|

ONE of the reasons for Glasgow's

stronger feeling of confidence regarding the issue of the war with

Napoleon may have arisen from the fact that the chief trade of the

Glasgow merchants with the sugar colonies in the West Indies

remained unhurt. Since the destruction of the French and Spanish

fleets at Trafalgar in 18o5 and the capture of the Danish fleet

after the bombardment of Copenhagen two years later, the British

navy had kept the mastery of the seas. Not only was Napoleon's plan

for the invasion of Britain made impossible, but all his efforts to

interfere with British commerce were rendered futile. This was the

snag upon which all Buonaparte's schemes of conquest finally came to

grief. From west to east and from north to south he marched across

the continent of Europe, defeating armies and destroying kingdoms;

but all the time he knew that across the blue waters of the narrow

Channel, behind the cliffs which could be seen from Calais, lay an

enemy whom he could not reach, but who, sooner or later, might send

across an army which would strike a vital blow, and bring to ruin

all the schemes and conquests of his career. This was, of course,

what actually happened in the end, when a British expeditionary army

under Wellington brought his whole ambitious achievement to wreck on

the battlefield of Waterloo.

The consciousness of that possibility, and perhaps the foreboding of

that event, urged him to attempt the destruction of British

resources by a boycott of British trade. The famous decree which he

issued from Berlin in November, 18o6, declared the British islands

to be in a state of blockade. All commerce with Britain was

forbidden, all British goods found in France or the territories of

her allies were subject to confiscation,-and the harbours of these

countries were closed against all British vessels, or vessels which

had touched at British ports. Napoleon, however, had no fleet with

which to enforce these edicts, and as a matter of fact the countries

of the continent could not very well, just then, get along without

British manufactures. The Berlin decrees were made entirely

ineffectual by a few daring British traders, who proceeded to set up

a great contraband system for running British goods across the

frontiers.

Among these contraband traders

perhaps the most daring and successful was a Glasgow merchant.

Kirkman Finlay was a member of a family which, like the Buchanans, a

century earlier, came from the neighbourhood of Killearn. [A very

full account of the Finlays and all their family connections is

given in J. O. Mitchell's Old Glasgow Essays, p. 26.] His father,

James Finlay, was the fourth son of John Finlay of The Moss,

birthplace of the famous Latinist of Queen Mary's time, George

Buchanan. Coming to Glasgow he founded the business of James Finlay

& Co., in Bell's Wynd, now Bell Street, off Candleriggs. In the

procession, already described, which beat up for recruits for the

American war in 1778, he is said to have been the "gentleman playing

on the bagpipes," and in the list of subscriptions the name of James

Finlay & Co. is down for fifty guineas. [Glasgow Mercury, 29th Jan.,

1778. Senex, Old Glasgow, p. 169.]

Kirkman was James Finlay's younger

son, and carried on the family business. He got his somewhat curious

Christian name from Alderman Kirkman, his father's London

correspondent and friend. In 1793, three years after his father's

death, he bought the cotton mills of Ballindalloch on the Endrick

from his relatives, the Buchanans; in 1801 he bought the mills at

Catrine in Ayrshire from David Dale and Alexander of BaIlochmyle;

and in z8o8 he bought Deanston mills on the Teith from their Quaker

owner, Benjamin Flounders. [Old Glasgow Essays, p. 33.] He was also,

however, a merchant, and it was Napoleon's Berlin decree which gave

him his great opportunity. Aware that a ready market awaited our

manufactures if they could be smuggled into the Continent, he

established depots in Heligoland and elsewhere at strategic points,

and organized a great system of contraband in which, if the risks

were great, the rewards were correspondingly high. In that bold game

he must be held to have fairly beaten his powerful opponent,

Napoleon himself. It is said that the Emperor's own troops were clad

in overcoats made at Leeds, and marched in shoes made at

Southampton. [Green, Short History, p. 823.] The result shewed the

world that British commerce was beyond Napoleon's power to ruin, and

the blow thus struck at the Emperor's prestige, with the service

rendered to British industry, contributed not much less to the

overthrow of the dictator than the defeat of his military forces by

the Duke of Wellington.

Kirkman Finlay also played a notable

part in the overthrow of another monopoly. For two hundred years,

since it received its charter from Queen Elizabeth, the East India

Company had enjoyed a monopoly of all the trade of this country to

the east beyond the Cape of Good Hope. From time to time the charter

fell to be renewed. This had been done in 1749. and in 1780, largely

by dint of immense loans to the Government. When the charter again

approached expiration in 1812 Kirkman Finlay induced the Town

Council of Glasgow to enquire into the conditions. [Burgh Records,

8th and 24th Jan., 20th March, 19th May, 9th June, 1812. Later, in

1830, the Town Council again made appeal to Parliament against

renewal of the exclusive privileges of the East India Company.—Burgh

Records, 26th Feb., 1830.] In the Indian and Pacific Oceans he saw

vast possibilities for extending the commerce of Glasgow, and no

sooner was the trade thrown open than he freighted the "Earl of

Buckinghamshire" and sent it out to Bombay. That vessel, of 600

tons, which was despatched in 1816, was the first to sail direct

from the Clyde to an eastern port. In the following year Kirkman

Finlay sent out the "George Canning" the first Glasgow ship for

Calcutta; and in 1834 he ventured still further, and despatched the

"Kirkman Finlay," the first Glasgow ship for China. [Table of Dates

in Old Glasgow Essays, pp. xlii and xliii.] Thus, by his courage and

enterprise, he opened up the great trade with the Far East which has

brought an endless stream of prosperous commerce to the Clyde.

Under its shrewd and far-seeing chief

the firm of James Finlay & Co. carried on a vast business. In the

course of a legal case it was shewn that the profits of the firm in

twenty years amounted to more than a million sterling. For his

Glasgow hrnise Kirkman Finlay bought the fine mansion of James

Ritchie of Busby, the Virginia "tobacco lord," on the west side of

Queen Street, [Depicted in Stuart's Views and Notices of Glasgow.]

and on the Firth of Clyde he set a fashion by forming and planting a

noble estate and building the mansion of Castle Toward. Personally

he was of the finest type of Glasgow merchant, liberal and kindly, a

generous master and a fair opponent, whose word was as good as his

bond. [Old Glasgow Essays, p. 34.] In addition to his own business

he took an active part in public affairs. He was Governor of the

Forth and Clyde Navigation, President of the Chamber of Commerce,

Lord Provost, Lord Rector of the University and Dean of Faculties

thereof. In 1812, when he was elected Member of Parliament, the

enthusiasm of the citizens passed all bounds. They paid his expenses

and struck a medal in his honour, drank his health with cheers and

applause in front of the Town Hall at the cross, and, unyoking his

horses, dragged him in his carriage to his own house in Queen

Street. Alas, however, for the fickleness of fame! three years later

they paid him another visit. He had voted in parliament for

Prosperity Robinson's Corn Bill, and, finding him from home, they

attacked his house and smashed his windows, pelted with mud and

stones the horse patrol which was turned out to disperse them, and

were only brought to reason by the arrival of a detachment of the

71st Foot and by two troops of cavalry from Hamilton. That, however,

is the way of the "profanum vulgus." When Kirkman Finlay died at

Castle Toward he was buried with much honour in Blackfriars Aisle at

the cathedral, and a statue of him, by Gibson, was set up in the

vestibule of the Merchants House. [Ibid. pp. 34, 35. Curiosities of

Glasgow Citizenship, p. 207.]

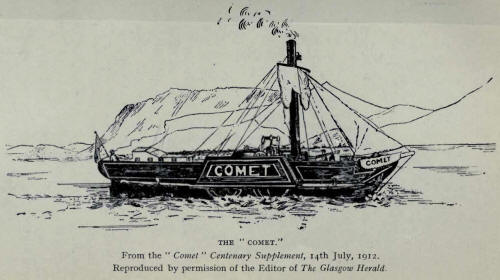

It was in the year in which this very

notable Glasgow merchant was elected Member of Parliament that Henry

Bell placed his " Comet " on the waters of the Clyde: - Hardly could

a greater contrast be found than that between the humble projector

of steam navigation in this country and Kirkman Finlay with his

great schemes of commerce which played a part in destroying Napoleon

and in opening the eastern world to Glasgow trade. Henry Bell was

not, of course, the inventor of the steamboat. ` He was not even the

first to put a practical and successful steamer on British waters.

As early as the year 1543 Blasco ,de Gary is said to have launched a

boat propelled by a jet of steam on the harbour at Barcelona. In

1707 Denis Papin, inventor of the atmospheric engine, placed a

paddle-boat on the river Fulda at Cassel; and in 1736 Jonathan Hulls

patented a form of paddle-steamer in England. After the improvement

of the steam engine by James `Vatt, attempts, more or less

successful, were made, in France by the Marquis de Jouffroy in 1783,

and in America by James Rumsey in 1786 and by John Fitch in 1787.

One of Fitch's boats attained a speed of seven miles an hour, and

plied as a passenger steamer on the Delaware. In Scotland the first

practical application of steam to the propulsion of vessels was made

by Patrick Miller, the retired banker, on the little loch on his

estate of Dalswinton, in Dumfriesshire, in 1788, in the presence of

no less notable persons than Robert Burns, Nasmyth the painter, and

the future Lord Brougham. The application of steam to the

paddlewheels, with which Miller had been experimenting, was made on

the suggestion of James Taylor, his family tutor, and the engine was

constructed by William Symington, a native of Lead-hills. In the

following year Miller had a more powerful vessel built at Carron

Ironworks, which attained a speed of seven miles an hour on the

Forth and Clyde Canal. Thirteen years later Symington was in the

field again. Commissioned by Thomas, Lord Dundas, in 1802 he placed

a stern-wheel steamer, the "Charlotte Dundas," on the canal. The

vessel towed two laden barges of seventy tons each a distance of

twenty miles against a strong head wind in seven hours, and must be

considered "the first practically successful steamboat ever built."

Her performance on the canal was only stopped because the wash of

the paddles threatened to destroy the banks. Meanwhile the little

ship had been inspected by two ingenious individuals, Robert Fulton

and Henry Bell. The former, after experimenting with a steamboat on

the Seine in 1803, launched on the Hudson in America in 1807 the

steamer "Clermont," which was the progenitor of all the steamship

enterprise of the New World. [Symington, Brief History of Steam

Navigation.]

Henry Bell, who, five years later,

played the same part in the steamship enterprise of this country,

was a native of the little old-world village of Torphichen, near

Linlithgow. He learned in succession the crafts of stone-mason,

mill-wright, and shipbuilder, and was employed for a time in London

by Rennie the celebrated civil engineer. In 1790 he set up in

business in Glasgow as a wright or house carpenter. His brain,

however, was full of ambitious projects in other fields, and in 1800

and 1803 he approached the Government with schemes of steamship

construction. Lord Melville and James Watt both discouraged the

idea, and, though Lord Nelson declared strongly in its favour,

nothing came of the application. Bell does not appear to have made

much of his business as a wright in Glasgow, and in 1807 his wife

undertook the superintendence of the public baths at Helensburgh,

then recently founded by Sir James Colquhoun at the mouth of the

Gareloch. Beside the baths she carried on an inn, the Baths Hotel,

and it was in the interest of this undertaking, and of the little

burgh, of which he was provost from 1807 till 1809, that Bell at

last turned his speculative ideas to practical account. - In 18rz he

induced John Wood & Co. of Port-Glasgow to build a vessel for him.

The engine was made by John Robertson & Co. and the boiler came from

the foundry of David Napier in Glasgow. The "Comet," named from a

celebrated comet which appeared in the heavens at that time, was

launched with steam up on 18th January 1812, and proved its success

by steaming at five miles an hour against a head wind. In August it

was advertised to sail "by the power of air, wind, and steam," three

times a week from Glasgow to Greenock and Helensburgh, and in

September the voyage was extended to Oban and Fort William. [A full

account of Henry Bell's undertaking and the rapid development of

river steamer enterprise which followed will be found in Captain

James Williamson's volume, The Clyde Passenger Steamer.]

CAPTAIN

JAMES WILLIAMSON CAPTAIN

JAMES WILLIAMSON

For half a century the passenger steamer enterprise of the Clyde has

been more or less a family affair, Williamsons, Campbells, Buchanans,

MacKellars, and MacBraynes of successive generations having most of

it in their hands. Nor has the modern advent of the railway

companies' fleets made any change in this respect, for three of

these fleets are managed by Williamsons at the present day.

The secretary and manager of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company,

eldest of this family, was born at Millport, and educated at

Rothesay and Hutton Hall, Dumfries. He began life as an apprentice

in the Dock Engine Works of Messrs. William King & Co., Glasgow,

with a view to practical acquaintance with the vital part of the

steamers he was afterwards to command. At the end of his

apprenticeship he joined his father, owner of the Sultan, Sultana,

and Viceroy, otherwise known as the "Turkish Fleet" among the river

steamers, and when placed in command of the Sultana he was probably

the youngest captain who ever trod a bridge. One of his achievements

in this position was to reduce the journey from Wemyss Bay to

Rothesay and Millport by forty minutes. He became famous on the

firth for his decision and daring in the handling of his craft, and

many incidents are recorded of his outmanoeuvring his rivals.

In 1879 Captain Williamson, with a few prominent shipowners, built

the Ivanhoe as a temperance steamer, and under his command she was

one of the most successful crafts on the firth. As part of her

programme he initiated the evening trips and other attractions which

have since become so popular. At the same time he joined in setting

up the firm of Morton & Williamson, consulting engineers and marine

surveyors, as a means of occupying his time in the "off" months. In

1885, on a visit to Melbourne, he saw room for enterprise in the

steamer trips there, and in the following year sent out a crack

steamer which revolutionised the running in colonial waters.

In 1888 the Caledonian Railway Company, on the eve of completing its

extension to Gourock, invited proposals from the steamboat owners

for the development of the coast traffic. Jealousy of the new

venture made all the others hold back, but Captain Williamson

formulated a plan, and the result was the formation of the

Caledonian Steam Packet Company on the lines which he suggested, and

his appointment as its Secretary and Manager. The success of the

enterprise has justified his advice. Captain Williamson must be

credited, not only with an immense share in the improvement of the

Clyde steamer, but also with the marked raising of tone among the

officers and crews.

In 1904 he published a highly interesting and valuable book, "The

Clyde Passenger Steamer, its Rise and Progress during the Nineteenth

Century, from the Comet of 1812 to the King Edward of 1901," which

forms a complete compendium of its subject, and is likely to remain

its vade mecum.

Bell himself made little of his

enterprise. Some of his bills remained unpaid; but he was the

pioneer of a great development for Glasgow and the Clyde. [During

the ten years which followed the launch of the "Comet" no fewer than

forty-eight steam vessels were constructed in shipbuilding yards on

the Clyde.—Mackinnon, Social and Industrial History, p. 95.] In view

of this, on his approaching old age a subscription was raised on his

behalf, which realized a considerable sum, while the Clyde Trustees

granted an annuity of 100, which was continued to his widow. After

his death in 1830 an obelisk to his memory was built at Dunglass

Castle on the riverside above Dunbarton, and in 1872 another was

erected on the esplanade at Helensburgh. His dust rests in Rhu

churchyard.

A man to whom Glasgow and the Clyde

owe much more than they do to Henry Bell was David Napier, the maker

of the boiler for the "Comet." Besides the workshop in Howard

Street in which that boiler was made, Napier had a foundry at Camlachie, and he is said to have used the Camlachie Burn as an

experimental tank for testing the comparative merits of the models

of his ships. In this way he ascertained the best shape, the clipper

bow, for ocean going steamers, and among his other inventions was

the "steeple engine," which took the place of the old and awkward

beam-engine on board ship. He placed steam carriages on the roads,

and a fleet of river steamers on the Clyde; he placed the first

steamers on Loch Lomond and Loch Eck, and he opened up the Loch Eck

route to Inveraray. His cousin, Robert Napier of Shandon, who

succeeded to his business when he went to London, enjoys most of the

credit to-day; but David Napier was the actual pioneer of the modern

shipbuilding industry of the Clyde. [David Napier, Engineer. The

Clyde Passenger Steamer, pp. 52, 70.]

Presently iron was substituted for

wood in the Clyde shipbuilding yards. The first boat made of iron in

Scotland was the "Vulcan" which was built in 1817 at Faskine on the

Monk-land Canal by Thomas Wilson, and which, two years later, began

service as a passenger vessel on the Forth and Clyde Canal. The

first iron steamer was the "Fairy Queen," built by Neilson at the

Oakbank Foundry, Glasgow, carted to the Clyde, and launched at the

Broomielaw in 1831. Since then the development of Glasgow's overseas

trade and of Clyde-built ships and engines which ply on every ocean

of the world, has been almost beyond belief, and the city does well

to remember what it owes to the initiative of Kirkman Finlay, David

Napier, and Henry Bell. [A highly interesting detailed account of

the development of ship building on the Clyde is furnished by

Professor Mackinnon in his Social and Industrial History of

Scotland, p. 93.]

|