|

The pedestrian plodding wearily along the highway,

after a lengthened and devious walk, when some gay equipage dashes rapidly

past, spattering the mud around, or leaving a blinding cloud of dust along

its track, is apt to feel a passing twinge of envy, and to fancy that

their lot must indeed be a happy one who possess so handsome and luxurious

a conveyance. He is ready under such circumstances to exclaim, "How much

is their mode of progression as a means of enjoyment superior to mine!"

Yet there cannot be a greater mistake. For speedy transmission from point

to point on matters of business, or for the salutary airing of an invalid,

the various equestrian methods of transport may be all very well; but for

healthy exercise of the person, and the thorough enjoyment of nature,

there is nothing that can for a moment bear comparison with natural

locomotion. The man who travels by carriage must keep by the highway; he

cannot plunge into the recesses of the wood in search of the wilding

flower; the din of the wheels on which he is borne along drowns the sweet

voices of the birds. He cannot follow the windings & the footpath through

the whispering corn-field, nor trace that fairest line of beauty, the

"trotting burn’s meander," which, according to the bard of Coila, forms

the favourite haunt of the Parnassian sisters. Then he is continually

liable to interruption from the outstretched hand of the toll-keeper; his

horses are always getting rid of their shoes at out-of-the-way places,

where farriery is an art unknown, or his driver, taking a cup too much, is

sure to run over and squelch some unlucky urchin making mud-pies on

the middle of the road, or to come tilt

against a mile-stone and spill his unfortunate master, who, if he escapes

with nothing worse than a dislocated shoulder or a fractured collar-bone,

may thank his stars, and consider himself an exceedingly lucky fellow.

Really, amidst all our troubles— and we suppose everybody has his share—we

have much reason for gratitude to Fortune, that she has not inflicted on

us a carriage and its cares; and that without encumbrance, save our gray

hazel switch, we

"Can wander away over hill and glen,

Far as we may for the

gentlemen."

There are several ways

which the pedestrian may take at pleasure in his rambles from Glasgow to

Cathcart. Our favourite route is by Rutherglen. Connecting this burgh and

Carthcart, there is a delightful footpath, about a mile and a-half in

length, through the intervening fields. It is one of those old kirk-roads

which, having been in popular use from time immemorial, will, it is hoped,

be long preserved from the encroachments of unscrupulous proprietors, who,

in so many instances, have of late enclosed and obliterated these "old

brown lines of rural liberty." Leaving the west end of Rutherglen by this

road, we proceed towards Cathcart in a south-westerly direction. About a

quarter of a mile out of the town we pass the cottage of "Bauldie Baird,"

a plain one-storeyed edifice, which—with its proprietor, a plain blunt

man—has attained considerable local celebrity. Honest Bauldie, who is the

subject of a certain wicked song, for many years earned a decent

livelihood by the sale of "curds and cream," "fruits in their season," and

a wee drap of the mountain dew. His edibles and liqueurs, though of a

homely description, were always excellent in quality; and the place became

a favourite resort of the lads and lasses of Glasgow, who, after the toils

of the week, might have been seen

during the summer and autumn months, in laughing groups in the garden,

enjoying the good cheer which the place afforded. Bauldie had virtuous

neighbours, however, who were determined that there should "be no more

cakes and ale." Complaints were made by these parties that the stringency

of Sabbath rule was occasionally violated on his premises, and ultimately,

on the faith of their representations, the licensing court put their veto

on his trade as a publican. This at once extinguished poor Bauldie’s

popularity. His curds might be as agreeable to the palate as ever, his "grozats"

as large and as well-flavoured, but everybody knows that such dainties are

rendered much more easy of digestion when they are accompanied by a

caulker of the Glenlivet. This necessary addition to the treat Bauldie

having been by law forbidden to dispense, the result was that in a short

time he found his occupation in a great measure gone, his garden an

unpeopled wilderness, and himself a standing jest for triumphant

teetotallers.

At a short distance beyond the

cottage of Bauldie Baird, the road passes over the "Hundred-acre hill," a

beautiful eminence, which commands a series of delightful views of the

surrounding country. On the one hand are undulating fields, in a high

state of cultivation, interspersed with gentlemen’s seats, comfortable

farm-steadings, and picturesque clumps of trees, with Dychmont and the

Cathkin braes in the distance; on the other is a wall of moderate height,

which serves as a screen to shield from withering blasts a lengthened

strip of verdure at its base, which is brightened with the varied hues of

many of our sweetest indigenous plants. Among these we observe the

handsome yellow goat’s-beard, the sweet little field forget-me-not,

the silver-weed the perforated St. John’s-wort

intermingled with clusters of speedwell,

crosswort, and bird’s-foot trefoil, forming altogether

as lovely a fringe to the brown footpath

as poet’s eye could wish to scan. Here, too, we find the first rose of

summer,

"Sweet blooming alone,"

amid countless kindred

buds, on the eve of bursting into light, with their tribute of perfume for

the wandering winds. What sad work the majority of our poets have made

with the appointed times of the flowers! The rose is exclusively a summer

flower, seldom blooming in Scotland before the second week of June. Yet

how frequently do we see in rhyme the spring months decorated with the

"queen of flowers!" Not to talk of minor bards, we find Burns falling into

this error; and Thomson, the minstrel of "the Seasons," one of our best

descriptive poets, invokes the spring in the following fashion:—

"Come, gentle Spring,

ethereal mildness, come,

And from the bosom of you drooping cloud,

while music wakes around, veil’d in a shower

Of shadowing rose; on our plains descend."

When the masters of the lyre are

thus out of joint with the seasons, we need hardly be surprised that with

bards of low degree the "confusion becomes worse confounded," so that were

the mirror held up to nature, it would be utterly impossible, we opine,

for the goddess to recognize her own features. Shakspeare, that mental

triton among the minnows of poetry, is never found thus tripping. Deeply

as he must have studied the world within, he had, at the same time, an

attentive and loving eye for the minutest of external existences. He knew

the season

"when daisies pled and violets blue,

And lady’s smocks all silver white,

And cuckoo buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight;"

and he could tell, with an exactness

as to time that would have pleased even a Linnaeus,

"Of daffodils that come before the

swallow dares,

And take the wings of March with beauty,"

On attaining the southern brow of the bill over which

we have been walking, a landscape of the most exquisite description bursts

upon the view. At the feet of the spectator, and situated at the bottom of

a vast green basin, formed by a girdle of gentle eminences, is the elegant

church of Cathcart, standing in its field of graves, and surrounded by

stately and time-honoured trees. A little beyond is the village of Old

Cathcart, half embowered in dark-green foliage, through which the blue

smoke is gracefully ascending, with that peculiar effect which is so

pleasing to the eye of the painter, and which so frequently tempts his

pencil to imitation. To the right is the battlefield of Langside; to the

left Cathcart Castle, half hidden among woods, and the "Court Knowe," from

which Mary saw her kingdom and crown dashed at one fell swoop for ever

from her grasp. It is indeed a lovely, and from its associations a deeply

interesting scene. For, as the author of the "Clyde" beautifully says,—

"Here, when the moon rides dimly through the sky,

The peasant sees broad dancing standards fly;

And one bright female form, with sword and crown,

Still grieves to view her banners beaten down."

The fine woods and pleasure-grounds of Aikenhead in the

vicinity, also contribute considerably to the beauty of the landscape as

seen from this point.

After lingering here for some time, we take our way

down hill, towards the church. This edifice, which was erected in 1831, on

the site of an old barnlike structure which we well remember, is an

elegant building in the modern Gothic style of architecture. It is

surrounded by a fine burial-ground, quiet and secluded, where beneath the

flickering shadows of several umbrageous old ash trees "the rude

forefathers of the hamlet sleep." The pensive rambler may here spend a

profitable hour, as many a time and oft in bygone days we have, in

meditation among the tombs. Many of the headstones are well worthy the

attention of those who love to study the doleful literature of the dead.

Among the more remarkable of these is one that marks the grave wherein are

interred the ashes of three individuals, who suffered a violent death for

their adherence to the principles of the Solemn League and Covenant, in

the days when Claverhouse and his troopers rode rough-shod over the

consciences of tin Scottish people. Many years ago we remember enacting

"Old Mortality" on this stone, by removing with our gully the moss which

had crept over it and almost obliterated the inscription. Since then a

fresh application of the chisel has rendered it perfectly legible, so that

we should have had no difficulty in transcribing it for our readers,

although it had been effaced from our memory—which, however, from the

strong impression it made on our youthful imagination, it has not. It is

as follows:—

"This is the stone tomb of Robert Thom, Thomas Cook,

and John Urie, martyrs for ouning the covenanted work of Reformation the

11th of May, 1685.

"The bloody murderers of these men

Were Major Balfour and Captain Maitland;

With them others were not frie,

Caused them to search in Polmadle.

As soon as they had them out found

They murthered them with shots of guns;

scarce time did they to them allow

Before their Maker their knees to bow.

Many like in this land have been

Whose blood for wingeance cries to Heaven.

This cruel wickedness yow see

Was done in lon of Polmadie.

This shall a standing witness be

‘Twixt Presbytrie and Prelacie."

The circumstances of this tragedy are found briefly

detailed in Wodrow’s history. The martyrs were men of low degree, poor

weavers and labourers. They resided in the village of Little Govan (now

removed), and they were dragged from their cottages by the dragoons, and

murdered in the immediate vicinity. The scene of their death is directly

opposite the Fleshers’ Haugh of Glasgow Green. In another part of the

ground is a curiously carved old headstone, thickly encrusted with moss

and lichens, yet in a tolerable state of preservation. At each side of the

base is a well-executed sphinx. Immediately above these are a group

representing the Saviour, with a balance and scales in his hand, trampling

on Death, from whose grizzly form springs a tree emblematic of Life. At

the side of the skeleton is a falling figure of Time, with sand-glass and

scythe, while before and behind the Saviour is the winged form of an

angel. On the reverse side of the stone is the following brief inscription

:—

"Here lies the corps of Francis Murdoch, Dean of Guild

of Ayr, who died March 17th, 1722. Ætatis 53.

We learn from tradition that Francis Murdoch was

drowned in the Cart, while on his way from Glasgow to Ayr. The river was

then crossed by a ford, and a spate prevailing at the time, the

unfortunate gentleman was carried away by the angry current, and thus

perished.

Church-yard poetry is seldom worth the perusal—the

simple green mound, without a line to tell whose dust is mouldering below,

making a more eloquent appeal to the heart than the most elaborately

sculptured monument or the most high-sounding epitaph. Yet we must say,

that when, having with some difficulty brushed aside the long rank grass,

we read the following lines, we felt a thrill as if a voice from the lowly

mansion at our feet were whispering the words in our shrinking ear. The

inscriptions are on a couple of flat stones lying side by side, and

covering the ashes of several generations of a family named Hall, who

resided when in life at Cathcart Mill. On the one stone, dated 1689, is

inscribed:-

"Time’s rapid stream we think does stand,

While on it we’re blown down

To a vast sea, which knows no land,

Nor e’er a shore would own;

In which we shall forever swim,

Blest through eternity;

Or sink below wrath’s dreadful stream,

In deepest misery."

On the other, which bears date of 1782, the following is traced:

"A foe death is not to the just and good,

Though he appear to use porter rude;

But faithful messenger and friendly hand

To waft us safely to Immanuel’s land;

There, with pure untold pleasure to behold,

The Joys of heaven and brightness of our Lord,

To which none entered in these fields of bliss

But by the gate alone of righteousness,

Not of our own indeed, but of another—

The anointed Christ, our friend and elder brother."

"O Meliboce! Deus nobis hæc otia fecit— Virgil.

"O Meilbocus! a God gives us this tranquillity."

A chaste little gothic structure has recently been

erected in one corner of the ground by Mr. Gordon of Aikenhead, one of the

principal proprietors in the parish, as a family burying-place. This, as

well as many of the other "sermons in stone" of an humbler description,

will be found worthy of leisurely and thoughtful inspection. [The" Adam

malt" of Lockhart’s powerful tale was minister of this and steeps in the

auld kirk-yard. The real name Is not given in the tale, but the incidents

are in the main strictly true.]

Leaving the kirk-yard, and passing a handsome school,

which, with the manse, is in the immediate vicinity—the latter, like most

other edifices of a similar description, being a very pleasant

habitation—we soon find ourselves on the banks of the murmuring Cart. The

stream in this vicinity winds its seaward way through banks of great

beauty, thickly wooded, and, above the village, of considerable altitude.

We observe the sand-piper, the sand-martin, and the elegant gray wagtail

playing about the margin of the waters, while among the foliage which

overshadows their rippled breast is heard the music of many birds. Not the

least sweet is the wail of the yellowhammer, which at once, in association

with the surrounding scenery, recalls to our mind the memory of a poet who

in other days rambled a happy boy on this very bank. We allude to Grahame,

the author of the "Sabbath," who in his youth lived for some time in this

vicinity. In the "Birds of Scotland "—a production of his genius which has

always been an especial favourite of ours, although it has never attained

anything like an extensive popularity—he gives a description of the first

bird’s nest which he ever discovered. The nest was that of a yellowhammer,

one of our loveliest though most common songsters, and the scene was the

banks of Cart, a short distance below the manse. The passage, which to our

mind seems an exceedingly fine bit of word-painting, is as follows:—

"I love thee, pretty bird! for ‘twas thy nest

Which first, unhelped by older eyes, I found.

The very spot I think I now behold!

Forth from my low-roofed home I wandered blythe,

Down to thy side, sweet Cart, where ‘cross the stream

A range of stones, below a shallow ford,

Stood in the place of the now spanning arch;

Up from that ford a little bank there was,

With alder copes and willow overgrown,

Now worn away by mining winter floods;

There, at a bramble root, sunk in the grass,

The hidden prize, of withered field-straws formed,

Well lined with many a coil of hair and moss,

And in it laid five red—veined spheres, I found.

The Syracusan’s voice did not exclaim

The grand Eureka with more rapturous joy

Than at that moment fluttered round my breast."

The author of the "Pleasures of Hope," who like Grahame

was a Glasgow callant, also spent some of his happiest youthful days at

Cathcart. During vacations he was a frequent visitor and an occasional

resident for weeks together at the manse. Nor, indeed, do we know a spot

where the fancy of a poet could have been more fitly nursed The banks of

the river and the surrounding country are rich in varied beauty. The

gently swelling hill or the verdant mead—the shadowy wood where the cushat

loves to dwell, or the leafy lane where the shilfa builds his nest—the

dashing waterfall, or the torrent rippling through wild and bosky banks—in

short, all the choicest features of landscape, are congregated in the

vicinity; while the silent church-yard, the old castle, and the

battle-field of Langside, lend to natural beauty the deeper charm of

sentimental association. There can be no doubt that much of the fine

imagery with which the poet afterwards adorned the productions of his

heart-touching lyre, were gleaned by the wandering schoolboy from the

green banks of Cart. After the lapse of many years, during which he had

achieved a name among men, and mingled with the loftiest in the land,

Campbell came once more to gaze upon the scenery, which,

"In life’s morning march, when his bosom was young,"

he had so rapturously enjoyed. He came to experience

the disappointment which all must feel who, dreaming not of time and

change, return to the haunts of other days. The old familiar faces had

departed, and seen in the gloom of sorrow, the landscape seemed less fair,

and the very flowers less brilliant than in days o’ langsyne. He penned

the following lines as an expression of his feelings, and left the place

to return no more:—

"Oh, the scenes of my childhood and dear to my heart,

Ye green waving woods on the margin of Cart;

Bow bleat in the morning of life I have strayed

By the stream of the vale and the grass-covered glade !

"Then, then, every rapture was young and sincere,

Ere the sunshine of bliss was bedimmed with a tear,

And a sweeter delight every scene seemed to lend,

That the mansion of peace was the home of a friend,

"Now, the scones of my childhood and dear to my heart,

All pensive I visit, and sigh to depart;

Their flowers seem to languish, their beauty to cease,

For a stranger inhabits the mansion of peace.

"But hush’d be the sigh that untimely complains,

While friendship and all its endearments remains,

While it blooms like the flower of a winterless clime,

Untainted by change, unabated by time."

However it might seem to the tear-dimmed eye of the

poet, leaf and flower are as abundant and as beautiful around Cathcart now

as ever they were in the past. We can assure the youthful botanist that he

will find the steep banks at and immediately above the bridge, peculiarly

rich in the material of his study. Any one who has ever glanced into

Hooker’s Flora Scotica (the habitats given in which, we may remark,

are the best of all indices to the beautiful in Scotland that we know),

must have observed numerous references to localities in this

neighbourhood.

The village of Old Cathcart is somewhat irregular and

scattered. It consists of some score or so of houses, mostly one-storeyed,

and with little patches of garden-ground attached to them. Among these are

a handsome farm-steading, a smithy or cartwright establishment, a

snuff-mill, and in the neighbourhood an extensive paper manufactory. It

has two public-houses, one of which, that of Mr. Mitchell, is an

exceedingly neat and comfortable little place of rest and refreshment. The

landlord is an amateur florist, and his small garden plot, with its

flower-beds and bee-hives, is a perfect model of neatness and beauty. It

seems, moreover, to be a favourite haunt of ramblers from the city, who,

with "all the comforts of the Sautmarket," find besides the charms of

rural beauty and quietude in its leafy bowers.

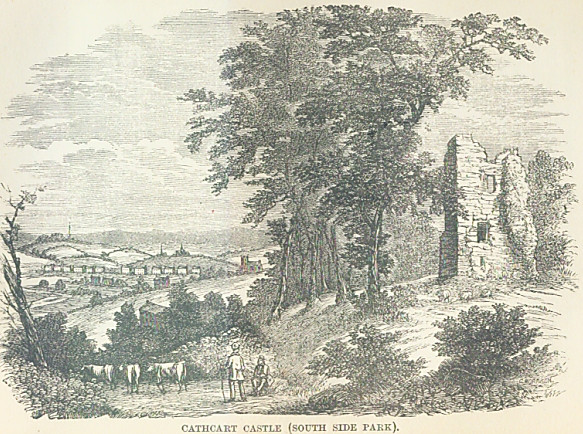

A short distance above the village, on a steep bank

which rises over the Cart, are the ruins of the castle, which we next

proceed to visit. This structure, a massy square tower, must at one period

have possessed great value as a place of security and strength. The date

of its erection and the name of its builder are alike lost in a dark

antiquity. In the days of Wallace and Bruce it was in the possession of an

Alan de Cathcart, who did good service in, the cause of Scottish

independence. From this individual the present Earl of Cathcart is

lineally descended. About the middle of the sixteenth century, the barony

and castle of Cathcart were sold by the then possessor to the Lord of

Sempil, from whose family it was transferred to the Blairs of Boghen. In

1801 it was purchased by the late Earl of Cathcart, whose son, the present

earl, is now its proprietor. On examining the castle, we find it to be one

of those stubborn fragments of the past which seem destined to bid an

enduring defiance alike to the war of the elements and of time. By the

measurement of our stag we find its walls to be not less than ten feet in

solid thickness. It is now roofless and chamberless, with the exception of

a vault, wherein darkness is rendered visible by the light which enters at

a narrow loophole. Here, probably, in "the good old times" when the law of

the land was the caprice of a lordling, the unhappy serfs who happened to

displease their feudal superior were kept secure until it might be found

convenient to dispose of them otherwise. This place has a damp

charnel-house smell, which speedily sends us into the sunshine again. The

crumbling tower is in some parts thickly mantled with ivy, the haunt of

the starling and sparrow, while the swift builds its nest and the

wall-flower waves its golden flowers in the loop-holes and window-places.

From the castle there is a fine view of the vale of the Cart, with the

modern mansion of the family in the foreground, and a perfect wilderness

of foliage around and beyond. There are, indeed, some exquisite snatches

of landscape in this vicinity, and we would recommend the locality

altogether to the special attention of our Glasgow artists, who, like

others, are too apt to run from home in their pursuit of the beautiful.

About a hundred yards or so east from the castle is the

"Court Knowe," where Queen Mary stood at the most critical moment of her

life. A thorn-tree which threw its shadow over her, and was long called by

her name, grew on the spot until the close of the last century, when it

fell into decay through age. An upright slab of stone, with a rude carving

of the Scottish crown, and the letters "M.R. 1568," now mark the spot.

This interesting memento of the beauteous being who in a past age ascended

to its site—a queen with thousands of gallant men at her command—and in

one little hour thereafter descended from it a hapless fugitive, has been

appropriately shaded by a fine clump of trees. We find the speedwell, the

king-cup, and the forget-me-not blooming in beauty on the velvet turf that

had been dewed with the tears of royalty, and the emblematic

-

"Pansy that looks up

Like a thought earth-planted."

It is indeed a lovely and a fitting place to muse on

that fair, ill-fated woman, whose memory is inseparably linked to so many

beauteous scenes, and whose story must ever touch the deepest sympathies

of the pensive heart. The evening sun is bathing the landscape in mellow

radiance while we linger, and the wild birds are singing their vespers as

if misfortune and sorrow had never flung their shadows there; but the

winds are murmuring a plaintive melody among the trembling leaves, and

showering around us the fine gold of the laburnum, which is now becoming

dim, as if nature, entering into our feelings, meant to show the

evanescence of earthly glory. The landscape seen from this station is

extensive and beautiful, including, as is well known, an excellent

prospect of the battle-field of Lang-side. The blue smoke of Cathcart is

seen close at hand curling through the trees; beyond is the church and the

shadowy burying-place; and in the distance the spires of Glasgow, relieved

against the towering Kilpatrick hills.

Descending from our elevation, we cross the Cart by the

old bridge, a structure which bears a considerable resemblance to the Brig

o’ Doon, and on the sides of which the botanist will find several

beautiful though minute species of ferns. We then take our way to New

Cathcart, a neat and tidy-looking little village, which lies about the

third of a mile to the west. It is of modern origin, and possesses but few

features of interest. From thence, along a pleasant country road, we pass

by Millbrae to Langside. This little hamlet, which has been rendered

remarkable by the decisive skirmish which occurred in its vicinity between

the troops of Queen Mary and those of the Regent Murray, on the 18th of

May, 1568, is finely situated nearly on the ridge of a long hill which

lies at a little distance to the south-west of Glasgow. The story of the

battle, with its antecedents and ultimate consequences, is familiar to

every student of Scottish history. Queen Mary on her escape from Lochleven,

immediately, with the assistance of her friends, many of whom were

possessed of great influence, proceeded to organize an army for the

recovery of that power which, while in captivity, she had been compelled

formally to renounce. In a short period she found herself at the head of a

considerable body of troops. With these she was on her march from Hamilton

to Dumbarton, when she found herself intercepted by the vigilant and

energetic Regent, who having heard of her advance, pushed out from Glasgow

with all the forces he could command, and took up a favourable position at

the village of Langside. With greater bravery than prudence Mary’s party

resolved to risk an engagement; and while she proceeded to the position we

have previously described, her troops at once formed themselves into order

of battle on the north side of Clincart Hill, a gentle eminence adjoining

that on which their opponents were drawn up in battle array. Impatient of

delay, the inexperienced infantry of the Queen rushed up the hill to the

attack, but from the unfavourable nature of the ground, and the superior

numbers and discipline of the Regent’s troops, after a brief but

sanguinary struggle, they were repulsed, and by a decisive charge of

cavalry, which was skilfully directed against their flank at a critical

moment, they were involved in inextricable confusion, and ultimately put

to complete rout. Nearly three hundred of the Royalists, it is stated,

fell on the field of battle, while four hundred were made prisoners. The

loss of the Regent was trifling in the extreme. On returning to the city

he caused thanks to be publicly offered to the Deity for a victory

which, on his side, was almost bloodless; and he rewarded the Corporation

of Bakers, who had particularly distinguished themselves by their bravery

on the occasion, by bestowing on them the lands of Partick, where their

mills are now built. Poor Mary, on seeing the overthrow of her friends,

took to flight, and, it is said, scarcely closed an eye until she arrived

at Dundrennan Abbey in Galloway, nearly sixty miles from the fatal scene.

By what route she arrived there we cannot now tell, but several spots in

our vicinity are pointed out by tradition as marking the way she took.

Between Cathcart and Rutherglen is a place called "Mel’s Mire," where it

is said her horse almost stuck fast, in consequence of the muddy nature of

the soil. On the same line, but nearer Rutherglen, is a place called the "Fants,"

it is said from the panting which her steed made while hurrying past. A

little to the east of this, at a place called "Din’s Dykes," two fellows

who were cutting hay lifted their scythes and threatened to take her

captive. Some of her friends coming up, however, compelled the haymakers

to clear the way, when she passed on; and we next hear of her in a

Cambuslang tradition, crossing the Clyde a little below Carmyle, at a

place called the "Thief's Ford." Here we lose sight of her until, weary

and worn, at the close of the day, she is found at Dundrennan, where a

rhyming friend of our’s puts the following words of lamentation into her

lips, which, as appropriate to the occasion, and hitherto unpublished, we

shall present to our readers:—

"Loud roars the wind adown the

shaw,

The drumlie clouds are big wi’ rain,

Fast hameward flees the frichten’d craw,

The sea-bird, screaming, leaves the main;

Sae I, before misfortune’s gale,

A waefu’ wanderer now mann flee—

An exile sad free ll I love,

Despair alone remains with me.

"Thou sun, red sinking down the west,

Oh, haste thee, close the hateful day

With ruin fraught, and stained with gore

Of noblest hearts—my pride and stay.

Triumphant treason’s banner floats

O’er purpled Cartha’s devious way,

Where hearts that heaved yestreen wi hope

Lie cauld sad lifeless in the day.

"O God! how bitter is the cup

Thy chastening hand has filled for me—

How crushing is the weird of wrath

That I, a worm of earth, mann dree!

My country false, my babe estranged,

My name the butt of calumny;

Even hope—the wretch’s friend—takes wing,

Nor dares to mock my agony.

"Vain pomp and grandeur of the world,

How false to me your pleasures seem!

Like drewdrope melting in the sun,

Or bubbles on the mountain stream.

Now, I maun bid farewell to pride,

And I maim stoop—oh, thought of woe!—

This aching, crownless, homeless head,

A suppliant to my direst foe.

"Proud land of hills—my fatherland—

Adieu!—a long, a last adieu!

Despair is whispering to my soul

I ne’er again shall gaze on you.

Oh, when your hapless Mary‘s gone,

May brightest fortune be your fa’ !

Ye’ll haply mourn your wrangs to me,

When I for aye have passed awa’."

But all signs of battle have long been effaced from the

fair brow of Langside; and it is fervently to be hoped that never again

may the soil of our country be stained with the blood of brother fighting

against brother, as on that dark day. The very spirit of peace indeed

seems brooding over the scene as we pass along the pleasant hill. The

farmer is plodding home in the gathering gloaming from the toils of the

day. The soft rustle of the waving grain is making sweet music to the

passing winds, which have been wantoning through the bloom of the bean,

"And bear its fragrant sweets alang."

The lark is leaving the sky, and seeking its mate on

the grassy lea; while the bat comes flickering past, and the bugle of the

"shardborne beetle" is occasionally heard in the thickening air. This walk

is indeed delicious. The prospect is extensive and beautiful. In the

valley beneath, amid richly cultivated fields, the Cart is seen by

glimpses winding its devious way; farther off, and in various directions,

the spires of Glasgow, Rutherglen, and Cambuslang attract the eye of the

spectator; while Cathcart, with its fine church, its picturesque cottages,

and its old castle peeping over the trees, nestles sweetly on the green

slopes below.

The village or hamlet of Langside consists of some

score or so of houses, principally one storeyed cottages, clustering

irregularly amidst patches of garden, and finely screened by fruit and

other trees. Like most other Scottish villages, it seems to have been left

in a great measure to "hing as it grew," and consequently it possesses a

picturesqueness of aspect to which our more regularly constructed modern

towns are utter strangers. The majority of the inhabitants are weavers,

who manage to make ends meet better than the generality of their city

brethren, by the cultivation, during spare hours, of their bits of kail-yard,

the produce of which adds materially to the comfort of their families.

Several of them are famous for the quality of their gooseberries, the

excellence of which during July and August tempts numerous parties from

the neighbouring city. We have not learned that anything beyond the

general tradition regarding the battle, which is common over the country,

has been preserved by the inhabitants of Langside. A neighbouring farmer,

we are informed, has several times discovered old horse-shoes, bits of

bridles, and other relics, while cultivating the fields where the

engagement took place; but beyond these no vestige of "what has been" is

now in existence. [The hill of Langside is in process of being covered by

ornamental cottages and villas. Already the Clincart Knowe is crowned by a

couple of tenements, and even on the very spot where the contest occurred,

a number of houses have been erected. These neat and comfortable looking

domiciles certainly do not harmonize with the associations of the spot;

while a public work, which has just been planted In the basin of the Cart.

still more detracts from the amenity of the picture.]

"All, all Is quiet now, or only heard

Like mellowed murmurs of the distant sea."

A walk of short duration from the field of battle

brings us safely into the artificial day of the lamp-lighted streets.

Three Aikenhead

and Hagthornhill Deeds, 1508-1545

LANGSIDE BATTLEFIELD

MR. WILLIAM GEMMILL, writer, Glasgow, has an

unusually interesting little group of title deeds of lands on the south

side of Glasgow, all originally part of the Aikenhead estate in the

parish of Cathcart. Many reasons make these documents historical.

|