|

THE period of King

James's reign which followed his return from England is marked by

much legislative activity and in this connection the burghs were not

overlooked. Under statutes then passed regulations came into

operation for the more effective supervision of craftsmen and their

work; hostels or public inns were to be provided for the

accommodation of travellers; burgesses and indwellers, sufficiently

equipped, had to appear for inspection of their armour, at the

periodical wapinshawings; measures were to be adopted for security

against fire; the "array of burgesses and thair wyffis" was

regulated by the sumptuary laws; rules were laid down "anent Lipper

folk"; beggars were subjected to licensed conditions; playing at

football was discouraged as interfering with the practice of

archery, and instructions were given to the king's officers and

burgh sergeants for the maintenance of order.

By a parliament held

on 26th May, 1424, a subsidy was imposed to meet the contribution to

England stipulated for on the return of the king from captivity. As

Glasgow bore its share of the taxation for King David's ransom it

might have been expected that the burgh would also be a contributor

to the levy of 1424, but in the Exchequer Rolls, where the

contributions of twenty-three burghs are recorded, Glasgow is not

included in the list.

Acts of parliament

were passed for securing the "fredoine of halikirk"; traffic in

pensions payable out of church benefices was prohibited; church

lands unjustly alienated were to be restored; and churchmen were

forbidden, by themselves or their procurators, to take their law

pleas to foreign ecclesiastical courts without the king's consent.

These and other regulations, however needful and salutary, did not

meet with approval in all quarters, and the responsibility for their

introduction having to some extent been ascribed to John Cameron,

who was Bishop of Glasgow from 1426 to 1446, he was subjected to not

a little opposition and trouble on that account.

It is not known if

King James ever held court in, or even passed through Glasgow,

though, keeping in view the long official, as well as personal,

intimacy which subsisted between him and Bishop Cameron, it is

likely enough that he was an occasional visitor. The bulk of the

king's charters, so far as recorded in the Great Seal Register, were

granted at Edinburgh, and a large number are dated from Perth, but

Glasgow is not one of the eight towns from which the remainder

emanated. So far as has been noticed, the only charter of James,

connected with Glasgow, is one granted under his privy seal, at

Edinburgh, on 14th April, 1426, whereby, in consequence of the see

being vacant at the time, he presented Thomas Pacock, priest, to a

chaplainry in the cathedral founded by Bishop Lauder.

The appointment to

the see, which fell vacant through the death of Bishop Lauder, on

14th June, 142.5, had been specially reserved to the Pope, but, in

ignorance of the reservation, the chapter elected John Cameron as

bishop. On all the circumstances being represented to the Pope he,

on 22nd April, 1426, assented to the choice made by the chapter and

subsequently authorised the consecration of the new bishop. Still it

appears that in these arrangements entire harmony did not prevail.

In a papal bull, issued in May, 1430, it is stated that Cameron had,

before his promotion, incurred disability more than once, and by

subsequent action in parliament had been the author of statutes

about collation to benefices which were against ecclesiastical

liberty and the rights of the Roman Church, transgressions which had

resulted in his excommunication. Through the intervention of the

king on the bishop's behalf, and after an investigation, in the

course of which the accuracy of many of the charges was disputed,

while proper behaviour was promised in the future, the bishop was

absolved from the sentences which had been pronounced against him. [Dowden's

Bishops, pp. 319-22. rrevious to his appointment as bishop, Cameron

had been a canon of Glasgow, provost of Lincluden, king's secretary

and official of St. Andrews. (See also Medieval Glasgow, pp. 6o el

seq.)]

On this as well as on

subsequent occasions when the bishop had to defend himself against

accusations lodged at the papal court, one of his chief accusers

seems to have been William Croyser, Archdeacon of Teviotdale.

Between the bishop and the archdeacon there had been a controversy

with regard to the jurisdiction exerciseable by the latter; and the

dean and chapter, to whose arbitration the dispute had been

referred, pronounced a decree on 14th January, 1427-8, whereby it

was found that the bishop was entitled to have his commissaries

throughout the whole diocese, qualified to decide all causes to the

same extent as in the archdeanery of Glasgow. The commissaries

appointed by the Archdeacon of Teviotdale were entitled to hear and

decide all minor causes within their jurisdiction, but the

archdeacon had no power to dismiss or incarcerate the clerks in his

archdeanery or to appoint them to or deprive them of benefices

without the special authority of the bishop. It was also declared

that the losers in causes ,decided by the archdeacon or his

commissaries should have recourse by appeal to the bishop or his

auditor. [Reg. Episc. No. 332. Croyser was deprived of the

archdeaconry in or about the year 1433, but it was subsequently

restored to him, and by the decision of the dean and chapter in 1452

it was declared that the Archdeacon of Teviotdale had precisely the

same jurisdiction in his district as the Archdeacon of Glasgow had

in his part of the diocese (lb. No. 373. See also 'James I., Bishop

Cameron and the Papacy " in the Scottish Historical Review, vol. xv.

pp. 190-200).]

Bishop Cameron held,

successively, the offices of secretary of state and keeper of the

privy and great seals. He was chancellor of the kingdom from 1426 to

1439, and he also served on several embassies to England ; but

notwithstanding the calls upon his time involved in the performance

of official duties and the unpleasant interruptions arising out of

his contests with ecclesiastical superiors and others, diocesan

affairs, and especially those connected with the cathedral, were

attended to with conspicuous efficiency. To the cathedral chapter

already embracing twenty-six members, he procured an addition of

seven prebends, and passed a series of statutes, regulating the

attendance and duties of the canons, and the yearly sums payable by

them to their vicars, and he ratified the ordinance issued by Bishop

Matthew in 1401 for payment of certain sums on admission of

prebendaries in order to provide the vestments and ornaments needful

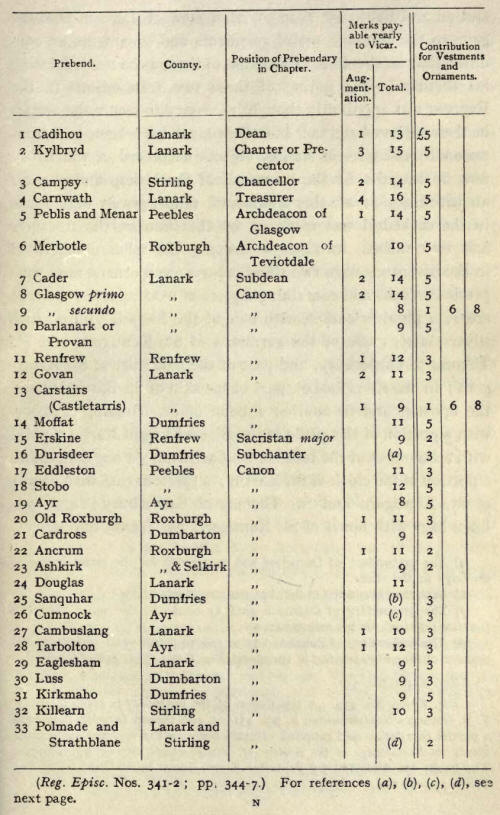

for service in the cathedral. [For a list of the prebends in Bishop

Cameron's time see p. 193.]

The term vestments

and ornaments, as used in Registrum Episcopatus, included the

necessary equipment and furniture of the cathedral, whether of a

decorative character or not, and as considerable expenditure was

incurred in procuring and upholding these the money raised from

taxed prebends would have been insufficient for the purpose unless

supplemented by gifts from pious benefactors. A donation obtained

from Walter Fitz-Gilbert in 1320 has been already referred to; [Antea,

p. 149.]

(a) The prebendary of

Durisdeer had to provide for the maintenance of six boys in the

choir.

(b) Sanquhar is entered in list, but the sum is left blank.

(c) The prebendary of Cumnock paid II merks to the inner sacristan (sacriste

interiori) for his maintenance.

(d) The prebendary of Polmade had to pay 16 merks yearly for the

maintenance of four boys serving in the choir (Reg. Episc. Nos. 338

and 341).

and on 2nd February,

1429-30, Alan Stewart, Lord of Dernele, gave to the church a set of

vestments and ornaments on condition that he should have such use of

them as he needed during his lifetime. [Reg. Episc. No. 337.] The

noting of these two transactions in the Register was apparently

thought necessary to secure the donors in their reserved rights; but

there must have been numerous unconditional gifts of similar objects

no record of which can now be traced. At the command of the bishop

and chapter an inventory of all the ornaments, relics, jewels and

books in the cathedral was made up by the chanter, the treasurer and

two canons, in 1432-3. [Reg. Episc. No. 339. A translation of the

inventory is given in Dr. J. F. S. Gordon's Scotichronicon, ii. pp.

451-7; and Bishop Dowden has given a partial translation and

supplied valuable notes on the vestments and ornaments in

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, 1898-9, pp. 280-329. The

books are described by Professor Cosmo Innes in his Preface to Reg.

Episc. pp. xlii-xlvi.] Among the relics enumerated in the inventory

were two silver crosses, each ornamented with precious stones and

containing a piece of wood, part of the true cross; a phial or

casket, with hair of the Blessed Virgin; in a silver coffer, parts

of the garments of St. Kentigern and St. Thomas of Canterbury, and

part of the hair shirt of St. Kentigern; in one silver casket, part

of the skin of St. Bartholomew, the apostle, and in another a bone

of St. Ninian; a casket with a portion of the girdle of the Blessed

Virgin Mary; a phial with a fragment of the tomb of St. Catherine; a

bag containing a portion of the cloak of St. Martin; a precious case

with combs of St. Kentigern and St. Thomas of Canterbury; and two

linen bags with bones of St. Kentigern, St. Tenew, and several

saints. At the Reformation most of the relics and jewels were

carried to France by Archbishop Beaton, and such of them as were not

otherwise removed for safety, and were found about the cathedral,

ran the risk of being destroyed as objects of idolatry.

The parishes which,

by Bishop Cameron's additions, had their rectors constituted members

of the cathedral chapter were Cambuslang and Eaglesham in the county

of Lanark, Tarbolton in Ayrshire, Luss in Dumbartonshire, Kirkmaho

in Dumfriesshire and Killearn in Stirlingshire. [The patrons

consenting to the erection of these prebends were Archibald Earl of

Douglas for Cambuslang, Sir John Stewart of Dernlie for Tarbolton,

Sir Alexander Montgomery for Eaglesham, John Colquhoun, Lord of Luss,

for that parish, Sir John Forestar and his lady, Margaret Stewart

with Sir William Stewart, her son, for Kirkmaho, and Patrick Lord

Graham for Killearn (Reg. Episc. Nos. 336 and 340; also, vol. i. p.

xlii.).] The remaining new prebend was in a peculiar position. Some

particulars have already been given about the Hospital of

Polmadie.io At a conference held in the chapel on the west side of

Edinburgh Castle, on 7th January, 1424-5, the Earl of Lennox

acknowledged that the Bishop of Glasgow had full right to the

patronage of the hospital with its annexed church of Strathblane,

and he accordingly resigned any claim he had in favour of Bishop

Cameron and his successors. [Antea, pp. 147-8, 158, 163. 'Reg. Episc.

No. 344.] Having thus obtained a free hand in the disposal of these

endowments, Bishop Cameron, with consent of his chapter, erected the

hospital and church into a prebend of the cathedral, stipulating

that the church should be served by a vicar, to whom should be paid

14 merks yearly besides getting the use of about thirty acres of

land as a glebe. [Reg. Episc. p. ci; letters by the bishop and

chapter dated 12th January, 1427-8 ; ratified by a papal bull dated

5th December, 1429; Ib. No. 338.] It is not known if the hospital,

as a refuge for poor men and women, was now discontinued, but even

as a prebend of the cathedral its connection with Glasgow was soon

severed. In 1453 Isabella, Countess of Lennox and Duchess of Albany,

founded the collegiate church of Dumbarton; and by some arrangement,

to which the Bishop of Glasgow must have been a party, though

particulars of the negotiation have not been discovered, the whole

endowments of the hospital were transferred to the Collegiate

church.

Most local

historians, following the lead given by John M'Ure, state that the

building of manses for the prebendaries originated with Bishop

Cameron, but in reality these churchmen, bound to give attendance at

the cathedral during a considerable part of each year, must always

have had suitable residences in Glasgow, and it is probable that the

arrangement proposed in 1266, whereby the bishop then to be

appointed was required to provide such additional space as might be

required for the erection of manses, was substantially carried into

effect about that time. Of the few recorded notices bearing on the

possession of prebendal manses there is the narrative of an inquiry

which took place in the chapel of Edinburgh Castle on 2nd March,

1447-8, for the settlement of a controversy between Mr. John Methven,

canon of Glasgow, and Sir John Mousfald, chaplain, as to the

ownership of a tenement on the north side of Ratounraw. The

arbiters, consisting of Lord Chancellor Crichton and others, found

that Mr. John had full right to the tenement as being annexed and

belonging to the prebend of Edilston. At that time Methven was

apparently prebendary of Edilston and thus entitled to occupy the

tenement as his manse, a building about which some interesting

particulars of later date have been collected.

The great stone spire

of the cathedral, from the level of the parapet of the central

tower, was placed by Bishop Cameron, and he also completed the

chapter-house, on one of the carved bosses in the vaulting of which

his arms are shown. The erection of the consistory house and

library, an oblong structure of two storeys, which, with the

addition of a third storey added in the seventeenth century, formed

the south-west tower of the cathedral, is also believed to have been

accomplished in the bishop's time [Glasgow Cathedral (1901), pp. 17,

19; (1914), pp. 25, 26. As mentioned, antea, pp. 128-9, it has been

suggested that the south-west tower may have been so far erected in

Bishop Robert Wischart's time.]; and, not confining his building

activities to the cathedral and its accessories, Cameron made an

addition to the adjoining episcopal residence by adding the tower,

which, according to M`Ure, bore his name and on which his arms were

visible in 1736. [Mediaeval Glasgow, p. 77. Dr. Primrose points out

that the tower erected by Bishop Cameron was not, as generally

supposed, at the southwest angle of the wall facing Castle Street,

but was placed towards the east within the palace grounds.]

As territorial lords

the bishops had several grain mills throughout the barony. A mill on

the River Kelvin served the Govan and Partick wards. Baddermonach

ward, corresponding to the modern Cadder parish, had its mill at

Bedlay, and Clydesmill supplied the wants of Cuik's ward or West

Monk-land. Two of the cathedral prebends also had mills as part of

their endowments—the barony of Provan having its mill on the

Molendinar Burn, and farther down the stream, at the foot of Drygate,

the subdean having his mill, for the grinding of grain from his own

lands and perhaps from others within the thirl.

So far as has been

ascertained the burgesses of Glasgow, previous to the fifteenth

century, were thirled to no mill in particular, and it is not till

some years later that we have definite knowledge of the means

provided for grinding their grain. Originally hand mills may have

supplied all demands, but, in the interest of those overlords who

possessed water mills, burgh laws of the thirteenth century forbade

the use of hand-mills unless they had to be resorted to in

consequence of great storms or want of water. In any case, it may be

assumed that this primitive process would be superseded at an early

date, and that the bishops would see to the supply of the requisite

grinding facilities at one or other of the mills on the Molendinar

Burn. At length a definite arrangement was concluded with Bishop

Cameron whereby the burgesses and community were empowered to

construct a mill on their lands of Garngadhill, on the north side of

the Molendinar Burn, in consideration of their contributing two

pounds of wax, yearly, for the lights around the tomb of St.

Kentigern in the cathedral. These facts are ascertained from a

document which is still preserved, being a Notarial Instrument,

dated six weeks after the bishop's death, and certifying that the

keeper of the lights acknowledged the yearly delivery of the

specified quantity of wax from the time when the arrangement was

made, a date, however, which is not given. [Glasg. Chart. i. pt. ii.

pp. 25-27 (4th February, 1446-7).]

From another source a

further supply of lights was secured for the cathedral. Lands called

at one time Collinhatrig, afterwards Conhatrig and now Conheath, in

Dumfriesshire, formerly belonged to the Bishops of Glasgow, and

under an arrangement between the Duke of Albany, then governor of

the kingdom, and Bishop William, the revenues were annexed to the

Hospital of St. Leonard in Ayrshire. But by a charter, dated 7th

June, 1442, King James II. dissolved this union, and the rights in

the lands were restored to Bishop Cameron, who bestowed the rents on

the cathedral for the better supply of wax and upkeep of lights; and

he also stipulated that any surplus of income should be applied in

providing white lawn and other ornaments of the high altar. [Reg.

Episc. No. 347; also p. cii. The yearly feuduty payable to the

archbishop for the lands of Conhatrig in 1632 was 3 6s. 8d.

(Descriptions of sheriffdomns of Lanark and Renfrew (1831), p.

149).]

Bishop Cameron also

instituted a mass to be called the Mass for the Dead Bishops and to

be celebrated by the vicars of the choir and the four boys of the

Polmadie prebend. For their services the vicars were to be paid

eighteen merks yearly out of the ferms of the burgh of Glasgow,

[Reg. Episc. p. cii.] a most interesting stipulation, on the working

out of which information would have been welcome. The only burgh

ferm payable to the bishops, of which we have any trace, was that of

sixteen merks for the lands possessed by the burgesses; but,

following the practice prevailing in royal burghs, additional "ferms"

were probably exacted for customs and other dues leased to the

community. Out of these combined revenues the vicars might draw

their annual allowance of eighteen merks. [During the English

occupation King Edward's collectors, in 1302-4, took £48 6s. 8d. and

40s. from the burgh ferms. Bain's Calendar, ii. p. 424; antea, p.

141.]

According to a

tradition which George Buchanan says was current in his time, Bishop

Cameron had the reputation of dealing harshly with his rentallers,

[Buchanan's History of Scotland, 1821 edition, vol. ii. book xi. p.

225.] but this may imply no more than that he took greater care than

some of his predecessors had done to collect his yearly revenues as

well as to exact the occasional heavy fines or casualties falling

due on renewals of investiture. The agreement with the burgesses as

to the town mill may be regarded as an example of the bishop's

methodical way of transacting business; and if previous bishops had

not already begun to keep the rental books, of which specimens are

still preserved, bearing dates between 1509 and 1570, it is not

improbable that Cameron introduced the system. Buchanan also states

that the bishop was reported to have died, under mysterious

circumstances, "in a farm of his own, about seven miles from

Glasgow," on Christmas eve, 1446. Subsequent writers assume this

"farm" to have been the bishop's manor-house of Lochwood, which was

situated about six miles east of the cathedral. But grave doubt is

cast on the accuracy of the story, not only on account of its

inherent improbability, but also by the following entry in the

Auchinleck Chronicle (p. 6), which is regarded as containing a

contemporary narrative of events :—" Ane thousand iiii ° xlvj. Thar

decessit in the Castell of Glasqw, master Jhon Cameron, bischop of

Glasqw, apon Yule ewyne, that was bischop xix yere." Besides,

tradition was not altogether one-sided in its dealing with the

bishop's character. John M'Ure, who wrote in 1736, found it hard to

credit the story recounted by the earlier historians about Cameron,

"from what good things we hear " about him. Viewed from M'Ure's

standpoint the extortionate laird getting in his "racked rents" from

"poor tenant bodies, scant o' cash," is transformed into the "great

prelate, seated in his palace," and bounteously distributing favours

among " his vassals and tenants, being noblemen and barons of the

greatest figure in the kingdom." [M`Ure's History of Glasgow (1830

edition), pp. 18-20, 48.] Exaggeration seems apparent in both

accounts, but the fact of these being in circulation at so great

distances of time bears witness to the exceptional influence

exercised by Bishop Cameron while he ruled the see.

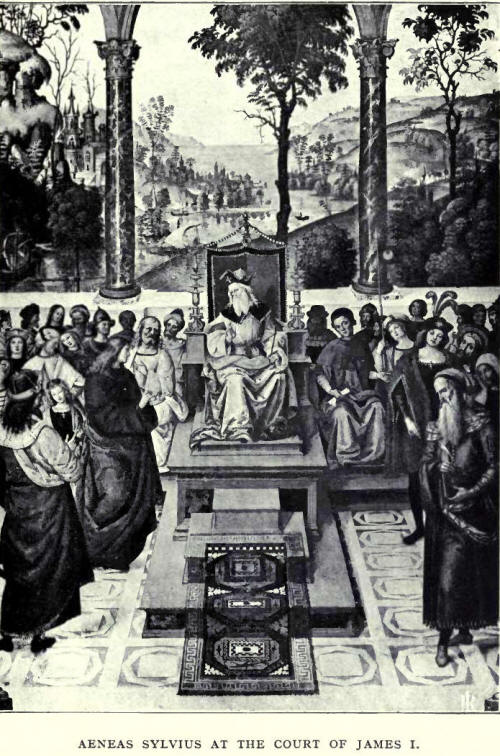

In the reign of James

I. Scotland was visited by two observant strangers, one from the

continent and the other from England, each of whom has left a record

of his impressions of the country, in general, and the Englishman

likewise refers to Glasgow in particular. Æneas Sylvius, afterwards

Pope Pius II., was a guest at the king's court in the winter of

1435, and he describes Scotland as a cold, bleak, wild country,

producing little corn, for the most part without wood, but yielding

a "sulphurous stone " which was dug out of the earth for fuel. The

cities had no walls, the houses were mostly built without lime, with

roofs of turf in the towns. Hides, wool, salt fish and pearls, were

exported to Flanders. [Hume Brown's Early Travellers in Scotland,

pp. 25-27.] Though there is no evidence that Glasgow came under the

notice of this keen observer most of his quoted remarks may be

adopted as applying to its condition at that time, including the

allusion to coal digging, which was then probably carried on in open

quarries.

The other visitor

just referred to was John Hardyng, who was sent to Scotland by Henry

V. and Henry VI. of England, to procure deeds confirming the claims

of English superiority over Scotland, and who, being unsuccessful in

the search, returned with documents suspected to be of his own

manufacture, but which he stated had been procured by purchase in

fulfilment of the purpose of his mission. In his metrical Chronicle

which propounds different schemes for the conquest of Scotland,

Hardyng has the following remarks on Glasgow:

"Returne agayne unto

Strivelyne,

And from thence to Glasco homewarde,

Twenty and foure myles to S. Mongo's shrine,

Wherewith your offeryng ye shall from thence decline,

And passe on forthwarde to Dumbertayne,

A castell stronge and harde for to obteine.

In whiche castell S. Patryke was borne,

That afterwarde in Irelande dyd wynne...

.... Than from Glasgo to the towne of Ayre,

Are twentie myles and foure wele accompted,

A good countree for your armye everywhere

And plenteous also, by many one recounted ...

.... Next than from Ayre unto Glasgew go,

A goodly cytee and universitee,

Where plentifull is the countree also,

Replenished well with all commoditee."

A plan is sketched

for three armies traversing the country in a sort of conquering

march and all three meeting at

"Glasgo

Standyng upon Clyde, and where also

Of corne and cattell is aboundaunce,

Youre armye to vittayle at all suffysaunce."

The Chronicle was

written by Hardyng in his advanced age, and some of his remarks,

such as his allusion to the "universitee" of Glasgow, are applicable

to a period later than the reign of the first James. But in any

case, the Englishman's observations convey the impression that in

the first half of the fifteenth century the country was in a fairly

prosperous condition. |