The execution of Charles I.

filled the Scots with grief and anger, for they were loyal as well as

religious. They now proclaimed his son Charles II. king, and a commission

which sailed from Leith invited him over from Holland, where he lived as a

fugitive from his kingdom. Unwilling to accept the crown by subscribing to

the Covenant, he first sent over the Marquis of Montrose to effect a

rising in his favour. But Montrose was defeated and captured, and brought

over the Forth to Leith, where a public thanksgiving in gratitude for his

overthrow had been held in St. Mary’s Church two days before. On

Saturday afternoon the 18th of May he was taken to Edinburgh, when

bonfires blazed and the church bells rang out a merry peal to mark the

event. Charles now agreed to the Covenant, and three weeks later landed in

Scotland and rode to Stirling Castle.

The reception and

acknowledgment by the Scots of Charles as their lawful king at once

provoked the English Parliament to war, and Cromwell was sent to invade

Scotland and reduce the country to obedience to the Commonwealth. Cromwell’s

army, in accordance with the strategy of former English invasions, was

accompanied by a fleet, which kept in touch with the troops as they

marched along the coast, and came to anchor in Leith Roads without

opposition. For at this time Scotland had only one ship of war, the good

ship James of Leith, which had somehow been pressed into service

for Montrose’s expedition, and, after his execution, had been recaptured

and brought into Leith, with all his secret papers aboard. Leith’s

shipping had never been so reduced, for with no ships of war to protect it

it had become a prey to the attacks of royalist privateers and the many

pirates with which the North Sea swarmed at this time. And now Cromwell’s

fleet under Admiral Deane and Captain Penn, the father of the founder of

Pennsylvania, captured what remained, and, destroying some, pressed the

rest into the English service.

The fortifications of Leith

were repaired and strengthened under the superintendence of John Mylne,

the King’s Master Mason, and a Covenanting army under Sir David Leslie,

who could outmatch even Cromwell himself in the art of war, mustered on

the Links. The Scots defences were mainly directed to protecting Edinburgh

and Leith, for Leslie was determined that there should be no such

occupation of Leith by the enemy as in the days of Hertford’s invasions,

or that of the French in the days of Mary of Guise. Cromwell could have

entrenched his whole army around its walls, and, with his navy to ensure

constant supplies by sea, could have made it a base from which to bridle

the whole of Scotland.

Leslie’s plans to defeat

any such purpose were wisely and skilfully chosen. To make it impossible

for the enemy to enter Leith by sea a great boom was drawn across the

mouth of the harbour. The landward defences were even stronger. The deep

rugged valley of the Water of Leith formed an impregnable natural defence

in the rear, while, facing the east, to resist the enemy’s approach,

Leslie had a great ditch or trench dug from Holyrood to St. Anthony’s

Port, opening into the Kirkgate a little above Laurie Street. Parallel to,

and behind this defensive ditch, on the line of the present Leith Walk,

was a broad rampart of earth which no artillery fire could breach, and

which was protected by many batteries of "Dear Sandy’s Stoups"—the

cannon of Sir Alexander Hamilton, who was now sleeping his last long sleep

in the family vault in Duddingston Churchyard. His cannon were so named

from their resemblance to the long hooped wooden pails or stoups then, and

for two centuries afterwards, used for carrying water from the public

wells.

Leslie’s defences proved

insurmountable to the English, and baffled every attempt of Cromwell and

his Ironsides to break through them. Knowing his troops to be no match for

Cromwell’s veterans in the field, Leslie resolved not to be lured from

his trenches into the open. In front of his huge rampart lay the

unenclosed fields, and beyond were the Figgate Whins, a great waste of

heather and marsh, and much overgrown with clumps of whims, like the

Whinny Hill on Arthur’s Seat. The inhabitants of Restalrig and other

villages had sought refuge within the city walls or behind Leslie’s

ramparts, for the terror of Cromwell’s name had everywhere preceded him

from Ireland, from whose conquest he had just returned to enter on his

Scottish campaign.

On Sunday evening, July 29,

1650, Cromwell reached Musselburgh, where he encamped his infantry on the

Links and his cavalry in the town. Here he had his headquarters for the

next month, and, on an elevation on the Links in front of Linkfield House,

the site of Cromwell’s own tent may even yet be traced in the grass.

Next morning he led his whole force forward to the Figgate Whins around

Craigentinny, posting his cavalry beside Restalrig, his foot in "that

place callit Jokis Ludge," and his guns at the foot of "Salisberrie

Hill, within the park dyke." There was hot skirmishing around Lochend

and the Quarry Holes, whose mounds may still be seen within the east end

of London Road Gardens. The Scots were driven in within their trenches by

that dare-devil Puritan commander, General Lambert; but the fighting here

was perhaps a feint to screen the main object of his attack, which was to

bombard and capture St. Leonard’s Hill, from which, with his artillery,

Cromwell could have dominated the city. His men were utterly routed and

driven off. At the same time four ships of the English fleet bombarded

Leith with fire-balls and other missiles; but we have no record as to how

their onslaught was repelled. On the whole the honours of the day remained

with Leslie and the Scots, and the baffled English fell back upon their

camp at Musselburgh.

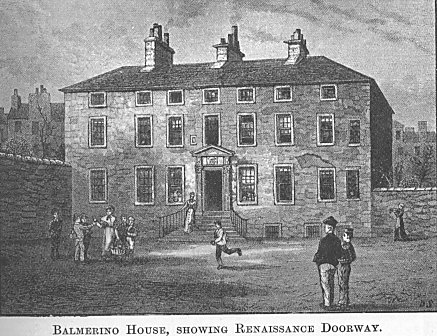

That

same day King Charles had ridden from Stirling to Leith, and had watched

the day’s fighting from the Castle Hill. In the evening he passed along

the line of trenches to Leith, when he received a most joyous and

boisterous welcome from the troops, and took up his residence in the once

noble mansion of Lord Balmerino, which still stands just off the Kirkgate,

though now shorn of all its former state. There is also a tradition that

the young king was entertained by the "bold Buccleuch" in the

great mansion in Quality Street, which was then an inn, and is to-day a

good specimen of old Scottish street architecture. The young king ardently

wished to join in one of the sorties against the enemy; but Leslie would

on no account agree to this, as the risks were too great. After a stay of

several days at Balmerino House, the Scots leaders, to his own great

disappointment, insisted on King Charles seeking a safer residence at

Dunfermljne.

That

same day King Charles had ridden from Stirling to Leith, and had watched

the day’s fighting from the Castle Hill. In the evening he passed along

the line of trenches to Leith, when he received a most joyous and

boisterous welcome from the troops, and took up his residence in the once

noble mansion of Lord Balmerino, which still stands just off the Kirkgate,

though now shorn of all its former state. There is also a tradition that

the young king was entertained by the "bold Buccleuch" in the

great mansion in Quality Street, which was then an inn, and is to-day a

good specimen of old Scottish street architecture. The young king ardently

wished to join in one of the sorties against the enemy; but Leslie would

on no account agree to this, as the risks were too great. After a stay of

several days at Balmerino House, the Scots leaders, to his own great

disappointment, insisted on King Charles seeking a safer residence at

Dunfermljne.

During Charles’s stay in

the Kirkgate, a hospitality for which his host was ill-requited after the

Restoration, the Scots determined to surprise the English by beating up

their quarters at Musselburgh under cover of night. The success of such a

dangerous enterprise, of course, mainly depended upon their making their

attack from the most unexpected quarter. About midnight over one thousand

horsemen rode out from Leith towards Restalrig. Making a wide detour, they

forded the Esk far above the most advanced line of English outposts, and

rode along the high ground to the east end of Edgebucklin Brae. Here they

formed up for the charge, and, dashing down upon the Links, broke right

through the English camp, upsetting tents and cutting down all who

attempted to oppose their progress. But Cromwell’s cavalry quartered in

the town soon rallied to the fray, and the Scottish horsemen had to make a

straight run for Leith with the English cavalry close on their heels.

And so for a month the

fight went on. Cromwell was not only unable to break through the Scots

entrenchments, but every attempt to pass towards Queensferry to cut off

Leslie’s supplies from the west, and so starve him into surrender, was

foiled. Baffled and defeated, his men dying daily of disease, thanks to

the Lammas floods, which seemed to be in alliance with the Scots, Cromwell

could do nothing but retreat.

And then there followed the

disastrous Scottish defeat on the field of red Dunbar because of their

disobedience to those very tactics of sitting tight which had completely

baffled the English at Leith. Cromwell at once returned to Edinburgh and

occupied Leith, when "the ministers and most part of all ye honest

people fled out of the town for fear of ye enemie." The charter chest

of South Leith Church, containing the communion plate, the records, and

other documents, was buried beneath the floor of the church, where it lay

for nearly two years before it was thought safe to remove it.

Ere long most of those who

had fled the town returned, for Cromwell, by wise and just government,

always endeavoured to win the Scots to the side of the Commonwealth. But

the hearts of the Leithers were with King Charles, unworthy as he was to

prove himself of their loyalty and devotion; and however wise and just

their rule, the English well knew that the Leithers were ready to flame

into rebellion when the opportunity arose. It was for this reason that

General Monk shut up the two parish churches, and no prayers of the

Leithers could induce him to reopen them, for he looked on the Scottish

clergy as "trumpets of sedition," as they all preached in favour

of the monarchy. Let us give the English commander’s reason in his own

words, for they show the Leithers still, as Henry VIII.’s ambassador

found them in days before the Reformation, "noted all to be

Christians."

"There was," Monk

tells us, "so greate a resort of Scotchmen that there would bee above

a thousand of them there on the Lord’s Day, which I thought not safe to

suffer any longer, the Magazine wherein our arms and ammunition are being

so near the Church."

This magazine consisted of

four closely adjoining buildings, King James’s Hospital, the vault

beneath the old Trinity House from which they evicted the Grammar School

to one of the lofts of Riddle’s soap-work, the Windmill Yard of the

ancient St. Anthony’s Hospital, and the churchyard. On the expulsion of

the congregation the church itself was used for housing their artillery.

Monk, like a wary and prudent commander, thought the English garrison ran

great risks with so large a weekly gathering in the immediate

neighbourhood of what were their military depots until a citadel was built

where both troops and stores could be safely lodged.

The

people of Leith were allowed to hold church services where they pleased,

so long as they did not gather in the town. And so for nearly seven years

the congregation had to wander in the wilderness, worshipping for the

greater part of this period at Restalrig, but sometimes holding their

services around the Giant’s Brae, when, through the influence of James

Riddle with the deputy-governor of the town, St. Anthony’s Port was kept

open "upon the Lord’s Day betwixt 7 hours in the forenoon until 2

hours in ye efternoon for outgoing and incoming of the people to sermone

in the Links."

The

people of Leith were allowed to hold church services where they pleased,

so long as they did not gather in the town. And so for nearly seven years

the congregation had to wander in the wilderness, worshipping for the

greater part of this period at Restalrig, but sometimes holding their

services around the Giant’s Brae, when, through the influence of James

Riddle with the deputy-governor of the town, St. Anthony’s Port was kept

open "upon the Lord’s Day betwixt 7 hours in the forenoon until 2

hours in ye efternoon for outgoing and incoming of the people to sermone

in the Links."

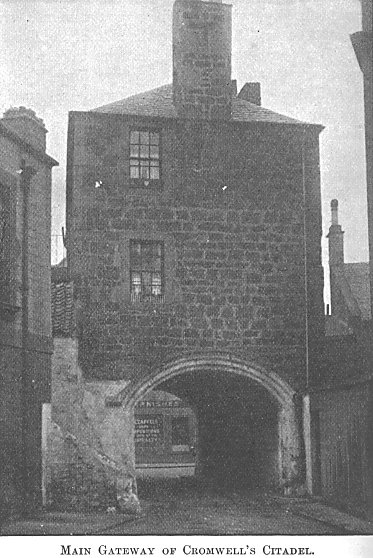

The Citadel, "passing

fair and sumptuous," built by Monk, was erected on the site of the

Chapel of St. Nicholas at the foot of Dock Street, where its great arched

gateway may still be seen. The house over the archway, according to

tradition, was the meeting-place of the officers and men of Cromwell’s

Ironsides in Leith who held Baptist views. We know that there were

Baptists in Leith during the Cromwellian period who were wont to go to

Bonnington to be "dippit in the clear rynnand water." The house

over the Citadel archway, however, is of later date than Cromwell’s

time, as is shown by the stair by which it is reached being outside,

instead of inside, the Citadel gateway.

When the Citadel was built

South Leith Church was restored to the parishioners. The opening services

were marked by much rejoicing. The church had been given up largely

through the influence of James Riddle, the wealthiest and most

enterprising merchant in the town, and one in great favour with Monk and

the other English commanders He had succeeded Uddart and Maule in the

monopoly of the soap manufacture in Leith. Riddle’s Soap-work was at the

corner of the Dub Raw and Riddle’s Close. This close, to which he was

name-father, Leithers, with no knowledge of James Riddle and the town’s

indebtedness to him, have in recent years misnamed Market Street.

As there is already a Market Street in Greater Edinburgh with much more

claim to the title, let us hope that Leith, in commemoration of the public

service of its old-time patriotic citizen, James Riddle, will go back to

the ancient designation, and, as the old thoroughfare is no longer a close,

will rename it Riddle Street.

It may be that the two old

skew stones bearing the initials I.R. or J.R. and the date 1659, built

into the gables of the small tenement in St. Andrew Street looking towards

Riddle’s Close (Market Street), are a relic of James Riddle’s

soap-work which used to stand immediately across the street from this

building.

But we have not yet

exhausted the interest associated with the name of James Riddle. His

father had been one of those enterprising Scots whom we have already seen

embarking at the Shore of Leith to push their fortune in Poland. Having

acquired great wealth there, he returned to Edinburgh, and set up house in

that aristocratic quarter of the Old Town, the Lawn-market, where Riddle’s

Close, one of the finest in the Royal Mile, still preserves his name, and

where his house yet remains. His eldest son James, as we have seen, became

one of Leith’s leading townsmen, and an influential member of St. Mary’s

Kirk Session. From the address on one of his letters we know that Cromwell

spent one night in Leith, when, according to a doubtful tradition, he was

the guest of James Riddle. He is much more likely to have been lodged in

Balmerino House, in whose extensive garden some of his chief officers were

quartered in tents. In grateful remembrance of his many services, the Kirk

Session bestowed on Riddle and his heirs a large space in the nave of the

church for a family pew for all time coming. Such, in brief, is the story

of James Riddle, one of Leith’s early benefactors and a man who nobly

deserves the simple recognition of having his name restored to the street

in which, by his spirit and enterprise, he did so much to build up the

trade, not only of Leith, but even of Scotland itself.

Of Leslie and his great

rampart we ought to be reminded every time we go up and down Leith Walk,

for there we are walking along the huge mound of defence behind which he

baffled the mighty Cromwell in 1650. It has now taken the place of the

Easter, the Bonnington, and the Restalrig Roads as the main highway to the

city, because, since the opening of the North Bridge in 1770, Leith Walk

has been the most direct route. Before 1650 what is now Leith Walk was

merely a straggling pathway known as Leith Loan, that wound its way over

the heathery waste and through the meadows and cornfields that then lay

between the city and its port. Leslie’s rampart became a gravelled

roadway twenty feet wide, for pedestrians only, which Edinburgh citizens

used as their "walk" on their way to enjoy the sea breezes on

the pier of Leith, that in those days was merely a continuation of the

Shore beyond the Old Signal Tower.

By

degrees another footpath was formed at the bottom of the mound, and the

two became known respectively as the High Walk and the Low Walk, the one

being eighteen feet higher than the other. The level of the Low Walk is to

be seen at Springfield Cottage above the Alhambra, and also just north of

Haddington Place, where the house below the level of the street, once the

residence of the Curator of the Botanic Gardens before they were removed

to Inverleith, still shows parts of the old boundary wall that ran along

the Low Walk. For years Leith Walk was a dreary, unsafe way, with no broad

pavements lined with street lamps, and thronged with foot passengers. Not

only was there much risk of falling off the high footpath on to the one

below on dark nights, but the long roadway was also beset with foot-pads.

By

degrees another footpath was formed at the bottom of the mound, and the

two became known respectively as the High Walk and the Low Walk, the one

being eighteen feet higher than the other. The level of the Low Walk is to

be seen at Springfield Cottage above the Alhambra, and also just north of

Haddington Place, where the house below the level of the street, once the

residence of the Curator of the Botanic Gardens before they were removed

to Inverleith, still shows parts of the old boundary wall that ran along

the Low Walk. For years Leith Walk was a dreary, unsafe way, with no broad

pavements lined with street lamps, and thronged with foot passengers. Not

only was there much risk of falling off the high footpath on to the one

below on dark nights, but the long roadway was also beset with foot-pads.