|

The Scottish Gipsies appear

to be extremely tenacious of retaining their language, as their principal

secret, among themselves, and seem, from what I have read on the subject, to

be much less communicative, on this and other matters relative to their

history, than those of England and other countries. On speaking to them of

their speech, they exhibit an extraordinary degree of fear, caution,

reluctance, distrust, and suspicion ; and, rather than give any information

on the subject, will submit to any self-denial. It has been so well retained

among themselves, that I believe it is scarcely credited, even by

individuals of the greatest intelligence, that it exists at all, at the

present day, but as slang, used by common thieves, house-breakers and

beggars, and by those denominated flash and family men.

[Before considering this

trait in the character of the Scottish Gipsies, it may interest the reader

to know that the same peculiarity obtains among those on the continent.

Of the Hungarian Gipsies,

Grellmann writes: "It will be recollected, from the first, how great a

secret they make of their language, and how suspicious they appear when any

person wishes to learn a few words of it. Even if the Gipsy is not perverse,

he is very inattentive, and is consequently likely to answer some other

rather than the true Gipsy word."

Of the Hungarian Gipsies,

Bright says: "No one, who has not had experience, can conceive the

difficulty of gaining intelligible information, from people so rude, upon

the subject of their language. If yon ask for a word, they give you a whole

sentence; and on asking a second time, they give the sentence a totally

different torn, or introduce some figure altogether new. Thus it was with

our Gipsy, who, at length, tired of our questions, prayed most piteously to

be released; which we granted him, only on condition of his returning in the

evening."

Of the Spanish Gipsies, Mr.

Borrow writes: "It is only by listening attentively to the speech of the

Gitanos, whilst discoursing among themselves, that an acquaintance with

their dialect can be formed, and hy seizing upon all unknown words, as they

fall in succession from their lips. Nothing can be more useless and hopeless

than the attempt to obtain possession

of their vocabulary, by

enquiring of them how particular objects and ideas are styled in the same;

for, with the exception of the names of the most common things, they arc

totally incapable, as a Spanish writer has observed, of yielding the

required information; owing to their great ignorance, the shortness of their

memories, or, rather, the state of bewilderment to which their minds are

brought by any question which tends to bring their reasoning faculties into

action; though, not unfrequently, the very words which have been in vain

required of them will, a minute subsequently, proceed inadvertently from

their mouths."

What has been said hy the two

last-named writers is very wide of the mark; Grellmann, however, hits it

exactly. The Gipsies have excellent memories. It is all they have to depend

on. If they had not good memories, how could they, at the present day, speak

a word of their language at all? The difficulty in question is down-right

shuffling, and not a want of memory on the part of the Gipsy. The present

chapter will throw some light on the subject. Even Mr. Borrow himself gives

an ample refutation to his sweeping account of the Spanish Gipsies, in

regard to their language; for, in another part of his work, he says: " I

recited the Apostles' Creed to the Gipsies, sentence by sentence, which they

translated as I proceeded. They exhibited the greatest eagerness and

interest in their unwonted occupation, and frequently broke into loud

disputes as to the best rendering, many being offered at the same time. I

then read the translation aloud, whereupon they raised a shout of

exultation, and appeared not a little proud of the composition." On this

occasion, Mr. Borrow evidently had the Gipsies in the right humour—that is,

off their guard, excited, and much interested in the subject. He says, in

another place: "The language they speak among themselves, and they are

particularly anxious to keep others in ignorance of it." As a general

tiling, they seem to have been bored by people much above them in the scale

of society; with whom, their natural politeness, and expectations of money

or other benefits, would naturally lead them to do anything than give them

that which it is inborn in their nature to keep to themselves.—Ed.

Among the causes contributing

to this state of things among the Scottish Gipsies, and what are called

Tinklers or Tinkers, for they are the same people, may be mentioned the

following: The traditional accounts of the numerous imprisonments,

banishments, and executions, which many of the race underwent, for merely

being "by habit and repute Gipsies," under the severe laws passed against

them, are still fresh in the memories of the present generation. They still

entertain the idea that they are a persecuted race, and liable, if known to

be Gipsies, to all the penalties of the statutes framed for the extirpation

of the whole people. But, apart from this view of the question, it may be

asked, how is it that the Gipsies in Scotland are more reserved, (they are

generally altogether silent,) in respect to themselves, than their brethren

in other countries seem to be? It may be answered, that our Scottish tribes

are, in general, much more civilized, their bands more broken up, and the

individuals more mixed with, and scattered through, the general population

of the country, than the Gipsies of other nations; and it therefore appears

to me that the more their blood gets mixed with that of the ordinary

natives, and the more they approach to civilization, the more determinedly

will they conceal every particular relative to their tribe, to prevent their

neighbours ascertaining their origin and nationality. The slightest taunting

allusion to the forefathers of half-civilized Scottish Tinklers kindles up

in their breasts a storm of wrath and fury : for they are extremely

sensitive to the feeling which is entertained toward their tribe by the

other inhabitants of the country. [This opinion is confirmed by the fact

that the Gipsies whom the Rev. Mr. Crabbe has civilized will not now be seen

among the others of the tribe, at his annual festival, at Southampton. We

have already seen, under the head of Continental Gipsies, that "those who

are gold-washers in Transylvania and the Banat have do intercourse with

others of their nation ; nor do they like to be called Gipsies."] "I have,"

said one of them to me, "wrought all my life in a shop with

fellow-tradesmen, and not one of them ever discovered that I knew a single

Gipsy word." A Gipsy woman also informed me that herself and sister had

nearly lost their lives, on account of their language. The following are the

particulars: The two sisters chanced to be in a public-bouse near Alloa,

when a number of colliers, belonging to the coal-works at Sauchie, were

present. The one sister, in a low tone of voice, and in the Gipsy language,

desired the other, among other things, to make ready some broth for their

repast. The colliers took hold of the two Gipsy words, shaucha and blawkie,

which signify broth and pot; thinking the Tinkler women were calling them

Sauchie BlacJcies, in derision and contempt of their dark, subterraneous

calling. The consequence was, that the savage colliers attacked the innocent

Tinklers, calling out that they would; "grind them to powder," for calling

them Sarichie Blackies. But the determined Gipsies would rather perish than

explain the meaning of the words in English, to appease the enraged

colliers; "for," said they, "it would have exposed our tribe, and made

ourselves odious to the world." The two defenceless females might have been

murdered by their brutal assailants, had not the master of the house

fortunately come to their assistance. The poor Gipsies felt the effects of

the beating they had received, for many months thereafter; and my informant

had not recovered from her bruises at the time she mentioned the

circumstances to me. [On the whole, however, our Scottish peasantry, in some

districts, do not greatly despise the Tinklers; at least not to the same

extent as the inhabitants of some other countries seem to do. When not

involved in quarrels with the Gipsies, our country people, with the

exception of a considerable portion of the land-owners, were, and are even

yet rather fond of the superior families of the nomadic class of these

people, than otherwise.]

They are also anxious to

retain their language, as a secret among themselves, for the use which it is

to them in conducting business in markets or other places of public resort.

But they are very chary of the manner in which they employ it on such

occasions. Besides this, they display all the pride and vanity in possessing

the language which is common with linguists generally. The determined and

uniform principle laid down by them, to avoid all communications with "

strangers" on the subject, and their resolution to keep it a secret within

their own tribe, will be strikingly illustrated by the following facts.

For seven years, a woman, of

the name of Baillie, about fifty years of age, and the mother of a family,

called regularly at my house, twice a year, while on her peregrinations

through the country, selling spoons and other articles made from horn. Every

time I saw her, I endeavoured to prevail upon her to give me some of her

secret speech, as I was certain she was acquainted with the Gipsy tongue.

But, not to alarm her by calling it by that name, I always said to her, in a

jocular manner, that it was the mason word I wished her to teach me. She,

however, as regularly and firmly declared that she knew of no such language

among the Tinklers. I always treated her kindly, and desired her to continue

her visits. I gave her, each time she called, a glass of spirits, a piece of

flesh, and such articles; and generally purchased some trifle from her, for

which I intentionally paid her more than its value. She so far yielded to my

importunities, that, for the last three years she called, she went the

length of saying that she would tell me "something" the next time she came

back. But when she returned, she guardedly evaded all my questions, by

constantly repeating nearly the same answer, such as, "I will speak to you

the next time I come back, sir." After having been put off for seven years

in this manner, I was determined to put her to the usual test, should she

never enter my door again, and, as she was walking out of the gate of my

garden, I called to her, in the Gipsy language, "Jaw vree, managie!"—(go

away, woman.) She immediately turned round, and, laughing, replied, "I will

jaiv with you when I come back, gaugie"—(I will go or speak with you, when I

come back, mau.) She returned, as usual, in December following. I again

requested her to give me some of her words, assuring her that she would be

in no danger from me on that account. I further told her it was of no use to

conceal her speech from me, having, the last time she was in my house, shown

her that I was acquainted with it. After considerable hesitation and

reluctance, she consented ; but then, she said, she would not allow any one

in the house to hear her speak to me but my wife. I took her at once into my

parlour, and, on being desired, she, without the least hesitation or

embarrassment, took the seat next the fire. Observing the door of the room a

little open, she desired it to be shut, for fear of her being overheard,

again mentioning that she had no objections to my wife being present, aud

gravely observing that "husbands and wives were one, and should know all one

another's secrets." She stated that the public would look upon her with

horror and contempt, were it known she could speak the Gipsy language. She

was extremely civil and intelligent, yet placed me upon a familiar equality

with herself, when she "found I knew of the existence of her speech, and

could repeat some of the words of it. Her nature, to appearance, seemed

changed. Her bold and fiery disposition was softened and subdued. She was

very frank and polite; retained her self-possession, and spoke with great

propriety. [Their (the female's) speech is as fluent, and their eyes as

unabashed, in the presence of royalty, as before those from whom they have

nothing to hope or fear; the result of which is, that most minds quail

before them.—Biyrrow on the Spanish Gipsies.—Ed.] The words which I got on

this occasion will be found in another part of the chapter.

In corroboration of this

principle of concealment observed by the Scottish Gipsies, relative to their

language, I may give a fact which will show how artful they are in avoiding

any allusion to it. One evening, as a band of potters, with a cart of

earthenware, were travelling on the high-road, in a wild glen in the south

of Scotland, a brother of mine overheard them, male and female, conversing

in a language, a word of which he did not understand. As the road was very

bad, and the night dark, one of the females of the band was a few yards in

advance of the cart, acting as a guide to the horde. Every now and then,

among other unintelligible expressions, she called out " Shan drown." My

brother's curiosity was excited by hearing the potters conversing in this

manner, and, next morning, he went to where they lodged, in an out-house on

the farm, and enquired of the female what she was saying on the road, the

night before, and what she meant by "Shan drom." The woman appeared confused

at the unexpected question; but in a short time recovered her

self-possession, and artfully replied that they were talking Latin (!) and

that "Shan drom," in Latin, signified "bad road." But the truth is, "Shan

drom" is the Gipsy expression for bad road, as will by and by be seen.

Besides the difficulties

mentioned in the way of getting any of their language from them, there is a

general one that arises from the suspicious, unsettled, restless, fickle and

volatile nature by which they are characterized. It is a rare thing to get

them to speak consecutively for more than a few minutes on any subject, thus

precluding the possibility, in most instances, of taking advantage of any

favourable humour in which they may be found, in the matter of their general

history—leaving alone the formal and serious procedure necessary to be

followed in regard to their language. If this favourable turn in their

disposition is allowed to pass, it is rarely anything of that nature can be

got from them at that meeting; and it is extremely likely that, at any after

interviews, they will entirely evade the matter so much desired.

With these remarks, I will

now proceed to state the method I adopted to get at the Gipsy language.

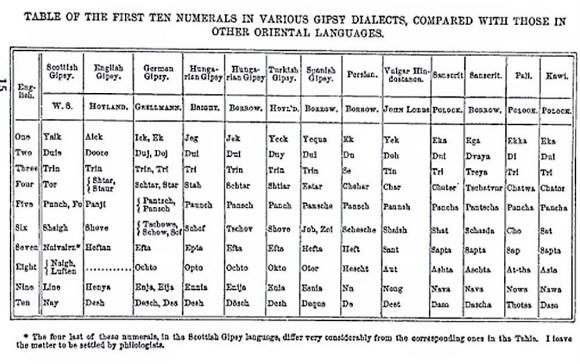

Short vocabularies of the

language of the Tsohengenes of Turkey, the Gyganis of Hungary, the Zigeimers

of Germany, the Gitanos of Spain, and the Gipsies of England, have, at

different periods, since 1783, issued from the press, in this country and in

Germany; but I am not aware of any specimens of our Scottish Tinkler or

Gipsy language having as yet been submitted to the public. Some of the

former I committed to memory, and used, intermixed with English words, in

questions I would put to the Scottish Gipsies. In this way, one word would

lead to another. I would address them in a confident and familiar manner, as

if I were one of themselves, and knew exactly who they were, and all about

them. I would, for instance, ask them Have you a grye (horse)?

How many chauvies (children) have you? Where is your gaugie

(husband)? Do you sell roys (spoons)? Being taken completely by

surprise, they would give me at once a true answer. For, being the first, as

far as I know, to apply the language of the Gipsies of the continent to our

own tribes, they could naturally have no hesitation in replying to my

questions; although they would wonder what kind of a Gipsy I could possibly

be—dressed, as I was, in black, with black neck-cloth, and no display of

linen, save a ruffled breast, thick-soled shoes and gaiters. The consequence

was, I became a character of interest to many of the Gipsies to be found in

a circuit of many miles; and great wonder was excited in their untutored

minds, leading to a desire to see, and know something of, the Riah Nawken,

or the gentleman Gipsy. On such occasions, I would treat them as I would

land a fish—give them hook and line enough. But the circumstance was to them

something incomprehensible, for, although Gipsies are very ready-witted, and

possess great natural resources, in thieving, and playing tricks of every

kind, and great tact in getting out of difficulties of that nature—which,

with them, are matters of instinct, training, and practice—their whole mind

being bent, and exclusively employed, in that direction, it was almost

impossible for them to form any intelligible opinion as to my true

character, provided I was any way discreet in disguising my real position

among them. As little chance was there of any of themselves informing the

others of what assistance they had inadvertently been to me, in getting at

their language. Some of them might have an idea that one of their race had,

in their own way of thinking, peached, turned traitor to their blood, and

let the cat out of the bag. At times, if they happened to see me approach

them, so as to have an opportunity to scrutinize me—which they are much

given to, with people generally—they would not be so easily disconcerted at

any question put to them in their language; but the result would be either

direct replies, or the most ludicrous scenes of surprise and terror

imaginable, which, to be enjoyed, were only to be seen, but could not be

described, although the sequel will in some measure illustrate them. At

other times, if I addressed a Gipsy in his own language, and spoke to him in

a kind and familiar manner, as if I had been soothing a wild and

unmanageable horse, before mounting him, he would either very awkwardly

pretend not to understand what I meant, or, with a downcast and guilty look,

and subdued voice, immediately answer my Gipsy words in English. But if I

put the words to him in an abrupt, hasty, or threatening manner, he would

either use his heels, or turn upon me, like a tiger, and pour out upon me a

torrent of abusive language. The following instances will show the manner in

which my use of their language was sometimes appreciated by the female

Gipsies.

When I spoke in a sharp

manner to some of the old women, on the high-road, by way of testing them,

they would quicken their paces, look over their shoulders, and call out, in

much bitterness of spirit, "You are no gentleman, sir, otherwise you would

not insult ns in that way." On one occasion. I observed a woman with her

son, who appeared about twelve years of age, lingering near a house at which

they had no business, and I desired her, rather sharply, to leave the place,

telling her that I was afraid her chauvie was a chor—(that her son was a

thief). I used these two words merely to see what effect they would have

upon her, as I did not really think she was a Gipsy. She instantly flew into

a dreadful passion, telling me that I had been among thieves and robbers

myself, otherwise I could not speak to her in such words as these. She

threatened to go to Edinburgh, to inform the police that I was the head and

captain of a band of thieves, and that she would have me immediately

apprehended as such. Four sailors who were present with me were astonished

at the sudden wrath and insolence of the woman, as they could not perceive

any provocation she had received from me—being ignorant of the meaning of

the words chauvie and clwr, which I applied to her boy.

One day I fell in by chance,

on a lonely part of the old public road, on the hills within half a mile of

the village of North Queensferry, with a woman of about twenty-seven years

of age, and the mother, as she said, of seven children.

She had light hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. The

youngest of her children appeared to be about nine months old, and the

eldest about ten years. The mother was dressed in a brown cloak, and the

group had altogether a very squalid appearance. In the most lamentable tone

of voice, she informed me that her husband had set off with another woman,

and left her and her seven children to starve ; and that he had been lately

employed at a paper-mill in Mid-Lothian. She sometimes appeared almost to

choke with grief, but, nevertheless, I observed no tears in her eyes. She

often repeated, in a sort of hypocritical and canting manner, "The Lord has

been very kind to me, and will still protect me and my helpless babes. Last

night we all slept in the open fields, and gathered peas and beans from the

stubble for our suppers." . She certainly seemed to be in very indigent

circumstances; but that her husband had abandoned her, I did not credit.

However, I gave her a few half-penee, for which she thanked me very civilly.

Prom her extravagant behaviour, and a peculiar wildness in her looks, it

occurred to me that she belonged to the lowest caste of Gipsies, although

her appearance did not indicate it; that her grief was, for the most part,

feigned, and that the story of her husband having abandoned her was got up

merely to excite pity, for the purpose of procuring a little money for the

subsistence of her band. I now put a number of questions to her, relative to

many individuals whom I knew were Gipsies of a superior class, taking care

not to call them by that name, for fear of alarming her. I spoke to her as

if I had been quite intimate with all the persons I was enquiring about. She

gave me satisfactory answers to almost every question, and seemed well

acquainted with every individual I named. She now appeared quite calm and

collected, and answered me very gravely. But she said that some of the men I

mentioned were rogues, and that their wives played many clever tricks. On

mentioning the tricks of the wives, I noticed a smile come over her

countenance. I observed to her that they were not faultless, but that they

were often blamed for crimes of which they were not guilty. Upon perceiving

that I took their part, which I did on purpose, to hear what she would say,

she gradually changed her mind, and came over to my opinion. She said that

they were exceedingly good-hearted people, and that some of them had

frequently paid a night's lodging for herself and family. I

now ventured to put a question to her, half in Gipsy and half in English.

After a short pause and hesitation, she signified that she understood what I

said. I then asked one or two questions in Gipsy words only. A Gipsy, with

crockery-ware in a basket, happened to pass ns at the very moment I was

speaking to her; and to show her the knowledge I had of her speech and

people, I said, "There is a natvhen"—(there is a Gipsy.) She, in a

very civil and polite manner, immediately replied, "Sir, I hope you will not

take it ill, when I use the freedom of saying that you must have been among

the people you are enquiring about, otherwise you could not speak to me in

that way." To show her that I did not despise her for understanding my Gipsy

words, I gave her a few pence more, and spoke kindly to her. She then became

quite cheerful and frank, as if we had been old acquaintances. Instead of

trying to impose upon me, by tales of grief and woe, and feigned

piety, she appeared happy and contented, her whole conduct indicating that

it was useless to play off her tricks upon me, as she was now sensible that

I knew exactly what she was, and yet did not treat her contemptuously. She

said her husband's name was Wilson, and her own Jackson, (the names of two

Gipsy tribes ;) that she could tell fortunes, and was acquainted with the

Irish words I spoke, being afraid to call them by their right name. She

further stated that every one of the people I was enquiring about spoke in

the same language.

About half an hour after I parted with her, on the road,

I met her in the village of North Queensferry, while I was walking with a

friend. I then put a question to her in Gipsy words, in the presence of this

third party, who knew not what she was, to see how she would conduct herself

in public. She seemed surprised at my question, as if she did not understand

a word of it—to prevent it being discovered to others of the community that

she was a Gipsy. But she publicly praised me highly, for having given her

something to help her poor children ; and, with her trumped-up story at her

tongue's end, proceeded on her travels.

These poor people were much alarmed when I let them see

that I knew they were Gipsies. They thought I was despising them, and

treating them with contempt; or they were afraid of being apprehended under

the old sanguinary laws, condemning the whole unfortunate race to death; for

the Gipsies, as I have already said, still believe that these bloody

statutes are in full force against them at the present day.

I was advised by Sir "Walter Scott, as mentioned in the

Introduction, to "get the same words from different individuals; and, to

verify the collection, to set down the names of the persons by whom they

were communicated;" which I have done. For this reason, the words now

furnished will appear as the confessions of so many individuals, rather than

a vocabulary drawn up in the manner in which such is usually done; and which

will be more satisfactory to the general reader, as well as the philologist,

than if I had presented the words by themselves, without any positive or

circumstantial evidence of their genuineness. To the general reader, as

distinguished from the philologist, the anecdotes connected with the

collection may prove interesting, if the words themselves have no attraction

for him; while they will satisfy the latter, as far as they go, as to the

existence of a language which has almost always been denied, yet which is

known, at the present day, to a greater number of the population of the

country than could at first have been imagined; this part of it having been

drawn from a variety of individuals, at different and widely-separated times

and places. On this account, I hope that the minuteness of the details of

the present enquiry may not appear tedious, but, on the contrary,

interesting, to my readers generally ; inasmuch as the present collection is

the first, as far as I know, of the Scottish Gipsy language that has ever

been made ; although the people themselves have lived amongst us for three

hundred and fifty years, and talked it every hour of the day, but hardly

ever in the hearing of the other inhabitants, excepting, occasionally, a

word of it now and then, to disguise their discourse from those around them

; which, on being questioned, they have always passed off for cant,

to prevent the law taking hold of them, and punishing them for being

Gipsies. These details will also show that our Scottish Tinklers, or

Gipsies, are sprung from the common stock from which are descended those

that are to be found in the other parts of Europe, as well as those that are

scattered over the world generally; what secrecy they observe in all matters

relative to their affairs; what an extraordinary degree of reluctance and

fear they evince in answering questions tending to develop their history;

and, consequently, how difficult it is to learn anything^ satisfactory about

them. [It would be well for the reader to

consider what a Qipsy is, irrespective of the language which he

speaks ; for the race comes before the speech which

it uses. That will be done fully in the Disquisition on the Gipsies. The

language, considered in itself, however interesting it may he, is a

secondary consideration; it may ultimately disappear, while the people who

now speak it will remain.—Ed.]

I fell in one day, on the public road, with an old woman

and her two daughters, of the name of Eoss, selling horn spoons, made by

Andrew Stewart, a Tinkler at Bo'ness. I repeated to the woman, in the shape

of questions, some of the Gipsy words presented in these pages. She at first

affected, though very awkwardly, not to understand what I said, but in a few

minutes, with some embarrassment in her manner, acknowledged that she knew

the speech, and gave me the English of the following words:

Gaugie, man. Grye,

horse.

Managie, woman. Grye-fcmler,

horse-dealer.

Chauvies, children. Roys,

spoons.

I observed to this woman, that I saw no harm in speaking

this language openly and publicly. "None in the least, sir", was her reply.

Two girls, of the name of Jamieson, came one day begging

to my door. They appeared to be sisters, of abont eight and seventeen years

of age, and were pretty decently clothed. Both had light-blue eyes,

light-yellow, or rather flaxen, hair, and fair complexions. To ascertain

whether they were Tinklers or not, I put some Gipsy words to the eldest

girl. She immediately hung down her head, as if she had been detected in a

crime, and, pretending not to understand what was said, left the house; but,

after proceeding about twelve paces, she took courage, turned round, and,

with a smile upon an agreeable countenance, called back, "There are eleven

of us, sir." I had enquired of her how many children there were of her

family. I called both the girls back to my house, and ordered them some

victuals, for which they were extremely grateful, and seemed much pleased

that they were kindly treated. After I had discovered they were Gipsies, I

wormed out of them the following words:

Gaugie, man. Grye,

horse.

Managie, woman. Jucal, dog.

Chauvies, children.

When I enquired of the eldest girl the English of

Jucal, she did not, at first, catch the sound of the word; but

her little sister looked up in her face, and said to her, "Don't you hear?

That is dog. It is dog he means." The other then added, with a downcast

look, and a melancholy tone of voice, "You gentlemen understand all

languages now-a-days."

At another time, four or five children were loitering

about, and diverting themselves, before the door of a house, near

Inverkeithing. The youngest appeared about five, and the eldest about

thirteen years of age. One of the boys, of the name of McDonald, stepped

forward, and asked some money from me in charity. From his importunate

manner of begging, I suspected the children were Gipsies, although their

appearance did not indicate them to be of that race. After some questions

put to them about their parents and their occupations, they gave me the

English of the following words:

Gaugie, man.

Aizel, ass.

Chauvies, children. Lowa,

silver.

Riah, gentleman. Chor,

thief.

Grye, horse. Slavrdie,

prison.

Jucal, dog. Bing, the

devil.

A gentleman, an acquaintance of mine, was in my presence

while the children were answering my words; and as the subject of their

language was new to him, I made some remarks to him in their hearing,

relative to their tribe, which greatly displeased them. One of the boys

called out to me, with much bitterness of expression, "You are a Gipsy

yourself, sir, or you never could have got these words."

Some years since, a female, of the name of Ruthven, was

in the habit of calling at a farm occupied by one of my brothers. My mother,

being interested about the Gipsies, began, on one occasion, to question this

female Tinkler, relative to her tribe, and, among other things, asked if she

was a Gipsy. "Yes," replied Ruthven, "I am a Gipsy, and a desperate,

murdering race we are. I will let you hear me speak our language, but what

the better will you be of that?" She accordingly uttered a few sentences,

and then said, "Now, are you any the wiser of what you have heard? But that

infant," pointing to her child of about five years of age, "understands

every word I speak." "I know," continued the Tinkler, "that the public are

trying to find out the secrets of the Gipsies, but it is in vain." This

woman further stated that her tribe would be exceedingly displeased, were it

known that any of their fraternity taught their language to "strangers." [The

Gipsies are always afraid to say what they would do in such cases. Perhaps

they don't know, but have only a general impression that the individual

would "catch it;" or there may be some old law on the subject. What Ruthven

said of her being a desperate race is true enough, and murderous too, among

themselves as distinguished from the inhabitants generally. Her remark was

evidently part of that frightening policy which keeps the natives from

molesting the tribe. See page 44.—En.] She also mentioned that the

Gipsies believe that the laws which were enacted for their extirpation were

yet in full force against them. I may mention, however, that she could put

confidence in the family in whose house she made these confessions.

On another occasion, a

female, with three or four children, the eldest of whom was not above ten

years of age, came up to me while speaking to an innkeeper, on a public pier

on the banks of the Forth. She stated to us that her property had been

burned to the ground, and her family reduced to beggary, and solicited

charity of us both. After receiving a few half-pence from the innkeeper, she

continued her importunities with an unusual impertinence, and hung upon me

for a contribution. Her barefaced conduct displeased me. I thought I would

put her to the test, and try if she was not a Gipsy. Deepening the tone of

my voice, I called out to her, in an angry manner, "Sarah, jaw dram"— ("

Curse you, take the road.") The woman instantly wheeled about, uttered not

another word, but set off, with precipitation; and so alarmed were her

children, that they took hold of her clothes, to hasten and pull her out of

my presence; calling to her, at the same time, "Mother, mother, come away.

Mine host, the innkeeper, was amazed at the effectual manner in which I

silenced and dismissed the importunate and troublesome beggars. He was

anxious that I should teach him the unknown words that had so terrified the

poor Gipsies; with the design, it appeared to me, of frightening others,

should they molest him with their begging. Had I not proved this family by

the language, it was impossible for any one to perceive that the group were

Gipsies.

In prosecuting my enquiries

into the existence of the Gipsy language, I paid a visit to Lochgellie, once

the residence of four or five families of Gipsies, as already mentioned, and

procured an interview with young Andrew Steedman, a member of the tribe. At

first, he appeared much alarmed, and seemed to think I had a design to do

him harm. His fears, however, were in a short while calmed ; and, after much

reluctance, he gave me the following words and expressions, with the

corresponding English significations. Like a true Gipsy, the first

expression which he uttered, as if it came the readiest to him, was, "Ghoar

a chauvie"—(" rob that person,") which he pronounced with a smile on his

countenance.

The first expression which

the Gipsies use in saluting one another, when they first meet, anywhere, is

"Auteenie, auteenie." Steedman, however, did not give me the English of this

salutation. He stated to me that, at the present day, the Gipsies in

Scotland, when by themselves, transact their business in their own language,

and hold all their ordinary conversations in the same speech. In the course

of a few minutes, Steedman's fears returned upon him. He appeared to regret

what he had done. He now said he had forgotten the language, and referred me

to his father, old Andrew Steedman, who, he said, would give me every

information I might require. I imprudently sent him out, to bring the old

man to me ; for, when both returned, all further communication, with regard

to their speech, was at an end. Both were now dead silent on the subject,

denied all knowledge of the Gipsy language, and were evidently under great

alarm. The old man would not face me at all; and when I went to him, he

appeared to be shaking and trembling, while he stood at the head of his

horses, in his own stable. Young Steedman entreated me to tell no one that

he had given me any words, as the Tinklers, he said, would be exceedingly

displeased with him for doing so. This man, however, by being kindly

treated, and seeing no intention of doing him any harm, became, at an after

period, communicative on various subjects relative to the Gipsies.

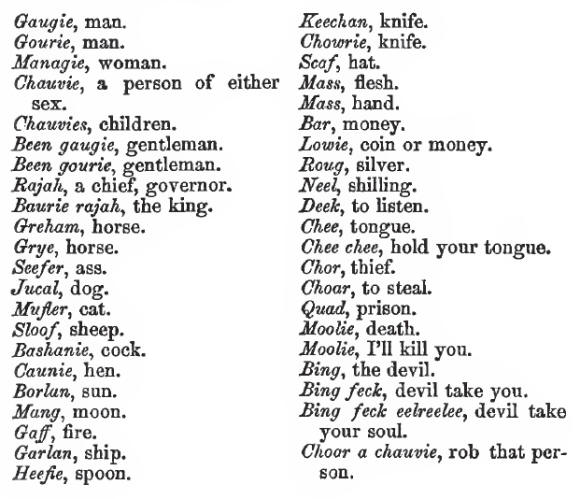

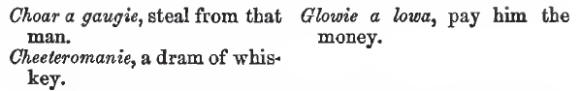

The following are the words

which I obtained during an hour's interrogation of the woman that baffled me

for seven years, and of whom I have said something already:

I observed to this woman that her language would, in

course of time, be lost. She replied, with great seriousness, "It will never

be forgotten, sir; it is in our hearts, and as long as a single Tinkler

exists, it will be remembered." I further enquired of her, how many of her

tribe were in Scotland. Her answer was, "There are several thousand; and

there are many respectable shop-keepers and householders in Scotland that

are Gipsies." I requested of this woman the Gipsy word for God. [Ponqueville,

in his travels, says that the Gipsies in the Levant have no words in their

language to express either God or the soul. Of ten words of the Greek Gipsy,

given by him, five of them are in use in Scotland.— Paris, 1820.] She

said they had no corresponding word for God in their speech;

adding, that she thought " it as well, as it prevented them having their

Maker's name often unnecessarily and sinfully in their mouths." She

acknowledged the justice, and highly approved of the punishment of death for

murder; but she condemned, most bitterly, the law that took away the lives

of human beings for stealing. She dwelt on the advantages which her secret

speech gave her tribe in transacting business in markets. She said that she

was descended from the first Gipsy family in Scotland. I was satisfied that

she was sprung from the second, if not the first, family. I could make out,

with tolerable certainty, the links of her descent for four generations of

Gipsies. I have already described the splendid style in which her ancestors

travelled in Tweed-dale. Her mother, above eighty years of age, also called

at my house. Both were fortune-tellers. It was evident, from this woman's

manner, that she knew much she would not communicate. Like the Gipsy chief,

in presence of Dr. Bright, at Csurgo, in Hungary, she, in a short time,

became impatient; and, apparently, when a certain hour arrived, she insisted

upon being allowed to depart. She would not submit to be questioned any

longer.

Owing to the nature of my enquiries, and more

particularly the fears of the tribe, I could seldom venture to question the

Gipsies regarding their speech, or their ancient customs, with any hope of

receiving satisfactory answers, when a third party was present. The

following, however, is an instance to the contrary; and the facts witnessed

by the gentleman who was with me at the time, are, besides the testimony of

the Gipsies themselves, convincing proofs that these people, at the present

day, in Scotland, can converse among themselves, on any ordinary subject, in

their own language, without making use of a single word of the English

tongue. [Had a German listened a whole day to a

Gipsy conversation, he would not have understood a single expression.—Orellmann.

The dialect of the English Gipsies, though mixed with English, is

tolerably pure, from the fact of its being intelligible to the race in the

centre of Russia.—Borrow.—Ed.]

In May, 1829, while near the Manse of Inverkeithing, my

friend and I accidentally fell in, on the high road, with four children, the

youngest of whom appeared to be about four, and the eldest about

thirteen, years of age. They were accompanied by a woman, about twenty years

old, who had the appearance of being married, but not the mother of any of

the children with her. Not one of the whole party could have been taken for

a Gipsy, but all had the exact appearance of being the family of some

indigent tradesman or labourer. Excepting the woman, whose hair was dark,

all of the company had hair of a light colour, some of them inclining to

yellow, with fair complexions. In not one of their countenances could be

seen those features by which many pretend the Gipsies can, at all times, be

distinguished from the rest of the community. The manner, however, in which

the woman, at first, addressed me, created in my mind a suspicion that she

was one of the tribe. In order to ascertain the fact, I put a question to

her in Gipsy, in such a manner that it might appear to her that I was quite

certain she was one of the fraternity. She immediately smiled at my

question, held down her head, cast her eyes to the ground, then appeared as

if she had been detected in something wrong, and pretended not to understand

what I said. One of the children, however, being thrown entirely off his

guard, immediately said to her, "You know quite well what he says!" The

woman, recovering from her surprise and confusion, and being assured she had

nothing to fear from me, now answered my question. She also replied to every

other interrogation I put to her, without showing the least fear or

hesitation. After I had repeated a few words more, and a sentence in the

Gipsy tongue, one of the boys exclaimed, "He has good cant!" and then

addressed me entirely in the Gipsy language. (All the Gipsies, as I have

already mentioned, call their language card, for the purpose of concealing

their tribe.) The whole party seemed extremely happy that I was acquainted

with their speech. The woman put several questions to me, in return, some of

which were wholly in her own peculiar tongue. She asked my name, place of

residence, and whether I was a hawken—that is a Gipsy. She further enquired

whether my friend was also a hawker; adding, with a smile, that she was sure

I was a tramper. The children sometimes conversed among themselves wholly in

their own language; and, when I could not understand the woman, as she

requested, in her own speech, to know my name, &c„ one of them instantly

interpreted the sentence into English for me. One of the oldest boys,

however, thinking I was only pretending to be ignorant of their speech,

observed, in English, to his companions, "I am sure he is a tramper, and can

speak as good cant as any of us." To keep up the character, my friend told

them that I had been a tramper in my youth, but that I had now nearly lost

the language. On hearing this, the woman, with great earnestness, exclaimed,

" God bless the gentleman!" In order to confirm their belief that I was one

of their tribe, I bade the woman good-day in her own tongue, and parted with

them. She informed me, on leaving, that she resided at Banff, but that her

husband was then at Perth.

During the short interview which I had with these

Gipsies, I collected the following words:

The method I adopted with them, as I have already hinted,

was to ask them the English of the words I gave them in Gipsy, so that the

answers I got were confirmations of the same words collected from other

individuals, and which I drew from memory for the occasion. Had I attempted

to write down any of their sentences, it would have instantly shut the door

to all further conversation on the subject, and, in all probability, the

Gipsies would have taken to their heels, muttering imprecations against me

for having insulted them. Of this I was satisfied, that had I really been

acquainted with their speech, these Gipsy children could have kept up a

regular and connected conversation with me, with the greatest fluency, and

without their sentences being intermixed with any English or

Scotch words whatever, a fact which has been repeatedly stated to me by the

Gipsies.

In confirmation of these facts, I shall transcribe a

letter addressed to me by the gentleman who was present on the occasion. [This

letter is interesting to the extent that it illustrates the amount of

knowledge possessed by the Scottish community, generally, regarding the

subject of the Gipsies.—En.]

Inverkeithing, 25th May, 1829.

"My Dear Sir:

"Agreeably to your desire, I have looked over that part

of your manuscript of the Scottish Gipsies which details the particulars of

a short and accidental interview which we had with a woman and four

children, whom we met near Inverkeithing Manse, on the 22d inst., and who

turned out to be Gipsies. I have no hesitation in averring that your

statements, to my knowledge, are substantially correct— being present during

the whole conversation which took place with the individuals mentioned. It

was the first time ever heard the Gipsy language spoken, and it appeared

quite evident that those Gipsies could converse, in a regular and connected

manner, on any subject, without making use of a single English word ; and

which particularly appeared from the questions which they put to you, as

well as from the conversation which they had among themselves, in their own

peculiar speech : and that, otherwise, the woman and children had not, in

the colour of their hair, complexion, and general appearance, any

resemblance to those people whom I always considered to be Gipsies. I am,

&c,

"JAMES H. COBBAN,

Deputy Compt. of Customs, Inverkeithing.

"Mr. Walter Simson,

Supt. of Quarantine, Inverkeithing."

I have already mentioned having succeeded in obtaining a

few words of Gipsy, from two sisters, of the name of Jamie-son, who came

begging to my door. I had reason to suppose they would acquaint their

relatives of having been questioned in their own speech, and would greatly

exaggerate my knowledge of it; for I always observed that the individuals

with whom I conversed were at first impressed with a belief that I knew much

more of it than I really did.

During the following summer, a brother and a cousin of

these girls called at my house, selling baskets. The one was about

twenty-one, the other fifteen, years of age. I happened to be from home, but

one of my family, suspecting them to be Gipsies, invifed them into the

house, and mentioned to them, (although very incorrectly,) that I understood

every word of their speech. "So I saw," replied the eldest lad, "for when he

passed us on the road, some time ago, I called, in our language, to my

neighbour, to come out of the way, and he understood what I said, for he

immediately turned round, and looked at us." I, however, knew nothing of the

circumstance; I did not even recollect having seen them pass me. It is

likely, however, I had been examining their appearance, and it is as likely

they had been trying if I understood their speech. At all events, they

appeared to have known me, while I was entirely ignorant of who they were,

and to have had their curiosity excited, on account, as I imagined, of their

relatives having told them I was acquainted with their language. This

occurrence produced a wonderful effect upon the two lads, for they appeared

pleased to think I could speak their language. At this moment, one of my

daughters, about seven years of age, repeated, in their hearing, the Gipsy

word for pot, having picked it up from hearing me mention it. The young

Tinklers now thought they were in the midst of a Gipsy family, and seemed

quite happy. "But are you really a hawker?" I asked the eldest

of them. "Yes, sir," he replied; "and to show you I am no impostor, I will

give you the names of everything in your house;" which, in the presence of

my family, he did, to the extent I asked of him. "My speech," he continued,

"is not the cant of packmen, nor the slang of common thieves."

But Gipsy-hunting is like deer-stalking. In prosecuting

it, it is necessary to know the animal, its habits, and the locality in

which it is to be found. I saw the unfavourable turn approaching: the

Gipsies' time was up ; their patience was exhausted. I dropped the subject,

and ordered them some refreshment. On their taking leave of me, I said to

them, "Do you intend coming round this part of the country again?" (I need

not have asked them such a question as that.) " That we do, sir ; and we

will not fail to come and see you again." They thus left me, with the strong

impression on their minds, that I was a nawken, like themselves, but

a riah—a gentleman Gipsy. I waited patiently for their return, which

would happen in due season, on their half-yearly tramp. Everything

looked so favourably, circumstances had contributed so fortunately, to the

end which I had so much at heart, that I looked upon the information to be

drawn from these poor Tinkler lads, with as much solicitude and avarice as

one would who had discovered a treasure hid in his field.

This species of Gipsy-hunting, I believe, I had

exclusively to myself. I had none of the difficulties to contend with, which

would be implied in the field of it having been gone over by others before

me. That kind of Gipsy-hunting which implied imprisonment, banishment, and

hanging, was a thing of which the Gipsies had had sad experience; if not in

their own persons, at least in that which the traditions of their tribe had

so carefully handed down to them. Besides this, the experience of the daily

life of the members of their tribe afforded an excellent school of training,

for acquiring a host of expedients for escaping every danger and difficulty

to which their habits exposed them. But so thoroughly had they preserved

their secrets, and especially the grand one—their language—that they came to

their wits' end how to understand, and how to act in, the new sphere of

danger into which they were now thrown, or even to comprehend its nature.

Such was the advantage which education and enlightenment had given their

civilized neighbour over them. How could they imagine that the

commencement of my knowledge of their language had been drawn from boohs?

What did some of them know of books, beyond, perhaps, a youth

sent to school, where, owing to his restless and unsettled

good-for-nothingness, he would advance little beyond his alphabet? For we

know that some Gipsies are so intensely vain as to send a child to school,

merely to brag before their civilized neighbours that their children have

been educated. How could tliey comprehend that their language

had found, or could find, its way into boohs? The thing to them was

impossible; the idea of it could not, by any exertion of their own, even

enter into their imagination. The danger to arise from such a quarter was

altogether beyond their capacity of comprehension. Knowing, however, that

there was danger of some singular nature surrounding them, yet being unable

to comprehend it, they flickered about it, like moths about a candle; till

at last they did come to comprehend, if not its origin, or extent, at least

its tendency, and the consequences to which it would lead.

According to promise, the eldest of the Gipsy boys called

at my house, in about six months, accompanied by his sister. He was selling

white-iron ware, for he was a tin-smith by occupation. Without entering into

any preliminary conversation, for the purpose of smoothing the way for more

direct questions, I took him into my parlour, and at once enquired if he

could speak the Tinkler language? He applied to my question the

construction that I doubted if he could, and the consequences which that

would imply, and answered firmly, "Yes, sir; I have been bred in that line

all my life." "Will you allow me," said I, "to write down your words?" "O

yes, sir; you are welcome to as many as you please." "Have you names for

everything, and can you converse on any subject, in that language?" "Yes,

sir; we can converse, and have a name for everything, in our own speech." I

now commenced to "make hay while the sun shone," as the phrase runs; for I

knew that I could have only about an hour with the Gipsy, at the most. The

following, then, are the words and sentences which I took down, on this

occasion:

This young man sang part of two Gipsy songs to me, in

English; and then, at my request, he turned one of them into the Gipsy

language, intermingled a little, however, with English words; occasioned,

perhaps, by the difficulty in translating it. The subject of one of the

songs was that of celebrating a robbery, committed upon a Lord Shandos; and

the subject of the other was a description of a Gipsy battle. The courage

with which the females stood the rattle of the cudgels upon their heads was

much lauded in the song. Like the Gipsy woman with whom I had no less than

seven years' trouble ere getting any of her speech, this Gipsy lad became,

in about an hours time, very restless, and impatient to be gone. The true

state of things, in this instance, dawned upon his mind. He now became much

alarmed, and would neither allow me to write down his songs, nor stop to

give me any more of his words and sentences. His terror was only exceeded by

his mortification; and, on parting with me, he said that, had he, at first,

been aware I was unacquainted with his speech, he would not have given me a

word of it.

As far as I can judge, from the few and short specimens

which I have myself heard, and had reported to me, the subjects of the songs

of the Scottish Gipsies, (I mean those composed by themselves,) are chiefly

their plunderings, their robberies, and their sufferings. The numerous and

deadly conflicts which they had among themselves, also, afforded them themes

for the exercise of their muse. My father, in his youth, often heard them

singing songs, wholly in their own language. They appear to have been very

fond of our ancient Border marauding songs, which celebrate the daring

exploits of the lawless freebooters on the frontiers of Scotland and

England. They were constantly singing these compositions among themselves.

The song composed on Hughie Graeme, the horse-stealer, published in the

second volume of Sir Walter Scott's Border Minstrelsy, was a great favourite

with the Tinklers. As this song is completely to the taste of a Gipsy, I

will insert it in this place, as affording a good specimen of that

description of song in the singing of which they take great delight. It will

also serve to show the peculiar cast of mind of the Gipsies.

HUGHIE THE GILEME.

Gude Lord Scroope's to the hunting gane,

He has ridden o'er moss and muir;

And he has grippit Hughie the Graeme,

For stealing o' the Bishop's mare.

"Now, good Lord Scroope, this may not he!

Here hangs a broadsword by my side;

And if that thou canst conquer me,

The matter it may Boon be tryed."

"I ne'er was afraid of a traitor-thief;

Although thy name be Hughie the Graeme,

I'll make thee repent thee of thy deeds,

If God but grant me life and time."

"Then do your worst now, good Lord Scroope,

And deal your blows as hard as you can I

It shall be tried, within an hour,

Which of us two is the better man."

But as they were dealing their blows so free,

And both so bloody at the time,

Over the moss came ten yeomen so tall,

All for to take brave Hughie the Graeme.

Then they hae grippit Hughie the Graeme,

And brought him up through Carlisle town;

The lasses and lads stood on the walls, Crying,

"Hughie the Grasme, thou'se ne'er gae down."

Then hae they chosen a jury of men,

The best that were in Carlisle town;

And twelve of them cried out at once,

"Hughie the Graeme, thou must gae down."

Then up bespak him gude Lord Hume,

As he sat by the judge's knee,—

"Twenty white owsen, my gude lord,

If you'll grant Hughie the Graeme to me."

" O no, O no, my gude Lord Hume!

For sooth and sae it manna be;

For, were there but three Graemes of the name,

They suld be hanged a' for me."

'Twas up and spake the gude Lady Hume,

As she sat by the judge's knee,—

"A peck of white pennies, my gude lord judge,

If you'll grant Hughie the Graeme to me."

"O no, O no, my gude Lady Hume!

For sooth and so it must na be;

Were he but the one Graeme of the name,

He suld be hanged high for me."

"If I be guilty," said Hughie the Graeme,

"Of me my friends shall have small talk;"

And he has louped fifteen feet and three,

Though his hands they were tied behind his back.

He looked over his left shoulder,

And for to see what he might see;

There was he aware of his auld father,

Came tearing his hair most piteouslie.

"O I hald your tongue, my father," he says,

"And see that ye dinna weep for me!

For they may ravish me o' my life,

But they canna banish me fro Heavin hie.

"Fare ye weel, fair Maggie, my wife!

The last time we came ower the muir,

'Twas thou bereft me of my life,

And wi' the Bishop thou play'd the whore.

"Here, Johnie Armstrang, take thou my sword,

That is made o' the metal sae fine;

And when thou comest to the English side,

Remember the death of Hughie the Gramme."*

[On mentioning to Sir "Walter Scott, when at Abbotsford,

that the Gipsies were very partial to Hughie the Graeme, he caused his

eldest daughter, afterwards Mrs. Lockhart, to sing this ancient Border song,

which she readily did, accompanying her voice with the harp. We were, at the

time, in the room which contained his old armour and other antiquities; to

which place he had asked me, after tea, to hear his daughter play on the

harp. She sang Hughie the Graeme, in a plain,

simple, unaffected manner, exactly in the style in which I have heard the

humble country-girls singing the Bame song, in the south of Scotland. Sir

Walter was much interested about the Gipsies; and when I repeated to him a

short sentence in their speech, he, with great feeling, exclaimed, "Poor

things! do you hear that?" This was the first time, I believe, that

he ever heard a Scottish Gipsy word pronounced. It appeared to me that the

mind of the great magician was not wholly divested of the fear that the

Gipsies might, in some way or other, injure his young plantations.]

I will now give the testimony of the Gipsy chief from

whom I received the " blowing up" alluded to, by Mr. Laid-law, in the

Introduction to the work.

One of the greatest fairs in Scotland is held, annually,

on the 18th day of July, at St. Boswell's Green, in Roxburghshire. I paid a

visit to this fair, for the purpose of taking a view of the Gipsies. An

acquaintance, whom I met at the fair, observed to me, that he was sure if

any one could give me information regarding the Tinklers, it would be

old------, the homer, at------. To ensure a kind reception from the Gipsies,

it was agreed upon, between us, that I should introduce myself by mentioning

who my ancestors were, on whose numerous farms, (sixteen, rented by my

grandfather, in 1781, [These sixteen farms

embraced about 25,000 acres of mountainous land, and maintained 13,000

sheep, 100 goats, 260 cattle, 60 horses, 20 draught-oxen, and 60 dogs; 29

shepherds, 26 other servants, and 16 cotters, making, with their families,

228 souls, supported by my ancestor's property, as that of a Scotch

gentleman-farmer. On the farms mentioned, which lay in Mid-Lothian,

Tweed-dale, and Selkirkshire, the Gipsies were allowed to remain as long as

they pleased; and no loss was ever sustained by the indulgence.])

their forefathers had received many a night's quarters, in their out-houses.

We soon found out the old chieftain, sitting in a tent, in the midst of

about a dozen of his tribe, all nearly related to, him. The moment I made

myself known to them, the whole of the old persons immediately expressed

their gratitude for the humane treatment they, and their forefathers, had

received at the farms of my relatives. They were extremely glad to sec me;

and "God bless you," was repeated by several of the old females. "Ay," said

they, "those days are gone. Christian charity has now left the land. We know

the people growing more hard and uncharitable every year." I found the old

man shrewd, sensible, and intelligent; far beyond what could have been

expected from a person of his caste and station in life. He, besides,

possessed all that merrincss and jocularity which I have often observed

among a number of the males of his race. After some conversation with this

chief, who appeared about eighty years of age, I enquired if his people,

who, in large bands, about sixty years ago, traversed the south of Scotland,

had not an ancient language, peculiar to themselves. He hesitated a little,

and then readily replied, that the Tinklers had no language of their own,

except a few cant words. I observed to him that he knew better—that the

Tinklers had, beyond dispute, a language of their own ; and that I had some

knowledge of its existence at the present day. He, however, declared that

they had no such language, and that I was wrongly informed. In the hearing

of all the Gipsies in the tent, I repeated to him four or five Gipsy words

and expressions. At this he appeared amazed ; and on my adding some

particulars relative to some of the ancestors of the tribe then present,

enumerating, I think, three generations of their clan, one of the old

females exclaimed, "Preserve me, he kens a' about us!" The old chief

immediately took hold of my right hand, below the table, with a grasp as if

he were going to shake it; and, in a low and subdued tone of voice, so as

none might hear but myself, requested me to say not another word in the

place where we were sitting, but to call on him, at the town of------, and

he would converse with me on that subject. I considered it imprudent to put

any more questions to him relative to his speech, on this occasion, and

agreed to meet him at the place he appointed.

Several persons in the tent, (it being one of the public

booths in the market,) who were not Gipsies, were equally surprised, when

they observed an understanding immediately take place between me and the

Tinklers, by means of a few words, the meaning of which they could not

comprehend. A farmer, from the south of Scotland, who was present in the

tent, and had that morning given the Tinklers a lamb to eat, met me, some

days after, on the banks of the Yarrow. He shook his head, and observed,

with a smile, "Yon was queer-looking wark wi' the Tinklers."

As I was anxious to penetrate to his secret speech, I

resolved to keep the appointment with the Gipsy, whatever might be the

result of our meeting, and I therefore proceeded to the town which he

mentioned, eleven days after I had seen him at the fair. On enquiring of the

landlord of the principal inn, at which I put up my horse, where the house

of------, the Tinkler, was situated in the town, he appeared surprised, and

eyed me all over. He told me the street, but said he would not accompany me

to the house, thinking that I wished him to go with me. It was evident that

the landlord, whom I never saw before, considered himself in bad company, in

spite of my black clothes, black neck-cloth, and ruffles aforesaid, and was

determined not to be seen on the street, either with me or the Tinkler. I

told him I by no means wished him to accompany me, but only to tell me in

what part of the town the Tinkler's house was to be found.

On entering the house, I found the old chief sitting,

without his coat, with an old night-cap on his head, a leathern apron around

his waist, and all covered with dust or soot, employed in making spoons from

horn. After conversing with him for a short time, I reminded him of the

ancient language with which he was acquainted. He assumed a grave

countenance, and said the Tinklers had no such language, adding, at the same

time, that I should not trouble myself about such matters. He stoutly denied

all knowledge of the Tinkler language, and said no such tongue existed in

Scotland, except a few cant words. I persisted in asserting that they were

actually in possession of a secret language, and again tried him with a few

of my words ; but to no purpose. All my efforts produced no effect upon his

obstinacy. At this stage of my interview, I durst not mention the word

Gipsy, as they are exceedingly alarmed at being known as Gipsies. I now

signified that he had forfeited his promise, given me at the fair, and rose

to leave him. At this remark, I heard a man burst out a-laughing, behind a

partition that ran across the apartment in which we were sitting. The old

man likewise started to his feet, and, with both his sooty hands, took hold

of the breast of my coat, on either side, and, in this attitude, examined me

closely, scanning me all over from head to foot. After satisfying himself,

he said, " Now, give me a hold of your hand—farewell—I will know you when I

see you again." I bade him good-day, and left the house.

[I am convinced the Gipsies have a method of

communicating with one another by their hands and fingers, and it is likely

this man tried me, in that way, both at the fair and in his own house. I

know a man who has seen the Gipsies communicating their thoughts to each

other in this way. "Bargains among the Indians are conducted in the most

profound silence, and by merely touching each

other's hands. If the seller takes the whole band, it implies a thousand

rupees or pagodas; five fingers import five hundred ; one finger, one

hundred; half a finger, fifty; a single joint only ten. In this

manner, they will often, in a crowded room, conclude the most important

transactions, without the company suspecting that anything whatever was

doing."—Historical Account of Travels in Asia, by Hugh Murray.

"Method of the English selling their cargoes, at Jedda,

to the Turks : Two Indian brokers come into the room to settle the

price, one on the part of the Indian captain, the other on that of the buyer

or Turk. They are neither Mahommedans nor Christians, but have credit with

both. They sit down on the carpet, and take an Indian shawl, which they

carry on their shoulders like a napkin, aud spread it over their hands. They

talk, in the meantime, indifferent conversation, of the arrival of ships

from India, or ef the news of the day, as if they were employed in no

serious business whatever. After about twenty minutes spent in handling each

other's fingers, below the shawl, the bargain is concluded, say for nine

ships, without one word ever having been spoken on the subject, or pen or

ink used in any shape whatever."—Bruce'* Travels.]

I had now no hope of obtaining any information from this

man, regarding his peculiar language. I had scarcely, however, proceeded a

hundred yards down the street, from the house, when I was overtaken by a

young female, who requested me to return, to speak with her father. I

immediately complied. On reaching the door, with the girl, I met one of the

old man's sons, who said that he had overheard what passed between his

father and me, in the house. He assured me that his father was asliamed

to give me his language; but that, if I would promise not to publish

their names, or place of residence, he would himself give me some of their

speech, if his father still persevered in his refusal. I accordingly agreed

not to make public the names, and place of residence, of the family. I again

entered the little factory of horn spoons. Matters were now, to all

appearance, quite changed. The old man was very cheerful, and seemed full of

mirth. "Come away," said he; "what is this you are asking after? I would

advise you to go to Mr. Stewart, at Hawiek, and he will tell you everything

about our language." "Father," said the son, who had resumed his place

behind the partition before mentioned, "you know that Mr. Stewart will give

our speech to nobody." The old chief again hesitated and considered, but,

being urged by his son and myself, he, at last, said, "Come away, then; I

will tell you whatever you think proper to ask me. I gave you my oath, at

the fair, to do so. Get out your paper, pen and ink, and begin." He gave me

no other oath, at the fair, than his word, and taking me by the hand, that

he would converse with me regarding the speech of the Tinklers. But, I

believe, joining hands is considered an oath in some countries of the

Eastern world. I was fully convinced, however, that he was ashamed to

give me his speech, and that it was with the greatest reluctance he

spoke one word on the subject. The following are the words and sentences

which I collected from him:

{It is interesting to notice the reason for this old

Gipsy chief being eo backward in giving our author some of his language. "He

was ashamed to do it." Pity it is that there should be a man in Scotland,

who, independent of personal character, should be ashamed of euch a thing.

Then, see how the Gipsy woman, in our author's house, said that " the public

would look upon her with horror and contempt, were it known she could speak

the Gipsy language." And again, the two female Gipsies, Who would rather

allow themselves to be murdered, than give the meaning of two Gipsy words to

Sauchie colliers, for the reason that "it would have exposed their tribe,

and made themselves odious to the world." And all for knowing the Gipsy

language!—which would be considered an accomplishment in another person !

What frightful tyranny! Mr. Borrow, as we will by and by see, saye a great

deal about the law of Charles III, in regard to the prospects of the Spanish

Gipsies; But there is a law above any legislative enactment—the law of

society, of one's fellow-creatures—which bears so hard upon the Gipsies; the

despotism of caste. If Gipsies, in such humble circumstances, are so afraid

of being known to be Gipsies, we can form some idea of the morbid

sensitiveness of those in a higher sphere of life.

The innkeeper evidently thought himself in bad company,

when our author asked him for the Tinkler's ho'use, or that any intercourse

with a Tinkler would contaminate and degrade him. In this light, read an

anecdote in the history of John Bunyan, who was one of the same people, as I

shall afterwards show. On applying for his release from Bedford jail, his

wife said to Justice Hale, "Moreover, my lord, I have four small children

that cannot help themselves, of .which one is blind, and we have nothing to

live upon but the charity of good people." Thereat, Justice Hale, looking

very aoberly on the matter, said, " Alas, poor woman!" "What is his

calling?" continued the judge. And some of the company, that stood by, said,

(evidently in interruption, and with a bitter sneer,) "A Tinker, my lord!"

"Yes," replied Bunyan's wife, "and because he is a Tinker, and a poor man,

therefore he is despised, and cannot have justice." Noble woman! wife of a

noble Gipsy! If the world wishes to know who John Bunyan really was, it can

find him depicted in our author's visit to this Scottish Gipsy family, where

it can also learn the meaning of Bunyan, at a time when Jews were legally

excluded from England, taking so much trouble to ascertain whether he was of

that race, or not From the present work generally, the world can learn the

reason why Bunyan said nothing of his ancestry and nationality, when giving

an account of his own history.—Ed. ]

* Nawken has a number

of significations, such as Tinkler, Gipsy, a wanderer, a worker in iron,

a man who can do anything for himself in the mechanical arts, &c, &c.

I was desirous to learn, from this Gipsy, if there were

any traditions among the Scottish Gipsies, as to their origin, and the

country from which they came. He stated that the language of which he had

given me a specimen was an Ethiopian dialect, used by a tribe of thieves and

robbers ; and that the Gipsies were originally from Ethiopia, although now

called Gipsies. [The tradition among the

Scottish Gipsies of being Ethiopians, whatever weight the reader may attach

to it, dates as far hack, at least, as the year 1616; for it is mentioned in

the remission under the privy seal, granted to William Auchterlony, of

Cayrine, for resetting John Faa and his followers. Seepage 118.—Ed.]

He now spoke of himself and his tribe by the name of Gipsies, without

hesitation or alarm. "Our Gipsy language," added he,"is softer than your

harsh Gaelic." He was at considerable pains to give me the proper sound of

the words. The letter a is pronounced broad in their language, like

aw in paw, or a in water ; and ie, or ee, in the last

syllable of a great many words, are sounded short and quick; and ch

soft, as in church. Their speech appears to be copious, for, said he, they

have a great many words and expressions for one thing. He further stated

that the Gipsy language has no alphabet, or character, by which it can be

learned, or its grammatical construction ascertained. He never saw any of it

written. I observed to him that it. would, in course of time, be lost. He

replied, that "so long as #ier.e, existed two Gipsies in Scotland, it would

never be lost." He informed me that every one of the Yetholm Tinklers spoke

the language; and that, almost all those persons who .were selling

earthen-ware at St. Bps-well's fair were Gipsies. I counted myself

twenty-four families, with earthen-ware, and nine female heads of families,

selling articles made of horn. These thirty:three families, together with a

great many single Gipsies scattered through the fair, would amount to above

three hundred Gipsies on the spot. He further mentioned that none of the

Yetholm Gipsies were at the market. The old man also informed me that a

great number of our horse-dealers are Gipsies. "Listen attentively," said

he, "to our horse-coupers, in a market, and you will hear them speaking in

the Gipsy tongue." I enquired how many there were in Scotland acquainted

with the language. He answered, "There are several thousand." I further