|

HAVING thus endeavoured to

give a general outline of that portion of the county of Dunbarton which is

more especially the subject of this volume, it will be well to mention some

details regarding the ancient family of Lennox, to whose representatives at

one time the whole of Row and Cardross belonged. The name was originally

Leven-ach, a Gaelic term signifying the "field of the Leven." In the plural,

Levenachs, was the name given to the extensive possessions of the Earls of

the district between the river Leven and the Gareloch, and, in process of

time, became shortened into Lennox. It is believed that the founder of the

family was Arkyll, a Saxon baron of Northumberland, who also owned large

estates in Yorkshire, and who rebelled against William the Conqueror. Along

with many other Saxon barons in 1070, he fled to Scotland and received from

Malcolm Canmore a large tract of land in the counties of Dunbarton and

Stirling. Arkyll married for his second wife a Scottish lady, whose son

Alwyn was understood to have been first Earl of Lennox, and to have died in

1160. His son Alwyn being very ycung when his father died, the Earl of

Huntington, the brother of William the Lion, was appointed guardian of Alwyn

for a long period. His son Aulay got Faslanc, at the upper end of the

Gareloch, for his patrimony, and he gave to the monastery of Paisley "the

church of Rosneath with all its just pertinents in pure and perpetual alms,

the charter having been confirmed to Maldouin, Earl of Lennox, his brother,

and by King Alexander II. on 12th March, in the twelfth year of his reign.

He also made a donation to that monastery of a salt pit in Rosneath, and of

wood for repairs. He also gave to it all the tracts of nets through the

whole of Gareloch for catching salmon, and other fish, reserving to himself

and to his heirs every fourth salmon taken through these tracts." Maldouin,

third Earl, succeeded his father in 1225, and was one of the guarantees on

the part of King Alexander III. when the differences between him and Henry

III. of England were arranged in 1237. Up to this time the castle of

Dunbarton had been the principal messuage of the Earls of Lennox, but, after

1238, when he received a new charter of the earldom, neither the castle,

territory, and harbour adjacent remained in the Lennox family. Ever since,

the castle has been a royal fortress, and the town of Dunbarton was, in

1222, erected into a free royal burgh with extensive privileges.

Malcolm the fifth Earl was,

in 1292, one of the nominees on the part of the elder Bruce in his

competition for the Crown of Scotland with Baliol, and, in 1206, he

assembled his followers, and with other Scottish leaders, invaded Cumberland

and assaulted Carlisle. He was slain at the battle of Halidon Hill on 19th

July, 1333. His son Donald, sixth Earl, was one of the nobles present in the

parliament at Edinburgh in September, 1337, and he became bound for the

payment of the ransom of King David II. He was present at the coronation of

Robert II. at Scone, 16th March, 1371, and on the following day swore homage

and fealty to him. He died in 1373, and, having no male issue, the direct

male line ceased with him. The earldom devolved on his only daughter

Margaret, who married her cousin, and nearest heir male of the family,

Walter, son of Allan de Fasselane who, in her right, in accordance with the

territorial nature of feudal dignities at that period, became seventh Earl

of Lennox. In 1385 the Countess Margaret and her husband made a resignation

of the dignity in favour of their son Duncan who, in consequence, became

Earl of Lennox in his father's lifetime. Duncan had no male issue, and was

left a widower, with three daughters, the eldest of whom. Isabella, married

in 1391, Murdoch, Duke of Albany, who became Regent of Scotland. The

contract of marriage, a very curious document, was signed at the old castle

in Inchmurrin on Loch Lomond, which was then the principal residence of the

Earls of Lennox, Although his connection with the Duke of Albany made

Duncan, Earl of Lennox, one of the most powerful noblemen in the kingdom,

yet he thereby incurred the wrath of King James I., who, on his return from

his long captivity in England, caused the Earl to be beheaded at Stirling,

along with his son-in-law, on 25th May, 1425, when about eighty years of

age. His grandson, Walter of the Levenax, was beheaded at Stirling on the

previous day, a cruel and unnecessary act, and his widowed mother spent the

remainder of her days on Inchmurrin. She was a lady of deep piety and

benevolence of character, and spent her life in the exercise of an extensive

charity, and, about 1450, founded the Collegiate Church at Dunbarton, to

which was attached an almshouse for poor beadsmen.

Both of the Duchess

Isabella's sisters appear to have predeceased her, and, at her death, took

place what is known as the partition or dismemberment of the Lennox. The

celebrated Sir John Stewart, created Lord Darnley about 1460, was served

heir to his grandfather, Duncan, Earl of Lennox, in 1473, in the half of the

Earldom of Lennox, and in its principal messuage. In 1489 he took arms

against the young King, when his fortresses of Crookston and Dunbarton were

besieged, the latter by the Earl of Argyll. The castle, which was defended

by his four sons, had to surrender, after a siege of six weeks, but be

succeeded in making his peace with the King, and obtaining a full pardon for

himself and his followers. Owing to a dispute regarding the estates which

occurred with the Haldanes of Gleneagles, who claimed to represent the

ancient Earls of Lennox, and the arbiters having awarded the former a large

part of the property, the territory of the Lennox was now much curtailed of

its importance. Matthew Stewart, Earl of Lennox, succeeded his father in

1494, and in 1503 he obtained a grant from James IV. of the sheriffdom of

Dunbartonshire, which was united to the earldom, and made hereditary in the

family of Lennox. Along with the Earl of Argyll, Lennox led the right wing

of the Scottish army at the battle of Flodden, the men under their command

being almost entirely raised in the western counties. Both the Earls were

slain at that disastrous battle, and John succeeded as Earl of Lennox,

playing an important part during the turbulent minority of James V. In 1524

he warmly supported the Queen-mother when she declared he son King James of

age, though then only in his thirteenth year. He was a member of the new

secret council appointed in 1526, and at the head of a force of 10,000 men

marched from Stirling to Edinburgh for the rescue of the King, who was

almost a prisoner in the hands of the powerful house of Douglas. The Earl of

Arran and the Hamiltons, with a strong army, met Lennox near Linlithgow, and

in the battle which ensued the latter was slain in cold blood after being

taken prisoner by Hamilton of Finnart. Sir Andrew Wood of Largo found the

Earl of Arran weeping over the expiring Lennox, deploring his loss, and

exclaiming "The wisest, the best, the bravest man in Scotland has fallen

this day."

Matthew, his eldest son,

spent the early part of his life in the service of the King of France, and

in the wars in Italy, where he greatly distinguished himself. This nobleman

also was a chief actor in the stirring events which occurred during the

early years of Mary Queen of Scots, and was the rival of Bothwell for the

favour of the Queen-dowager. In 1544, an agreement was entered into at

Carlisle between Lennox, Glencairn, and Henry VIII., in which the latter

promised to Lennox the government of Scotland, and the hand of his niece,

the Lady Margaret Douglas, while the two Earls engaged to use every effort

to seize and deliver the young Queen with the principal Scottish fortresses,

into Henry's hands. Soon afterwards he was married to Lady Margaret,

receiving with her lands in England to the annual value of 6800 merks Scots.

In 1544 he resided at Carlisle, and in 1545, he negotiated with Donald, Lord

of the Isles, and other nobles for an invasion of Scotland, which was

however postponed. In consequence, Lennox was found guilty of treason, at a

Parliament held at Stirling, and his lands forfeited. After a residence of

twenty years in England, he was recalled by Queen Mary in December, 1564,

and his forfeiture rescinded. Being the father of the ill-fated Lord Darnley,

Queen Mary's husband, and grandfather of James VI., he was, in July, 1570,

elected Regent of Scotland. Having called a Parliament to be held at

Stirling, in September, 15711, the Queen's party formed a design, planned by

Kirkcaldy of Grange, to surprise the Parliament and seize the Regent. The

attack, however, failed, but, in the skirmish which ensued, the Earl of

Lennox was stabbed in the back by Captain Calder, and died that evening in

the Castle of Stirling, where he was interred in the Chapel Royal, and his

virtues commemorated in a Latin epitaph by the celebrated George Buchanan.

The Earldom of Lennox, by

right of blood relationship, now devolved on King James VI., as heir of his

grandfather, and in 1572, this and the Lordship of Darnley, with all the

family estates and jurisdictions, were granted to Charles, Lord Darnley's

younger brother. He was the father of the unfortunate Lady Arabella Stuart,

whose proximity to the throne rendered her the innocent victim of State

policy. She died in 1615, aged thirty-eight, and was buried in Westminster

Abbey, where most of the subsequent Dukes of Lennox of this family were

interred. Robert Stuart, son of John Earl of Lennox, succeeded to the title.

lie was at one time Provost of the Collegiate Church of Dunbarton, complied

with the Reformation, and during his brother's short Regency, was appointed

Priorof St. Andrews. The seventh Earl, and first Duke of Lennox of this

name, was Esme Stuart, who had been educated in France, and, on his arrival

in Scotland in 1579, was made Abbot of Arbroath, besides receiving other

honours. He became a special favourite with the King, and was created Duke

of Lennox, and appointed Lord High Chamberlain of Scotland. However, the

jealousy of the Scottish nobility became so great that the King was

constrained to sign an order for the departure of Lennox from Scotland. His

son Ludovick, second Duke of Lennox, was distinguished in various ways, and

enjoyed the favour of King James, who bestowed on him all the estates and

honours held by his father, arid, in addition, created him Duke of Richmond

in the English Peerage, in 1623. He was one of the noblemen and barons who

entered into a bond at Aberdeen, in March, 1592, for the security of

religion, and against the Popish Lords. It is unnecessary to pursue any

further the fortunes of the Lennox family, for they became merged in the

honours of the Dukes of Richmond, and lost their connection with the

important events of Scottish history. This narrative of an ancient Scottish

family, for which the author is chiefly indebted to the Scottish Nation,

will, it is believed, interest those who visit the shores of the Gareloch,

where those estates of the Lords of Lennox were situated, from whence came

their early territorial distinction.

In addition to the large

holdings of the Lennox family, details of which have been given and will

follow further on the following extract from Irving's history of the county

will show what a great extent of territory once was comprised within their

estate:—"Leaving the barony of Colquhoun, and passing the beautiful property

of Glenarbuck, laid out by Gilbert Hamilton, Lord Provost of Glasgow, and

since in the possession of different gentlemen, we enter what may be termed

the church lands of Kilpatrick, gifted by the pious munificence of the early

Earls of Lennox to the Abbey of Paisley. Some time about the end of the

twelfth century, Alwyn, the second Earl of Lennox, confirmed to the Church

of Kilpatrick a gift of the lands of Cochno, Edinbarnet, Cragentulach,

Monachkeneran, Dunteglenan, Cultbuic, and others, and added thereto a grant

of his own of the Iands of Cateconon, for the weal of the soul of his

sovereign, Alexander II., of his own, and of all his race. In attaching

these lands to the Church of Kilpatrick, the donor seems to have freed them

from all burdens; for when Earl David, the brother of William the Lion, who

held the superiority of the Earldom during the minority of Alwyn's

successor, attempted to derive aid from them, as from his other lands, the

holders resisted, and he was compelled to depart from his intention. The

various possessions appear at this time to have been held, on behalf of the

church, by a person named Bede Ferdan, who lived at Monachkeneran, in the

great house built of twigs, domo magna fabricata de virgit, and who, with

other three individuals, was bound to receive and entertain all pilgrims

repairing to the Church of St. Patrick. The lands conferred upon the Church

of Kilpatrick formed in after years a fertile subject of dispute, and in one

of the feuds which ensued, Bede Ferdan, above referred to, was slain in

defending what he considered the rights of the Church. The dispute regarding

the church lands originated in the following manner. Earl Maldowen, Alwy n's

successor, out of the love he entertained for the monks of Paisley, in whose

abbey he had chosen his place of sepulture, granted to them the Church of

Kilpatrick and all the lands attached thereto. Maldowen's brother, Dugald,

was at this time rector of Kilpatrick, and resisted the right of the monks

to those lands which they claimed as ancient pertinents of the Church, and

as confirmed to them directly by various charters. The case was tried by

papal delegates in 1233, and the proceedings, as recorded in the Register of

Paisley, give a clear and remarkable insight into our early ecclesiastical

polity. Dugald, in the end, was compelled to yield. The Church, as in 1227,

was decreed to belong to the Abbey of Paisley, in propriis uses, and the

vicarage was taxed at twelve merks of the alterage, or the tithe of corn, if

the alterage was not sufficient. The procurationes due to the bishop were at

that time taxed at one reception (hospitium) yearly. The Abbot of Paisley,

out of consideration for Dugald, who had thrown himself upon the mercy of

the monastery, allowed him to retain the rectorship for his lifetime, and in

addition thereto granted him half a carucate of the lands of Cochno. Still

the dispute, though decided upon by the papal delegates, was far from being

terminated, and the Abbot was more than once obliged to bestow a money

equivalent upon those who held land in Kilpatrick, which the monks alleged

had been gifted to the monastery. Thus Gilbert, the son of Samuel of

Renfrew, obtained sixty silver merks on resigning the lands of Monachkeneran-and

Malcolm, the son of Earl Maldowen, received a similar sum, pro bona pacis,

on resigning to the monastery the lands of Cochno, Finbelach, and Edinbarnet.

About the year 1270, new claimants came forward for the Church lands of

Kilpatrick in the person of John de Wardroba, Bernard de Erth, and Norrinus

de Monnargand; and in consideration of their title through their wives,

grandnieces and heiresses of Dugald the rector, the Abbot paid them 140

merks, and obtained a charter of resignation from each. Three years

afterwards Malcom, Earl of Lennox, "before he received the honour of

Knighthood," confirmed to the Abbot and monastery of Paisley all the lands

which they held in Lennox, including not only those which belonged to the

Church of Kilpatrick, but also Drumfower (Duntocher), Renfede, and

Drumdynanis, which had been given by his predecessors to the monastery

itself. Yet even before the close of the century Robert, Bishop of Glasgow,

had to inhibit the Earl's steward, Walter Spreull, and at length the Earl

himself, from making a new claim to these lands in a secular court."

The long-descended race, the

Colquhouns of Luss, have held lands in the county of Dunbarton as far back

as the time of Alexander II., when Umphredus de Kilpatrick obtained a grant

of the barony of Colquhoun, and in conformity with custom, assumed the name

of his territorial possession. The barony was in the parish of Kilpatrick,

and upon a prominent point, the rock of Dunglas, near Bowling, the new

proprietor erected a stronghold whose ruins still exist in picturesque

decay. Sir Robert Colquhoun, the grandson of the above Umphredus, married

the heiress of Luss and became the founder of this ancient family, being

succeeded by his son, Sir Humphrey, whose name appears as witness to

charters granted by the Earls of Lennox in 1390, 1394, and 1395. His son,

Sir John, was governor of Dunbarton Castle during the minority of James II.,

was slain by a body of Highlanders in 1440, and was succeeded by his

grandson, also Sir John, who was Sheriff of Dumbartonshire in 1471. In 1474,

he was raised to the dignity of Grand Chamberlain, and was appointed one of

the special ambassadors to London, to treat of a marriage between two young

members of the royal family of England and Scotland. The King was so much

pleased with Sir John in this delicate mission that he made him governor of

Dunbarton Castle for life. This was in September 1477, and the next year

this brave soldier was killed by a cannon ball at the siege of the Castle of

Dunbar.

Sir Humphrey, who succeeded,

received in 1480 a remission from the Crown for the relief duties of his

lands, in consideration of his father, Sir John, having fallen at Dunbar.

Sir Humphrey, who was twice married, first to a daughter of Lord Erskine,

secondly to a daughter of Lord Somerville, died in 1493, and was succeeded

by his son Sir John, who married into the family of the Darnley Earls of

Lennox, thus acquiring the life-rent of some lands of Glenfruin. Sir John

also acquired various properties in the Gareloch district, Lettrowalt and

Stuckinduff, Finnart, Portincaple, and Rachane. As illustrating some of the

local feuds of the period it may be told that, in February 1514, Sir John

Colquhoun obtained a summons for ,pulzie against Robert Dennistoun of

Colgrain for having harried the Mains of Luss and the mailing of Dumfyn, of

certain kye, horses, and sheep, all duly specified and appraised in the

summons. His son Humphrey succeeded in 1536, and left a family, of whom the

eldest, Sir John, succeeded his father in 1540, and married a daughter of

Lord Boyd. Sir John, in 1568, had a remission from the Regent Murray for his

absence from the muster at Maxwellheugh. Sir Humphrey succeeded his father

in 1575, and left three daughters at his death. He purchased from Robert

Graham of Knockbain the coronatorship of the county of Dunbarton, to be held

blench of the Crown, for one penny. During one of the feuds which distracted

the Lennox country, he was said to have taken refuge in his old Castle of

Bannachra, where the treachery of a servant in lighting him up one of the

stairs, made him a mark for the arrows of his pursuers, who had sought him

in this retreat, and he was killed. [Dr. Macleay, in his memoirs of Rob Roy,

gives a different account of the death of the laird of Luss, in which, also,

he erroneously alludes to him as having fought the battle of Glenfruin. He

says, "Colquhoun of Luss, having been at a great party in Edinburgh, had

grossly insulted the Countess of liar. About this same time the laird of

Macfarlane, whose lands lay about the north end of Loch Lomond, had, in a

foray to the Leven, killed five gentlemen of the name of Buchanan, for which

he fled and concealed himself in Athol. He there met Lady liar, who, anxious

to revenge the affront formerly given her by the laird of Luss, promised to

obtain Macfarlane's pardon if he would despatch Colquhoun. Macfarlane

accordingly set off, collected a few of his people, and went by water to

Rossdou. He was noticed by Colquhoun, who fled to Bannachra, at a short

distance, and concealed himself in a vault. Macfarlane followed, dragging

him from his hiding place, and murdered him. It is said his blood still

stains the floor in which the deed was perpetrated."] Sir Alexander

Colquhoun succeeded in 1592 on the assassination of his brother. The

principal event in his life was the fatal conflict in Glenfruin between the

Colquhouns and the MacGregors in 1603, which will be described elsewhere. He

married, in 1595, Helen, daughter of Buchanan of that ilk, and left a Iarge

family. Sir John Colquhoun succeeded, and in 1620 he married Lady Lilias,

eldest daughter of the fourth Earl of Montrose, and five years afterwards,

was created a Nova Scotia baronet. Criminal proceedings were instituted

against Sir John for absconding with the sister of his wife, who had taken

up her abode at Rossdhu, after her father's death. He therefore fled the

country, and after a time his brother completed an arrangement with the

numerous creditors against the estate. Charters were taken out, by which Sir

John's eldest son was infeft of the lands in 1647. Sir John was

excommunicated by the Presbytery of Luss for his crime; and though he made

confession and sought to be reponed, still the sentence was not withdrawn.

Sir John CoIquhoun, son of

the preceding, succeeded, and was a zealous adherent of the Royalist party

in Scotland, on whose behalf he endured many hardships. Cromwell inflicted a

fine of £2000 upon him, subsequently reduced to £666 13s. 4d. He purchased

Balloch in 1652 from James, Duke of Lennox, and, by his marriage with

Margaret Baillie, acquired the barony of Lochend in Haddingtonshire. As Sir

John died without leaving male issue, the estates devolved upon his eldest

brother, Sir James, who married Pennel, daughter of William Cunningham of

Ballichen, Ireland. Among the Luss papers there is a "Protection," given to

him by General Monk in 1655 "to pass with his traveyling traines to London,

or other parts in England, and to repair into Scotland without molestation."

His son, Sir Humphrey, was one of the representatives for Dunbartonshire in

the last Scottish Parliament, and a determined opponent of the Union between

England and Scotland. He married Margaret, daughter of Houston of Houston,

and had issue a daughter, Anne. In December 1706 Sir Humphrey executed a

deed entailing the estate of Luss on his only daughter, and her husband

James, son of Ludovick Grant of Grant, and the heirs of the marriage, whom

failing, to the heirs male whatsoever of Sir Humphrey. He died in 1718, and

was succeeded by his son-in-law, James Grant, who thereupon assumed the name

and arms of Sir James Colquhoun of Luss. On his succeeding to the fine

estate of Grant, in terms of Sir Humphrey's will, the estate of Luss

devolved upon a younger brother Ludovick, who thereupon assumed the name and

arms of Sir Ludovick Colquhoun of Luss. He also - succeeded to the Grant

estate, when Luss devolved upon the next brother James, who assumed the name

and arms of Sir James Colquhoun of Luss. A dispute being likely to arise

with the Tullichewan branch of the family regarding the old patent of

baronetcy, Sir James was created a baronet of Great Britain in I786. He

married Lady Helen, daughter of William, Lord Strathnaver of the family of

Earls of Sutherland. In his lifetime the town of Helensburgh was founded,

and so named in honour of his wife Lady Helen. Dying in 1786, he was

succeeded by his son Sir James, who was Sheriff-Depute of Dunbartonshire,

and a principal Clerk of Session, and dying in 1805 was succeeded by his son

James, son of Jane—daughter and co-heiress of James Falconer of Monktown.

Sir James was, in 1802, elected member of Parliament for Dunbartonshire, and

in 1799 married Janet, only surviving daughter, by his first marriage, of

Sir John Sinclair, Bart., of Ulbster, the distinguished Scottish patriot.

Lady Colquhoun was a lady of great discernment, and of genuine Christian

philanthropy, and lived till October 1846. Sir James died in 1836,—leaving

three sons,—James who succeeded, and John who married in 1834 Miss Fuller

Maitland, and had a large family, amongst them Colonel Alan John Colquhoun,

who is heir presumptive to his cousin, the present Sir James. John Colquhoun

was a man of fine character, a single-hearted, God-fearing gentleman, whose

works, the Moor and the Loch, and the Rod and the Gun, have had a wide

circulation. He was born in 1805, and entered the army, first joining the

33rd Regiment, and subsequently the 4th Dragoon Guards. When he left the

army, John Colquhoun settled in Edinburgh, where his family were educated,

and for a great number of years, until his death in 1885, he conducted

evangelistic meetings in the Grassmarket. Possessed of a beautiful

simplicity of character, gentle and kindly, as a true soldier of the Cross,

there was something in the manly bearing and unaffected urbanity of John

Colquhoun which gained him affectionate respect. A prayer of his is

recorded, in which he dedicated himself to the service of his Heavenly

Father, and rested all his hopes on the merits of a crucified Saviour. A

keen observer and lover of nature, while following the wild animals and

birds, whose ways and haunts he so graphically described in his books, he

charms his readers with the picturesqueness of his narrative. His

observations upon the habits and ways of both large and small game, and his

accuracy of detail, have gained for his writings a lasting popularity.

Tenderly loved by an attached and united family, and esteemed by a wide

circle of friends, John Colquhoun passed away in all the strong yet humble

assurance of a devout Christian. Another of the family, William, was well

known and respected, and lived the greater part of his life at Rossdhu, with

his brother, the late Sir James Colquhoun.

Sir James Colquhoun of Luss,

who succeeded in 1836, was a man of upright character and unswerving

integrity, modest and unassuming in demeanour, who lived and died among his

own people. He was an excellent landlord, and did a great deal for his

extensive estates, rebuilding almost every farm steading, and many of the

cottages. He planted hundreds of acres, and ornamented the policies of

Rossdhu by transplanting there great numbers of large trees. Many of these

trees thus transplanted were from fifty to sixty years growth, and, in

nearly every case, they succeeded. Sir James laid out large sums on

drainage, land reclamation, and other improvements. He took a keen interest

in agricultural matters, and frequently presided at meetings of agricultural

societies. He was a strong Liberal in politics, and represented the county

for some years in parliament, but be never took much part in parliamentary

proceedings. When the rifle volunteer movement first started in 1859, Sir

James took it up warmly, and raised a local corps of riflemen from his own

estates. He was an ardent supporter of the Church of Scotland, and held

firmly to its standards, including strong views upon the Sabbath observance

question. In 1859 he resolved to enforce his rights as a landlord in

striving to protect the pier at Garelochhead from being made use of by the

notorious Sunday steamer, his servants forcibly resisted the landing of

passengers, and he carried the case to the Court of Session in Edinburgh. He

successfully contended that, as the pier was erected on his own private

grounds, and was not a public pier, he had perfect right to make his own

regulations for the traffic.

Sir James took a deep

interest in Helensburgh, and his measures helped the rising prosperity of

the burgh. Any scheme for assisting the water supply, for providing

recreation grounds, for municipal improvements, for opening up new roads,

was sure of his liberal support. He was a man of sincere and unostentatious

piety, but of a most reserved and diffident bearing among strangers, and he

cared nothing for the fashionable and social gatherings of the world.

Consequently he was rarely seen outside of his own estate, though he was

invariably affable and courteous in his circle of familiar friends. His sad

death by drowning, in December 1873, caused a great shock in Helensburgh and

throughout the Luss estates, where he was well known and beloved.

Accompanied by his brother William, Sir James, and four of his servants, had

been for some hours deer stalking on Inch Lonaig, one of the islands in Loch

Lomond. Returning home with the heavily laden boat, a violent storm arose as

they were half way between the island and the shore, and as it was getting

dusk, Mr. William Colquhoun, who was rowing in a small boat by himself,

suddenly lost sight of the party in a blinding storm. When the gust had

blown over, Sir James' boat could not be seen, and, after a long search, it

was evident that the stormy waters had engulfed the entire party. The bodies

of Sir James and two of his men were found after some days search, and the

tragic event was long mourned throughout the neighbourhood of Loch Lomond,

for, in the chief of the Colquhouns, the poor lost a generous friend, and

his tenantry and dependents a just and liberal landlord.

His son and successor, the

present Sir James Colquhoun, inherits his father's character for

uprightness, and a desire to forward all measures of usefulness. His

singularly modest and retiring disposition prevents him from entering into

public life, but his cultured mind and natural sagacity well qualify him for

fulfilling the duties of his position. Owing to the peculiar mariner in

which the great Luss estates are now placed, being managed by Trustees, Sir

James has not the power to carry out further improvements, or to spend large

sums in developing the property. Delicacy of health also obliges him to live

much in the South of England, but being Lord Lieutenant of Dumbartonshire,

he resides part of the year at Rossdhu, and gives scrupulous attention to

the duties of his high office. Sir James is characterised by a deep vein of

religious fervour, and his published works testify to the evangelical nature

of his views upon sacred subjects. Sir James was married in 1875 to

Charlotte Mary Douglas, youngest daughter of the late Major William Munro,

of the 79th Cameron Highlanders, and grand-daughter of Sir Robert Abercromby,

Baronet, of Birkenbog, and has issue two daughters.

The lands and barony of

Colquhoun, from which the family derive their name, have passed into other

hands and lay on the south-east part of the county, mostly in the parish of

Old Kilpatrick. The woods of Colquhoun were often trodden by Robert the

Bruce, and in these woods in 1313 he, one day, encountered a carpenter of

the name of Roland who, by his timely information, saved the King from being

the victim of a stratagem of Sir John Menteith of Rusky, who was about to

betray him to the English. On 30th June, 1541, James V., by letters tinder

the Privy Sea], granted to John Colquhoun of Luss the duties of the lands

and barony of Luss, with the castle, tower and fortalice of Rossdhu, and the

lands and "barony of Culquhone," with the manor-place of Dunglass. The old

ruin of Dunglass Castle, so picturesquely situated on a headland of the

Clyde near Bowlines, was said to have been built in 1380, and was one of the

residences of Sir John Colquhoun, Chamberlain of Scotland in 1439, and long

continued to be occupied by the family. It used to be of strong military

importance, and was garrisoned by the Covenanters to protect themselves

against the Marquis of Montrose. General David Leslie, commander in chief of

the army of the Committee of Estates, issued his orders in December? 1650,

for garrisoning the "House of Dunglas." In 1735 the Commissioners of Supply

"recommended some of the free stories out of the old ruinous house of

Dunglas, to be used in repairing the quay." At that time it was possessed by

the Edmonstones of Duntreath, but has since formed part of the estate of

Buchanan of Auchintorlie. The present mansion house, which immediately

adjoins the castle, was built by Sir Humphrey Colquhoun, who was

treacherously slain by an arrow at his Castle of Bannachra in 1592.

Henry Bell may almost be said

to rank with George Stephenson, as a discoverer of the great capabilities of

steam, as a motive power, in propelling ships through the water. He was born

at the village of Torphichen, in Linlithgowshire, on 7th April, 1766, and

was descended from a race of mechanics who, for generations, were known as

practical mill wrights and builders, and had been engaged in many public

works. After being educated in the parish school, Henry Bell, in 1780, began

to learn the trade of a stone mason. Three years afterwards he became an

apprentice to his uncle, who was a mill-wright, and on the termination of

his agreement, he went to Borrowstounness to learn ship modelling. In 1787

he worked with Mr. James Inglis, engineer, with the view of completing his

knowledge of mechanics. From there he went to London, where he was employed

by the celebrated Mr. Rennie, and had opportunity of gaining a practical

acquaintance with the higher branches of his art. About the year 1790 he

returned to Scotland, and is said to have set up as a house carpenter in

Glasgow; his name appears, in October 1797, as a member of the Corporation

of Wrights in that city. He had ambitious designs in Glasgow, and strove to

undertake public works but, from a deficiency of means, or from want of

steady application, he never succeeded. One who knew Bell at this time wrote

thus of him: "The truth is, Bell had many of the features of the

enthusiastic prospector; never calculated means to ends, or looked much

farther than the first stages or movements of any scheme. His mind was a

chaos of extraordinary projects, the most of which, from his want of

accurate, scientific, calculation, he never could carry fully into practice.

Owing to an imperfection in even his mechanical skill, he scarcely ever made

one part of a model suit the rest, so that many designs, after a great deal

of pains and expense were successively abandoned. He was, in short, the hero

of a thousand blunders and one success."

The idea of propelling

vessels by means of steam early took possession of Henry Bell, and

ultimately he brought his ingenious scheme into practice. Towards the close

of last century, the Fly-boats, as they were termed, formed the principal

means of communication on the Clyde, between Glasgow and Greenock. These

boats were constructed by Mr. William Nicol of Greenock, well known as an

excellent builder of ships boats for many years. They were about 28 feet

keel, about 8 feet beam, 8 tons burden, and wherry rigged. A slight deck, or

awning, was erected abaft the main-mast so as to cover in the passengers,

who were accommodated on longitudinal benches. Some of them, on a more

improved principle, had a contrivance by which part of the deck or awning

might be lifted up on hinges, to allow the passengers in fine weather more

freedom in enjoying the voyage. A kind of platform ran along the edge of the

deck, outside, to allow those navigating the boat to pass from the bow to

the stern, where the steersman sat, without troubling the passengers! The

boats generally left Greenock with a flowing tide if possible; if the wind

was favourable, a passage of four or five hours to Glasgow was considered a

great achievement. When the wind and tide were adverse, then it was toilsome

work, and the passengers and crew were glad to get out at Dunglas, and wait

there for some hours, enjoying a ramble through the picturesque woods and

crags in the neighbourhood.

These boats which, to the

present generation, may well seem a slow and wearisome mode of progression,

were still an improvement upon the packet boats, or wherries, in vogue till

then. One of the owners of the boats was Andrew Rennie, town drummer of

Greenock, but a man of considerable ingenuity and speculation, and he

proposed to his partners to have one built on a different model to be

propelled by wheels. Accordingly he got a boat constructed of a greater

breadth of beam, to the sides of which he affixed two paddle wheels, to be

worked by manual labour. This boat, which came to be known as "Rennie's

wheel boat," after making several trips to the Broomielaw, was sold, as it

was not found to be any saving of labour to those who propelled it. Henry

Bell heard of this plan of the wheel on the boat's side, and applied to Mr.

Nicol to build for him a boat about 15 feet keel, with a well, or opening,

in the "run," in which he placed a wheel, to be worked by manuaI-power.

Finding this single wheel not to answer the purpose intended, he got Mr.

Nicol to close up the well, and tried his boat with two wheels, one on each

side. He was convinced, after trial, that this was the true way of

distributing the propelling power, though of course being wrought by manual

labour no great speed could be attained. Hence it was that, after long

consideration, he came to the conclusion that, if he could apply steam power

to his wheel, the deficiency in propelling power would be amply made up.

Another inventive genius, Symington of Greenock, had caused a canal boat to

be fitted up with a steam engine, with a brick funnel, which was actually

employed on the Forth and Clyde canal in towing vessels, but he did not

succeed in adapting steam to the propulsion of boats in open waters.

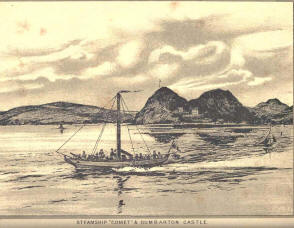

Henry Bell now resolved to

prosecute his steamboat scheme, and induced Messrs. John & Charles Wood of

Port-Glasgow, to lay down the keel of the first STEAMBOAT in their building

yard in October, 1811: this was the celebrated Comet, and she was launched

in June, 1812, being called after the great meteor of the preceding year.

The Comet was a wooden boat of 42 feet long, 11 broad, and 5½ deep, and 25

tons burden, and was fitted with the long funnel of the early steamers,

which did duty for a mast as well. John Robertson of Glasgow made the

engine, which was a condensing one of 3 horse power, the crank working below

the cylinder, the engine shaft of cast iron, a fly wheel being added to

equalise the motion. Originally the vessel was fitted with two pair of

paddle wheels, 7 feet in diameter, with spur wheels 3 feet in diameter; so

that by means of another spur wheel, placed between these, and geared into

them, each pair of paddles rotated at the same speed. However, this

arrangement was found to be very inefficient, as one pair of paddles worked

in the wash of the other, and there was a loss of power in working through

toothed wheels. N r. Robertson, the engineer, tried to dissuade Henry Bell

from planning his paddles in this manner, but the latter insisted on trying

the experiment, which was not successful. The double wheels were then

removed, and Robertson made another engine of 4 horse power, the cylinder 12

inches in diameter. The workshop where this engine was made was in Dempster

Street, North Frederick Street, Glasgow; it was a vertical engine. The

original model of the Comet is in the possession of Messrs. John Reid & Co.

of Port-Glasgow. The boiler of this historic vessel was made by David Napier

of Camlachie. [Messrs. Bell and Robertson had seen Symington's boat in the

canal, and had discussed the practicability of propelling vessels by

machinery. The latter had manufactured a small engine on speculation of

three horse power, and this Bell purchased for £165, an additional £27 being

promised to other parties for the boiler and fittings. After the success of

the venture was assured, the Comet was beached at Ilelensburgh and twenty

feet added to her length, an engine of six horse power being substituted.

Irving mentions, "the original engine was first sold to Archibald M`Lellan &

Sons, coachbuilders, who applied it to some of their machinery ; it

afterwards, by the intervention of the maker Robertson, passed into the

hands of Mr. Alexander, distiller, Greenock; it bad several other owners

after this, but ultimately fell into the possession of Messrs. Gird-wood &

Co., engineers, Glasgow, who exhibited it as a curiosity at one of the

meetings of the British Association in Glasgow."]

Thus was the first steamboat

completed, and it was announced in the Greenock Advertiser of 15th August,

1812, that the COMET would make the passage three times a week between

Glasgow, Greenock, and Helensburgh, by the power of "wind, air, and steam."

The interest this created was widespread and intense, great crowds of people

lined the shores from the Broomielaw downwards to witness her departure and

arrival, but of those who gazed on the novel spectacle few realised to

themselves the immense revolution which was thus being brought about in the

annals of maritime enterprise. Few believed in the ultimate success of the

venture, and Bell was looked upon as an enthusiast, while many were even

afraid to set foot in his vessel. A traveller, in 1815, records that he

sailed in the Comet from Glasgow to Greenock, leaving in the morning, and

arriving at Greenock after seven hours passage, three of which, however, had

been spent lying on a sandbank at Erskine. Soon after the success of Henry

Bell's steamer, the next vessel worked by this novel power was the

Elizabeth, of 33 tons burden, 58 feet long, and she also was built by John

Wood. But so little apprehension was caused by the advent of the steamboats

that wherries were regularly announced to sail from Greenock to Helensburgh

and the Gareloch in opposition to the steamers.

It was years before this

successful effort at steam navigation that Bell conceived the idea of

propelling vessels by other agency than the power of wind. He thus wrote in

1800, "I applied to Lord Melville on purpose to show his lordship and other

members of the Admiralty, the practicability and great utility of applying

steam to the propelling of vessels against winds and tides, and every

obstruction on rivers and seas where there was depth of water." Disappointed

in this application he repeated the attempt in 1803, with the same result,

notwithstanding the emphatic declaration of Lord Nelson, who, addressing

their lordships on the occasion, said, "My Lords, if you do not adopt Mr.

Bell's scheme other nations will, and in the end vex every vein of this

empire. It will succeed, and you should encourage Mr. Bell." Failing in this

country, Bell tried to induce the naval authorities in Europe as well as the

United States government to adopt his plan ; he succeeded with the

Americans, who were the first to put his scheme into practice, and were

followed by other nations.

After his great achievement

in successfully navigating the waters of the Clyde by the power of steam,

Bell, who had settled in Helens-burgh, continued to prosecute his business

of builder and wright. He also embarked upon more speculations in connection

with efforts to establish other passenger steamers, but did not make any

great success, for }e was ever possessed by a restless desire to try new

experiments. He originated various improvements in Helensburgb, of which

town he was the first Provost, serving from 1807 till 1810. Latterly he had

the management of the Baths Hotel, assisted by his industrious wife, and

there be died in November 1830. Efforts were made by his friends to induce

the government to award a sum of money to one who had done so much to open

up the way to our vast international carrying trade, and whose genius had

paved the road for an entire revolution in the navigation of the ocean. But

all they could succeed in getting was a paltry dole of £200, as will be seen

from the following pathetic letter, written to one who had interested

himself in the matter:

"BATHS, HELENSBURGH, 19th June,

1829.

"My DEAR F1UEND,—I write

these few lines lyeing on my bed unable to sit up. But the letter you sent

me with the remittance of £200 from the Treasury, a gift ordered by the late

Mr. Canning, will relieve my mind a little, and enable me to get Mrs. Bell's

house finished, and to pay the tradesmen. I was afraid I should not have got

this £200, little as it is. The wounds in my legs are rather easier during

the last few days, owing to my keeping close to my bed. I will write to you

in a day or two more fully.

I am, your old friend,

"HENRY BELL.

"Mr. E. MORRIS, London."

For a few years be had

enjoyed a pension of £100 a year from the Clyde Trust, for although he had

been the pioneer of vast improvements to navigation and commerce, be had

reaped none of the rewards of his inventive genius. His funeral took place

on the 19th November, when a large company of mourners followed the body of

the man who had done so much for steam navigation to its last resting place

in the churchyard of Row. In 1839 a stone obelisk in memory of Henry Bell

was erected on the highest point of the rock, beside the old castle of

Dunglass, just overlooking the scene where his first triumph was gained.

The late Robert Napier of

Shandon, who knew well how much his friend. Henry Bell had laboured for the

triumph of steam navigation, placed a fine sitting statue of him in Row

Churchyard. The expression of the face is well rendered, and gives a good

idea of the man, as he was in his later years, which were much clouded with

disappointment. A very handsome granite obelisk in memory of Bell also

stands in a conspicuous position on the sea esplanade at the foot of James

Street, Helensburgh, chiefly erected through the public spirit of the late

Sir James Colquhoun and Robert Napier. On the pedestal is the following

inscription:—

ERECTED IN 1872

TO THE MEMORY OF

HENRY BELL,

THE FIRST IN GREAT BRITAIN WHO WAS

SUCCESSFUL IN PRACTICALLY APPLYING STEAM

POWER FOR THE PURPOSES OF NAVIGATION.

BORN IN THE COUNTY OF LINLITHGOW IN 1766.

DIED AT HELENSBURGH 1830.

The following is a copy of

the advertisement of the first passenger steamboat which plied on the waters

of the Clyde:-

"Steam Passage-boat THE

COMET, between Glasgow, Greenock, and Helensburgh, for passengers only.

"The Subscriber having, at

much expense, fitted up a handsome vessel to ply upon the River Clyde,

between Glasgow and Greenock, to sail by the power of wind, air and steam,

he intends that the vessel shall leave the Broomielaw on Tuesdays,

Thursdays, and Saturdays, about mid-day, or at such hour thereafter as may

answer from the state of the tide—and to leave Greenock on Mondays,

Wednesdays, and Fridays, in the morning, to suit the tide. The elegance,

comfort, safety, and speed of this vessel require only to be proved, to meet

the approbation of the public; and the proprietor is determined to do

everything in his power to merit public encouragement. The terms are for the

present fixed at 4s. for the best cabin, and 3s. the second; but beyond

these rates nothing is to be allowed to servants or any other person

employed about the vessel. The subscriber continues his establishment at

Helensburgh Baths, the same as for years past, and a vessel will be in

readiness to convey passengers in the Comet from Greenock to Heleusburgh.

Passengers by the Comet will receive information of the hours of sailing by

applying at Mr. Houston's Office, Broomielaw; or Mr. Thomas Blackney's, East

Quay Head, Greenock.

"HENRY BELL.

"Helensburgh, 5th August,

1812."

For some years the Comet

continued to ply on her original route, and also for a short period on the

Firth of Forth, and subsequently she traded between Glasgow and Fort

William, via the Crinan Canal. On the 7th of December, 1820, she started on

her return journey, but on the 12th, at Salachan, the vessel struck on a

rock, and had to be beached to enable the necessary repairs to be made. On

the 14th the run to Glasgow was resumed, and on the 15th was at Oban,

although by that time water was beginning to enter the vessel. On that day

the Comet left Oban for Crinan, during a violent snowstorm, and shortly

afterwards was driven, near the Dorus Mohr, by the force of the waves and

wind on to the rugged point of Craignish, where she parted in two,

amidships, at the exact spot where she had been lengthened in 1818. Henry

Bell, the owner of the Comet was on board, but he, along with all the crew

and passengers, were safely landed. After the unhappy striking of the vessel

the afterpart drifted out to sea, and the forward part sunk in deep water.

The engines, however, were saved, and incorporated in the machinery of the

second Comet of 94 tons, built by James Lang of the Dockyard, Dunbarton, in

1821, which had one engine of 25 horse power. This vessel also was lost off

Kempoch Point, Gourock, on 21st October, 1825, by coming into a collision

with a steamer, the Ayr, when a lamentable loss of life occurred.

Such was the fate of the

little vessel whose success inaugurated a new era in our mercantile marine,

with results of wonderful magnitude to all the nations of the world. It is

melancholy to reflect bow little was done to smooth the closing years of the

man to whose ingenuity and perseverance so much of the triumph of steam

navigation was due. With almost prophetic foresight Henry Bell thus spoke in

1812, when the little Comet first sailed on the Clyde. "Wherever there is a

river of four feet in depth of water through the world, there will speedily

be a steamboat. They will go over the seas to Egypt, to India, to China, to

America, Canada, Australia, everywhere, and they will never be forgotten

among the nations." No doubt there were not wanting those who sought to take

away from Bell the distinction of having been the first to apply steam to

the propelling of vessels, and Fulton, the American, has claimed the honour.

Dr. Cleland, the Annalist of Glasgow, writes on this subject. "It was not,

however, till the beginning of 1812 that steam was successfully applied to

vessels in Europe, as an auxiliary to trade. At that period, Mr. Henry Bell,

an ingenious, self-taught engineer, and citizen of Glasgow, fitted up, or it

may be said without the hazard of impropriety, invented the steam-propelling

system, and applied it to his boat the Comet, for, as yet, he knew nothing

of the principles which must have been so successfully followed out by Mr.

Fulton."

Morris, the friend of Henry

Bell, who wrote the only life of the inventor which has ever been published,

a brief and unassuming memoir, gives the following memorandum regarding

Bell's claims to be the first who introduced steam power, which was drawn up

by some of the early Clyde engineers.

"Glasgow, 2nd April, 1825.

"We, the undersigned

engineers in Glasgow, having been employed for some time past in making

machines for steam vessels on the Clyde, certify that the principles of the

machinery and paddles used by Henry Bell in his steamboat the Comet, in

1812, have undergone little or no alteration, notwithstanding several

attempts of ingenious persons to improve them. Signed by Hugh and Robert

Baird, John Neilson, David and Robert Napier, David M'Arthur, Claud Girdwood

& Co., Murdoch & Cross, William M'Andrew, William Watson."

The following appreciative

sketch of Henry Bell appeared in the modest Helensburgh Guide, originally

published by the late Mr. William Battrum more than thirty years ago, and

now out of print. "In person Mr. Bell was about middle size, a stout built

fresh complexioned man, hearty and genial in his manner. His features were

regular and expressive, impressing a stranger at a glance with a good

opinion of him as a shrewd, pawky Scot, an impression which ten minutes

conversation stamped as sound. His general knowledge was extensive, and be

had a peculiar aptitude for seizing the salient points of any new invention,

and making himself master of the subject. He was a great talker, when

excited by any favourite hobby, and nothing delighted him more than an

intelligent listener, to whom he would descant all night on any of his

multifarious plans and schemes. There were always some leading projects in

view. The construction of a canal betwixt east and west Tarbet, in Lochfine,

was a favourite one. He had also a scheme for the partial drainage of Loch

Lomond, and reclamation of the land, about which he had an extensive

correspondence with the Duke of Montrose, who did not receive it favourably.

The introduction of water to Helensburgh from Glenfruin, be had also in

view. The reclamation of waste lands in Scotland, and even the Suez Canal he

discussed, and urged its practicability, despite the opinion of many eminent

engineers. Of all his plans he was exceedingly sanguine; neither the

indifference of others, the want of resources, partial failure, or any of

the thousand embarrassments that haunt projectors, daunted him. Whatever the

failure or disappointment met, he was always hopeful of ultimate success.

With a large measure of Watt's inventive faculty, he possessed in a good

degree the energy and knowledge of men which Watt's partner, Boulton,

enjoyed. To the many doubts and disbelief of scientific and unscientific men

that steam vessels would never accomplish much, Bell's reply was always,

'they will yet traverse the ocean,' and his prophecy, now being fulfilled,

living men who heard it will verify."

Any description of the

Gareloch would be incomplete which did not give some account of the eminent

Robert Napier, who so long resided at his beautiful seat at West Shandon,

where his refined taste displayed itself in the accumulated treasures of art

he had gathered under his roof, and which he delighted to shew to his

friends. He was born at Dunbarton on the 18th June, 1791, being of a family

that, for several generations, had resided in the Vale of Leven, now so

noted for its Turkey Red dye works. His father, James Napier, was a burgess

of the town, and carried on the business of a blacksmith and mill-wright,

and his position in the town enabled him to give his son Robert a good

practical education in the Grammar School of Dunbarton. Here, in addition to

Classics, Mathematics, French, and other branches, he was taught landscape

drawing, and afterwards architectural drawing, by a Mr. Trail, a man of

taste and culture. The latter was on friendly terms with the Napier family,

and fostered young Robert's turn for things artistic. At the age of fifteen,

his father took him from school to College, but Robert's brain, even at that

early age, was full of mechanical ideas. Apprenticed to his father, he was

engaged in smith work till he was twenty years of age, when he entered the

office of the eminent lighthouse engineer, Robert Stevenson of Edinburgh,

who constructed the Bell Rock lighthouse. On returning to his native town,

his father wished Robert to enter into partnership, but the young man had

ideas of his own, which were much in advance of the humble, though

honourable, trade of a blacksmith. Accordingly, in 1815, he started in the

Greyfriars Wynd in Glasgow, as engineer and blacksmith, no doubt having in

view the future development of marine architecture. At first, orders came in

slowly, although he only worked with the aid of two apprentices. In

December, 1818, he married his cousin, Isabella Napier, a lifelong and truly

happy union it proved. His father-in-law, John Napier, was a clever and

prosperous engineer in Dunbarton, carrying on an iron foundry as well, and

was among the first to employ steam power to drive machinery, which he used

in boring cannon for Government during the Peninsular War.

In 1821 Robert Napier, along

with his cousin David, entered upon the occupancy of the Camlachie foundry,

and they undertook several large contracts, one of them being the pipes

required by the Glasgow Water Company, when bringing the supply from the

upper reaches of the Clyde. Mr. Napier's first land engine was, twenty years

ago, in use in Mr. Boak's spinning factory in Dundee. The business grew

rapidly, and the firm was constantly employed constructing boilers and land

engines, until, at last, Robert Napier's cherished dream was realised when,

in 1823, he received an order for a marine engine to propel the small paddle

steamer Leven, plying between Glasgow and Dunbarton. So good was the engine

that it wore out no less than three different hulls of the vessel, and may

now be viewed at the base of the rock of Dunbarton Castle, where it was

erected by his two sons as a memorial of their father. Robert Napier was one

of the pioneers of steam engines for marine purposes, and he foresaw the

great revolution likely to ensue when the vast powers of steam should be

fully applied to the propulsion of ships. The idea had occurred to several

inventors, vIiller of Dalswinton, and William Symington, as far back as

1788, had endeavoured to enlist the steam engine as a propeller, and, in

1801, Symington built the Charlotte Dundas, for Lord Dundas, for towing

barges on the Forth and Clyde canal, but the vessel did not prove a success.

Trevithick, in 1805, was experimenting on the Thames with his engine for

propelling ships, but it was reserved for Henry Bell, in 1812, to construct

the Comet, which was successfully driven through the water by the power of

steam. The boiler and engine castings of this famous little vessel were made

by David Napier, the engines by John Robertson of Glasgow, and were

afterwards presented to South Kensington Museum by Robert Napier. Curiously

enough, the cylinder of the Comet, on the break up of the vessel, was placed

by Henry Bell on the top of the Baths Hotel at Helensburgh, where he

resided, and it did duty for many a long year as a chimney can.

In 1828 Mr. Napier's

increasing business necessitated his removal to the famous Vulcan Foundry,

and he added to it, in 1835, the larger engine works of Lancefield. So well

known had he become, that no shipping company of any standing could be

started without first seeking his advice and co-operation. In 1836 he began

his connection with the Honourable East India Company, and into one of their

steamers, the Bernice, was introduced by his manager, David Elder, variable

expansion valves in the engines. The British Queen followed in 1839, a

sister ship to the President, for the Atlantic trade. She was of 420 horse

power, and surface condensers for her engines were introduced after the

method of Samuel Hall of Aberdeen. About this time Mr. Napier built several

steam yachts for the well known sportsman, Mr. Assheton Smith, one of which,

the Tire King, of 700 tons, attained to the speed of 15 miles an hour, the

greatest of any vessel then afloat. This rate of speed was due to Mr.

Smith's foresight in building his vessel with fine hollow water lines,

instead of those believed to be the best, namely the "cod's head and the

mackerel tail," and it formed a distinct epoch in the formation of

steamships. In 1839 was started that great enterprise the Cunard Company,

when Mr., afterwards Sir Samuel Cunard, projected his Iine of steam ships

between New York and Liverpool. The first contract was with Robert Napier,

who was to furnish four steamers of 900 tons each, and 300 horse power. This

size of vessel Mr. Napier considered too small, and pressed Mr. Cunard to

increase it to 1200 tons and 400 horse power. Such was the commencement of

that remarkable departure in shipping known as the Cunard Company, and of

the original subscribers not one now survives. The Persia and the Scotia,

paddle wheel steamers, built by Mr. Napier for the Cunard Company, were

famous in their day. The Scotia consumed 160 tons of coal in 24 hours, and

could make the voyage from New York to Liverpool in 8 days 22 hours, whereas

it took the Britannia, in 1840, no less than 14 days 8 hours to cross the

ocean.

Robert Napier constructed

many ships of war for the British Government, famous amongst which was the

Black Prince, one of the finest war vessels in the navy, besides numerous

ironclad warships for others of the great European Powers. From first to

last his workmanship elicited the highest encomiums from the naval

authorities, and he was the first to throw open his yard to naval officers

who sought to gain practical information in the engineering branch of their

profession. Foreign governments also took advantage of his liberality in

this respect, and his name was an influential and honoured one in naval

circles throughout Europe. The last contract which he personally made was in

1865, when he undertook to build the Pereire and Ville de Paris, of the

French Transatlantic Mail Service, which, for speed and economy, surpassed

all the vessels then in the Atlantic trade. By this time he had amassed a

large fortune, and had many honours bestowed upon him, in recognition of the

eminent services which be had rendered to marine architecture. The honours

and decorations, crosses and medals, showered upon Mr. Napier had no effect

in altering the noble simplicity of character and manner which ever was

conspicuous in this distinguished man. He was practically the father of

steamship building, and all his work was characterised by the highest degree

of excellence, often to his own loss and detriment, for he allowed nothing

to leave his yard but what would bear the closest inspection. It was an

absolute guarantee of the highest order that a ship had been constructed by

Mr. Napier's firm, and his certificates were prized by those who received

them, as certain to lead to future promotion.

In his beautiful residence at

West Shandon the latter years of Mr. Napier's life were passed, after he had

retired from active business, and here he gathered together a very fine

collection of all sorts of objects of art, including paintings, statues,

china, and all varieties of ceramic ware, besides old armour, clocks,

watches, glass ornaments, and other curiosities. It was a great delight to

the courteous old man to go round with his visitors, and point out the rarer

gems of art treasures he possessed, and year by year he bad hosts of

visitors of all ranks, for his hospitality was on a lavish scale. The

collection contained many choice specimens, which, at its subsequent

dispersal in London, were acquired for some of the famous galleries and

museums of Europe; but the pleasure of seeing them at Shandon was

wonderfully enhanced by the presence of the genial but simple owner. He died

on 23rd June, 1876, and his funeral in Dunbarton Church, a few days

afterwards, was attended by a great assemblage of his friends, neighbours

and his workmen, as well as by men whose names are widely known and honoured

in the scientific world. |