young king, James

the Fifth, against the queen-mother and the rebel lords, and was a member

of the new secret council appointed in that year. For some years the Isles

had continued at peace, and Argyle employed this interval in extending his

influence among the chiefs, and in promoting the aggrandisement of his

family and clan, being assisted thereto by his brothers, Sir John Campbell

of Calder, so designed after his marriage with the heiress, and Archibald

Campbell of Skipnish. The former was particularly active. In 1527 an event

occurred which forms the groundwork of Joanna Baillie’s celebrated tragedy

of ‘The Family Legend,’ acted at the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, with great

success in 1810. It is thus related by Gregory: “Lauchlan Cattanach

Maclean of Dowart had married Lady Elizabeth Campbell, daughter of

Archibald, second earl of Argyle, and either from the circumstance of

their union being unfruitful or more probably owing to some domestic

quarrels, he determined to get rid of his wife. Some accounts say that she

had twice attempted her husband’s life; but, whatever the cause may have

been, Maclean, following the advice of two of his vassals, who exercised a

considerable influence over him from the tie of fosterage, caused his lady

to be exposed on a rock, which was only visible at low water, intending

that she should be swept away by the return of the tide. This rock lies

between the island of Lismore and the coast of Mull, and is still known by

the name of the ‘Lady’s Rock.’ From this perilous situation, the intended

victim was rescued by a boat accidentally passing, and conveyed to her

brother’s house. Her relations, although much exasperated against Maclean,

smothered their resentment for a time, but only to break out afterwards

with greater violence; for the laird of Dowart being in Edinburgh, was

surprised when in bed, and assassinated by Sir John Campbell of Calder,

the lady’s brother. The Macleans instantly took arms to revenge the death

of their chief, and the Campbells were not slow in preparing to follow up

the feud; but the government interfered, and, for the present, an appeal

to arms was avoided.” [Highlands and Isles of Scotland, p 128.]

On the

escape of the king, then in his seventeenth year, from the power of the

Douglases, in May 1528, Argyle was one of the first to join his majesty at

Stirling. He accompanied the king to Edinburgh on the 6th of

the following July, and on the confiscation of the vast estates of the

Douglas family, he obtained, 6th December 1528, a charter of

the barony of Abernethy, in Perthshire, forfeited by Archibald, earl of

Angus. The same year he was appointed lieutenant of the borders and warden

of the marches. On the refusal of the earl of Bothwell to lead the royal

army against the earl of Angus, who had appeared in arms, and repeatedly

defeated the king’s forces, the task of the expulsion of this formidable

rebel from Coldingham, where he had taken up his quarters, was committed

to the earl of Argyle, who, with the assistance of the Homes, compelled

him to fly into England, whence he did not return till after the death of

James. Argyle afterwards received an ample confirmation of the hereditary

sheriffship of Argyleshire and of the offices of justiciary of Scotland

and master of the household, by which these offices became hereditary in

his family. He had the commission of justice-general of Scotland renewed

25th October 1529. He died in 1530. In his last years he was

engaged in endeavouring to suppress a formidable insurrection in the South

Isles, headed by Alexander of Isla and the Macleans, who readily seized

the opportunity to revenge the death of their late chief. The combined

clans made descents upon Roseneath, Craignish, and other lands belonging

to the Campbells, which they ravaged with fire and sword, killing at the

same time many of the inhabitants.. The clan Campbell retaliated, by

laying waste great part of the aisles of Mull and Tiree and the lands of

Morvern. He had demanded extraordinary powers from the king to enable him

to reduce the Isles once more under the dominion of the law, but James

suspecting his motives, resolved upon trying conciliatory measures, and

offered pardon to any of the island chiefs who would submit to the

government, in which he was successful.

By his

countess, Lady Janet Gordon, eldest daughter of Alexander, third earl of

Huntly, the third earl of Argyle had three sons and a daughter, the latter

married, first, to James earl of Moray, natural son of King James the

fourth, and had a daughter; and, secondly, to John, tenth earl of

Sutherland, without issue. His sons were, Archibald, fourth earl of

Argyle; John, ancestor of the Campbells of Lochnell, of which house the

Campbells of Balerno and Stonefield are cadets; and Alexander, dean of

Moray.

Archibald, the fourth earl of Argyle, was, on his accession to the title

in 1530 (not 1533, as stated by Douglas in his Peerage as the date of his

father’s death) appointed to all the offices held by the two preceding

earls. In 1531 he commanded an expedition against the South Isles, while

the earl of Moray, natural brother of the king, proceeded against the

North Isles; but in both districts order was soon restored by the

voluntary submission of the insurgent chiefs. A suspicion had begun to be

entertained by some of the members of the privy council, which is said to

have been shared in by the king himself, that many of the disturbances in

the Isles were secretly fomented by the Argyle family, that they might

obtain possession of the estates forfeited by the chiefs thus driven into

rebellion, and an opportunity soon presented itself, which the king

eagerly availed himself of, to curb the increasing power of the earl of

Argyle in that remote portion of the kingdom. Finding that the timely

submission of Alexander of Isla, Maclean of Dowart, and the lesser chiefs,

placed them beyond his interference, the earl presented a complaint to the

council against the first of those named, charging him with various

crimes. Alexander being summoned to answer the charges made his appearance

at once; but Argyle absenting himself, the island chief gave in to the

council a written statement, denying the crimes laid to his charge, and

offering, if commission were given to himself or any other chief, for

calling out the array of the Isles, in the event of war with England, or

any part of the realm of Scotland, to bring more fighting men into the

field than Argyle, with all his influence, could levy in the Isles; also,

in case Argyle should be disposed at any time to resist the royal

authority, to cause the earl to quit his own country of Argyle, if he had

the king’s commands to that effect, and compel him to dwell in another

part of Scotland where “the king’s grace might get reason of him,” and

concluding by stating that the disturbed state of the Isles was mainly

caused by the late earl of Argyle and his brothers, Sir John Campbell of

Calder, and Archibald Campbell of Skipnish. In consequence of this appeal

of Alexander of Isla the king made such an examination into the complaints

of the islanders as satisfied him that the family of Argyle had been

acting more for their own benefit than for the welfare of the country, and

the earl was summoned before his sovereign to give an account of the

duties and rental of the Isles received by him, the result of which was

that James committed him to prison soon after his arrival at court. He was

soon liberated, but James was so much displeased with his conduct that he

deprived him of the offices he still held in the Isles, some of which were

bestowed on Alexander of Isla, whom he had accused. [Gregory’s

Highlands and Isles, page 141.] On Marcy 17, 1532, a remission was

granted to the earl and eighty-two others for their treasonable

fire-raising, with his standard unfurled, in the islands of Mull, Tiree,

and Morvern, as already stated in the end of the notice of his father. In

August 1541, five thousand pounds were given to him out of the king’s

treasury, on his resignation of Makane’s lands in the isles to the crown.

In a charter to him of the king’s lands of Cardross in Dumbartonshire,

dated 28th April 1542, he is designed master of the king’s

wine-cellar, “cellae regis vinariae magister.” After the death of James

the Fifth he appears to have regained his authority over the Isles, having

appeared in arms there, at the head of several of the clans, the earl

prepared to defend his insular acquisitions; but in 1543 Donald, with a

force of fifteen hundred men, invaded Argyle’s territories, slew many of

his vassals, and carried off a great quantity of plunder. Argyle was one

of the peers who, in July of that year, entered into an association to

oppose the marriage of the young queen Mary and the youthful prince

Edward, afterwards King Edward the Sixth of England, and the consequent

union of the two crowns, “as tending to the high dishonour, perpetual

skaith, damage and ruin of the liberty and nobleness of the realm.” In

1544 an expedition was sent by Henry the Eighth to aid the earl of Lennox

in his claim to the regency, to harass the coasts of Scotland, and thus

put down the opposition to the proposed royal marriage. An attempt on the

part of the earl of Lennox, who was in the command of the English forces,

with eighteen vessels of war and eight hundred men, to seize the castle of

Dumbarton failed, and on his ships passing down the Clyde they were fired

at by the earl of Argyle, who, with a large body of his vassals, and some

pieces of artillery, had taken post at the castle of Dunoon. On his

arrival at Bute, Lennox determined to attack Argyle in turn. the latter,

with seven hundred men, attempted to oppose the landing of Lennox’s troops

at Dunoon, but was unable to withstand the superior artillery of the

English vessels. After a skirmish in which Argyle lost eighty men, many of

them gentlemen, the village of Dunoon was burnt and plundered by the

invaders, Argyle sustaining further loss in attempting to harass their

retreat. Four or five days thereafter Lennox, with five hundred men,

landed in another part of Argyle, and laid waste the surrounding country.

At the disastrous battle of Pinkie, 10th Sept. 1547, the earl

of Argyle had the command of a large body of Highlanders and Islanders,

and he also distinguished himself at the siege of Haddington in the

following year. In June 1555 a commission was given to the earls of Argyle

and Athole over the Isles, and on the queen regent (Mary of Guise)

proceeding to the north, in July 1556, to hold justice-courts for the

punishment of great offenders, the earl of Argyle was one of those who

accompanied her. He was the first of the Scots nobles who embraced the

principles of the Reformation, and employed as his domestic chaplain, Mr.

John Douglas, a converted Carmelite friar, who preached publicly in his

house. the archbishop of St. Andrews in a letter to the earl, endeavoured

to induce him to dismiss Douglas, and return to the Romish church, but in

vain, and on his death-bed he recommended the support of the new doctrines

and the suppression of Popish superstitions to his son. He died in August

1558. He was twice married. By his first wife, Lady Helen Hamilton, eldest

daughter of James first earl of Arran, he had a son, Archibald, fifth earl

of Argyle. His second wife was Lady Mary Graham, only daughter of William,

third earl of Menteith, by whom he had Colin, sixth earl, and two

daughters. Lady Margaret Campbell, the elder daughter married James Lord

Down, ancestor of the earls of Moray. Lady Janet, the younger, became the

wife of Hector Maclean of Dowart; Gregory says of James Macdonald of Isla,

the great rival of the Argyle family in the Isles.

Archibald, fifth earl of Argyle, was educated under the direction of Mr.

John Douglas, his father’s domestic chaplain and the first protestant

archbishop of St. Andrews, and distinguished himself as one of the most

able among the Lords of the Congregation. In December 1557, when styled

lord of Lorn, with his father and the earls of Glencairn and Morton,

Erskine of Dun, and other leading reformers, he had subscribed at

Edinburgh the first bond entered into in Scotland for the support of the

gospel and the maintenance of faithful ministers, but for some time he

adhered to the party of the queen-mother. In November 1558, soon after his

accession to the title, he and Lord James Stuart, prior of St. Andrews,

afterwards the regent Moray, – the one, as Douglas remarks, the most

powerful, and the other the most popular leader of the protestant party, –

were appointed to go to Paris, with the crown and other ensigns of

royalty, to crown Francis, dauphin of France, as king of Scotland, on his

marriage with the young Queen Mary; “that they, being employed abroad,

matters of greater importance, namely anent religion, might be overturned

at home in their absence. The consideration of the death of Mary, queen of

England, who ended her life the seventeenth day of this same month of

November, stayed them altogether; for it was thought that the queen and

her husband the king, would assume to themselves greater titles.” [Calderwood,

vol. i. page 422.] And indeed Francis and Mary did soon after assume

the title of king and queen of England, as well as of Scotland and France.

On the

occurrence of the memorable riot at Perth, in May 1559, when the “rascal

multitude,” as Knox called them, after destroying the popish altars and

images, proceeded to level with the ground several of the monasteries and

other religious houses, the queen regent, then at Stirling, enraged at the

tumult, hastened to Perth, at the head of seven thousand men, chiefly

French auxiliaries commanded by D’Oysel, with the purpose of inflicting

signal vengeance on the inhabitants. By deceitful promises she had induced

the protestant leaders to dismiss their armed followers, and she hoped to

surprise the town before any new or effective force could be collected to

oppose her; but, on reaching the neighbourhood of Perth, she found that

the Reformers had assembled from all parts to the assistance of their

friends. The gentlemen of Fife, Angus, and Mearns, with their followers,

had formed a camp near Perth, where they were speedily joined by the earl

of Glencairn, with two thousand five hundred men from the west country.

Instead, therefore, of attacking the town, the regent sent the earl of

Argyle and the Lord James Stuart, to enter into a negotiation with the

protestant leaders, having, with her usual duplicity, persuaded these two

noblemen, reformers themselves, that the reformation of religion was a

mere pretence with those who opposed her authority, and that they meant

nothing but rebellion. Ultimately, on the 28th of May, a treaty

was concluded, principally through the means of the earl and the Lord

James Stuart, whereby it was agreed that the two armies should return

peaceably to their homes, that the town of Perth should be evacuated by

the protestant party and the queen regent allowed to enter it; that no

molestation should be given to those in arms, nor to the protestants

generally, that no French garrison should be stationed in Perth, that no

Frenchman should come nearer that city than three miles, and that in the

approaching assembly of the three estates, the work of the reformation

should be finally established. The leaders of the Congregation subscribed

this agreement, but under strong apprehensions that it would not be

adhered to, and before they separated, a new bond was entered into for the

defence of each other and the maintenance of the true religion, which was

signed by Argyle, the Lord James Stuart, the earl of Glencairn, Lords Boyd

and Ochiltree, and Mathew Campbell of Taringhame. As they feared, the

regent very soon violated the treaty. She entered Perth on the 29th,

attended by French soldiers, some of whom, firing their hackbuts on the

stair of Patrick Murray, who was known to be a reformer, killed his son, a

boy about twelve years of age. This being told to the regent, she said in

mockery, “It is pity it chanced on the son, and not on the father; but

seeing it hath so chanced, me cannot be against fortune.” the inhabitants

generally were harassed with every kind of outrage, and not only were the

magistrates dismissed and creatures of her own put in their place, but the

popish service was restored, with all its rites and ceremonies. On being

remonstrated with on this infraction of the treaty, she answered that she

was not bound to keep faith with heretics, and that “princes were not to

be strictly held to their promises;” adding, “I myself would make little

conscience to take from all that sort their lives and inheritances, if I

might do it with as honest an excuse.” Disgusted at her perfidy, and

having no further confidence in her word, the earl of Argyle and the Lord

James Stuart deserted the queen regent, and at once went over to the

Congregation, as the great body of the reformers were called, with whom

their sympathies had been all along. The queen sent a charge to them,

under the pain of her highest displeasure to return, but they answered

that with safe consciences they could not. When she departed from Perth

she left in it a garrison of four hundred soldiers.

In the

meantime the earl of Argyle and the lord James Stuart proceeded to St.

Andrews, and on the way sent missives to Erskine of Dun, the laird of

Pittarrow, Halyburton, provost of Dundee, and other leading reformers, to

meet them in that city, on the 4th of June, to take measures

for the promotion of the Reformation. John Knox, after preaching at Cupar

in Fife, at Crail, and at Anstruther, in all which places, as at Perth,

the people had demolished the altars, the images, and all other monuments

of idolatry, proceeded to St. Andrews, where he had agreed to meet the

earl of Argyle and Lord James Stuart. the popish archbishop came to the

town, accompanied with a hundred soldiers, and sent a message that if Knox

offered to preach in his cathedral church, he would have him shot with a

dozen hackbuts; his friends, anxious for his safety, endeavoured to

dissuade him from preaching, but he would not be prevented. The subject of

his discourse was the ejection of the buyers and sellers from the temple,

which “the provost and bailies with the commonality” of the town applied

to the circumstances of the times, and straightway proceeded to pull down

and destroy their splendid cathedral, with the other churches, razing the

monasteries of the Black and Grey friars to the ground, and destroying all

the monuments of antiquity within the city. The archbishop hastened to

Falkland, where the regent was, with her French troops, and gave her the

first intimation of the outrages that had been committed. The regent

immediately issued a proclamation summoning her troops and adherents to

assemble at Cupar next day. The lords of the Congregation, on their part,

despatched earnest representations to their friends for assistance, and

though only attended by a hundred cavalry and the same number of infantry,

instantly marched for Cupar. Their adherents hastened to their aid, and by

the following morning they were joined by an army of three thousand men.

Lord Ruthven brought some horsemen to them from Perth; the earl of Rothes,

hereditary sheriff of Fife, also came with a goodly company; the towns of

St. Andrews and Dundee sent their most effective men, and Cupar poured

forth its population, to defend itself and aid the general cause. The army

of the regent, on the morning of the 13th June, encamped upon

an eminence in the neighbourhood of Cupar, called the Garliebank. It

consisted of two thousand Frenchmen under General D’Oysel, and about one

thousand Scots under the duke of Chatelherault, (Lord Hamilton, second

earl of Arran.) The troops of the Congregation, the command of which had

been assigned to Halyburton, provost of Dundee, were stationed on the high

ground called Cupar muir, to the west of the town, and their ordnance was

so posted as to command the surrounding country. Astonished both at the

strength of their opponents and the skilfully-selected position which they

occupied, and from which, by twice feigning a retreat, they endeavoured in

vain to draw them, and knowing that they could not depend on the Scots in

their own ranks, should a battle take place, the commanders of the royal

forces recommended to the regent, who had remained at Falkland, to enter

into a negotiation with the lords of the Congregation. Yielding to

necessity, she consented, and a truce for eight days was, after

considerable discussion, agreed upon between the duke of Chatelherault and

D’Oysel, for the regent, and the earl of Argyle and the Lord James Stuart

for the Congregation, on condition that the French troops should

immediately be transported to Lothian, and that the regent should send

certain noblemen to St. Andrews, to adjust finally the articles of an

effectual peace. The lords of the Congregation then dismissed their

troops, and retired to St. Andrews; but though the regent so far kept her

word as to send her French troops and artillery across the Forth, the

reformers waited in vain for the appearance of her commissioners. At this

time, in a letter form the earl of Argyle and the Lord James Stuart, the

regent was respectfully but earnestly entreated to withdraw the garrison

which she had left at Perth, but no attention was paid to their request.

It was, therefore, resolved to expel the garrison by force. The lords of

the Congregation again appeared in arms at the head of their followers,

and on the 24th of June marched upon Perth. The earl of Huntly,

chancellor of the kingdom, with the Lord Erskine, and Mr. John Bannatyne,

justice-clerk, hastened to entreat the lords to delay besieging the town

for a few days. They were told that it would not be delayed even for an

hour, and that if one single protestant should be killed in the assault,

the garrison should be put indiscriminately to the sword. The garrison

were twice summoned to surrender, but as they refused to do so, the

batteries of the Congregation were opened upon the town; and on the 26th

of June, the garrison capitulated. The burning of the royal palace and

abbey of Scoon followed. The earl of Argyle and Lord James Stuart, with

Knox and the provost of Dundee, exerted themselves to save them, but in

vain. Being apprized that the regent intended to seize and garrison

Stirling castle, and to fortify the bridge over the Forth, so as to

prevent their passage, the earl and the lord James Stuart left Perth at

midnight, and appeared at Stirling, with their forces, in the morning. On

this occasion they were accompanied by three hundred inhabitants of Perth,

who had joined the standard of the Congregation, and to indicate their

zeal and resolution they wore ropes about their necks, that they might be

ignominiously hung with them if they deserted their colours. A picture of

the march of this resolute body is still preserved in Perth, and the

circumstance of their substituting ropes for neckerchiefs or ribbons is

the subject of the popular allusion to “St. Johnstone tippets.”

The two

convents of the Black and Grey friars of Stirling and the venerable abbey

at Cambuskenneth in its neighbourhood, were laid in ruins, and after

remaining three days at Stirling, the army of the Congregation on the

fourth proceeded to Linlithgow, where they destroyed the churches and

monastic houses. The earl of Argyle and the lord James Stuart then

directed their march upon Edinburgh, which they entered on the 29th

of June, on which the regent retreated to Dunbar. the force which the

confederates had with them was not very great, but wherever they went they

were joined by the populace, and the popish party were so effectually

daunted that they could make no head against them. The efforts of the

magistrates to preserve the churches and religious houses of the capital

were energetic, but they were in vain. Upon the first rumour of the

approach of the earl of Argyle, the mob attacked both the monasteries of

the Black and Grey friars, and left nothing but the bare walls standing.

when the earl entered the capital they proceeded to still further

“purification.” Trinity college church and its prebendal buildings were

assailed and some parts of them pulled down. The altars in St. Giles’

church and St. Mary’s or the Kirk of Field, were removed, and the images

destroyed or burnt. At Holyrood abbey also the altars were overthrown, and

the church otherwise defaced. Preachers were, at the same time, appointed

to expound to the people the pure gospel. The mint, with the instruments

for coining, was seized, as the stamping of base money had raised the

price of the necessaries of life; but though it was alleged against them

that they had possessed themselves of large sums of money, this does not

appear to have been the case.

During

these proceedings, the regent issued a proclamation against the

Congregation, declaring that under the pretence of religion they sought to

overturn the government, commanding them to leave Edinburgh in six hours,

and enjoining all good subjects to avoid their society under the pain of

treason. This proclamation had its effect to a certain extent, as many of

the Congregation retired to their homes. The lords, in a letter to the

queen regent, dated 2d July (1559) were careful to exculpate themselves

from the charges brought against them, and offered to explain all their

views and wishes in presence of the regent, if they were permitted free

access to her. After several communings, the regent requested that the

earl of Argyle and the Lord James Stuart might be sent to her; but as some

treachery was suspected, it was deemed expedient that they should not go

near her. The duke of Chatelherault had been persuaded that the object of

the Congregation was to deprive Mary of her crown, and also the duke and

his heirs of their right of succession; but in a proclamation thy showed,

as the preachers did in their sermons, that their real motive was the

reformation of religion and complete liberty of conscience. Recourse was

then had to negotiations, and after a conference at Preston, which led to

no result, the queen dowager left Dunbar, and with her troops took

possession of Leith, and approached within two miles of Edinburgh. On

being informed by the governor of the castle (Lord Erskine) that he would

fire if her entrance was opposed, a treaty was entered into, on the 25th

July, by which the Congregation agreed that the town of Edinburgh should

be open to the regent; that Holyroodhouse, the mint, and the instruments

of coinage should be delivered up to her; and that they should be obedient

to her authority and the laws, and should abstain from injuring the

papists, or employing violence against the churches or religious houses,

till the 10th of the ensuing January, when a parliament was to

meet. The regent, on her part, agreed that the inhabitants of Edinburgh

should adopt what religion they thought proper; that their preachers would

not be molested, nor themselves troubled in their persons or their goods;

that no French garrison or Scottish mercenaries should be stationed within

the city; and that, in other places of the kingdom, similar toleration

should be given to the protestants and their preachers. These conditions

Chatelherault and Huntly, at a subsequent private interview with the lords

of the Congregation, held at the Quarry Holes near Calton Hill, declared

their resolution to see observed, or else to leave the queen dowager’s

party. On the following day the lords of the Congregation left Edinburgh

and proceeded to Stirling, where they held a council, and on the first of

August entered into a third league or bond for mutual defence.

When at

Glasgow, on his return to his own district, Argyle and Stuart received an

invitation from the duke of Chatelherault, to visit him at Hamilton, where

they remained a night, and met the duke’s eldest son, the earl of Arran,

newly arrived from Paris, having escaped death or imprisonment from the

Guises on account of his protestant principles [See HAMILTON, duke of.]

The duke had become dissatisfied with the violent and arbitrary measures

of the queen regent, and convinced of her perfidy, he and Arran, his son,

had now resolved upon joining the lords of the Congregation. Arran

accordingly, on the 10th of September, accompanied Argyle and

Lord James Stuart to a convention of the lords of the Congregation held at

Stirling, which resulted in the principal chiefs accompanying these two

lords in a second visit to the residence of the duke, there to mature

their further proceedings, of which the convention entered into shortly

thereafter, for the entrance of English troops into Scotland, was the most

important.

In the

subsequent transactions the earl of Argyle acted a principal part. When,

at the commencement of the siege of Leith, on the last day of October

1559, the French soldiers, in a sally from the fort, drove the troops of

the Congregation back to Edinburgh, after capturing their ordnance, and

pursued them to the middle of the Canongate and up Leith Wynd, Argyle,

with his Highlanders, was the first to stop the flight, and give a check

to the pursuers. His name appears the fifth of the noblemen who signed the

Contract of Berwick, which led to the introduction of the English army,

under the Lord Grey, to the assistance of the Congregation, and the

expulsion of the French from Scotland. In this Contract occurs the

following clause personal to the earl: “And also, the erle of Argile, lord

justice of Scotland, being presentilie joyned with the said duke (of

Chatelherault) sall imploy his force and good will where he sall be

required by the queen’s majestie (Elizabeth) to reduce the north parts of

Ireland to the perfyte obedience of England, conforme to a mutuall and

reciprock contract to be made betwixt her majestie’s lieutenant or deputie

of Ireland, being for the time, and the said erle, wherin sall be

conteaned what he sall doe for his part, and what the said lieutenant and

deputie sall doe for his support, iom case he sall have to doe with James

Makconneill, or anie other of the iles of Scotland, or realme of Ireland.”

The Makconnel here referred to is supposed to be a miswriting for James

Macdonald of Isla, who had been stirred up by the queen regent to attack

the lands of Argyle. For performance of his part of this contract Argyle

gave as a hostage his cousin Colin Campbell. On the 27th of

April, the lords of the Congregation entered into a fourth bond, for their

mutual protection and assistance, and in this they were joined by the earl

of Huntly, who had hitherto opposed their proceedings.

On the

10th of June 1560, the queen regent died in the castle of

Edinburgh, which put an end to hostilities for the time. Before her death

she expressed to Argyle and other lords, in an interview she asked with

them, her deep regret for her conduct, which she attributed to the

counsels of her relatives on the continent. The earl of Argyle’s name

appears the third of the nobility who subscribed the First Book of

Discipline; and soon after, when the lords passed an act that all

remaining monuments of idolatry should be destroyed, he was ordered with

the earl of Glencairn to assist the earl of Arran in the west in seeing

this done in that district.

The earl

of Argyle was of the cortege that received Queen Mary on her landing at

Leith 19th August 1561. He was immediately thereafter sworn a

privy councillor. Early in 1562 he was one of the lords engaged in making

provision for the ministers, against the inadequacy of which Knox

appealed. On the 13th of September, the queen went to Stirling,

and on the Sabbath a riot took place in that town, in consequence of an

attempt being made to perform mass. “The earl of Argyle,” says Randolph,

the English ambassador, in a letter to Cecil, “and the lord James Stuart

so disturbed the quire that some, both priests and clerks, left their

places with broken heads and bloody ears.” On the 26th May

1563, the queen opened parliament with extraordinary splendour. On this

occasion the duke of Chatelherault carried the crown, Argyle the sceptre,

and Moray the sword.

The earl

had married Jean, natural daughter of King James the Fifth by Elizabeth

daughter of John Lord Carmichael, but he does not seem to have lived on

very happy terms with her, as we find that John Knox had been employed, on

more occasions than one, to reconcile them after some domestic quarrels.

In 1563, at the third conference between Queen Mary and Knox, her majesty

requested him again to use his good offices on behalf of her sister, the

Lady Argyle, who, she confessed, was not so circumspect in everything as

she could wish; “yet,” she added, “her husband faileth in many things.” “I

brought them to concord,” said Knox, “that her friends were fully content;

and she promised before them she should never complain to any creature,

till I should first be made acquainted with the quarrel, either out of her

own mouth, or by an assured messenger.” “Well,” said the queen, “it is

worse than your believe. Do this much for my sake, as once again to

reconcile them, and if she behave not herself as becometh, she shall find

no favour of me; but in no case let my lord know that I employed you.”

Knox, in consequence, wrote to the earl on the countess’s behalf,

exhorting him “to bear with the imperfections of his wife, seeing that he

was not able to convince her of any crime since the last reconciliation,

but his letter was not well received.” [Calderwood, vol. ii. p.

215.] Her majesty passed the summer of the same year at the earl’s house

in Argyleshire, in the amusement of deer-hunting.

His

lordship was against the marriage of the queen with Lord Darnley, and in

the midst of the preparations for that ill-fated union, he and the earl of

Moray appeared at Edinburgh with a body of five thousand horsemen,

ostensibly for the purpose of attending a court to which the earl of

Bothwell had been cited, but really, as the queen considered, more to

overawe herself than to frighten that nobleman. She, therefore, ordered

the justice-clerk to adjourn the court. Two months previous to the

marriage, she created Darnley earl of Ross, when the duke of Chatelherault,

and the earls of Argyle, Moray, and Glencairn, immediately retired from

the court, and began to concert measures for opposing the match by force

of arms. After the marriage, when the discontented lords took refuge in

England, the earl retired to Argyle, but after the murder of Rizzio, on

the 9th of March 1566 (the countess of Argyle being then with

the queen at supper), the banished lords were received into favour, and

the processes of treason against them discharged. In the ensuing April the

queen sent for the earls of Argyle and Moray, and reconciled them to the

earls of Huntly, Bothwell, and Athole; and in June, when her majesty went

to the castle of Edinburgh to be confined of James the Sixth, she ordered

lodgings to be provided for the earl next her own, probably that her

sister the countess might be near her. His lordship, however, was not

present at the baptism of the young prince in Stirling castle, on account

of the popish ceremonies, but his countess stood sponsor for Queen

Elizabeth, and held the child at the font.

The earl

of Argyle’s name appears second on the famous bond subscribed by some of

the nobility in favour of the queen’s marriage with Bothwell, and the

ratification of it afterwards signed by the queen was committed to his

care, in case her majesty should repent of the match. At this time he

seems to have played a double part. On the marriage taking place, he was

one of the noblemen who entered into the bond of association for the

defence of the young prince, but the day after he revealed all their

designs to the queen. He carried the sword of state at the coronation of

James the Sixth, 29th July 1567, and attended the convention at

Edinburgh the 15th August, at which the regency of the earl of

Moray was confirmed. In the General Assembly which met in the following

December the earl and his countess were censured, he for separation from

his wife, although he alleged that the blame was not in him, and she for

assisting at the baptism of the king “in papistical manner.” Afterwards,

deeming the queen very ill used in being kept a prisoner, he entered into

the association for procuring her liberty on reasonable conditions, and

signed the bond to that effect 8th May 1568. He was created her

lieutenant, and was chief commander of her forces at Langside on the 13th

of the same month; but just as the hostile armies were about to take their

ground, he was seized with an apoplectic fit, which delayed the advance of

Mary’s troops and contributed not a little to her defeat. After this he

retired to Dunoon, and refused to submit to the regency of his old friend

and confederate the earl of Moray, but twice appeared in arms at Glasgow,

to concert measures with the Hamiltons for the restoration of Mary. He was

in consequence summoned to St. Andrews in the following April, when he

took an oath to remain quiet, and made his peace on easy terms.

On the

assassination of the regent Moray, Argyle and other noblemen of the

queen’s party assembled at Linlithgow, 10th April 1570, and

with the duke of Chatelherault and the earl of Huntly, was constituted her

majesty’s lieutenant in Scotland. In 1571 he was prevailed on by the

regent Lennox to submit to the king’s authority, and to appear in the

parliament at Stirling in September of that year. Lennox being murdered on

the 4th of that month, Argyle was a candidate for the regency,

but the choice fell on the earl of Mar, and Argyle was sworn a privy

councillor. On Morton becoming regent in November 1572, Argyle was

appointed lord-high-chancellor, and on the 17th January 1573 he

obtained a charter under the great seal of that office for life. That same

day he carried the sceptre, on the regent going in state to the low

council house of Edinburgh, to choose the Lords of the Articles. He died

of the stone, 12th September 1575, aged about 43, and is

celebrated by Johnston in his Heroes. His countess, Queen Mary’s half

sister, having died without issue, was buried in the royal vault in the

abbey of Holyroodhouse; and he married, a second time, Lady Johanna or

Joneta Cunningham, second daughter of Alexander fifth earl of Glencairn,

but as she also had no children, he was succeeded in his estates and

titles by his brother.

Colin,

sixth earl of Argyle, previous to succeeding to the earldom was styled Sir

Colin Campbell of Boquhan. He early engaged in the quarrel against the

regent Morton, arising out of the following circumstances: In 1576, as

hereditary justice-general of Scotland he claimed that a commission of

justiciary, formerly given by Queen Mary to the earl of Athole over the

territory of the latter, should be annulled. This Athole resisted, and not

only refused to surrender for trial two of the Athole Stewarts against

whom Argyle alleged various crimes, but seized two of the Camerons charged

with the murder of the late chief of that clan, whom he detained in

prison, although claimed by Argyle as his vassals. The two earls collected

their retainers in arms, to settle the dispute between them in the field,

when the regent interposed, and obliged them to disband their forces.

Having obtained secret information that Morton intended to prosecute them

for treason, they agreed to forget their private quarrels, and unite for

mutual defence. They disregarded the citation of the regent to appear

before a court of justice, and as he dreaded their joint power, he was

forced unwillingly to abandon his project. In the end of the following

year the earl of Argyle was still farther incensed against Morton, by his

sending for the jewel called the H, because the precious stones were set

in the form of that letter, signifying Henrie, and which it was supposed

had been given by Queen Mary to her sister the late countess of Argyle. He

was not inclined to comply with the request, but on being charged by an

officer to deliver it up, as it belonged to the king, he at once resigned

it. About this time the laird of Glengarry presented a petition to the

privy council, complaining that the earl of Argyle, who, since his rupture

with Morton, had been living in his own country, was collecting a large

force, ostensibly with the view of punishing some disturbers of the public

peace, but really, as he alleged, to attack and harass him, the said

laird, on which proclamation was made, prohibiting the earl from

assembling any of the lieges in arms, and from troubling Glengarry, under

the pain of treason. Various other complaints were made against Argyle for

oppressive and illegal conduct; particularly by John, the son and heir of

James Macdonald of Castle Camus in Skye, and John Maclean, the uncle of

Lauchlan Maclean of Dowart, who were both kept prisoners in Argyle’s

castle of Inchconnell in Lochow, without warrant; and by Lauchlan Maclean,

the young chief of Dowart, whose isle of Loyng was invaded and plundered

by a party of Campbells sent by Argyle. [Gregory’s Highlands and Isles

of Scotland, p. 216.]

On 4th

March 1578, the earls of Argyle and Athole, with other noblemen, assembled

at Stirling, and advised the king to deprive Morton of the regency, and to

take the government into his own hands, which was accordingly done. On

this occasion Argyle was made a member of the new council chosen to direct

the king, who was then only twelve years of age. A few weeks thereafter,

however, Morton again got possession of the king’s person, when Argyle and

Athole took up arms to rescue his majesty, and issued a proclamation

against the late regent. The forces on both sides gathered at Stirling,

the earl of Argyle alone bringing two thousand five hundred Highlanders to

the assistance of those who opposed Morton’s return to power. By the

mediation, chiefly, of Bowes, the English ambassador, an accommodation was

brought about between the hostile factions, and on the 10th

August 1579, Argyle was appointed lord-high-chancellor of the kingdom.

After this he was apparently reconciled to Morton’s administration. On the

28th of January 1581, with the king and many of the nobility,

he subscribed the second Confession of Faith. He was one of the jury on

the trial of Morton, 1st June of that year. At the opening of

the parliament held the following October, he bore the sword, and on the

last day of November, when the king went again in state to the Tolbooth,

he carried the sceptre. He died in October 1584, after a long illness. He

married, first, Janet, eldest daughter of Henry, first Lord Methven,

without issue; secondly, Lady Agnes Keith, eldest daughter of William,

fourth earl Marischal, widow of the regent Moray, by whom he had two sons,

Archibald, seventh earl of Argyle, and the Hon. Sir Colin Campbell of

Lundie, created a baronet in 1627.

Archibald, seventh earl of Argyle, was under age when he succeeded his

father. The dissensions among his guardians, and the assassination of

Campbell of Calder, one of them, have been already related [ante,

ART. BREADALBANE, earl and marquis of.] The conspiracy among the chiefs of

the western Highlands, having for its object the death of the young earl

of Argyle, as well as that of the “bonnie earl of Murray,” is likewise

there alluded to. The principal person interested in his death was his

kinsman Archibald Campbell of Lochnell, one of his guardians, and the next

heir to the earldom; a dark and ambitious spirit, who never relinquished

his designs against the lives of the earl and his brother, that he might