|

FROM the frequent mention of

linen in the history of Scotland, it is evident that the inhabitants were

acquainted with the processes of making cloth from flax six hundred years

ago at least. It is related that, at the battle of Bannockburn (fought in

the year 1314), "the carters, wainmen, lackeys, and women put on shirts,

smocks, and other white linens, aloft upon their usual garments, and bound

towels and napkins on their spears, staves, &c. Then placing themselves in

battle array, and making a great show, they came down the hillside in face

of the enemy with much noise and clamour. The English, supposing them to be

a reinforcement coming to the Scots, turned and fled." There is good reason

for concluding that the linen so successfully displayed on this memorable

occasion was home-made. At first the flax was grown, dressed, spun, and

woven by the people for their own use; but towards the close of the

sixteenth century linen goods formed the chief part of the exports from

Scotland to foreign countries. About the same time a considerable quantity

of Scotch linen found its way into England. Several attempts were made to

establish linen manufactories, so that the trade might be extended and

carried on more profitably; but the promoters, though encouraged by royal

favours and the concession of certain privileges, did not succeed. Efforts

were made to improve and extend the woollen manufactures of Scotland by

various legislative enactments, one of which prohibited the importation of

woollen – — cloths from England. The English people retaliated for this

interference with their trade by treating the men who sold Scotch linen in

their territory as malefactors, whipping them, and making them give bonds

that they would discontinue the traffic. This told seriously on the working

population of Scotland, for it was calculated that from 10,000 to 12,000

persons were employed in making linen goods for the English market. An

appeal to the king had the effect of removing the restrictions on the trade.

In 1686 the first Parliament of James VII. passed an "Act for Burying in

Scots Linen," the object of which was to encourage the linen manufacturers

in the kingdom, and prevent the exportation of the monies thereof by

importing linen. It was enacted that "hereafter no corpse of any persons

whatsoever shall be buried in any shirt, sheet, or anything else except in

plain linen, or cloth of hards, made and spun within the kingdom, without

lace or point." Heavy penalties were attached to breaches of the Act, and it

was made the duty of the parish minister to receive and record certificates

of the fact that all bodies were buried as directed.

It would appear that the

weavers, in order to increase their gains, had, towards the end of the

seventeenth century, begun to make linen cloth of inferior quality, and

Parliament interposed to put a stop to that practice. In 1693 an Act was

passed "anent the right making and measuring of linen cloth." It set forth

that "the King and Queen's Majesties considering how much the execution of

the good laws for the right making of linen cloth hath been hitherto

neglected, to the prejudice of the lieges, and the loss of trade within this

kingdom, do therefore, with advice and consent of the Estates of Parliament,

ratifie, approve, and confirm all Acts of Parliament made for the right

making and improving of linen cloth." The Act then proceeds to describe

minutely how yarn is to be made up and sold, and how the cloth is to be

woven and measured; and this in consideration of "how much the uniform

working and measuring of linen cloth may raise the value thereof with

natives and strangers, and render the trade more easy and acceptable to

merchants." In order to afford protection against dishonest work, the Act

required " that the owner of all linen cloth made for export, before it be

exposed to the first sale, shall be obliged to bring the same to a royal

burgh where linen is in use to be sold, there to receive the public seal and

stamp of the burgh, bearing the coat-of-arms of the burgh upon both the ends

of ilk piece or half piece thereof, which shall be a sufficient proof of the

just length and breadth, evenness of working, and the due and sufficient

thickness and closeness thereof; and for that effect there shall be in each

royal burgh where linen is in use to be sold, an honest man well seen in the

trade of linen cloth appointed to keep the said seal for marking linen

therewith." The fees to be charged by the stampmaster were also fixed by the

Act, and he was subject to penalties if he neglected his duty. For the

encouragement of all persons who should establish manufactories of linen

cloth it was further "statute and ordained, that all lint, flax, and linen

yarn imported for the use of companies or manufactories, and all linen cloth

exported by them, shall be free of custom duties or excise."

The linen manufacturers of

Scotland derived great advantage from the union with England. The duties

charged on goods exported to the sister kingdom were removed, and at the

same time the colonies were opened to Scottish enterprise. A period of great

industrial activity set in, and the quantity of linen goods produced was

much increased. In 1710 upwards of 1,500,000 yards of linen cloth were

produced. Ten years afterwards England alone took L.200,000 worth of Scotch

linen annually. A great stimulus was given to the trade by the establishment

of the Board of Manufactures in 1727. The fifteenth section of the Treaty of

Union with England, signed in July 1706, stipulated that "L.2000 per annum

for the space of seven years shall be applied towards encouraging and

promoting the manufacture of coarse wool within those shires which produce

the wool," and that " afterwards the same shall be wholly applied towards

the encouraging and promoting of the fisheries and such other manufactures

and improvements in Scotland as may most conduce to the general good of the

United Kingdom; and it is agreed that Her Majesty (Queen Anne) be empowered

to appoint committees who shall be accountable to the Parliament of Great

Britain for disposing the said sum." No action was taken to fulfil the

conditions of this clause of the Treaty until 1727, when an Act was passed

for the appointment of twenty-one commissioners to take charge of the

revenues and annuities allotted to the encouragement of manufactures and

fisheries. By that time the money which was to be devoted to the improvement

of the woollen manufactures had accumulated to the sum of L.14,000; while

L.6000 in addition was due for the other purposes referred to in the section

of the Treaty under notice. The interest on those sums, added to an annuity

of L.2000, placed a considerable amount at the disposal of the "Board of

Trustees for Manufactures," as the commissioners were designated, who laid

before the King in council a triennial plan for the apportionment of the

revenues.—The first plan prepared was for the three years from Christmas

1727, and provided for the expenditure of L.6000 yearly in the following

proportions :—For the herring fisheries, L.2650; for the linen trade,

L.2650; and for spinning and manufacturing coarse tarred wool, L.700. The

money allotted to the linen trade was divided as follows :—Premiums for

growing lint and heffip seed at 15s. per acre, L.1500; encouraging spinning

schools for teaching children to spin lint and hemp, L.150; prizes for

housewives who shall make the best piece of linen cloth, L.200; salaries to

the general riding officers at L.125 each, L.250; salaries to forty lappers

and stampmasters at L.10 each, L.400; expenses of prosecutions, L.100;

procuring models of the best looms and other instruments, L.50. It would

appear from this that technical education is not such a new thing in this

country as some persons suppose—the spinning schools referred to being

places in which a technical knowledge of a certain branch of industry was

imparted to young persons. The sum of L.10 a-year was allotted to the

endowment of each seminary, of which sum the teacher or mistress received

L.5 as salary; L.4, 1s. 8d. was devoted to the purchase of fourteen spinning

wheels, at 5s. 10d. each; 5s. to maintaining pirns, bands, &c.; and the

balance, 13s. 4d., went to provide coal and candles for the session, which

lasted from the 13th October to the 15th April. The spinning schools were

situated chiefly in the Highlands, as the trustees considered it highly

desirable to create habits of industry in those regions where indolence and

poverty reigned supreme.

The Board lost no time in

taking steps for improving the quality of the linen made in Scotland; and

their records show, that one of their first acts was to propose to Nicholas

d'Assaville, cambric weaver, of St Quentin, France, to bring over ten

experienced weavers of cambric, with their families, to settle in this

country, and teach their art to others. The offer was accepted, and the

Board purchased from the Governors of Heriot's Hospital five acres of ground

in Broughton Loan, a suburb of Edinburgh, on which they built houses for the

French weavers. The colony was named Little Picardy, and its site is now

occupied by Picardy Place, which, with York Place, forms the eastward

continuation of Queen Street. The Frenchmen were Protestants, and they began

operations in 1729—the men to teach weaving, and their wives and daughters

the spinning of cambric yarn. A man skilled in all the branches of the linen

trade was at the same time brought from Ireland, and appointed to travel

through the country and instruct the weavers, and others, in the best modes

of making cloth.

It may be interesting to note

a few facts contained in the minutes and annual reports of the Board. In

1728 premiums were offered to persons who should construct bleachfields.

Several persons offered to make fields; and it was agreed that they should

receive L.50 for each acre of ground so laid out. Considerable sums were

also paid for the introduction of improved modes or appliances for dressing

flax. A dispute arose at Irvine in 1732 as to the adjudication of the

housewives' prize for making linen cloth. On reference to the Board, the

prize was given to the wife of the minister of Dreghorn. At that time the

linen manufacture was reported to be in a flourishing condition, and it went

on steadily increasing till 1740. During that year the manufacture of coarse

linens met with a serious check from the severe frost which prevailed in the

winter season. The weavers were badly provided with houses, and were unable

to work during the frosty weather. That circumstance, coupled with the high

price of provisions, led to many of the men leaving their employment and

enlisting in the army. In 1745, L.50 was awarded to John Johnston for the

invention of an ingenious method of throwing the shuttle in broad looms. In

1750 premiums for sowing flax-seed were discontinued, owing to want of

funds. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1753 giving L3000 per annum for

nine years (in addition to the L.2000 formerly granted) to the trustees, to

be applied by them for encouraging and improving the manufacture of linen in

the Highlands. No part of the said sum was to be given for any other use

than instructing and inciting the inhabitants of that part of Scotland to

raise, prepare, and spin flax and hemp, and to weave the same into coarse

linens. This was regarded as a judicious act, calculated to wean the

turbulent Highlanders from their feudatory propensities, and to impart a

spirit of industry to them. With a view to the proper administration of the

fund, the surveyor of the Board made a tour of inspection to several

districts of the Highlands, and the report he wrote on the condition and

manners of the people excited much attention, as it revealed the existence

of a state of matters little removed from barbarism. In 1755 the Trustees

reported that the cambric manufacture established in Edinburgh by foreign

weavers had not succeeded, the prohibition against importing and wearing

French cambric having increased smuggling, and thrown great quantities of

French cambric into the country duty free. The Trustees opened a Linen Hall

in Edinburgh in 1766 for the reception and sale of goods; and for nearly

five and twenty years the hall served its purpose of accommodating the

trade. In 1790 a representation was made to the Board to the effect that the

manufacturers did not then consider the hall to be any advantage, and

therefore it was closed. There were 252 lint mills in Scotland in 1772,

distributed as follows:—Aberdeen, 7; Ayr, 22; Banff, 8; Caithness, 1;

Dumfries, 1; Dumbarton, 16; Edinburgh, 2; Elgin, 3; Fife, 11; Forfar, 31;

Haddington, 1; Kincardine, 2; Kinross, 5; Lanark, 31; Linlithgow, 4; Perth,

73; Renfrew, 3; Ross, 3; Stirling, 28. It was reported in 1773 that several

new kinds of manufacture had been introduced—such as the making of gauzes

and thread at Paisley; while the spinning of silk, wool, and cotton, had

been considerably extended. In 1787 a premium of L.100 was awarded to Mr

Patrick Taylor, Edinburgh, for introducing a mode of figuring linen

floorcloth. Many improvements in machinery, &c., are noted, and frequent

mention is made of the introduction of the modes or appliances used in other

countries. In 1790 a great step in advance was made by Messrs James Ivory &

Co., who erected at Brigton, Kinnettles, Forfarshire, a mill for spinning

yarn by machinery driven by water power. The trustees resolved to reward the

enterprise of the firm by awarding to them a premium of L.300; but, in

consequence of some matter affecting the patent, they subsequently withdrew

the award. In the same year the trustees purchased the vested rights of the

foreign weavers in Little Picardy. The weavers had found it necessary, on

account of the cambric trade not succeeding, to apply themselves to other

occupa¬tions. By the close of the century the spinning schools would appear

to have accomplished the purpose for which they had been originated, as in

the year 1800 the Board refused an application from Sir John Sinclair to

have spinning schools established in Caithness, the grounds of refusal being

that spinning was then so generally known and so easily acquired as to

render schools for teaching it no longer necessary. The awards of the Board

were not always made in the strict spirit of the constitution, as in 1802

they gave ten guineas to a man in Alyth " for his ingenuity and industry in

weaving with a wooden arm and hand." The premiums offered to the linen trade

in 1807 were for the best and second best ravens-duck, shirting, diaper,

huckaback, plain linen, &c. There were eleven prizes in all, and five of the

successful competitors belonged to East Wemyss, three to Dunfermline, two to

Edinburgh, and one to Culross. It was reported in 1821 that the crop of flax

had decreased very much, owing to the low price current. In 1822 the king

approved of L.15,000 being expended on building offices for the Trustees at

the north end of the Mound, Edinburgh. The building, now called the Royal

Institution, was completed in 1828, at a cost of L.20,424. The abolition in

1823 of the law relating to the stamping of linen in Scotland curtailed the

functions of the Trustees. The manufacturers had frequently urged the

injurious effect of the operations of the Board, and were ultimately

successful, as stated, in having all legislative interferences with the

trade abolished.

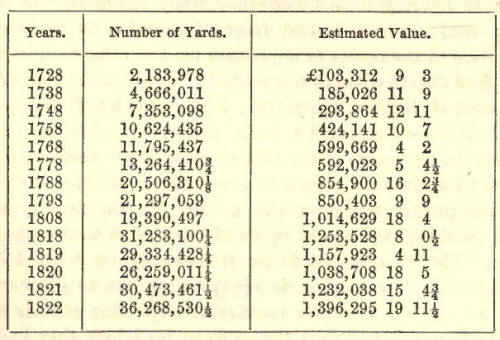

A record is preserved of the

quantity and value of linen cloth stamped in each year during which the

jurisdiction of the Board of Manufactures extended to the trade. The figures

relating to every tenth year up till 1818, as well as those for the last

four years in which the stamp-laws were in force, are subjoined:—

The above figures show the

development of the trade under the encouraging influences extended to it;

but the credit does not lie altogether with the Board of Manufactures. The

British Linen Company, incorporated at Edinburgh in 1746, did much good by

advancing money to the manufacturers, and helping them to dispose of their

goods. The company originated with the Duke of Argyll, and other noblemen

and gentlemen, who, finding that the linen manufacturers were frequently

placed in a position of difficulty by the fluctuations of the market for

their goods, and that sales had sometimes to be made under value in order to

raise money to meet pressing engagements, resolved to form a company for

trading in all branches of the manufacture. With a capital of L.100,000, the

subscribers of which were actuated solely by patriotic motives, the company

imported flax, linseed, and potashes, which they sold on credit to suitable

persons, afterwards buying at a fair price the yarns and linens made from

the material supplied in that way. The company had warehouses in Edinburgh

and London, in which they stored their purchases, and thence disposed of

them by exportation and otherwise. After a time, the company came to think

that they could best promote the branch of industry to which their attention

was specially devoted, by advancing money to manufacturers, and allowing

them to prosecute the trade on their own account, free from the competition

of an incorporated body. The company accordingly suspended operations as

dealers in linen, and adopted banking as their sole business. In the latter

connection the incorporation still exists, retaining its original

designation of "The British Linen Company."

For several years after the

repeal of the Act anent stamping linen, a system of inspection was in

operation; but it was entirely voluntary. The inspectors, in most cases,

were the same persons who had acted as stampers under the Act, and so were

generally well qualified for the work. Manufacturers either took their cloth

to the inspector, or, as was more commonly the case, got the inspector to go

to their factories. If the inspector was satisfied with the quality of the

cloth he stamped it with his own name. Such a system was liable to abuse,

however, and the stamps of the inspectors soon lost whatever value they had.

Merchants became better acquainted with the quality of the goods they

bought, and were content to deal according to their own judgment, without

the intervention of inspectors.

It would appear that linen

was an article available in making payments of rent in kind; for the rental

lists of the Marquis of Huntly show that in May 1600 the payments of that

description included 990 ells of linen. Dressing and spinning lint formed an

important part of the domestic duties of the wives of farmers and cottars in

those days. In an account of a tour in the Highlands of Scotland made by an

Englishman in 1618, it is stated that "the houses of the gentry are like

castles, and the master of the house's beaver is his blue bonnet; he will

wear no shirts but of the flax that grows on his own ground, or of his

wife's, daughters', or servants' spinning; his hose, stockings, and jerkins

are made of his own sheep's wool." Sixty years later another visitor

wrote:—"But that which employs great part of their land is hemp, of which

they have mighty burdens, and on which they bestow much care and pains to

dress and prepare it for making linen, the most noted and beneficial

manufacture of the kingdom." A third visitor, who came in 1725, wrote as

follows:—

"Many of the Scotch ladies

are good housewives, and many gentlemen of good estate are not ashamed to

wear the clothes of their wives and servants' spinning." Among some notes of

the manners and customs of the people of Scotland, written by a lady who was

born in 1714, is the following:—"Linens being everywhere made at home, the

spinning executed by the servants during the long winter evenings, and the

weaving by the village webster, there was a general abundance of napery and

underclothing. Every woman made her web and bleached it herself, and the

price never rose higher than 2s. a-yard, and with this cloth almost every

one was clothed. The young men, who were at this time growing more nice, got

theirs from Holland for shirts; but the old ones were satisfied with necks

and sleeves of the fine, which were put on loose above the country cloth.

Table linens were renewed every day in gentlemen's families, and table

napkins were always used. A few years after this, weavers were brought from

Holland, and manufactories for linen established in the west. Holland, being

about 6s. an ell, was worn only by men of refinement. I remember, in the

year '30 or '31, of a ball where it was agreed that the company should be

dressed in nothing but what was manufactured in the country. My sisters were

as well dressed as any, and their gowns were striped linen at 2s. 6d. per

yard. Their head-dresses and ruffles were of Paisley muslins, at 4s. 6d.,

with fourpenny edging from Hamilton—all of them the finest that could be

had. At this time hoops were constantly worn four and a half yards wide."

With reference to the linen trade, Mr Patrick Lindsay, in his book on the

"Interest of Scotland," already quoted, expresses himself strongly on the

"woeful neglect" with which it was treated at the time he wrote, in 1733;

and he makes suggestions for remedying a state of matters so undesirable.

The following extract contains some of his views:

"If all our spare and idle

hands were employed in the linen, and thereby enabled to live comfortably by

their own labour, and to bring in a little wealth to the country, the

improvement of our other manufactures might be safely left to themselves,

for it is more our interest to be served with several kinds of goods from

England, so long as they are bought cheaper in England and our linen sells

to advantage there, than to be overstocked in any branch of business which

we cannot export; and in this our greatest danger lies. Many of our young

joiners and other young tradesmen go now and then to the plantations for

want of suitable encouragement at home. Were all these supernumerary

tradesmen bred to be linen weavers, how much might this valuable manufacture

be increased, by employing in it so many more hands. As manufacture was in

no esteem, men of fortune thought it beneath them to breed their children to

any business of that sort; and, therefore, since war ceased to be our chief

trade, the professions of law, physic, the business of a foreign merchant

and shopkeeper, reckoned the only suitable employments for persons of birth

and fortune, have been greatly overstocked. Several young men, bred to no

business, pretend to turn merchants, and follow trade in the smuggling way,

and thereby do great hurt to the fair trader, and to their country, and in

the event ruin (for the most part) themselves. After the Revolution many

churches continued vacant for several years, and young men were no sooner

qualified for the ministry, than they were sure of a settlement; and even

too many were admitted (to the discredit of the profession) before they were

so well qualified for it as the dignity of the office requires. Our Church

livings are but small, and therefore few people of rank or any condition

educate their sons for clergymen; whereby these many vacancies were a great

temptation, and an encouragement to people of low rank to follow that

profession. One bad effect of this way of supplying vacant churches to the

public is, that as these clergymen have nothing but their stipends to depend

upon, unless they are frugal beyond measure, and parsimonious to a fault; if

they have wives and children, these must be left indigent, as burdens upon

the public. The case is now much altered as to vacancies, for at present we

are so overstocked with young clergymen, that one-half of the probationers

who are now candidates for the supplying of churches as they fall vacant can

never in reason hope to be provided for. The public suffers greatly under

this heavy burden of so many idle and useless hands; and of all professions,

an unemployed clergyman is the most helpless and useless member of society.

Thus it is evident that every profession, and every trade (except the linen)

is, and is very liable to be, overstocked in numbers; but the linen trade,

if duly improved, is sufficient to employ our supernumerary hands, and can

never be overstocked. The linen manufacture may be brought to as great an

extent in value as any other business now carried on in Britain, except the

woollen; and it may employ near as many hands as the woollen does. And the

linen trade of the north is of as great consequence to the nation in general

as the woollen in the south, and equally deserves the same care,

countenance, and encouragement from the public."

When the Board of Trustees

for Manufactures began operations in 1727, the manufacture of linen was

carried on in twenty-five counties of Scotland, the quantities produced in

each varying from 65 yards (valued at L.3, 7s.) in Wigtownshire, to 595,8212

yards (valued at L.13,989, 10s.) in Forfarshire. Perth, Fife, and Lanark

came next in order. Subsequently, linen was made in all the counties except

Peebles. Forfarshire kept the lead all through, and still occupies the

foremost place. In 1822—the last year in which the stamp-laws were in force,

and, consequently, the last respecting which any accurate statistics

exist—the chief seats of the trade and the quantities of linen stamped were

as follow:—Forfarshire, 22,629,5532 yards; Fifeshire, 7,923,3881 yards;

Aberdeenshire, 2,500,4031 yards; Perthshire, 1,605,321 yards;

Kincardineshire, 632,896 yards; Inverness-shire, 318,465 yards; Cromarty,

297,754 yards; Edinburgh, 129,709 yards. During the past thirty or forty

years, the manufacture of linen has died out in many towns and villages in

which it at one time formed the chief branch of industry, and has been drawn

together into the counties of Forfar, Fife, and Perth.

The following notes, drawn

chiefly from the "Statistical Account of Scotland," will show how the

manufacture was dispersed over the country seventy or eighty years ago; how

the people of some districts failed to take it up; and again how it grew and

flourished for many years in certain towns in which it is now unknown.

Beginning with the "far north," it is recorded that about the year 1790 an

attempt was made to introduce the linen manufacture into Shetland, but

without success. As the people could purchase linen cheaper than they could

make it, they did not take kindly to the new industry; and, besides, their

habits and constitutions would appear to have been ill-suited to the

vocation, for it is said that "the fair sex were so accustomed to roam about

the rocks, that they could not apply themselves with diligence to the

manufacturing business; and the constant sitting was said to have brought on

hysterical disorders." In Orkney the case was different. The making of linen

yarn from home-grown flax was introduced in 1747, and in course of time the

trade spread over nearly all the islands. The yarn made acquired a good name

in the southern markets, and from 1750 till 1785 about 250,000 spindles were

exported annually. After that time the trade gradually declined, and it was

abandoned about the close of the century. Weaving was introduced at the same

time as spinning, but it never attained much importance. The greatest

quantity stamped in any year was under 30,000 yards. The cloth was sold in

Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Newcastle, at an average price of eleven pence

a-yard. The chief cause of the decline of the trade was the low price paid

by the country agents for spinning and weaving. It is said that latterly the

most expert spinners could not earn more than twopence a-day. The

substitution of linen underclothing for home-made woollen shirts and vests

was alleged to have seriously affected the health of the people, colds and

rheumatism having become much more common among them. Before the sea fishing

received much attention from the inhabitants of Caithness, and before the

now famous pavement quarries of that county were opened up, the making of

linen cloth, and other domestic industries, were carried on by the people,

but chiefly to supply their own wants. The farmers grew small patches of

flax, which supplied the raw material, and in course of time quantities of

dressed flax were imported. At Thurso a large number of persons were

employed towards the end of last century in spinning flax for the

south-country merchants. The Custom-House books show that, in 1794 and the

two following years, 253,749 lb. of dressed flax were brought to Thurso,

which would produce 162,342 spindles of yarn. The spinners were paid at the

rate of is. and the agent 2d. a-spindle. From this it would appear that, in

the three years mentioned, the total sum paid for spinning, &c., was L.9294,

no inconsiderable amount to be set loose in those days in a poor district of

the country. In 1851 an attempt was made by Mr Peter Reid, proprietor of the

John o' Groat Journal, to revive the cultivation of flax in Caithness. Mr

Reid erected at Wick a mill for dressing flax by Schenck's process, and with

the aid of the Caithness Agricultural Society, got a number of farmers to

devote an acre or two of ground to raising flax He furnished the seed, paid

a rent for the ground, and gave prizes to those who produced the heaviest

crop per acre. At the time Mr Reid was induced to take up the trade,

agricultural affairs in Scotland were not in a prosperous state. Oats could

be purchased at 13s. per quarter, and oatmeal at 11s. per boll; and the

proposal to cultivate flax was hailed as likely to improve the prospects of

farmers. In Aberdeenshire, Fifeshire, and Lanarkshire, mills similar to Mr

Reid's were built, and inducements were offered to farmers to undertake the

cultivation of flax, and for a time it was thought that matters would turn

out advantageously for all concerned. The hopes which had been raised were

not realised, however, for in the course of a year or two the price of grain

rose, and the farmers re¬fused to have anything more to do with flax, which

they considered a troublesome crop, and not so remunerative as they had

expected. The failure of the enterprise was a sad blow to the mill-owners,

and in Caithness especially was the subject of much regret, for in that

county there is a scarcity of occupation during greater part of the year,

and the flax mill was expected to relieve in some measure the overstocked

labour market. During the few years that Mr Reid's mill was in operation,

the flax scutched at it fetched from L.50 to L.60 a-ton, a higher price than

was obtained for flax prepared at mills situated in more favourable

localities. About the close of the eighteenth century the spinning of linen

yam from flax imported from the Baltic was carried on in Sutherlandshire,

but on a very small scale. Some linen cloth was also woven for home use, and

occasionally, when the supply exceeded the demand, a few hundred yards were

stamped for sale. In Ross-shire flax and hemp were at one time cultivated.

The flax was dressed, spun, and woven to an extent which sufficed for local

requirements, and about L.500 worth of cloth was exported annually. The hemp

was converted into canvas and cordage for the fishing boats of Avoch and the

neighbourhood. Though the trade is now extinct in Cromarty, as well as in

the counties mentioned above, it would appear from the stampmaster's returns

that the inhabitants were at one time pretty extensively engaged in making

linen goods. In 1758 about 7950 yards were stamped; but during the thirty

years following there was a con-siderable falling off, followed, however, by

a somewhat sudden and extensive revival. Thus, while the number of yards

stamped in 1788 was 4656i, valued at L.186, 8s., in 1822 the figures were—

yards stamped, 297,754; value, L.13,461, 17s. At Inverness—a town which

possesses great natural facilities for carrying on manufactures, though

these have been very little taken advantage of—a large hemp factory was

established in 1765, and for some time was so prosperous as to employ 1000

hands. The hemp was brought from the Baltic, and was chiefly converted into

sacking and tarpauling cloth, a considerable portion of which was sent to

the West Indies to be used in covering bales of cotton. The factory is still

in existence, though the business done is not so extensive as it once was.

About the year 1780 an enterprising company began the manufacture of linen

thread, and for a number of years remarkable success rewarded their efforts.

They gave employment to 10,000 persons throughout the county, most of whom

worked in their own homes, their labours being superintended by district

agents, of whom there were nineteen. The earnings ranged from is. to 12s.

a-week. The flax was obtained from the Baltic ports; and when the thread was

finished, it was forwarded to London, and thence dispersed over 'the world.

The trade was taken up in some other towns, the social and commercial

circumstances of which were more favourable to its prosecution; and many

years ago, Inverness retired from competition with them. In the first year

following the passing of the Stamp Act, 10,696 yards of linen were stamped

for sale in Inverness-shire, and the quantity made increased gradually,

until in 1822 it reached 318,465 yards. From that time the trade declined

steadily, until it left the county altogether. Nairnshire also figured in

the stampers' returns, but to a limited extent, and for a brief period. In

the parishes of Elgin and Forres, in Morayshire, flax was grown at a very

early date, and in the former it appears that teind was paid on lint in the

twelfth century. About 1790 a large number of persons were engaged in

spinning flax for the southern markets, and about 50,000 yards of linen

cloth were produced annually. A like quantity of cloth was made in

Banffshire; but, in addition, nearly 5000 persons were employed in the

parish of Banff in making linen thread, in which about 3500 bales of Dutch

flax were used every year, and the value of the manufactured article was

L.30,000. The thread was sold in Nottingham and Leicester, where it was used

in making lace, &c. Competition in various quarters spoiled the trade, and

the people took to other kinds of work. In 1748 the Earl of Findlater

introduced the linen manufacture into the parish of Cullen. At that time the

Earl was President of the Board of Manufactures, and the mode in which he

carried out his object is thus recorded:—"The Earl took to Cullen two or

three young men, sons of gentlemen in Edinburgh, who had been regularly bred

to the business, and who had some patrimony of their own. To encourage them

to settle so far north, he gave them L.600 for seven years, the money to be

then repaid by yearly instalments, free of interest during the whole period

of the loan. He also built weaving shops and furnished every accommodation

at reasonable rates. From his position at the Linen Board, he obtained for

the young manufacturers premiums of looms, heckles, reels, and

spinning-wheels, with a small salary for a spinning-mistress. So good a

scheme and so great encouragement could not fail of success, and in a few

years the manufacture was established to the extent desired. All the young

people were engaged in the business, and even the old found employment in

various ways in the manufacture, which prospered for half a century." But

Cullen could not escape the influences at work in other quarters, and the

trade drooped and became extinct in the early years of this century. The

parishes of Keith and Fordyce shared in the prosperity which attended the

linen trade, but were as unable to retain it as their neighbours.

The next district to be noticed is that in which the trade has survived to

some extent the circumstances which led to its extinction in the counties

farther north. Aberdeenshire was early engaged in the manufacture of linen

yarn and cloth. About the year 1745 the Board of Manufactures sent a

spinning-mistress to Aberdeen, at the request of some persons who desired to

provide employment for the working population. Pupils were readily found

among the wives and daughters of mechanics and labourers, who soon turned

out yarn at the rate of 100,000 spindles a-year, for which they were paid in

the aggregate about L.5000. The manufacture of white and coloured linen

thread was subsequently begun, and was carried to great perfection. In 1795

the thread manufacture employed 600 men, who earned from 5s. to 12s. a-week;

2000 women, 5s. to Gs.; and 1.00 boys, .1s. 8d. to 2s. 6d. At the same time

upwards of 10,000 women were employed in other parts of the county in

spinning yarn for making the thread. Several large manufactories for

spinning flax by machinery were established on the Don, near Old Aberdeen,

about seventy years ago, and for many years the trade continued in a

flourishing condition. At Huntly the trades of dressing flax and making

linen cloth were carried on for many years, during the best of which the

value of the goods produced was about L.25,000 annually. Peterhead did

considerable business in the manufacture of thread. In 1794 there were

fifty-two twist mills in the town, at which the yarn spun by women in their

own homes was made into thread. About 1200 persons were employed in the

various departments of the manufacture. Linen yarn and cloth were made in

several other parts of Aberdeenshire The quantity of linen cloth stamped in

the county in 1758 was 103,109 yards. The quantity in any year prior to

.1790 did not rise much above these figures; but subsequently a great

advance was made, and the quantity stamped in 1822 was 2,500,403 yards.

Kincardineshire claims to be the first county in Scotland in which

flax-spinning by machinery was established. In 1787 a mill for spinning

linen yarn was erected on the Haughs of Bervie by Messrs Sim & Thom, who

obtained a license to do so from the inventors of the machinery at

Darlington. The mill is still in operation, but the original machinery has

given place to more modern contrivances. At Benholm and Auchinblae, in the

same county, the linen manufacture still survives, but on a much smaller

scale than formerly. 632,896 yards of linen were stamped in the county in

1822.

The early history of the

linen trade in the counties of Forfar, Fife, and Perth, in which that branch

of industry is now almost entirely concentrated, will be dealt with when the

present condition of the linen manufactures of the country comes to be

noticed.

The average quantity of linen

cloth made in Kinross-shire, from — 1780 till 1790, was 118,434 yards, worth

about L.4500. This does not include what was made for home consumption.

Between 300 and 400 looms were employed in the trade. The yarn was spun by

women, chiefly from flax raised in the county. In 1811 a period of

depression of trade was experienced throughout the country; and the

gentlemen of Kinross-shire, with the view of ameliorating the condition of

the working population, subscribed L.4000, and began to purchase on their

own account and risk, cotton and linen yarn,. which they gave out to weavers

to be made into cloth. The result did not come up to the expectations that

had been formed of the scheme, as the market was overstocked, and the goods

could be got rid of only at a losing price. The trade was then abandoned,

and has not been tried again. In 1756 the weavers of Kinross formed a trade

union, the members of which made themselves subject to stringent laws as to

work and recreation. In order to induce all in the trade to become members,

it was enacted that "none of the weavers already incorporated, or that may

hereafter be incorporated, shall, without the consent of the whole or

greater part of the subscribers, have any correspondence with

non-subscribing weavers in the way of borrowing or lending any of the

utensils of their craft, under pain of incurring such penalties as the

incorporated members shall inflict." Small annual payments were made by the

members, and breaches of the rules were punished by the infliction of heavy

fines. It was usual, on occasions of public rejoicings or fairs, for the

president of the society to issue an order enjoining the members to conduct

themselves with decorum and sobriety, and to go to their homes at an early

hour, under pain of dismissal from the society. The co-operative principle

was adopted by the members for maintaining the funds of their union. The

records of the society show that sums were advanced to members for the

purchase of yarn, which, when made into cloth, was sold; and whatever profit

remained after the cost of the yarn and the labour of the weaver were paid,

was returned to the treasurer of the society. The linen trade was several

times started in Clackmannanshire, but it does not appear to have attained a

sound footing at any period. About the year 1748 the Duke of Argyll

introduced the manufacture at Inverary, but it prospered only for a short

time. The people. of Buteshire also gave it a trial, but without success. In

Stirling- shire, from 30,000 to 40,000 yards of linen were made annually

about the beginning of this century, but for many years past no one in the

county has engaged in the manufacture. Dumbartonshire produced 310,827 yards

of linen cloth in 1758, but after that year the trade declined, until, in

1822, only 11,331 yards were made; and the industry is now extinct. A small

quantity of linen was produced in Linlithgow. Mid-Lothian long stood high in

the trade, which was chiefly concentrated in Edinburgh, as many as 1500

looms being employed on linens in the city. The manufacturers were famous

for making the finest damask table-linen, and linen in the Dutch manner

equal to any that came from Holland. So early as 1698 there is mention of a

bleachwork having been established at Corstorphine. The following figures

show the quantity and value of the linen cloth stamped in the county in the

years named :-1728-747 yards, valued at L.198, 17s.; 1738-18,988 yards,

L.2986, lls. 9d.; 1748-236,954 yards, L.9616, 18s. 10d.; 1758-712,719 yards,

L.36,132, 16s. 10d.; 1768-389,962 yards, L.32,191, 17s. 6d.; 1778-178,290

yards, L.22,674, 16s. 2d.; 1788-244,710 yards, L.36,338, is. 2d.;

1822-129,709 yards, L.22,287, 18s. The price of the cloth made in Edinburgh

was always high on account of the fineness of the quality. While the average

price over Scot¬land was about 10d. a-yard, the price of the Edinburgh linen

ranged from 2s. 6d. to 2s. 11d. The manufacture of linen goods has long

ceased to rank among the industries of the city. Salton, in Haddingtonshire,

is noted as having been the first place in Britain in which weaving of the

linen cloth known as "hollands" was established, and the first in which a

bleachfield of the British Linen Company was formed. In the beginning of

last century the lady of Fletcher of Salton, animated by a desire to

increase the manufactures of the country, travelled in Holland with two

expert mechanics in the habit of lackeys. Her rank procured her access, with

her supposed servants, to the manufactories; and by frequent visits, the

secrets of operations were discovered, and models of the various works were

made by the disguised artisans. The parish in that way became acquainted

with two valuable processes of manufacturing— the making of pot barley, and

the weaving of "hollands;" and for several years it supplied the whole of

Scotland with those articles. In Lanarkshire linen was manufactured on an

extensive scale at Glasgow and East and West Monkland. The trade was

established at Glasgow in 1725, and for a long period formed the staple

industry of the city. Nearly 3000 looms were in 1780 employed in linen

fabrics in the Barony parish alone. Ten years later, however, cotton had

almost entirely superseded flax, and the weavers were mostly occupied in

making muslin. At present about a dozen firms are engaged in the manufacture

of flax. In 1728 upwards of 272,000 yards of linen were stamped in

Lanarkshire; twenty years later the quantity was 1,191,982 yards; in 1768 it

was 1,994,906 yards; but in 1822 only 228,692 yards were submitted to the

stampmaster. The cotton trade had become the staple of the west, and linen

was neglected. Large quantities of linen cloth were made in Renfrewshire.

The highest figures are those for the year 1778, when 1,467,935 yards were

stamped in the county—being chiefly made in Paisley, where also a large

number of persons were engaged in making white sewing thread. The art of

making this thread was introduced into the neighbourhood from Holland in

1725, and was carried on for a long time in the family of a lady, who first

learned the secret and began the trade. The linen manufacture of Paisley

gave way before the introduction of cotton, and was long ago aban¬doned. Ayr

shared in the profits of the linen trade in its early days, but many years

since the people took to other pursuits. Kirkcudbright and Wigtown made a

small show in the returns, and Roxburgh and Berwick produced from 30,000 to

60,000 yards annually. Melrose was famous for its "land linens" from an

early date, and the weavers received many orders from London and the

Continent; but the trade began to decline about the year 1770, and never

rallied. Linen was a commodity in:which a great business was done at St

Boswell's fair, held in the parish of that name; but for a number of years

past none has been offered, as the trade has died out in the district.

Of 197 flax, hemp, and jute

factories ascertained to be in existence in Scotland in September 1867, 176

were situated in the counties of Forfar, Fife, and Perth. This concentration

of the trade has, as already shown, taken place in comparatively recent

years, and the causes of it are not difficult to discover. The human hand,

aided only by the rude appliances of ancient times, can ill compete with

modern machinery propelled by steam; and manufacturers in places where

circumstances were adverse to the introduction of the tireless agent,

naturally found it impossible to succeed in a competition with people more

advantageously situated. Hence the spinners and weavers of linen in the

outlying districts had to relinquish their wheels and looms, and follow the

trade to the absorbing centres, or seek new kinds of employment. The change

caused much hardship, and broke up many homes. Not a few of the weavers had

been able, in the more prosperous days of the trade in the rural districts,

to acquire little freeholds, on which they lived with their families in the

midst of happiness and contentment; and it was a sad day when the failing of

occupation compelled the sons and daughters to leave the parental roof and

go, it might be, many miles away to find a market for their labour. In the

long run, the change has been advantageous to a much greater number of

persons than those who suffered by it, and now its effects are almost

entirely obliterated, if not forgotten.

The linen and jute

manufactures are almost the only branches or Scotch industry dealt with in

this book which have previously had their histories written. A few years ago

Mr Alexander J. Warden, merchant, Dundee, published under the title of "The

Linen Trade, Ancient and Modern," an exhaustive and thoroughly trustworthy

treatise on every department of the manufactures referred to, and from a

second edition of the work, issued in 1868, some valuable information here

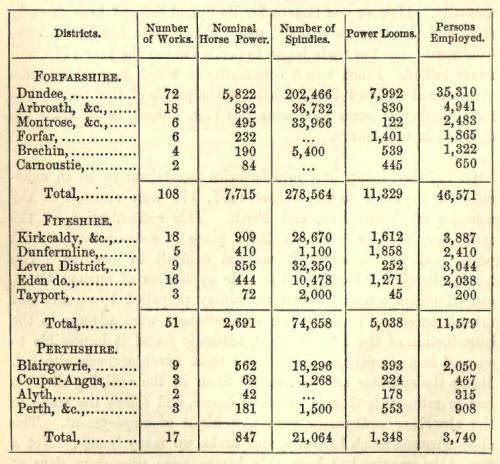

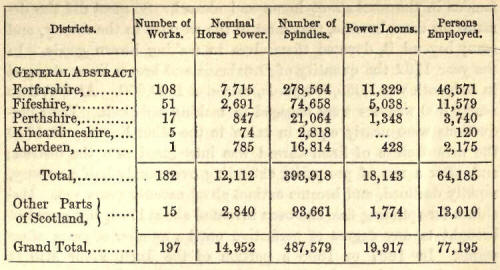

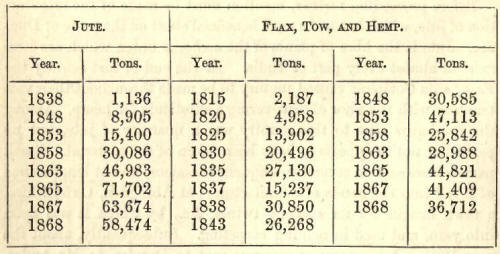

embodied has been drawn. Mr Warden gives the following statistics relating

to the flax, jute, and hemp factories of Scotland, as existing in September

1867

It will be seen from the

above figures that Forfarshire has considerably more than half of the entire

linen trade of Scotland. Putting Dundee aside for more special notice

afterwards, _Arbroath claims first attention. Though the conversion of flax

into cloth was practised on the banks of the Brothock for a number of years

previously, it was not until about 1738 that the trade began to assume

importance. The first impulse to the manufacture arose from one of the

Arbroath weavers accidentally discovering the mode of making the variety of

linen cloth called "Osnaburg," after the place in Germany where it was first

made and from which it was imported. The man had worked up a quantity of

flax which was unsuited for the kind of cloth then in demand in the home

market, and on taking his web to a merchant offered to give him a bargain of

it. The merchant recognised the similarity between the web the weaver was

disposed to look upon as almost unsaleable and the Osnaburg cloth; and not

only purchased the piece, but gave an order for some similar webs. The

weaver reluctantly accepted the order, little dreaming what a fortunate

discovery he had made. Before many months had elapsed, a large number of

weavers in the town and neighbourhood were engaged in the production of

Osnaburgs; and thus was laid the foundation of the almost uninterrupted

prosperity which the linen manufactures of Arbroath have enjoyed. Soon after

the discovery was made, a number of gentlemen of property in the town formed

themselves into a company for the manufacture of Osnaburgs and other brown

linens. They obtained the best machinery that was then known in the trade;

and, by devoting great care to the manufacture, succeeded in producing a

better quality of goods of the kind than was made elsewhere, and the brown

linens of Arbroath became famous in the markets at home and abroad. So great

did the demand for them become, that most of the weavers in the county, and

many beyond it, devoted themselves to making brown goods. In the year 1792

the quantity of Osnaburgs and brown linen stamped in Arbroath was 1,055,303

yards, valued at L.39,660. At that time nearly 500 weavers were engaged in

making sail-cloth. Their productions were nearly equal in value to the other

linens. In 1740 the manufacture of linen thread was introduced into the

district; and, after a run of prosperity extending over nearly half a

century, rapidly declined, and became extinct about seventy years ago.

Machines for spinning flax had been invented about 1790, but were not

brought to any degree of perfection until a number of years afterwards. In

1807 or 1808 a portion of the Inch Flour Mill at Arbroath was devoted to

giving the spinning machinery a careful trial. The efficiency of the

machines having been established, the flour grinding gear was cleared out,

and the entire mill devoted to flax-spinning. Subsequently additions were

made, and the mill is still in operation. The experiments at the Inch Mill

were watched with much interest; and when their entire success was

demonstrated, a change came over the trade, and the erection of factories

was proceeded with rapidly. A period of extraordinary prosperity set in

about 1820, and continued for five years. What followed is thus recorded by

Mr Warden:—" During this halcyon era were erected many spinning and other

works of an extent greatly beyond the means of the proprietors, and very

much beyond the legitimate requirements of the trade. There was then a

plethora of banks in the town, and in their competition for business

unwarrantable facilities were afforded to men without capital, and many of

them without experience or judgment. The natural consequence followed when,

in the beginning of the year 1826 (a year memorable in the annals of the

trade for the dire calamity which then burst upon the commercial world), the

manufactures of the place were all but unsaleable, money became scarce,

credit failed, and almost the whole manufacturing community, adventurer and

honourable merchant alike, were engulphed in one common ruin. Almost every

mill and factory was silent, distress prevailed throughout the town, and it

was some time before Arbroath became its former self again." In 1832 there

were sixteen spinning mills in Arbroath and its immediate neighbourhood; but

these were not so extensive as those at present in operation. The rates of

wages then current were:—Men from 10s. to 15s. a-week; women, 4s. 6d. to 5s.

3d.; boys and girls, 3s. 3d. to 3s. 6d. Ten years later the quantity of flax

spun annually in Arbroath was about 7000 tons, and the value of the yarn,

L.300,000. There were then employed 732 linen weavers, of whom a third were

women, and 450 canvas weavers, of whom about a fifth were women. In 1851

eighteen firms were engaged in the staple trade of the town. The horse power

of their engines was 530; the number of spindles, 30,342; power-looms, 806;

persons employed, 4620. These figures show, by comparison with the preceding

table, that during the seventeen years ending with 1867, the trade had not

increased much. It has, however, been maintained in a healthy state, and the

quantity of canvas made in Arbroath annually is about 500,000 pieces.

In the early years of last

century an annual market for linen yarn was held at Montrose, and thither

manufacturers from the adjoining counties repaired to dispose of their

goods. The making of sail-cloth was the first manufacture of any consequence

established in the town. It was begun in 1745 by a company, whose success

induced others to embark in the trade. The result was that it was overdone,

and canvas-weaving became almost extinct. Pennant states that, when he

visited the town in 1776, considerable business was being done in the

manufacture of sail-cloth, fine linen, lawns, and cambric. He adds that "

the men pride themselves in the beauty of their linen, both wearing and

household, and with great reason, as it is the effect of the skill and

industry of their spouses, who fully emulate the character of the good wife

so admirably described by the wisest man " The flax manufacturers of the

district readily adopted the machinery which had been invented for spinning,

and the first factory was built in 1805. In 1834 there were four large

factories in the town, all of which were worked by steam power. Besides

these, there were three factories on the North Esk, owned by Montrose firms,

and propelled by water. The aggregate spinning power was equal to the

production of 1,157,093 spindles of yarn annually. Some of the yarn was

woven in the town and district, but the greater part was sold to

manufacturers in other towns, or exported. The quantity of canvas and other

fabrics made in the town and neighbourhood was then about 50,000 pieces.

Though the factories have not increased in number since 1834, the productive

power of all has been extended. About 50,000 tons of flax, tow, &c., are

used annually. In addition to the persons engaged in the factories, a large

number of hand-loom weavers are employed. The chief characteristic of the

trade in Montrose is its steadiness, resulting from the caution of the

manufacturers.

When the people of Forfar

took up the linen trade, they de-voted their chief attention to weaving, and

to that they have adhered throughout, obtaining their yarns from other towns

which, like Montrose, are for the most part engaged in spinning. In 1792 the

linen weaving trade was in a flourishing state in Forfar. The principal kind

of cloth made was Osnaburg, and from 15s. to 20s. were paid for weaving a

piece of 120 yards in length, which occupied a man eight or ten days,

according to his ability and industry. In the early years of this century

the quantity of linen stamped in Forfar annually was about 1,800,000 yards;

and from 1816 till the abolition of the stamp laws in 1822, it was over

2,600,000 yards. Five and twenty years ago 3000 hand-loom weavers were

engaged in weaving coarse linens, of which about 2000 pieces were produced

weekly; and the value of the yearly produce would not be less than

L.250,000. Since that time the trade has increased considerably. The

manufacturers, having found that they could not compete successfully in the

markets unless they followed the example of other places and adopted the

power-loom, have introduced that machine; and the hand-looms, of which

nearly 5000 were in use a few years ago, are being gradually discarded.

Upwards of L.100,000 is spent annually in wages among the linen workers of

the Forfar district. The linens made are chiefly of the brown kind; and the

manufacturers have long been celebrated for the uniform and sterling quality

of their goods.

In the parish of Brechin flax

was cultivated at an early date; and after the manufacture of Osnaburgs was

established in the country, the people paid increased attention to the

cultivation of the fibre, and also to working it up into cloth. The quantity

of linen stamped at Brechin in the beginning of last century was upwards of

500,000 yards a-year, and in 1818 it reached 750,000 yards. The number of

persons employed in the trade at present is less than it was thirty years

ago; but the production is much greater, owing to the extensive introduction

of improved machinery. The premises of the East Mill Company are very

extensive. Though the original building was considered to be a large concern

in its day, its bulk is insignificant in comparison with the additions that

have from time to time been made. Up till a few years ago all the weaving in

Brechin was done by hand, but now there are three power-loom factories in

operation. There are two extensive bleach-fields in the town, capable of

bleaching about 4000 tons of yarn a-year. The principal fabrics made are

bleached shirtings, dowlas, and similar goods.

Eirriemuir, another

Forfarshire town which has retained its connection with the linen trade

through all its changes, is in the singular position of doing a large and

prosperous weaving trade by means of the hand-loom alone. In 1805, and the

two years following, the quantity of linen stamped in Kirriemuir averaged

2,226,200 yards a-year. In 1833 it was calculated that the rate of

production had increased to 6,760,000 yards annually; and at present it

cannot be less than 9,000,000 yards. About 4000 persons are employed, of

whom more than one-half are weavers. The manufacturers are disposed to erect

power-loom factories; but hitherto they have been unable to obtain suitable

sites. In the local history of the town, the name of David Sands, a weaver

of extraordinary ingenuity, who lived about the year 1760, is mentioned. He

invented a mode of weaving double cloth for the use of staymakers, and

subsequently succeeded in weaving and finishing in the loom three shirts

without seam. One of these he sent to the king, one to the Duke of Athole,

and the third to the Board of Manufactures.

In various other quarters in

Forfarshire, spinning, bleaching, and weaving linen are carried on, but

chiefly for manufacturers in the towns mentioned above.

The history of the linen

trade in Perthshire differs little from what has been recorded respecting

other counties. Blairgowrie is the chief seat of the manufacture—nine of the

seventeen firms in the county having their works on the banks of the Ericht

at that place. In the end of last century the linen trade was carried on in

no fewer than twenty-seven parishes of the county. 477,743 yards of linen

cloth were stamped in Perthshire in 1728; 793,228 yards in 1758; 2,651,674

yards in 1778; and 1,605,321 in 1822, the last year in which the stamp-laws

were in force. In the New Statistical Account of Scotland a curious remark,

emanating from this county, is made respecting the effect of spinning mills

on a rural population. The reporter from Caputh (writing so recently as 1839

be it remembered) says:—"Happily for the peace and purity of our quiet rural

population, no spinning mills have yet been erected, neither is any great

public work going on at present in this parish."

The figures relating to

Fifeshire show that, while the number of factories in that county is close

upon half the number in Forfarshire, the persons employed show a marked

difference in proportion, indicating that the factories of Forfar are, on

the average, more extensive than those of Fife. It will also be observed

that, in proportion to the spinning power, the number of power-looms at work

in Fife is greater than in Forfar—the number of spindles to each loom in the

former being about fifteen, while in the latter it is nearly twenty-five.

Kirkcaldy is the chief seat of the trade in Fife, and possesses some fine

mills. Though the art of making linen was known and practised in the

district about 200 years ago, the quantity produced was insignificant until

about 1743, when upwards of 300,000 yards were stamped in the town annually.

Kirkcaldy did not make the whole, however, as the figures include the cloth

brought in from Abbots- hall, Dysart, Leslie, &c., to be stamped. An annual

market for the sale of linen cloth was established in 1739, and various

other steps were taken by the magistrates to extend the trade.

Handkerchiefs, checks, and coarse ticks were the kinds of goods first made;

but the market for these having been spoiled by the war of 1755, which

interrupted communication with America and the West Indies, trade became so

bad that nearly all the looms were standing idle, and the manufacturers were

considering how to employ their capital more profitably. Before abandoning

the linen trade, however, Mr James Fergus resolved to try to produce

something that would sell in the home market. He studied the making of

"ticking," and succeeded in producing a fabric of first-rate quality. This

new branch of the trade was readily adopted by the desponding manufacturers,

and since then ticking has been one of the principal articles made in the

town. Towards the close of last century it was calculated that up-wards of

1,000,000 yards of linen, worth about L.50,000, were made annually in

Kirkcaldy. In 1818 the quantity stamped in the town (including the produce

of the neighbouring towns and villages) was over 2,000,000 yards. About

one-seventh of the linen made was from home-grown flax, the remainder being

made from flax imported chiefly from Riga. In 1793 three flax-spinning mills

were erected at Kinghorn, and two large spinning mills belonging to a

Kirkcaldy firm have long been in operation in that town. The number of

persons employed in the linen manufacture in Kirkcaldy about seventy years

ago was nearly 5000, and their average earnings did not exceed L.7 a-year.

The next statement of wages applies to the year 1838, when the net weekly

earnings of linen weavers averaged 7s. 3d. for ticks; 5s. 11d. for fine

sheeting; 3s. to 6s. 6d. for dowlas; and 9s. 3d. for sail-cloth. In the year

1821 a power- loom factory was built in the town, and is supposed to have

been the first establishment of the kind. The late Mr James Aytoun, of

Kirkcaldy, made some important improvements in the machinery used for

spinning flax, and adapted it to the production of yarn from tow. During the

past six or seven years the trade of the district, which had remained almost

stationary for twenty years, has been considerably extended, the additions

made to the spindles and looms being equal to nearly 100 per cent. There is

an extensive linen factory at Dysart, owned by Messrs James Normand & Son.

At Leslie several extensive

mills, beautifully situated on the banks of the Leven, give employment to a

large number of persons. These mills are owned chiefly by Messrs John Fergus

& Co. and Messrs D. Dewar, Son, & Sons, of London. Power-loom factories have

recently been erected at Tayport, Auchtermuchty, Falkland, Kings- kettle,

Ladybank, Strathmiglo, and elsewhere in Fife, all indicating that the trade

of the county is in a healthy state.

Dunfermline is the chief seat

of the manufacture of table linen. in Britain—indeed, it may be said, in the

world. When the linen trade was established throughout Scotland in the

beginning of last century, the people of Dunfermline shared in its profits,

and always aimed at the production of a high class of goods. They were most

successful in making table linen, and to that branch they have mainly

adhered. Long ago they had outstripped all competitors in their staple

industry, and the produce of their looms has for many years graced the

tables of royalty at home and abroad. At the Exhibitions of 1851 and 1862,

the goods shown by Dunfermline manufacturers attracted much attention, and

helped to extend their fame.

In the early days of the

linen manufacture only coarse goods were made in Dunfermline—first the

variety known as "huckaback," and subsequently "diapers." The weavers appear

to have been rather fond of trying the more difficult kinds of work, and

some of them adapted their looms to producing novel patterns of cloth. Great

ingenuity was also expended in weaving articles of dress without a seam. In

1702 a weaver in the town made a seamless shirt in the loom, and a like feat

was afterwards successfully accomplished by others. Two of those novel

productions are worthy of mention. In 1821 Mr David Anderson completed in

the loom a gentleman's shirt elaborately ornamented. It was of very fine

linen, and bore on the breast the British arms, worked in heraldic colours

and gold. For the accomplishment of the work he received L.10 from a fund

which had been formed in Glasgow for the encouragement of inventions and

improvements in manufacturing. The shirt was presented to His Majesty George

IV., who was graciously pleased to accept it, and to order L.50 to be sent

to the maker. Mr Anderson subsequently wove a chemise for Her Majesty Queen

Victoria. It was composed of Chinese tram silk and net-warp yarn, and had no

seams. The breast bore a portrait of Her Majesty, with the dates of her

birth, ascension, and coronation, underneath which were the British arms and

a garland of national flowers. The flag of the Weavers' Incorporation is

also a remarkable piece of work. It consists of a solid body of silk damask,

bearing a different design on each side, and yet both are interwoven.

Damask weaving was introduced

into the town in 1718, and the story of its introduction is somewhat

curious. Mr James Blake, a man of ingenuity and enterprise, went from

Dunfermline to Drumsheugh, near Edinburgh, where damask weaving was carried

on. The process of weaving was kept a close secret; but Blake was determined

not to be frustrated in his mission, which was to find out the secret and

work it for his own advantage. Feigning to be of weak intellect, he lounged

about the workshop in which the damask looms were employed, and ultimately

ventured in. The expression on his countenance when he saw the looms was so

full of puzzled wonder that the weavers allowed him to gratify his curiosity

by minutely examining the machines. He asked to be allowed to creep under

one of them that he might more closely watch its mysterious working. This

odd fancy of an idiot, as the workmen believed him to be, caused some

amusement; but no one objected to him going under the loom. While the

weavers were smiling at his bewildered stare, Blake was carefully noting in

his mind the manner in which the mechanism was arranged and how it operated.

He appeared to be fascinated by the looms, and was in no haste to go away.

When he did leave, however, he was in full possession of the secret.

Returning to Dunfermline, he at once began to construct a loom from memory,

and soon had the gratification of possessing a perfect machine. He had a

workshop in the old tower of the Abbey, and there, in company with one or

two faithful assistants, he devoted his whole time to making damask goods,

keeping well the secret which he had become possessed of in such a singular

way. It would appear that he was more successful in maintaining the secret

than the weavers of Drumsheugh, for his loom was the only one of the kind in

the town for many years. After the principle of the damask loom became

generally known, however, it was not readily adopted, the machine being

costly and difficult to work. Fifty years after Blake had set up his

machine, there were only ten or twelve damask looms in Dunfermline; and ten

years later, in 1778, the number did not exceed twenty. Three persons were

required to work the loom at first—two weavers, one at each side, to throw

the shuttle and move the "lay," and a boy to work a series of cords which

raised the warp threads necessary to produce the design. Sometimes one man

undertook to work a web two yards wide without an assistant, and in that

case he had to rush from one side of the loom to the other continuously in

order to keep the shuttle going. That was a laborious mode of working; but

it was more profitable than the other system, as, though a smaller quantity

of cloth was produced in a given time, that shortcoming was more than

compensated for by saving the wages of an assistant.

An important improvement was

made on. the damask loom by Mr John Wilson, of Dunfermline, who devised a

mechanical arrangement which dispensed with the services of the draw-boy.

The value of Mr Wilson's invention was publicly acknowledged by his being

made a burgess of the town in 1780; and a further reward was conferred on

him by the Board of Manufactures, who presented him with L.20. As damask was

then woven, it was necessary that the weavers should commit to memory the

details of the patterns; and when a loom was changed from one design to

another, the workmen had to devote four or five days to getting the new

pattern by rote. An error of memory was unfailingly registered in the cloth;

and as the value of the piece was thereby deteriorated, only persons who had

good memories, and who took great pains to learn the patterns, could pass as

efficient workmen. Subsequently an invention was made which rendered it

unnecessary to trust to memory for the proper working of the design. The new

apparatus was known as the "holey-board." In 1803 Mr David Bonnar obtained a

patent for what he called a "comb draw-loom," which had the effect of still

further simplifying the operations of the damask weaver. The trade gradually

increased under these various improvements in the weaving machinery; but it

received its greatest impulse from the introduction of the Jacquard machine

in 1825. By the year 1830 that machine had come into general use. The

advantages derived from the Jacquard machine are numerous; but the most

important are that the facility of production enables the damask

manufacturer to sell his goods at a lower price per yard on the average than

was formerly paid for weaving alone, taking into account also the reduced

price of the raw materials, and that there is no limit to the variety of

designs that may be produced. The designs of the damask made by the old

process were crude and indistinct, but by means of the Jacquard machine the

greatest distinctness of outline and delicacy of detail have been attained.

The Jacquard. machine makes every thread of warp and weft play its part in

the design; but by the " draw" system the pattern was brought out by moving

four or five threads at a time; the result is that the old damask looks as

if the design were worked in mosaic, each spot being a square equal to the

thickness of four or five threads, and in some cases even more. A change of

design was a serious matter for the weaver before the Jacquard machine was

introduced, as the mounting of a fresh pattern occupied five or six weeks,

and during that time he received no remuneration.

When the damask trade had

become fairly established in Dun-fermline, the manufacturers received orders

from noblemen, bishops, and private gentlemen, for sets of table linen

bearing their coats of arms, &c. His Majesty 'William IV. was their first

royal customer, and Queen Victoria had some linen made for her household in

1840. Since the latter date many orders have been received from royal

personages at home and abroad. Great attention has been paid to the

designing department of the trade, which has more than kept pace with the

mechanical improvements. In 1826 a drawing academy was established in the

town, with the view of teaching young men the principles of drawing, and

fitting them to fill the office of designers. The institution did not

succeed, and was given up in 1833. Some designers of eminence were trained,

however, and good resulted to the trade generally. The academy was supported

at the joint cost of the Board of Manufactures and the manufacturers of the

town, who expended L.126 on it annually. The Board also gave premiums for

excellence of design in damask goods, and one firm received L.516, 10s. in

premiums of that kind in eighteen years. Thirty years ago an export trade to

America was opened up by the manufacturers, and about L.150,000 worth of

damask goods found a market in the United States every year. The Americans

have ever since been good customers.

The largest factory in

Dunfermline, and the most extensive of the kind in Britain, is the St

Leonard's Power-Loom Factory, which belongs to Messrs Erskine Beveridge &

Co. The factory is beautifully situated on the south side of the town, and

is in every respect a model establishment. The main building is but one

storey high, and the roof consists of a series of ridges. Externally, the

place is unpretending enough, but there is an air of tidiness and

cleanliness in all its accessories which impresses one favourably. The

coarser sorts of yarn used in the factory are brought from Dundee,

Kirkcaldy, &c., and the finer sorts from Yorkshire and Ireland. Some of the

yarn is received in a brown state, some bleached, and some dyed. Many tons

are kept in stock in rooms set apart for the purpose. The yarn is given out

in hanks to the winders, who, by the use of simple but ingenious machines,

wind it on bobbins for the use of the warpers, or on pirns for the weavers.

The warpers take a certain number of bobbins and arrange them in a frame.

The threads of the bobbins are then led to the warping-machine, in which

they are arranged side by side, and wound with equal strain upon a roller.

One of the great difficulties that had to be overcome by the inventors of