Leith and Edinburgh then

became the chief centres of the linen manufacture in Scotland. There was a

large factory in the Citadel and another in Leith Wynd beyond the Low

Calton, and both had their bleaching greens in the meadows by the

waterside at Bonnington. Owing to her proximity to the great Border sheep

pastures Leith had always had a large trade in the export of wool, and,

placed as she was on the east coast, no Port could have been more

favourably situated for importing the finer foreign wools and all dyes and

other materials necessary for their manufacture into cloth. Both the Leith

and Edinburgh districts, therefore, became leading centres for woollen

manufactories, for James Watt had not yet invented the steam-engine which

led to the great coal and iron fields of the west becoming Scotland’s

chief industrial centres.

But the home-grown wool was

unfit for any save the coarser kinds of cloth, such as blankets and the

hodden grey from which the dress of most Scots was made in olden days.

England, France, and the Netherlands jealously forbade the use of their

fine wools for any but their own manufactures. Supplies had, therefore, to

be imported from Spain and Portugal in return for cargoes of oats, barley,

fish, skins, and coarse cloth. But, despite her favourable situation for

continental trade, a constant and sufficient supply of this finer wool

from the Peninsula was difficult to maintain.

Voyaging in Spanish waters

was peculiarly subject to "sea hazards and pyrats," the pirates

there being the sea-rovers of Algiers and Sallee, at whose very name wives

and mothers of Leith sailormen turned pale. The slow-sailing Leith barques

became an easy prey to those. "savadge and merciles infidels ye

Turkes in Argeirs," as the wife of a Leith mariner of those days

described the sea-wolves of the Mediterranean, by whom Leith seamen were

so often enslaved. Agents in southern Spain did a regular business in

ransoming such unfortunates, and collections in Leith were accustomed to

be taken in an endeavour, not always successful, to effect their release,

as in 1646, to quote one example, for the crew of David Balfour’s ship

"who are lying captive among ye Turks in

Argeir "—the old name for Algiers, as one may see on reading

Shakespeare’s Tempest.

Factories for the

manufacture of woollen cloth of the finest quality were established in

Leith, Leith Wynd, and at Bonnington, which seems to have been quite a

hive of industry in the seventeenth century. The factory at Bonnington was

originally under the superintendence of seven Flemings, who not only

introduced the most up-to-date methods in the production of the finest

woollen cloths, but also engaged to teach them to native workmen. In all

there were more than fifty business establishments that received the

privileges of a manufactory from the State between the Restoration and the

Union of 1707, and of these a very considerable number were located in the

Leith district, owing to the facilities for trade afforded by the Port.

Leith ships of any size,

owing chiefly to the difficulty of obtaining the necessary supply of

timber, were still built in Holland, and their equipment of sails, ropes,

and cordage had to be imported from the same country, as in the days of

James IV. nearly two hundred years before. A beginning was now made in

remedying this state of matters by the establishment of a sailcloth

factory in Yardheads and of a rope-walk in Newhaven, two industries for

which Leith has to-day a world-wide fame. It was now, too, that the

sawmill, to which Mill Lane led for so many long years before Junction

Street was formed, was founded, with the exclusive right of sawing all

timber by machinery, driven, of course, by water power, within a radius of

fifteen miles of it. Farther up the Water of Leith was a factory for

beaver hats which continued for more than a hundred years, and another for

making gunpowder, both of which are commemorated to-day in the names of

the districts — Beaverhall and Powderhall — in which they were

erected.

The funds for the support

of King James’s Hospital in the Kirkgate had been neither honestly nor

wisely administered. Part of the building, in order to help the funds, was

let as a "stiffing house"—that is, as a starch factory—while

another portion was utilized for the manufacture of "prins" and

needles. There was a "sugarie" or sugar-house in the Old

Sugar-house or Candle Close in Tolbooth Wynd, and two soap-works were now

at work in the town. Evidently the good folk of Leith and Edinburgh were

making a beginning at washing every day. The old one in Riddle’s Close,

under the new management of the Balfour family, now of Pilrig, was in a

very flourishing condition, while a new one in the grounds of Coatfield’s

Lodging did much to contribute to setting up the trade with Archangel.

Its proprietor, Robert

Douglas, was a man of much commercial activity and enterprise, and a great

promoter of industries in Leith, where he had also established a pottery.

The last member of this family to be associated with the Port was Miss

Anne Douglas, who died in Trinity in 1910. Then we must not forget the

glass-works, of which there were two at this time, the larger in the

Citadel and the smaller in Yardheads. In the next century they were to

number seven. These were the more important of the industries founded in

Leith during this period of progress. They show that Leithers at this time

were full of that energy and enterprise which has always characterized the

business men of the town, who were then, as now, doing their part in

advancing the material well-being of the country.

But England’s commercial

policy was no less hurtful to Leith’s trade than her policy of

protecting her home industries against competition from foreign countries,

among which Scotland was included. Under Cromwell’s rule Scottish

merchants enjoyed equal trading rights with those of England, both with

foreign countries and the Plantations, as the Colonies were then called.

At the Restoration all this was changed, for England, by her Navigation

Act of 1661, declared that no goods were to be imported into, or exported

from, the Colonies except in ships belonging to England or the

Plantations.

Such a law was quite in

accord with the colonial policy of that time, for Scotland had contributed

nothing, either in blood or treasure, to the acquisition of the

Plantations. But Scotland was anxious to find some market for her linens

and woollens and her newly established manufactures. As she was now shut

out from English markets, and to a large extent from those of the

Continent, both by trade policy and William’s French wars, she could

only find a market for her goods in the Colonies, where there were no

established manufactures. Scotland, however, had no colonies of her own,

and she was now shut out from trading with those of England by the

Navigation Act.

But Leith’s "sugarie"

in the Old Sugar-house Close could not carry on without supplies of raw

sugar, nor could the hat factory at Beaverhall continue to gratify the

demand for beaver hats without a supply of beaver skins for their

manufacture. Fortunate was it for Leith, therefore, that the trade

regulations of those days were more strict in theory than in practice. For

this reason, in spite of the Navigation Act, she was enabled to carry on a

considerable trade with the Plantations in woollens, linens, stockings and

other "Scotch goods," as they were then called. This trade was

greatly encouraged by the colonists, because the Scottish goods, though

coarser in quality, were cheaper in price than those sent from England.

Another of Leith’s

exports during this period was "notorious vagabonds," with whom

she was kept well supplied from Edinburgh. Strange as it may seem these

"vagabonds" were much prized by the colonists, for despite their

designation they made excellent and trustworthy servants. Some of them

had, no doubt, been notorious enough, but many were no worse than poor

Covenanters and "absenters from the kirk," who, like the two

hundred or more prisoners from Greyfriars’ Churchyard wrecked in the

ill-fated Crown, had refused to conform to Episcopacy.

This

trade in shipping off prisoners as slaves to the Plantations was a paying

business, and English vessels voyaging to America and the West Indies

would often come to anchor in Leith Roads and ship as many prisoners as

could be had, for the Privy Council was always ready to empty the prisons

and "be rid of such vermin." These vessels would then go

North-about and continue their voyage to the west. Indeed, so profitable

did merchants and skippers find the trade, that people were often

kidnapped, a practice made familiar to us by Stevenson’s exciting story

of the adventures of David Balfour, and by the true story of the life of

Peter Williamson, the man who issued the first Edinburgh Directory in

1773. As late as 1810 a butcher of North Leith named Leadbitter was

imprisoned for kidnapping boys to serve aboard ships voyaging to distant

lands.

This

trade in shipping off prisoners as slaves to the Plantations was a paying

business, and English vessels voyaging to America and the West Indies

would often come to anchor in Leith Roads and ship as many prisoners as

could be had, for the Privy Council was always ready to empty the prisons

and "be rid of such vermin." These vessels would then go

North-about and continue their voyage to the west. Indeed, so profitable

did merchants and skippers find the trade, that people were often

kidnapped, a practice made familiar to us by Stevenson’s exciting story

of the adventures of David Balfour, and by the true story of the life of

Peter Williamson, the man who issued the first Edinburgh Directory in

1773. As late as 1810 a butcher of North Leith named Leadbitter was

imprisoned for kidnapping boys to serve aboard ships voyaging to distant

lands.

And so when ships like the Hopewell

of Leith sailed with a cargo of "Scotch goods" to the

Plantations, to return with tobacco and supplies for the sugarie and the

factory at Beaverhall, James Graham and Thomas Hamilton, merchants in

Edinburgh, her owners, would "crave the delivery of such idle

vagabonds and other persons as may be ready to go to the

Plantations." These unfortunates were generally kindly treated by the

planters and were usually set free after a number of years, when they

settled down on small plantations of their own. Along with those Scots who

now emigrated to the Colonies instead of serving in foreign armies or

wandering as pedlars and traders in Poland, they naturally kept in touch

with their own countrymen, and encouraged them to come and trade with

them. And in this way Leith vessels continued to sail to the Plantations

in spite of every English regulation to keep them out.

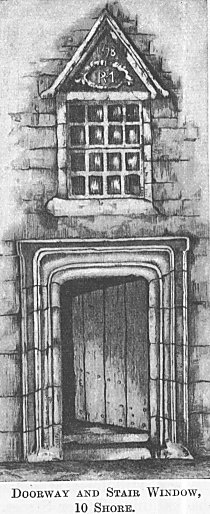

The larger ships required

to meet the needs of those more distant voyages brought about the first of

the many harbour extensions that have been made to accommodate Leith’s

ever-growing trade. The Shore had been gradually stretching seawards

beyond the King’s Wark, and in 1677 Robert Mylne, the King’s Master

Mason, obtained a grant of the waste land at the mouth of the harbour on

which he erected "for his own use and benefit the great stone

tenement upon the Shore of Leith," to quote a family charter. This

tenement, now numbered 10 Shore, is still owned by the Mylne family. It

possesses a beautifully moulded doorway and stair window, in the pediment

of which, within a chaplet of roses, are the initials of its famous

builder, R. M., and the date 1678. Here resided Robert Mylne’s son

William, who was the first of the family to drop the old title of Master

Mason for the new one of Architect. He was one of the

supporters of the king’s policy of establishing Episcopacy in South

Leith Church during the "killing time," as one would expect the

son of the King’s Master Mason to be.

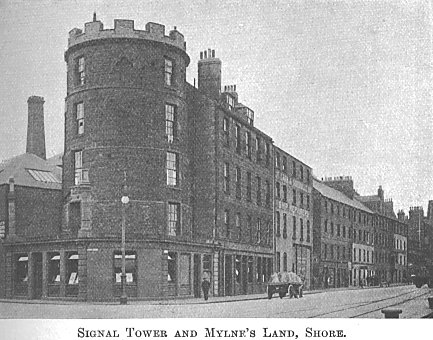

In

1685 Robert Mylne received another grant of land along the seashore, where

he undertook to erect a seawall to resist the encroachment of the waves,

and to construct a windmill, leaving between it and the north gable of his

tenement a suitable entrance to the adjoining Timber Bush. The great stone

tenement, the windmill, and the entrance to the Timber Bush may still be

seen on the Shore. The windmill is now the Old Signal Tower used to-day by

Messrs. Cran as a part of their works. A portion of the seawall, which

Robert Mylne built in 1685 to protect the stores of wood within the Timber

Bush from being washed away by the sea, still forms the lower part of the

walls of the shacks lining Tower Street, and in them one can easily

discern the built-up openings, like embrasures for cannon, through which

the timber cargoes floated from the ships were hauled for storage within

the Timber Bush.

In

1685 Robert Mylne received another grant of land along the seashore, where

he undertook to erect a seawall to resist the encroachment of the waves,

and to construct a windmill, leaving between it and the north gable of his

tenement a suitable entrance to the adjoining Timber Bush. The great stone

tenement, the windmill, and the entrance to the Timber Bush may still be

seen on the Shore. The windmill is now the Old Signal Tower used to-day by

Messrs. Cran as a part of their works. A portion of the seawall, which

Robert Mylne built in 1685 to protect the stores of wood within the Timber

Bush from being washed away by the sea, still forms the lower part of the

walls of the shacks lining Tower Street, and in them one can easily

discern the built-up openings, like embrasures for cannon, through which

the timber cargoes floated from the ships were hauled for storage within

the Timber Bush.

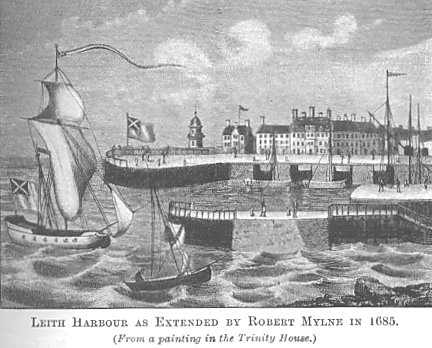

This windmill built by

Robert Mylne at the entrance to the harbour, together with the one at St.

Anthony’s, and a third built on the

town ramparts near Links Lane behind South Leith Church, must have given a

quaint Dutch-like aspect to Leith in those brave days of old in

approaching it from the sea. It was from this harbour as reconstructed by

Robert Mylne that the Darien Company’s expedition sailed away in such

high hope in 1698, and it is substantially this harbour we see depicted in

the old Dutch picture now in the Trinity House.

Scotland, in adopting a

policy of protecting her new industries against competing products from

England and continental countries, went far to shut her own commodities

out of European markets. Leith’s illicit trade with the Plantations did

not compensate her for the loss of her trade with England, France, and the

Netherlands. During King William’s wars with France her commercial

intercourse with the Baltic had increased as that route was safer from the

attacks of French war ships and privateers than those to Holland and Spain

and Portugal.

But Scotland, and more

especially the Leith and Edinburgh part of it, had become a manufacturing

centre, and markets for the disposal of her manufactured goods were

urgently needed. Having spent what capital she could gather together in

establishing manufactures, she now gave what money she had left to found

the Darien Company to settle a colony in Darien, which was to be a great

colonial market for the disposal of Scottish manufactures. The maximum

amount of stock one could hold in the Darien Company was £3,000, the sum

subscribed by the Corporation of Edinburgh, but none of the sixteen Leith

shareholders on the list approached this amount. The highest was the share

of James Balfour, the ancestor of the Pilrig family and a partner in the

soap-works in Riddle’s Close and the powder-mills at Powderhall, who

subscribed £2,000, while Robert Douglas, his rival in the soap trade,

with more Scots caution, put his name down for the modest sum of £100.

The Trinity House "adventured" £200, as also did Mr. William

Wishart, the minister of South Leith.

And

so on a fine day in July 1698 the whole population of Edinburgh and Leith,

we are told, poured down upon the pier and sands of Leith to see the five

ships, which had been specially built at Amsterdam and Hamburg for the

expedition, weigh anchor in Leith Roads, and to cheer loud and long as the

vessels hoisted sail and made their way down the Firth. With the second

expedition, which sailed in the following year, went as chaplain the Rev.

Archibald Stobo, from whose daughter, Jean, was descended Martha Bulloch,

the mother of the late President Roosevelt.

And

so on a fine day in July 1698 the whole population of Edinburgh and Leith,

we are told, poured down upon the pier and sands of Leith to see the five

ships, which had been specially built at Amsterdam and Hamburg for the

expedition, weigh anchor in Leith Roads, and to cheer loud and long as the

vessels hoisted sail and made their way down the Firth. With the second

expedition, which sailed in the following year, went as chaplain the Rev.

Archibald Stobo, from whose daughter, Jean, was descended Martha Bulloch,

the mother of the late President Roosevelt.

The expeditions, instead of

founding a colonial market as an outlet for Scottish manufactured goods,

ended in disaster, and brought much sorrow to Leith, for of the nine ships

that sailed away only one returned.

The feeling of hatred

against King William and the English, and especially against the East

India Company, who largely contributed to the failure, and deliberately

left the colonists to whatever fate might befall them, was deep and

bitter. It soon showed itself in unfriendly and hostile acts that still

further inflamed the feeling of enmity between the two countries. After

the failure of their great colonial scheme the Darien Company still

carried on a shipping trade with the East. This was strongly resented by

the East India Company, who looked upon the countries round the Indian

Ocean as their peculiar sphere for trading. They seized and sold the Annandale,

one of the Darien Company’s ships, while another, the Speedy

Return, had sailed to the East three years before, and, in spite of

her name, had not since been heard of.

Just at this time an East

Indiaman, the Worcester, driven by stress of weather, sought

shelter in the Forth. The Worcester did not belong to the East

India Company, as was supposed at the time, but to a rival company founded

in the same year as the Darien Company. Rumours began to get abroad that

Captain Green and the crew of the Worcester had captured a Scottish

ship off the Malabar coast, and had murdered the crew. It was at once

concluded that this ship was the Speedy Return, and that an

overruling Providence had directed Captain Green and his men to the Forth

for punishment. The upshot was that Captain Green and two of his crew were

tried, and, without a shadow of proof, condemned to be hung as pirates on

Leith sands, where the angry population of the two towns crowded to see

that they did not escape. If the crew of the Worcester had seized

any Scottish ship it was not the Speedy Return, for that much

misnamed vessel, it would seem, eventually found her way back to Leith.

The feeling of enmity deeds

such as these stirred up between the two countries was now so strong that

any further acts of hostility could only end in war. It was seen that the

two countries must either once more become separate kingdoms or be brought

into closer union, and have the same rights and privileges. They were

wisely guided, and the result was the Act of Union of 1707. The good folk

of Edinburgh and Leith were opposed to the Union, and on 1st May, the day

on which the Act came into force, the musical bells of St. Giles’, which

no longer hang in the steeple, gave sympathetic expression to the feelings

of the people by pealing forth the melancholy old Scots tune, "O why

should I be sad upon my wedding day?"