|

FORT-WILLIAM AND THE

GORDON LANDS.

To all descended of

the house of Mackintosh, the parish of Kilmallie will, as the

birthplace of Eva, the honoured mother of Clan Chattan, ever be

interesting. Fifty-one years ago, 1844, I paid it my first visits,

two expeditions remaining indelibly fixed in my memory. One of these

was a drive to Glenfinnan to see the monument to Prince Charles, and

the other, crossing Lochiel and Loch Linnhe, accompanied by a

friend, to see Inverlochy Castle and Fort-William, and on our return

nearly drowned in a sudden storm, whence we had to run for several

hours into the shelter of Camusnagaul. The day's misfortunes did not

end, there, for being dark by the time we left the bay, we went

aground on a bank, since, I think, removed, not far from Corpach

Heads, where we had to remain in the cold and darkness for some

time, until the tide had sufficiently advanced to float us off. All

this was in the month of January. My recollections of Fort- William

were therefore of a mixed character, in consequence of the after

proceedings, but I well recollect its streets as being very dirty

and the extraordinary number of public-houses it contained.

Fort-William is now the growing place of the West Highlands, and is

entering on what I trust and am almost certain will be a long reign

of prosperity—a West Highland emporium—having, or to have by and

bye, outlets in every direction of the compass.

I wish it, as I have

already publicly wished it, every prosperity, and desire that its

appearance from the sea may in time be much improved by a carriage

marine parade, while the water power available quite at hand should

be utilised for electric purposes, and thereby the gas-works and

other objectionable smoky erections done away with. The houses if

white-washed, rising tier by tier from the sea, would look grand.

It would be idle as well as unprofitable

to speculate on the condition of the people in prehistoric times, or

even when in possession of the Comyns. The latter left little

record and did not perpetuate their name. How different from the Macdonalds? Their possession was not much over 150 years—four

generations exactly—yet how the actions of the Lords of the Isles

pervade the whole district—and as for the people, then and now, and

now as then, the surname of Macdonald dominates and predominates.

The old castle of Inverlochy, of which

there are some remains, was no doubt erected in the time of the

Comyns, and it is a great pity that such alien names as Fort-

Augustus and Fort-William have come in place of the dignified and

euphonious Gaelic Killiwhimen, and Innerlochie. When about 1500 the

Earl of Huntly got the lordship of Lochaber, he was bound to

maintain the Castle of Inverlochy for the King's service, but just

as occurred in the case of the Castle of Inverness, the obligation

was, on the Earl's supplication shortly after, either modified or

practically departed from.

Cromwell fortified and extended the

defences of Inverlochy, keeping there a considerable garrison, who,

judging from documents preserved, amused themselves, when left alone

by Lochiel and others, in framing addresses of that snivelling cant

so congenial and natural to the crop-eared Saxon Roundhead. After

the restoration the place fell into decay, but after the Revolution,

Government saw the prudence of having proper fortifications in this

locality ; and early in William and Mary's reign the fort of

Fort-William was erected nearer the sea than Inverlochy, and was

maintained until well on in the present century. A village sprung up

around the Fort, in honour of the Queen called Maryburgh. No regular

title seems to have been granted by the Duke of Gordon, but a money

payment of £70 a year was made by the Board of Ordnance, for at

least 30 years prior to 1787, for the site of the Fort and certain

grounds adjoining, occupied for the accommodation of the garrison.

The village was a Burgh of Barony, with right to hold a weekly fair.

Matters so remained until 1787, when the Duke, desiring to have

things put on a permanent footing, entered into a submission with

the Board of Ordnance, to Mr David Young of Perth, and Mr Angus

Macdonald of Achtriachatan, as valuators. The grounds desired by the

Board were found to extend to 53 Scots acres, whereof it may be

mentioned 4 acres, 2 roods, 20 poles, represented the Fort; 1 acre,

2 roods, 12 poles, the esplanade; 2 acres, 2 roods, the burial

ground; 15 acres, the Point of Claggan in Kilmonivaig, the remainder

being accommodation land. The arbiters fixed the annual value at

£70, instead of £81 claimed, but declined giving an opinion on the

forty years' purchase asked by the

Duke, £4240. Ultimately his Grace accepted £2100, and the necessary

writ was granted, referring to a plan prepared by Major Andrew

Fraser, chief engineer for North Britain, and reserving to the Duke

the salmon fisheries of the rivers and the coast adjoining, rights

of anchorage for accommodating the trade and intercourse of the

village, as also to the inhabitants and villagers, the use and

privilege of the burial ground.

Major Fraser's plan, which was signed in

duplicate, went amissing, and in 1820 the Board of Ordnance wished

the grounds inspected, measured, and substantial march stones put

up. This the Duke agreed to, but the local representatives differed

greatly, while the principals also were not at one. The Duke

maintained that the fort and esplanade were included in the 53

acres, while the Board held that they were not, the matter ending in

the latter acquiescing in the Duke's views.

That "Queen Anne was dead" became

proverbial, and as it was also certain that her sister Queen Mary

was also dead for many years, the Gordons thought the keeping up the

name of Maryburgh inconsistent with their dignity and so altered it

to Gordonsburgh. Not to be outdone, Sir Duncan Cameron, who

succeeded the Gordons in the Burgh of Barony of Inverlochy, called

the village Duncansburgh. It would be difficult, perhaps, to decide

which of the two names was the ugliest; nor is that of Fort-William,

which has supplanted both, a whit less objectionable.

The old rights in the town were merely

entries in the Superior's rent rolls, as so much in name of "feu,"

while others were by way of "rent," and considerable trouble arose

after Sir Duncan Cameron's purchase of Inverlochy in adjusting

matters. These have, it is understood, been settled in course of

time, while the new feus of Lochiel and Glenevis, are outwith the

old settlements in Achintorebeg.

There are now only two proprietors in

Kilmallie east of Loch Linnhe, Lochiel and Mrs Cameron Campbell. The

former has a magnificent sea frontage from Fort-William to

Ballachulish, but it must have been a very severe wrench for him to

part with his portion of Ben-a-bhric and its shielings on the upper

waters of Loch Leven, even though they never adjoined to or included

Lochan-a-Chlaidhe, or the "Fuaran Ard," or the "Cailleach Mhor,"

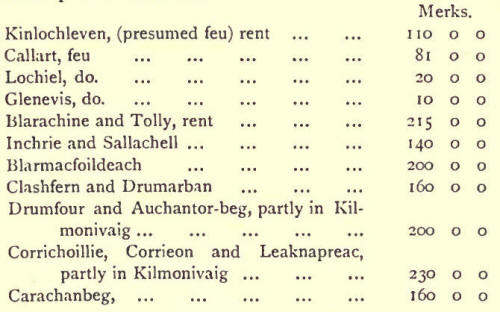

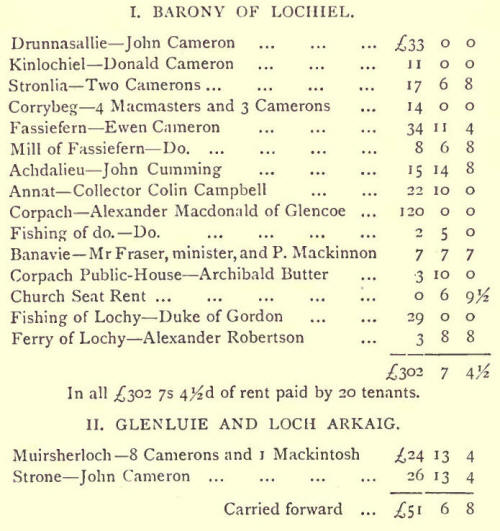

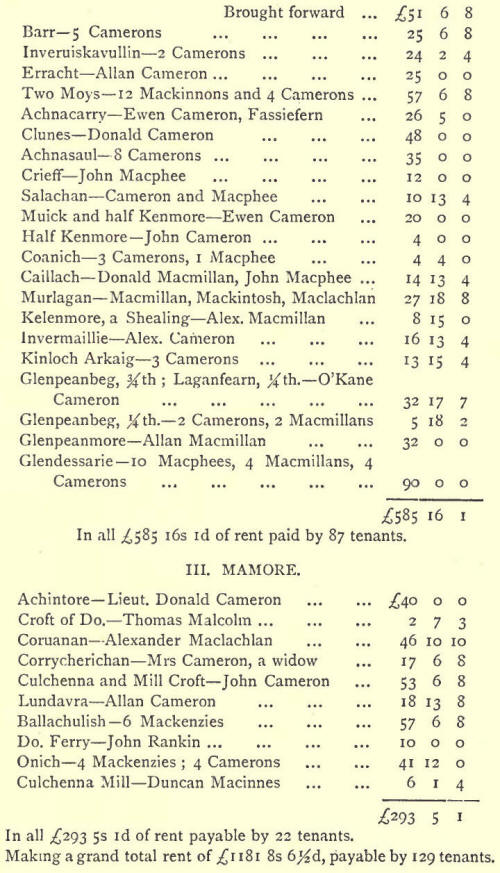

Having already given the Gordon rental of Kilmonivaig, that for

Kilmallie in 1677 is now given. I regret I cannot give the rentals

of the other old heritors—those of Glenevis, Callart, Kinlochleven,

and Lochiel's part of Mamore—

One good point is cheerfully put to the

somewhat meagre credit side of the Gordons in Lochaber during their

three hundred and fifty years' possession, viz, that in 1800 the

farm of Drumarban, within two miles of Fort-William, having fallen

into the Duke's hands, it was broken up and let into crofts, chiefly

for old soldiers of his own fencibles.

So long as there were soldiers at

Fort-William and a staff kept up, there was a good deal of stir in

the place. The markets were generally well attended. The resident

gentry, it might be said, whereof Fort-William was the centre, were,

though scattered, fairly numerous, while many of the larger farms

were occupied by officers on half pay or retired. Gradually, after

the close of the Peninsular War, the strength of the garrison was

reduced, the local resident gentry decayed, the old officers died

out, and stagnation prevailed. Yet at its best, Fort-William society

was not altogether harmonious. Militarism with its parasite train,

is ever exclusive, and the West Highland world whereof Fort-William

was the centre was a century ago rent in twain by a bitter yet most

ridiculous warfare over the Fort- William dancing master, one

Kennedy, who had set up in the place a dancing school in 1802, which

was attended by those who considered themselves the elite.

Of old Highlanders did not need to be

taught, their steps being adapted to the music and its time, and

thus perfectly in harmony. Times were changing, however, and so this

school was opened in Fort-William. Fired with an emulation rather

unsuited to his years and situation in life, Mr J. Macmillan, of the

somewhat mature age of 22 for beginning this kind of schoolery,

whose daily occupation was while by no means dishonourable yet of an

humble nature, viz., that of strapper, presented himself for

admission, which the poor dancing master, glad of support, did not

hesitate to give him. The rest of the scholars, young ladies and

others, with their parents and friends were furious, and insisted

that if the objectionable person whose activity when on the floor

was rather dangerous to others' limbs were not excluded, they would

all leave. This put the poor dancing-master in much distress, and he

offered to instruct Macmillan alone for nothing. Backed up by some

"friends of man," and "universal brothers," not unknown even in the

present day, Macmillan declined, and was in consequence dismissed.

He thereupon raised an action of declarator against the dancing

master, maintaining that so long as he kept open school he was bound

to receive the petitioner in common form with others on payment of

the usual fees, and that if he declined he should be found liable in

heavy damages. This ridiculous case, alter going through the Sheriff

Court, was debated at great length in the Court of Session, talented

advocates gravely debating the pros and cons as if important issues

depended upon it. Local feeling was much embittered, and large sums

were foolishly subscribed to carry on the proceedings.

Alexander Macdonald, son of Charles

Macdonald in the Clachan of Aberfoyle, practised for some years in

Fort- William as a doctor, and afterwards in Knoydart, but he must

not be confused with the well-known surgeon in Knoydart, Alexander

Macdonald, alias Maceachin, called the "Doctor Roy." The first-named

Alexander Macdonald served his apprenticeship with Dr Robert Graham

of Stirling, and his articles were discharged on the 9th of

November, 1761. Like many budding surgeons, Alexander was glad to

accept an appointment on a Greenland whaling ship, starting on his

first voyage early in 1762, as seen by the following certificates:_

"I, Thomas Gairdrier, merchant in

Edinburgh, one of the owners of the ships employed from this port on

the Greenland, and as an acting manager for the other partners, do

certify that the bearer, Alexander Macdonald, surgeon, was by my

appointment examined by a physician of skill, and recommended to be

employed as a surgeon in our ship "The Campbelltown," on the voyage

to Greenland this season, and the commander and crew have reported

to me their entire satisfaction with his care and skill in his

profession, and constant application when necessary in the way of

his business; and, therefore in justice to his merit, I presume to

recommend him to any one that shall have occasion to employ him.

Given under my hand at Leith, August 10th, 1762. (Signed) "THOS.

GAIRDNER." "I,

Commodore Dirck Janson, commander of the ship "Campbell-town" of the

Edinburgh Whale Fishing Company, in the voyage this season, do

certify to the owners of my ship and all whom it may concern, that

Alexander Macdonald, surgeon on the voyage this season, has

performed his duty with diligence, care, and as far as I know, with

skill in his profession. Certified by me at Leith,

August, 11th, 1762. (Signed) "COMMDR.

DIRCK JANSON."

By November, 1763, and probably at an earlier date, Dr Macdonald had

settled at Fort-William in fairish practice. Among his patients were

Lieutenant John Macdonald of Auchachar; Angus Macdonald of

Achnacoichan; Lieutenant Donald Macdonald in Maryburgh; Donald

Cameron in Boluick; Duncan Macpherson in Maryburgh ; Donald

Maclachlan in Coruanan; Ewen Macphee in Glendessary Allan Cameron at

Blairmachdrine; John Stewart of Forleck; Captain Alexander Cameron,

at Auchnacarrie ; Duncan Cameron, at Muick; Donald Macphee, in

Glendessary James Thomson, merchant in Maryburgh; Marion Wilson,

residing in Maryburgh; Mary Cameron, relict of Donald Cameron,

tacksman of Drumarban; Donald Mackinnon, at Moy; and Donald Cameron,

tenant in Achnasaul.

It will be noticed that the Captain and

Commander, whose name strongly reminds one of a famous character in

"Guy Man nering," does not certify to Macdonald's skill from

personal experience, probably being strong enough to dispense with

any medical assistance, but the doctor's operations on the crew

needed in all likelihood a heavy hand, which unfortunately stuck to

Dr Macdonald. Auchachar and Achnacoichan considered his treatment

and physics improper and dangerous, and being taken into Court for

his account, the former stated in defence that in the autumn of 1764

there was a severe flying distemper over the country, and that he

got alarmed by the appearance of certain blotches. Dr Macdonald

undertook the cure, and dosed him with drugs and physic, so that

from August 1764 to May 1765, he was unable to leave his room,

became emaciated to a skeleton, "more like a ghost than a corporate

body"; that Dr Macdonald ultimately acknowledged he did not

understand the case, and on being challenged for charging at the

rate of 1200 per cent, for his drugs he answered that it was on

account of " his straitened circumstances." Upon proper advice

Auchachar, by drinking goat whey and "Trefoil" tea, gradually

recovered. Achnacoichan's defence was that his son Angus, a boy of

twelve at school at Fort-William, caught the prevailing distemper,

which the father intended to have dealt with according to a recipe

he possessed of his late brother, Dr John Macdonald, but meeting Dr

Alexander Macdonald, the latter offered to treat him gratis, and

applied mercurial and other drugs to such a degree that the boy

became "so enervate and feeble that a kind of paralytic disorder

occurred." Thoroughly alarmed, Achnacoichan consulted the garrison

surgeon, who said that the drugs supplied were too much for the

strongest man, and ordered a radical change. In 1767 Dr Macdonald

removed to Knoydart, where I find him practising in 1771. The last

notice of him is a letter in a shaky hand, and denoting an old,

unpopular, and irascible man, dated, Knoydart, 4th January, 1790. He

had apparently assaulted a neighbour, and I give part of his

explanation. He says—

"I can prove 1st, that the stroke I

aimed at him he never received, so consequently did him no injury ;

2nd, that it was by his repeated endeavours to traduce my character

and his insulting language when I desired to know his reasons for

traducing my character that I made a stroke at him, not with an oak

bludgeon but with an ash stick, which stroke he never received; 3,

that he is of a bad character I can easily establish, and that he

committed theft and depredations on my own property I can make dear,

and that it was after he was found in my garden burthened with my

onions, I said that if I caught him in repetitions of the kind I

would shoot him in the act as soon as a muir cock."

From Fort-William hundreds of emigrants

sailed at different times. Mr Flyter, the well-known lawyer, writing

on the 27th June, 1801, says—

"Your friend Mr Denoon left this on

Wednesday for Nova Scotia on board the Sarah of Liverpool. The

Aberdeen vessel sailed eight days before then, and I hope they will

have a pleasant voyage. Both vessels were as full as they could hold

of emigrants, and many who wished to go could not be received."

In 1805 the state of the earlier

Fort-William Sheriff Court Records was very unsatisfactory, as may

be seen from Mr Flyter's letter now given. It is hoped that the old

papers were at least to some extent recovered. Mr Flyter's letter

dated Fort-William, 18th April, 1805, is as follows :-

I cannot give any account whatever about

old processes or any other Records of this Court preceding the

beginning of February, 1799, the time I came to this country. It

defied me to get a paper except few trifling processes then in

dependence from my predecessor, Bailie Cameron. I often applied both

to him and my constituent for possession of the Records of Court,

but neither paid the least attention to the business. Any process

that occurred in my own time I can easily put my hand on, but

further I cannot go."

A Custom House had been established for

some time at Fort-William with success. Upwards of a hundred years

ago Mr Cohn Campbell, one of the most influential men of the

district, and much respected, was collector. The estate of

Ardnamurchan having changed hands, and the new proprietor, being

energetic and having the ear of those in high places, took it into

his head to try and get the Custom House removed to the Bay of

Kilchoan, and managed to carry matters so far as to enlist the

sympathies of the Board of Customs at Edinburgh. The Duke of Gordon

was furious, and with the Duchess, who took the matter up warmly,

stopped the removal for a time. The natural shelter and other

advantages of Tobermory, though like other Government fishing

villages, failing as a permanently successful fishery establishment,

were such as to give it the preference. Thus, while Riddell failed

in his main object, Fort-William was ultimately sacrificed, having

in its present prosperity, perhaps some consolation in the thought

that its old opponent's descendants have been cleared out of their

temporary possession of Ardnamurchan.

The annexed letter from the Board of

Customs and the report by the Fort-William authorities may be read

with interest at this day. It appears from Mr Tod's letter that

Collector Campbell furnished him with early information, seeing with

his usual sagacity that in Toberrnory lay the danger. I observe that

the Duchess at once applied to Lord Adam Gordon, who then held a

high military position in Scotland, and also to Mr Dundas :-

"Number Forty-six.

"Gentlemen—Being informed that in the

west side, about two miles from the point of Ardnamurchan, there is

a natural wet harbour, that can be made perfectly safe against all

winds at a small expense we direct you to report whether it would

not be more for the benefit of the Public and Revenue to remove the

Custom House from Fort- William to that station, notwithstanding the

objections made by you to Kilchoan, and in particular whether the

officers would not have it more in their power to check smuggling,

especially if a small Boat or Vessel were provided, to be stationed

near the place now proposed, and employed under your direction.

"We being perfectly satisfied of your

impartiality and that no interested motives will have any weight

with you for this information, which is to be transmitted with all

possible dispatch.----We are, your loving friends,

(Signed) "J. H. COCHRANE.

"DAVID REID.

"ROBT. HEPBOURN

"Custom Ho., Edinburgh,

13th June, 1787."

"Number Forty-nine.

"Sirs,—Agreeable to your Honours' orders

of the 13th June instant, we beg leave to report that none of the

officers of this Port, tho' acquainted by frequently sailing the

Sound of Mull, either observed, heard, or had any knowledge of such

a natural wett harbour, as your Honours' mention, previous to the

above Order; further than it late addvertisment in the Edinburgh

newspapers by the Proprietor of his intentions to lett his Estate of

Ardnaniurchan, pointing it out, nor is it laid down, as such in any

map, chart, or survey of the coast, known or seen by us. On inquiry

we are however since informed by some countrymen ; That a Rocky Bank

or Island across the Beach of the Bay of Kilchoan of Ardnamurchoan

and about two miles from the point, forms a Gutt or Strand that with

the highest Spring Tides admitts Boats and small craft below six to

seven foot Draught of Water within that Bank. That the Bank at

present is no security to even these Boats, as a low Land that near

by overflows, without drawing such Boats above water mark on Land,

when they touch the Shore of that Beach, that Bank being open on

both sides at full sea. We are also assured by several shipmasters

well- known on that Coast, and from our own knowledge believe it to

be so, That the whole Bay of Kilchoan of which the foresaid Strand

forms a part, is neither a safe or commodious Harbour for shipping,

known or frequented as such. With several stink Boats in that Bay it

is exposed to near one half the points of the Compass as a Lee

Shore, particularly to the due South, South East, and South West

Winds, nor is it a Roaclsted or proper Inlett or Outgoing that

Shipping frequent or touch at in passing the Sound of Mull, or the

Point of Ardnamurchan ; in such circumstances, or meeting with

Contrary Winds in the Sound, or off the Point, all vessels make for

the safe and commodious harbour of Tobermory in the Sound of Mull,

if be South the point, and when be North the point, for the Harbours

of the Island of Canay (tho' about ten leagues Distant), Isle

Oransay in Skye, or other harbours in that neighbourhood, and so far

as we can learn there is no safe harbour known even for small craft,

on either side of the Mainland of Ardnamurchan within many miles of

the point thereof. On that footing we humbly apprehend engineers or

professional men in such undertakings can only say the expense of

making such a wett harbour perfectly safe, or estimate the sums

necessary for quays or such artificial bulwarks on that beach as

will effectually secure it a safe harbour for shipping.

Referring to our former report to your

Honors of the 19th December last, stating our opinion of the

advantages or disadvantages to the public of establishing a Custom

House at Kilchoan. The trade and business at Fort-William, and our

sedulous endeavours to check smuggling from thence, are so

well-known to your Honors and appearing by our various quarterly and

yearly returns to the respective offices under your Honourable

Board, it does not become us, so nearly interested in the issue, to

press our opinion further, how far it would be more for the benefit

of the public and revenue to remove the Custom House from

Fort-William to any part of the Sound of Mull. We entreat your

Honors to refer to others not concerned in the proposal from views

of interest, private motives or local attachments, impartially to

certify that point. We trust it will thereby appear to your Honours,

on every prospect and view of the case, that the Port of

Fort-William should not be totally abandoned, or the whole offices

thereof removed to a station about 40 miles distant from so large a

tract of country as ]yes behind, that has now, and of a long time,

felt the benefit of that establishment. But we pray leave to declare

it as our avowed and decided opinion, that if, it is thought fitt to

be so removed to any part of the Sound of Mull, Tobermory should be

the station as most eligible in every respect for every purpose of

the Publick and Revenue, and not the Bay of Kilchoan or any part of

the country of Ardnamurchan where from what we have already stated,

we assuredly apprehend it could answer no publick view whatever.

"We submit to your Honours what services

a few Custom House Officers could render the public, stationed on a

Point of land surround by the Ocean, without a Harbour on that land,

secluded by inaccessible roads for about 24 Scots Miles from even

the small village of Strontian, as the nearest post-office of it

Weekly runner ; where neither the Proprietor, a Civil Magistrate, or

other man of business at least known in Trade, Manufacturer, or

Merckantile line, presently reside, without troops nearer than

Fort-William to assist them, and tho' a vessel was provyded to check

smuggling under such Officers' Directions as that vessel could only

in moderate weather touch at, or near the Station of these Officers,

and in our opinion, should more properly be stationed or lye at

Tobermory with any view of success. It does not occur to us that

under these circumstances, the Officers at Kilchoan or such vessel

could easily give the necessary intelligence or assistance. And we

have said in our former report how unfltt in our idea, a small open

Boat is to navigate those Seas for the use of the Revenue but in

Moderate or Summer weather.

"In a case of this importance to the

public we humbly conceive it to be our Duty to state fully the facts

as strike us, and humbly hope they will be confirmed to your Honors

as such by the impartial Public at large, and more particularly we

beg leave to appeal as to the grounds on which we found our

Observations to Captains Crawford, Campbell and Hamilton as

Commanders of the Revenue Cutters on that Station and professional

gentlemen best informed on the Coast, and to the fishing Traders of

Greenock, Campbelltown, and Ohan, who had every access to consider

the case with attention which is humbly submitted.

"We have the Honour to be with much

respect, Honoured Sir, Your very Obedient hum. Servants, (Signed)

"COLIN CAMPBELL., "DUN. AL. BAILLIE.

Customs Ho., Fort-Williarn,

"26th June, 1787."

"Fochabers, 4th July, 1787.

Sir,—As I am uncertain at present where

to address a letter to the Duchess I beg you will take the trouble

of forwarding to Her Grace the enclosed copy of a late

correspondence between the Board of Customs and the officers of the

Custom House at Fort-William, concerning the removing of the Custom

House from that place to Ardnamurchan.

"As the very existence of the village of

Gordonsburgh depends upon the Custom House being continued there,

please inform Her Grace of the necessity of her making every

possible exertion immediately to prevent Sir James Riddell's plan

from being carried into execution. And it will also be proper while

Her Grace has access to the Treasury Board and the several gentlemen

of the Customs about Edinburgh, that she enter a caveat against the

removing of the Custom House at any future period from Fort-William

to any of the intended fishing towns, particularly to this same

Tobermory which perhaps there is some reason to be afraid of as the

rival of Gordonsburgh.

You know what steps it may be necessary

to take at Edinburgh to prevent the Board of Customs and the

Exchequer from coming to any decision till Her Grace arrives.—I am,

sir, your most obedient servant,

(Signed) WILL TOD.

To Cha. Gordon, Esq. of Cluny, etc.,

etc. CAMERONS V.

MACDONALDS, et e contra.

The hereditary ill-feeling between those

surnamed Cameron and Macdonald is well-known. It is not, however,

often mentioned in black and white. Before giving the instance alter

referred to, I may refer to the claim preferred by the Carnerons to

be placed on the right at Culloden. This was directed against the

Macdonalds and is thus alluded to in an exceedingly modest but clear

account of the Rising of '45 written by Lieutenant-Colonel Donald

Macdonell of Lochgarry. It will be recollected that John Macdonell,

then of Glengarry, was an old man, and his eldest son Alexander

being taken captive before the Rising actually took place, and

detained prisoner until it was over, was prevented from taking the

field. The clan was therefore in two divisions, led, the one by

Lochgarry, old Glengarry's near relation, and the other by the

latter's younger son, Angus, accidently killed at Falkirk.

I have recently been favoured by my

highly valued friend and ancient ally Mr Macdonell of Morar, with

the perusal of an old manuscript bearing to be a "Memorial by

Lochgarry for Glengarry." It gives a full account of all that

occurred to Lochgarry, one of Prince Charlie's earliest supporters,

up to his embarkation for France. The I\IS. is not only signed by

Lochgarry but is apparently in his handwriting, and is of such value

as calls for its separate publication. The Northern Macdonalds had

become divided into four distinct families, Glengarry, Clanranald,

Sleat and Keppoch, who, though sharply divided among themselves, had

been up to this period steady loyalists. Now alas ! for the first

time the house of "Donald Gorm, clann Domhnuill naiz Eilean,"

appeared not with their brethren. Lochgarry, it will be observed,

according to the after-quoted narrative, refrained from giving Lord

George Murray's reasons for his unfortunate determination, as if

Lord George desired the place for his own men. These reasons,

however, have been given by himself. He could have had no object

except to what was right, unless high expediency. The major blame

undoubtedly lies at the door of Lochiel, who asked what he was not

justified in asking, and that too at a very critical moment; while

on the other hand Lord George was by this time well aware of the

extreme jealousy and exalted punctilio that existed between the

Highland chiefs, amounting almost to religious fanaticism. Lochgarry

says— "The

Macdonells had the left that day, the Prince having agreed to give

the Right to Ld. George and his Atholmen, upon which Clanronald,

Keppoch and I spoke to his R.Ils. upon that subject, and begg'd he

would allow US our former Right but he intreated us for his sake we

woud not dispute it as he had already agreed to give it to Lord

George and his Atholmen, and I heard H. R. Hs. say that he repented

it much and would never doe the like if he had occasion for it. Your

Regmt that I had the Honr. to command at this battle, was about 500

strong, and that same day your People of Glenmorrison were on their

way to join us, and likewise about Too Glengarry men were on their

march to join us on the other side of Lochness. Att this unlucky

battle, we were all on the left, and near on our Right, were the

brave Macleans who would have been about 200, as well looked men as

ever I saw, commanded by Maclean of Drumnine, ane of the principal

gentlemen of that Clan; he and his son were both kill'd on the spot,

and I believe 50 of their number did not come off the field. Their

leader waited of the Prince on his landing, with a commission from

most of the principal Gentlemen of that Clan, who were always known

to be among the first in the field when the Royl family had to doe,

and wou'd have been all in arias at this time, had not been the

unlucky accident of their Chief's being in the Government's hand,

which was a cruel loss to the cause, and occasion'd that this brave

Clan were not all in the field they live likewise under the

jurisdiction of the Duke of Argue, since the Forfeiture of their

great Estates, occasioned by their constant attachment to the Royll.

Family so consequently live in the neighbourhood of the numerous

Clan of the Campbells, who were always dissatisfied to the Royll

Cause, and if they had all arisen in arms their familys wou'd have

been ruin'd by them, but if their Chief had been at their head, this

they would have little regarded. However, I'm sure, including the

200 at Culloden and those Lochiel had out of Swynart, and other

parts, with several other young gentlemen that had joined the

severall Regmts. of the Macdonells, vou'd have compleated twixt four

and five hundred men of that Clan."

Lochgarry's reference to the gallant

Macleans, though it does not bear upon what I am writing about will,

I know, be excused.

The object of the memorial was, no

doubt, to let Glengarry the younger have a full and direct account

of the behaviour of the clan.

Barisdale was so unpopular with the

Camerons that, without the slightest warrant or authority, they took

it on themselves to deport Coil Macdonell, third Barisdale, and his

son Alexander to France.

My immediate illustration relates to

people, who, though in a humble position, may be expected to throw

greater keenness and personality into a struggle than their

superiors.

There were two small possessions in Kilmonivaig, Donie and Auchcar,

names fallen into desuetude, on the old road by the water of Lundy,

passing Lienachan and others, which joined the Glen Nevis road at

Poulin More before it reached Loch Treig. Upon the 1st of April,

1780, Donald Macdonell, late volunteer in his Grace the Duke of

Gordon's North Fencibles, now tacksman of the fifth part of the farm

of Auchcar, his said Grace's lands in the lordship of Lochaber, says

that he had the honour of his Grace the Duke of Gordon's

acquaintance and his good countenance, for whom he had recruited for

his regiment five men, four being Macdonalds of his own friends, and

the fifth an Irishman, and that he, Donald, having a throng family

of six "wake" children, had to give up soldiering, when he was

discharged by his Grace, and a letter of tack for the fifth part of

Auchcar given him.

A minute account is then given by Donald

of his enjoyment with friends of his pipe and glass in the house of

Donald Kennedy, in Maryburgh, on the evening of Friday, 24th March,

1780, when the company were intruded upon by Donald Cameron, tenant

in Donie, who used violent language and assaulted them, threatening

Donald thus "Donald Duke, for all your great friends, Duke of Gordon

and Macdonells, if I get you by yourself, sooner or later, I'll beat

you so that you will not be able to travel the road. The principal

charge against Cameron is given in Donald's own words. It is—

"That on Saturday the twenty-fifth day

of March last, being the day following the encounter in Kennedy's

house, when the memorialist and a neighbour were upon the road to

Inverness, and had gone about three miles out of Maryburgh, the

memorialist having looked behind him he observed the said Alexander

Cameron and Donald Cameron, his brother, coming after him with a

speedy pace, and the memorialist then dreaded, from the hurry and

appearance they had and from the information he, the memoralist, had

got the night before, that the said Alexander Cameron was

threatening to use him ill, and putting him from walking the road,

the memorialist and his neighbour having qot into a hollow part,

they vent off the road and shifted their course so as to avoid the

said Alexander Cameron and Donald Cameron, and having gone round a

knowe, the memorialist was greatly surprised to see the said

Alexander and Donald Cameron take a short cut and run both up

towards the memorialist, and no sooner had the said Alexander come

up to him, but he drew his large oak staff and made a stroke at the

memorialist's head, which, if he had received, would have

undoubtedly killed him, but was avoided by the memorialist running

off, and the stroke only touched him in the heel. The said Alexander

then pursued and struck the memorialist with his staff on the crown

of the head, cutting him desperately, whereupon the memorialist,

seeing he could not then escape, grappled with Alexander Cameron,

and they two were allowed a considerable time to pull, haul, and

strike at one another—the memorialist had no staff, and received

many strokes from Alexander Cameron on the head with his staff,the

marks of which are still visible—the memorialist having then by

chance got above Alexander Cameron, was seized by the two legs by

the said Donald Cameron in Donie, the said Alexander's brother,

trailed off him, and Alexander put above him, and the said Alexander

having kneed the memorialist, who was all covered over with blood,

was allowed to get up with life only in him, being by this time much

hurt and faintish; that the said Alexander is a bad member of

society, and universally known in the country as a quarrelsome and

disorderly person, much given to fighting."

Donald concluded by alleging that the

attack was premeditated, and occurred upon the farm of Torlundy, at

a place calle'l Glackvirran, and he being "a poor man with a throng

family, of the family of Keppoch," trusts that all well disposed

persons will contribute to see that he gets justice, seeing the said

Alexander and Donald Cameron have expressed no regret for their

conduct and no excuse, except that the memorialist "was a Macdonell,

to whom they seem to have an utter aversion." The Camerons were

bound over to keep the peace in the sum of one hundred inerks each.

AN OLD MAP OF MAMORE.

In 1803 there was prepared for the Duke

of Gordon a hand map of Lochaber for convenient use and reference.

It was drawn out by a Mr Clinkscale, either connected with the

garrison, or more probably a schoolmaster. It is not to any scale,

but being only a few inches square, it is very handy and useful,

containing the names and situations of every place on the Gordon

estates, as well as the roads.

These may first be referred to, and are

of a twofold character. "The dotted lines ........are all good and

passable roads. The roads denoted by single lines, are generally

footpaths, but may be travelled on horseback." So the plan states.

Taking Fort-William as the centre, a good road follows the shore of

Loch Linnhe as far as Inshrigh, and Ardgour Ferry. The old King's

road to Glasgow still remains as it then was, by Achintore Mar, and

Blarmafoldach to the head of Loch Leven. Before reaching the house

of Kinlochlevcn, a minor road struck off to the northeast, by the

foot of Loch Eilt to the north of Loch Treig, and to Fersit, while

the Glenevis road followed the water until it emerged beyond

Craiguanach and joined the last mentioned road north of Loch Treig.

The main road from Fort-William to the

east and north, by Inverlochy and Torlundy, made for High Bridge,

then divided into two branches, one continuing in the same direction

to Low Bridge and the Ratulichs, where it again divided, one branch

leading by the sides of Loch Lochy and Oich to Fort-Augustus, the

other through Glengloy to Leckroy. The other branch of the main road

from High Bridge passed the two Blarours, Tirindrish and Achaneich,

making for Glenroy, but for some time keeping a considerable

distance from the water, and then joining the Glengloy road at

Leckroy. No other road of any kind is shown except the above two,

north of the Spean. A minor road led from Torlundy by Leanachan and

Corrichoille, ultimately at Poulinmore, joining the Glenevis road

before mentioned, and, finally, there was a minor road westward

south of the Spean beginning at Inverlochy, keeping close to the

River Lochy by Camisky and Lindallie to the old church of

Kilmonivaig, at the junction of the Rivers Spean and Lochy, thence

by the Spean to High Bridge, Unachan, Killichonate, Inch, Clinaig,

Monessie, Achnacoichan, and Inverlair to Fersit. There is not a

vestige of road shown on Mackintosh's side of Glen Spean, and of

course Roy Bridge did not then exist. There was a ford over the Roy,

just as it fell into the Spean, and another across the Spean at

Inch, both very dangerous. At the former, Juliet or Shiela Macdonell,

the Keppoch poetess, was drowned.

Mr Clinkscale was evidently a man of

taste, and denotes the natural woods, in particular "the fine oaks"

of Tirindrish. Other wooded places marked are above Leckroy, to the

east of Loch Treig, Achnacoichan, Inchrigh, and Culchcnna.

Centuries ago the sea washed the walls

of Inverlochy Castle, and I possess a fine engraving showing a

galley of some size swinging at anchor below the castle, having one

prospect of still waters—the sea. At one time the huge moss of

Corpach must have been covered with water, partly by the sea and

partly by the overflows and siltings of the Lochy.

OLD RIGHTS OF FISHING AND FLOATING ON

THE LOCHY. I

have frequently alluded to the beauty of the valley of the Ness

before the Canal operations, and I can imagine the valley of the

Lochy must have been at one time equally peaceful and beautiful. The

River Lochy before the Canal was made, flowed easily and naturally,

by the plain of Dalmacomer, soon after joined by the Spean. On its

south side, the ancient Church of Kilmonivaig, on a fine terrace,

looked down upon the plain, the meeting of the waters, and the

picturesque old burial place of the Macmartins—Cill-'ic-Comer. Now

matters are entirely changed ; the surface of the loch hs been much

heightened, and the Canal itself, except for the masts and sails of

vessels or the cheerful funnels of steamers, is by no means an

object of beauty. The fishings in the Lochy have been greatly

interfered with, and the three "F's," so much in evidence recently,

were not unknown in Lochaber 70 years ago, when Lochiel claimed from

the Canal Commissioners compensation for fishing, floating, and

ferrying disturbances on the Lochy.

Before referring to these, I wish to

notice the cruives in the river which had been set up by the Duke of

Gordon and Lochiel, then for a wonder, in alliance as regards their

rights of fishing. In 1797 Alexander Macdonell of Glengarry alleged

that these two gentlemen had established cruives in the river Lochy,

and interdict was sought against him to deprive him of his rights as

an upper heritor and user of the river for floating timber and other

purposes.

Glengarry taunts the Duke for his ignorance of the law, as brought

home to him in the case of the upper heritors of the Spey, where his

Grace's obstacles to navigation or floating were declared illegal,

and also that it had been similarly decided in the case of the Ness.

One or two points of interest came up in course of the proceedings—

"That while yet the manufacture of wood

in the country was in its infancy, the firwoods of Glengarry

attracted the attention of strangers, more than a century ago a

smelting furnace was erected near Invergarry on account of the

quantity of charcoal which the wood afforded, and the transportation

of timber to the West Coast was carried on upon a large scale. There

is yet the trace of the Canal which was then formed betwixt Loch

Oich and Loch Lochy for the conveyance of the timber, etc., which

afterwards was floated down the river to the sea. The practice which

has taken place since, is comformable to it, for not only has the

firwood of Lochiel been in use of being floated down the river Lochy,

but also the firwoods of Glengarry without interruption. For

instance, the only ship built at Fort-William was made from the

Glengarry firwoods, and was called 'The Lady Glengarry' on that

account, and most of the houses at Fort- William are built of timber

from the same woods. The river Lochy is well calculated for the

purpose of water carriage from the interior into the sea. On Loch

Lochy itself there are several large boats, and it has depth enough

for the Royal George to swim in. The proprietors of Kilmonivaig have

been in the use of keeping a boat upon the river below the Loch, and

there are many instances of boats even going up the river, much more

coming down, for different purposes of utility to the inhabitants,

so that it is much more calculated for use than the river Spey,

whose rapidity renders it less capable.'

Glengarry was successful, and the

cruives, apparently more insisted on by the Stevensons, the salmon

fishing tenants, than the proprietors, were discontinued. The

opening of the Canal changed the question of floating, and Lochiel,

in 1834, appears on a different tack. He could of course get his

woods carried to Fort-William but he must pay at least dues, if not

also freight. Some of the farms along the course of the Canal were

deprived of access to wonted roads, banks leaked, culverts became

choked, and over all grounds were permanently flooded by the raising

of the level. Lochiel accordingly claimed large compensation. Hugh

Robertson, wood merchant, stated in support of the loss of floating,

that he paid not only canal dues, but that for pulling floats

through by boat he got 3s a ton more than he used to receive as a

floater, and that the new cut of the river at Gairlochy practically

prevented floating, except at special times. As to the claim for

loss on fishings Mr Charles Cameron, at Cuichenna, stated that

salmon did not now go up the new cut at Gairlochy, that he had seen

numbers trying to get up, but were unable to get over the fall. That

Lochiel's fishing was an excellent one, the witness having

frequently killed two or three salmon before breakfast. The salmon

spawned in Lcch Arkaig, and went up the rivers at the head of the

lake. That by the fish not getting up to the spawning ground, loss

has arisen, not only to the Lochy but to the Arkaig fishings. Other

witnesses stated that the ferry rents fell off greatly since the

canal was formed, as there was no crossing the Canal formerly except

at Banavie. The sum ultimately agreed upon and paid in name of

damages and compensation was close upon £5000. This was over and

above the large sums originally paid at the formation of the Canal.

LOCHABER LITERARY MEN, PAST AND PRESENT.

No part of the country has during the

present century more steadily produced its quota of literary men

than Lochaber. During the early part Mr Maclachian was preeminent.

After him may be mentioned Mr James Munro, and Dr Macintyre of

Kilmonivaig, Dr Clerk of Kilmallie, and ahead of all others stands

the evergreen Dr Alexander Stewart of Nether-Lochaher.

"May he live a thousand years."

Mr Maclachian was fortunate in being

warmly supported by the influential county gentlemen of his day. He

had the knack of pleasing them and exciting the affection and

attention of their children, his students. I have many of his

letters and some of his Gaelic hooks, including his copy of

Alexander Macdonald's Gaelic Dictionary of 1741, with copious notes.

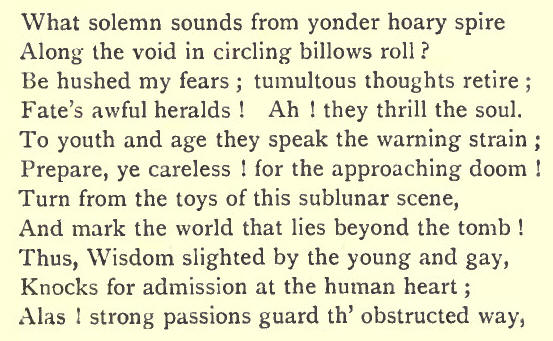

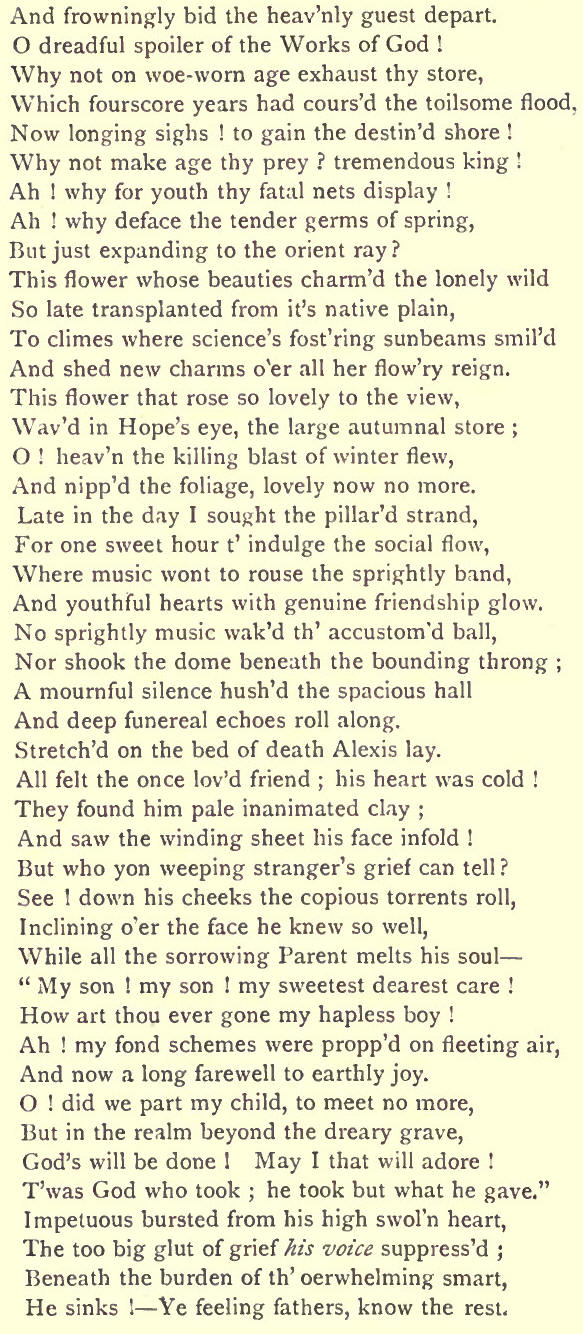

From his papers I select part of an elegy on a young student, Alexis

Sinclair, as a fair specimen of his style. It has not, I think, been

published, though not having a copy of his works beside me, I cannot

be certain. The death would have been about i8o6, and the youth was

probably a Caithness boy. It is as follows—

AN ELEGY UPON ALEXIS SINCLAIR.

THE DISMEMBERMENT OF INVERNESS-SHIRE IN

LOCHABER. The

county of Inverness, and particularly the parish of Kilmallie, has

suffered much from the high handed dismemberment effected by Lord

Lorne in 1633, cutting off from Inverness-shire the districts of

Ardgour, Kingair]och, Morven, Sunart, Ardnamurchan, and their isles.

At that time the Argyll family seem to

have been superiors of what may be strictly termed the barony of

Lochiel, reputed a £30 land. Not only was the dismemberment

objectionable, but it was gone about in an extraordinary manner.

Attempts have been made of late years to rectify some of the

absurdities, and even at this moment there is a point as to the

proper designation of proposed new parishes, North and South

Kilmallie being suggested, though geographically incorrect. Perhaps

the best solution would be to have Kilmallie in Inverness-shire

alone, the remainder to be called Ardgour.

The barony of Lochiel extended from

Glenlinnon at the south west to Banavie at the north east; the towns

of Banavie and Corpach being the last enumerated in the older

titles. This is a fine stretch of water frontage, but, except at

Fassifern, is narrow and overlapped at the back by Glen Pean, which

stretches almost to the head of Loch Morar. Lochiel estate proper

was small in comparison with Glenluie and Loch Arkaig, and it was

little wonder the Camerons struggled hard for possession of the

latter. As it now stands, extending from Loch Eil to Loch Quoich and

to the upper waters of the Garry, no finer estate is found in the

Highlands. If

one looks at the ordnance sheets he will find that the boundaries in

Lower Glenluie have been fixed arbitrarily, absurdly, and with

disregard to all natural rules. The important township of Musherlich,

with its adjunct of Tor Castle, was detached from the county of

Inverness and the property of Mackintosh, who in vain protested

against the spoliation. This proceeding was acquiesced in by Lochiel,

being a handle against Mackintosh. After the enforced sale, when

Argyll and Lochiel well knew that their acts would be closely

scrutinised and advantage taken of any flaw, they were in a dilemma

as to how Musherlich would be treated in the deed of conveyance. If

inserted with Mackintosh's other lands, it would be tantamount to an

admission that all the actings since 1633 had been tainted and

vitiate; while if not inserted, it would be open to Mackintosh to

raise the question that Musherlich was not included in the sale, and

that he was entitled to reclaim it. The Argyll lawyers dealt with

the point very judiciously. Musherlich was included in the

disposition as for greater security only, the Earl alleging that it

was already his property, and it was further conditioned that the

then Mackintosh should retain the designation of "of Tor Castle,"

which he was then known by, during his life.

Lachlan Macdonald the last designed of

Tor Castle died in 1702.

RENTALS OF GLENLUIE AND LOCH ARKAIG IN

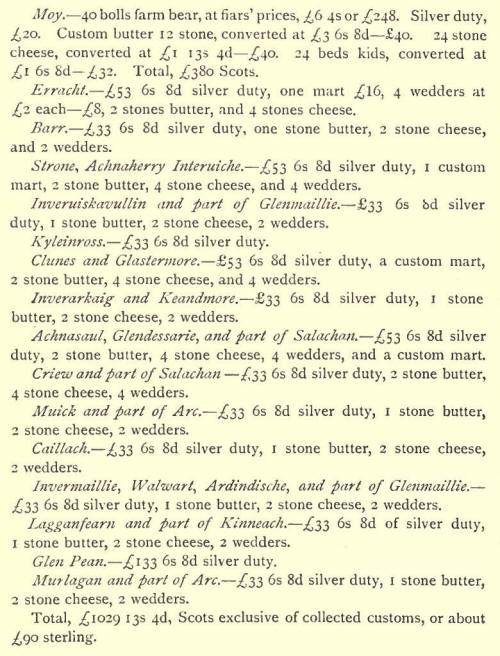

1642. I now

give a rental of Glenluie and Loch Arkaig in 1642. First the

tenants' names, and second the rents—

NAMES.

1. Ewen Cameron of Lochiel in Moy.

2. Donald Cameron, Tutor of Lochiel.

3. Ewen Cameron, alias Bodach in Erracht.

4. Ewen Vic Allister More.

5. Donald Vic Coull Vic Allister in Barr.

6. John Dhu Vic Coil Oig in Strone.

7. John Vic Coil Vic lain Vic Conchie in Inveruiskavullen.

8. Duncan Macmartin of Letterfinlay in Kyleross.

9. Duncan Vic Allan Vic Ewen in Clunes.

10. I)uncan Roy Vic lain Vic Allister in Inverarkaig.

11. lain Vic Conchie Vic Ewen in Achnasoul.

12. Allister Vic Conchie Ban in Criew.

13. Ewen Oig Vic Conchie Vic Ewen in Muick.

14. Mulmor Vic lain Vic William in Caillach.

15. Lachlan Vic Coil Vic Gillonie in Keandpol.

16. John Vic Coil Vic Allister in Invermaillie.

17. Ewen Vic Conchie Vic lain in Lagganfearn.

18. Duncan Vic Even Vic Aonas in Glendessarie.

19. Donald Vic lain Dhu Vic Gillony in Glen-Pean.

20. John Vic Ewen in Murliggan.

They are described as "kinsmen and

followers of the said Evan Cameron, and principal tenants,

occupiers, and inhabitants by themselves and others in their names

of Glenluie and Loch Arkaig, and particular towns thereof

respective."

RENTS.

EILEAN-'IC-AN-TOISICH, AND THE CLUNES

LANDS. The

following is an extract from the Mackintosh History:-

"In the year 1580 Mackintosh, for

curbing the insolency of the Lochabrians, caused build a little

island in the wester end of Loch Lochy, which was called Eilean

Darroch, or the Oaken Island, for that it was built on oaken jests

within the water. He had 2500 men for 3 months' time in Lochaber

while the island was a building, and by means of this island

(wherein he kept a garrison) he brought the Lochabrians in

subjection to their superior; but how soon that island was surprized

and demolished, the country people brake forth again to their wonted

rebellion."

Having frequently tested without blot the accuracy of this history,

I many years ago, when I had occasion to be frequently in Lochaber,

enquired as to this island, but without any result. One day,

however, the late Colonel Cameron of Clifton Villa, Inverness, of

the historic family so long in Clunes, asked me if I ever heard of

Eilean-anToisich, or sometimes called Carn-'ic-an-Toisich, to which

I replied that I had not only heard of it, but had been long in

search of it, and hoped now to know where it was.

Colonel Cameron then informed me that in

his youth, on a remarkable clear day, being in a boat in the Bay of

Clunes along with a very elderly man, full of tradition, the old man

bade him look closely towards the bottom, when he observed several

large hammer-dressed stones, as also logs of timber like joists. He

was further told, that before the canal operations these remains

were often visible on calm days, but since then only occasionally,

and the old man had himself been informed by older people, that that

was all now remaining of an artificial stronghold put up by the

Mackintoshes to keep the people in order, hence, Eilean or Cam-an-Toisich.

Colonel Cameron told me that the wood he saw was very likely oak. He

farther stated that as the level of the loch had been much raised

since the occasion, he doubted whether now it was possible even on a

calm day, and otherwise suitable, to see anything. Finding that I

was much interested and that he himself had for the first time

learned the object of the structure, Colonel Cameron was good enough

to say that perhaps some day we might make a pilgrimage to the spot,

for he thought he could come very near it. Though not the eldest son

of Allan of Clunes, his father had put the Colonel's name into the

lease along with his own at the settlement with Lochiel in 1834, and

were it not that the Colonel was on active service when the lease

expired in 1853 he would never have given up the place to which he

and his family were passionately attached.

I have now almost given up any hope of

examining the Bay of Clunes, and indeed without the local knowledge

of Colonel Cameron, any search for the remains of the island would

probably be unavailing.

The raising of the loch has caused the disappearance of many other

landmarks on the shores of Loch Lochy, and notably much of the road

on its west side. Being now chiefly forest, neither Lochiel nor

Glengarry have any interest in its maintenance or in re-forming it

where submerged, but it long served the extensive and once populous

territory from Laggan Achindrom to Inverie prior to 1834.

LOSS OF GLENLUIE AND LOCH ARKAIG BY

MACKINTOSH.

Allan Cameron of Clunes stated that "from the river Arkaig to

Goirtean-na-Croigh, including all the arable land in that space,

viz., 12 acres at Bun Arkaig ; 15 at Clunes, viz., Chef,

Inverbuiebeg, Inverbuiemore, and Goirtean-naCroigh, and about

twenty-three acres of pasture, in all about 50 acres, had been

submerged, besides a space of about 4 miles, averaging 30 yards in

breadth to the Lochiel and Glengarry march at Derragalt, with stumps

of trees standing out of the water. It was along this road that the

Macdonalds marched on their way to the battle of Blar-nan-leine, and

that Prince Charles two hundred years later, after a few hours' rest

at Invergarry Castle, moved westward the day after Culloden. By this

road also Mackintosh, for the last time, marched in force to

Lochaber to meet Lochiel, who was waiting in arms to stop his

passage across the Arkaig. A few words from a contemporary writer,

personally present on the occasion, may not he without interest.

Mackintosh had rendezvoused in Stratherrick and—

"On Saturday, 16th September, 166,

marched through the wood of Glastermore to the Clunes, a room

belonging to Mackintosh, and upon their approach Lochiel and his kin

drew themselves and all their cattle and goods to the south side of

the water of Arkaig, a great water, not possible to get over but by

boat and one ford which the enemy had guarded, resolving to keep the

water between Mackintosh and his forces, and them. Now you are to

know that the water of Arkaig being a mile long, which runs out of a

loch that is 12 miles in length called Loch Arkaig, into another

loch called Loch Lochie, and this water not being passable but by

one ford, as said is, it behoved Mackintosh, who had no boats, to

march about both sides of Loch Arktig, 24 miles, before he could

come at the place where the enemy was encamped."

They proceeded as far as Achnasaul, but

in the meantime communings took place and Mackintosh and his people

fell back on i8th September, encamping before the island of Loch

Arkaig. The writer continues that upon the 19th of September—

"Mackintosh marched to the Clunes where

there was a minute of contract drawn up and subscribed by both

parties wherein Mackintosh was obliged to sell his lands of Glenluie

and Loch Arkaig to Lochiel or any other person he would nominate,

and Lochiei did engage himself and six of the specials of his

friends under great penalties to pay to Mackintosh the sum of 20,500

merks on the 12th day of January next thereafter, within the town of

Perth, and on the aforesaid day also to secure him sufficiently for

the remainder of the sum (72,500 merks) to the satisfaction and

content of any such persons of Mackintosh's own choosing, and the

terms of payment to be Martinnias 1666 and Martinmas 1667. Upon the

20th September, 1665, Lochiel having crossed the water of Arkaig,

Mackintosh and he met (24 men on each side) upon the lands of Clunes,

and having drunk together in a friendly manner, in a token of

perfect reconciliation, exchanged swords and so departed, having in

all probability at that time, taken away the old feud which, with

great hatred and cruelty continued betwixt their forbears for the

space of 360 years. That afternoon Mackintosh and his people marched

in order from Clunes to Laggan Achindrom, where after many friendly

embracings, the forces of Badenoch and Braemar take leave of

Mackintosh and the rest of the friends, and that friendly little

army disbanded in peace."

The feud was ended, but naturally there

was but little friendliness on either side, and for upwards of 200

years-until 1869—no Mackintosh visited at Achnacarry, nor did a

Lochiel set foot within Moyhall.

LOCHEIL. - ENORMOUS INCREASE OF RENT.

The subsequent history of Glenluie and

Loch Arkaig, subsequent to the purchase by Lochiel, is little known.

After the forfeiture of 1715 they were claimed under the Superiors

Act by Argyll, but were afterwards restored to Donald Cameron the

younger, who in 1745 was the undisturbed owner. Circumstances and

the popular verdict have been very favourable to the character and

position of the Lochiels since then.

The estate and clan are inseparably

mixed up with Prince Charles, but there is no denying that to the

heroism and devotion of the people is due the high place acceded to

the family ever since and now. The estates were administered by the

Forfeited Estates Commissioners until 1784, and though their factors

were partial and biassed against the smaller occupants, upon the

whole the rents were moderate. It is said that, like other chiefs,

the Lochiels when exiles regularly received part of the rent. When

such conduct is reported, it is always commented on as extremely

honourable to the tenants. So it was, but let it be recollected that

in former times, rent in the form of money was a minor, easy

consideration—the real burden or tax being services, especially the

liability to be called out to fight at any moment. And this burden,

so often involving the lives of the bread winners, had become almost

intolerable. Therefore the continuous absence or exile of the chief,

after the law became generally operative and protective of the

people, was really no hardship to them—rather the contrary—and this

enabled them to pay a double rent now and then with comparative

case. There is

every reason to believe that the Commissioners did not overburden

the tenants of Lochiel in the matter of rent, and of this Mr

Alexander Mackenzie in his History of the Camerons gives a strong

illustration in the case of Erracht. In 1779, a few years only of

the current lease at a rent of £22 10s, remained, The elder Erracht,

Donald Cameron, second in command in the '45, applied for a renewal,

and this was agreed to, at a rent fixed by the estates factor, Mr

Henry Butter, who fixed the new rent at £48 9s 9d, but on a strong

remonstrance from the tenant the increase was restricted by £3 9s

9d, with a 41 years' lease, whereof the rent for the first 21 was to

be £25, and for the remaining 20, £45 beginning as at Whitsunday,

1781. By this time the craze for sheep farms had set in, and at the

restoration of the estate to Donald Cameron of Lochiel, in 1784, was

in full force.

I shall now give the rental of Lochiel in 1788 from Mr Mackenzie's

History, distinguishing Glenluie and Loch Arkaig from the other

lands. The total is there said to be £1212 9S old sterling, which

Lieutenant Cameron of Lundavra thinks too low, and says, giving farm

by farm, that the estate was worth £2665, or more than double, and

in token of his sincerity he more than doubles his own rent.

The rentals of 1642 and 1788 may be

contrasted with advantage and the rise was by no means high, while

the number of tenants holding direct of the landlord had increased.

It has been said that the increase of rent was owing to the late Mr

Belford, but this is quite erroneous. Mr Belford has enough to

answer for in his dealings with the Dochanassie people in

Glenfintaig. The mischief was done in the time of the restored

Donald Cameron of Lochiel, and

at an early period in his career. Mr

Belford only acted as factor for but a very few years for this

Donald, his chief sway being from 1833 to 1859, in the time of the

second Donald Cameron, a very different man from his father, as will

be hereafter seen. It would be going into invidious detail perhaps,

not the object of these papers, to give farm by farm, the oppressive

doings on the estate after its restoration.

Its restoration, under burden of debt of

£3433 9s id 5-I2ths, though humanely meant in this and other

instances, in the case of Lochiel, the object being personally

unworthy, proved fatal to the people. At the restoration Donald

Cameron was only 15 years old, had been loosely and and

extravagantly brought up, trained abroad, in habits and feelings

having no sympathy with or pride in the family traditions or the

prosperity of his people. Indeed he never visited Lochaber until

1790. He was much in debt before his majority, and deeply involved

in connection with the Erracht sale and subsequent reduction. Ewen,

afterwards Sir Ewen Cameron of Fassiefern, fought his battle with

skill and determination, continued by his son Sir Duncan, up to

Lochiel's death in 1832. But what could Fassiefern do? Money had to

be found, and as early as 1793, by a new set of the estates, the

rental was grievously increased. Heritable debt, family provisions,

and the expense of building Achnacarry House mounted up to so large

a figure that the trustees justly became alarmed, and the estate,

already under trust, was put under entail and thus saved from

extinction. At

the first set most of the old Cameron tenants became bidders, many

of them officers on half-pay, who, by taking advantage of high

prices, and changing the old system into sheep farming, were for a

time enabled to pay their large rents. But what about the people,

the life blood of the clan! They were no longer wanted. On the

contrary, they were in the way, and, practically starved out, were

glad in large numbers to enlist in Erracht's regiment. The sheep

farms wanted but few hands, old cultivation fell out, and houses

fell into decay. The people gladly enlisted with Erracht, but it was

necessity, which has no law, that compelled the balance of the

people to enlist and serve in the Lochiel Fencibles in 1799-1802.

All his life Lochiel was in straits,

selling his woods to that extent that Sir Duncan Cameron had to save

the woods on Fassiefern by paying for them, leaving them to stand,

for which he was repaid by the next Lochiel, a most honourable man.

Soldiering was over in 1815 ; then the

Canal operations began and for some years gave employment, when many

of the people got lots at Corpach, Banavie, on the flosses of Gaol,

Lochyside, etc., where they still are, and this was the fate of the

descendants of the gallant and warlike supporters of Lochiel !

Starved out of their valuable farms and grazings in Glenkingie,

Glendessary, Glen Pean, and others, most of the warlike and spirited

race, the followers of Lochiel who remained in the country had to

take up their home in the moss of Corpach, and in future, in the

circumstances, to depend on mere casual manual labour for

subsistence. That there was, at the time, fair demand for labour was

most fortunate.

A few instances of the rise in rent will suffice—

I. Clunes.—By the rental of 1788, Donald

Cameron, a most worthy Highlander, paid a rent of £48. Allan Cameron

of Lundavra, values Clunes at £180. Now at the first set in 1793,

the rent of Clunes was pretty stiffly raised from 448 to £110 7s 4d,

upon one of the finest and oldest clansmen of Lochiel. He was on

half-pay, and thereby, with close attention and natural cleverness,

was able to exist and show that hospitality so peculiar to the

family of Clunes, having had the special honour of Prince Charles as

his guest. Before his lease expired, there being five years to run,

Lochiel and Clunes bargained for a new lease for 19 years from

Whitsunday 1815, at the enormous rise of treble the old rent, or

£300. A favourite plan of Lochiel's was to ask a grassum, and allow

for it in the rent, and here Clunes paid £r000 of grassum, getting

the actuarial value in the reduction of rent, while the years to run

of the old lease were also taken into account. Nothing but the

tenant's intense attachment to the home of his forefathers justified

such a rent, and when the place came to be re-set in 1834 to Allan

Cameron and his son Captain John, the rent had to be reduced to

£200. It may be said that none of the tenants was able to stand the

increased rents, and large and regular abatements had to be made

yearly. II. Moy.—The

old rent of the two Moys was £57 6s 8d, payable by 16 tenants. Allan

Cameron valued the place at £70. Hugh Robertson, Lochiel's factor,

became tenant, and in 1823 got a 19 years' lease at a rent of £120,

burdened also with rates of is per £ and half the expense of a

considerable fence with Erracht.

III. Annat.—The old rent was £22 ios,

and Allan Cameron's valuation, £60. In 1815 it is set to John

Kennedy of Kirkland for 19 years at a rent of £240, so enormous that

at the renewal of 1834 the place only fetched £150, and in 1853,

although Achdalew was conjoined to it, both places only fetched

£200, from Lieutenant-Colonel John Cameron, Lienassie.

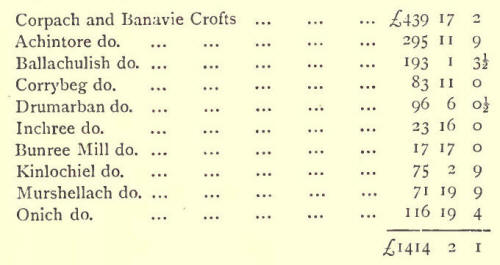

The total rental in 1788, shortly after

Donald Cameron's restoration, was £118 8s 6d1 while at his death in

1832 and for some time before it was not less than £6661 95 6d, not

a shilling of which was shooting rent.

Upon the accession of the late Donald

Cameron of Lochiel in 1832, the estate was in debt to the amount Of

£33,000, burdened at the same time with handsome family provisions,

and having a rack-rented tenantry, with a fluctuating surplus of

some £1600 a year.

The house of Achnacarry had not yet been

finished, and thus the younger Lochiel, though a frequent visitor to

Lochaber in his father's lifetime, and well acquainted with the

people, had no home in the North. His position was a most unhappy

one, having every wish to do what was right and proper to one in his

position, but possessing insufficient means.

Not a sixpence was left to the late

Lochiel from his father's executry, which included the considerable

unsettled claim against the Canal Commissioners, and all the woods

on the estate, but much to his credit he fought as it were against

fate, struggling to do justice to his tenants, even beyond his

means. When sheep farming was flourishing, the pinch was not so much

felt. South country tenants cropped up, and took the farms and

valuations. Later on, however, the demand fell off, and the question

of valuation began to be serious, even in the late Lochiel's time.

Landlords to a great extent are to blame for having in those days

winked at the pernicious valuation system, not in the beginning

affecting themselves directly.

It may be interesting to know who, out

of the whole Highlands, the late Lochiel singled out as the most

reliable valuators, and to be depended on, viz.—Thomas Gillespie of

Ardochy, and Coil Macdonell of Inch.

I have said that Mr Belford was not to

be blamed for the rise of the Lochiel rents and starving out of the

people, but he is to blame for another phase of sheep farming, viz.,

that of consolidating farms. To landlords, who by the sheep farming

system got rid of the people, it was further most advantageous to be

freed from the cost of buildings, fences, etc. Hence, even

shepherds' houses, fanks, fences, stells, etc., involved on every

farm a certain expense which might be greatly reduced by

consolidation.

CONSOLIDATION OF SHEEP FARMS.

This in time became serious, but I can

only give one illustration of how sheep farming grew, extending

within itself like a cancer. I do not blame those who, paying

enormous rents of necessity, strove to extend their borders and

curtail their outlay. "More land and no people" was their object and

cry. Alexander Macdonald, of Glencoe, and John Campbell, Younger of

Glenmore, were great monopolists on Lochiel, and other estates. Upon

their downfall a shrewd careful shepherd, known at first as "John

Cameron, drover, Corrychoillie," appears, afterwards becoming one of

the most noted men of his day. His first place on Lochiel was the

small farm of Coanich and Kenmore, which he entered in 1824 on a

]ease of ten years from Whitsunday 1824, the rent being

£70—superseding the old tenants, "Ewen Cameron and others." During

the currency of this lease Corrychoillie had added considerably to

his possessions, viz., Murligan and Caillich, part of Glenkingie and

Glen Pean ; while in 1834 his farms culminated in his obtaining a

lease of—1. Munquoich; 2. North Side of Glendessary, both as

possessed by the heirs of Alexander Cameron; 3. CrielI; 4. Salachan;

5. Muick; 6. Half or Kenmore, all as possessed by the heirs of

Lieutenant-Colonel John Cameron; 7. Murligan; S. Caillich; 9.

Grazings of Glenkingie; 10. Coanich; 11. West Kenmore, with the part

of Glenkingie attached to Coanich; 12. Glen Pean More; 13. Glen Pean

Beg; 14. Coull; and 15. Glaickfearn, all as possessed by

Corrychoillie himself. The rent, with is per £ for rates and taxes,

was £1430, on a lease of 19 years from Whitsunday, 1834, with a

break in favour of either party in 1845. Large as this rent was it

was not equal to the old rents exacted by the restored Lochiel,

which came to £1700; thus—Glendessary, £590; Glen Pean, £960; Crieff,

etc., £150—total, £1700. Lochiel himself did not expect this sum,

but would have been contented with £1490. Corrychoillie, whose

original offer was £1400, increased it to £1430, which offer, as he

would not move further, Lochiel accepted, and in doing so on the 6th

of January, 1834, wished the acceptance to be accompanied by these

words— "The

gratification I experience at the near prospect of having a tenant

of my own name, who by his activity and enterprise has been enabled

to hold of his landlord and chief farms of greater value and extent

than are in the possession of any one individual in the West

Highlands."

This good feeling did not last long, not even to the break in 1845,

and the cause of difference singularly was the well-known Ewen

Macphee, afterwards called the "Outlaw of Loch Quoich," regarding

whom so much was written and said fifty years ago. Macphee had been

resident on Glenkingie, by Loch Quoich side, and left undisturbed by

the previous tenants. Corrychoillie, a busy man, could not endure

idlers, particularly such as inclined to go about with a gun in

place of labouring or shepherding. The two met in a hostile manner

on several occasions, one of the encounters ending in a threat on

the part of Macphee to shoot Corrychoillie. Lochiel tried to

mediate, taking up a very proper and considerate position. Upon the

27th of March, 1835, he writes—

"Let me have a particular account of

Macphee's proceedings, his manner of life, and what his family

consist of. My feeling with regard to this man is that having been

so long unused to habits of industry or occupation of any kind, that

when turned adrift he may have recourse to lawless proceedings for

his support. Men of his stamp are sometimes reclaimed by kindness,

when severity might drive them to desperation. On this principle, if

I thought the man had any of the better principles of Rob Roy, I

would endeavour to provide for him myself. In the meantime there can

be no doubt that I am bound to clear the farm of him at the

insistence of the tenant."

Again, fifteen months later, on the 23rd

of March, 1835, Lochiel writes-

Corrychoillie made repeated complaints

to me of the conduct of Macphee, and of loss he has sustained by

him, both of which I cannot but think are somewhat exaggerated, as

were he really the desperate character represented, surely

AlexanderCarneron, Inverguseran, and Thomas Macdonald (former ten

)would neither of them have suffered him to remain on the farm. As

to the threat of shooting Corrychoillie, I think he is more likely

to do so if he and his family are turned adrift at his instance. I

should have thought that to a man of Corrychoillie's immense

possessions, an acre or two of potato ground would be unworthy of

consideration."