|

The Clyde has the honourable distinction of being the

first European river on which the steamboat was used commercially.

Various attempts had been made from time to time by many ingenious

inventors to apply the steam-engine to propel vessels. Amongst the

earliest of these is the patent of Jonathan Hulls, in 1736, for a

tow-boat, having a rotatory paddle at the stern, driven by a steam

apparatus placed in the boat. It is said, however, that Denis Papin,

in 1707, invented a steamboat in which he ascended the river Weser.

The inhabitants on the banks, resenting this innovation on their

boating privileges, are said to have destroyed his vessel. Curiously

enough, since history is said to repeat itself, the same sudden

termination to another and like effort of applied science seems to

have taken place nearer home, as tradition says that the boatmen of

Loch Katrine were so indignant at the appearance of the first

steamer which was placed on this beautiful sheet of water that they

managed to sink her. These stories seem probable enough when we find

that the feeling at coast places was so strong against the

steamboats that they were not allowed to approach the quay, and it

is said that a steamer lying off one of the coast towns had her

cables cut, some of the old boatmen being of the belief that she was

aided by the powers of evil.

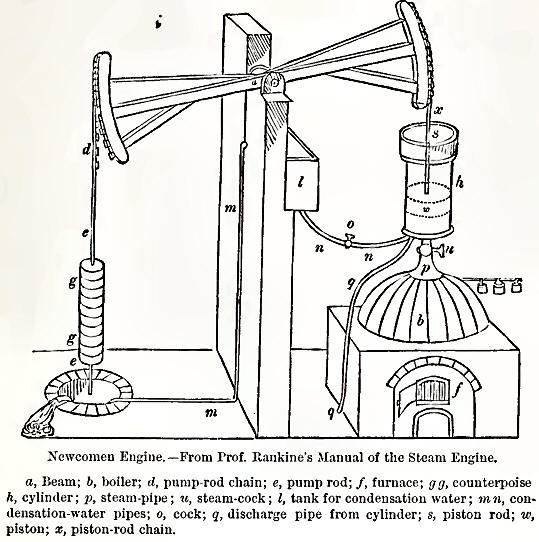

Papin, who appears to have been a very able man,

turned his attention, so far back as the year 1690, to improvements

in the cylinders of the rude steam appliances of his day, and it is

said that he conceived the idea of moving a piston in a cylinder by

the alternate action of the pressure and condensation of steam

effected in the cylinder,—the great improvement of Watt, in 1761,

was the condensation of the steam in a separate vessel called the

condenser, whereby the loss of power due to the alternate heating

and cooling of the cylinder, as in Newcomen’s engine, was overcome.

An important attempt to utilize steam to propel

vessels was made by Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, on Dalswinton

Loch, Dumfriesshire, in the year 1788. The boat used in the

experiments had a double hull, thus anticipating the twin boats

afterwards tried from time to time, one now working successfully, on

the English Channel. It measured 25 feet in length by 7 feet in

breadth, and was fitted with two paddle-wheels, one before and the

other behind the engine. It appears that Mr. Miller was endeavouring

to find some means of turning paddles fitted into small boats with

which he was experimenting, and a Mr. Jas. Taylor suggested the

steam-engine as a propelling power. This suggestion was, however,

met by the following reply from Mr. Miller: “That is a powerful

agent, I allow, but will not answer my purpose, for when I wish

chiefly to give aid it cannot be used. In such cases as the

disastrous event which happened lately, of the wreck of a whole

fleet upon a lee-shore, off the coast of Spain, every fire on board

must be extinguished, and, of course, such an engine could be of no

use.” Later on it was determined to try the steam-engine, and a

young mechanic,

Wm. Symington, was employed to superintend its

construction at Edinburgh. The result was very satisfactory, as the

vessel moved at the rate of 5 miles an hour. The boat was afterwards

laid up, and in 1789 Mr. Miller, with Taylor and Symington as

assistants, made another experiment, this time on the Forth and

Clyde Canal near Carron, at which works the engine was made. The

first trial was unsuccessful, as the paddle-wheels gave way when

full power was put on. This defect was soon remedied and a

successful trial made, the speed being nearly 7 miles an hour. The

expense and trouble in connection with this experiment caused Mr.

Miller to have the boat dismantled, although he still intended to

work out his ideas on steam propulsion.

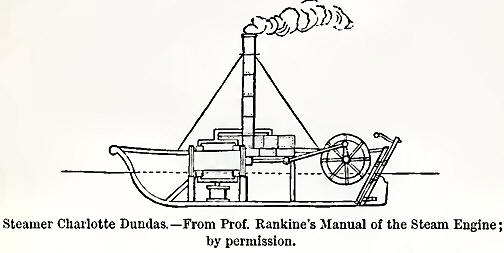

In 1801 Lord Dundas employed Symington to fit up a

steamboat for trial on the canal, and in 1802 the vessel named Charlotte

Dundas was

tried on the Forth and Clyde Canal. In this vessel Symington

introduced the important addition of a crank connection with the

paddle-wheel, whereby a direct rotatory action was kept up. The

engine was, in this way, much in advance of those previously tried,

and curiously enough remained in advance of many of the after-made

machinery for propelling the Clyde steamers, where, instead of the

action being directly applied, as in this case, the motion of the

wheels was obtained through intermediate levers and spur-wheel

gearing. In reference to this, Professor Rankine, in his Manual

of the Steam Engine,

says: “The Charlotte

Dundashad

one paddle-wheel near the stern, driven by a direct-acting

horizontal engine, with a connecting-rod and crank. The arrangement

of her mechanism was such as would be considered creditable at the

present day; and she has been justly styled by Mr. Woodcroft ‘ the

first practical steamboat.’ ”

It may be mentioned that one of the first iron

vessels was built at Faskine, on the Monkland Canal, a few miles

east of Glasgow. She was named the Vulcan, and

started with passengers from Port-Dundas to Lock 16 on the loth

September, 1819. Forty-five years afterwards she was still in good

condition, but doing service as a cargo boat.

The following verses, written by William Muir, Bird-ston,

near Kirkintilloch, in March, 1803, on seeing the Charlotte

Dunclas pass

on the canal, are interesting, as giving us a humorous glimpse into

the past, enabling those of the present day who are familiar with

such splendid achievements in marine architecture as are seen on our

ocean highways, to appreciate to some extent the difficulties which

at that time had to be overcome, and the wonder and amazement of the

beholders of the early attempts at steam propulsion:—

“When first, by labour, Forth an’ Clyde

Were taught o’er Scotia’s hills to ride,

In a canal, deep, lang, an’ wide,

Naebody thocht

That winders, without win’ or tide,

Would e’er be wrocht.

“To

gar them trow that boats would sail

Thro’ fields o’ corn or beds o’ kail,

An’ turn o’er glens their rudder’s tail,

Like weathercocks,

Was doctrine that wad needed bail

Wi’ common folks.

“They ca’d it nonsense, till at last

They saw boats travel east and wast,

Wi’ sails an’ streamers at their mast,—

Syne, without jeering,

They were convinced the blustering blast

Was worth the hearing.

“For mony a year, wi’ little clatter,

An’ naething said about the matter,

The horses haul’d them through the water,

Frae Forth tae Clyde;

Or the reverse, wi’ weary splatter,

An’ sweaty side.

“But little think we what’s in noddles,

Whar

Science sits an’ grapes and guddlcs,

Syne darklins forth frae drumly puddles,

Brings forth to view

That the weak penetration fuddles O’ me an’ you.”

The author then refers to the new lighter as being

driven

“Wi’

something that the learned ca’ steam;”

and adds:—

“By

it she through the water plashes,

An’ out the stream behiut her dashes

At sic a rate, baith frogs and fishes

Are forced to scud,

Like ducks and drakes amang the rashes,

To shun the mud.”

And after this vivid description of the rapid

movement of the novelty, he proceeds to speculate on what he has

seen:—

“Can

e’er, thought I, a flame o’ reek,

Or boiling water’s cauldron smeek,

Tho’ it war keepit for a week,

Perform sic wonders,

As quite surprises maist the folks

O’ gazin’ hunders?”

And finally finishes in a philosophic and prophetic

vein:—

“But facts, we canna well dispute them,

Altho’ we little ken about them;

When prejudice inclines to doubt them

Wi’ a’ her might

Plain demonstration deep can root them,

An’ set us right.

“Or lang gae now, wi’ whirligigs

An’ steam engines we’ll plough our rigs,

An’ gang about on easy legs

Wi’ nought to pain us,

But flit in tethers needless nags

That used to hain us.”

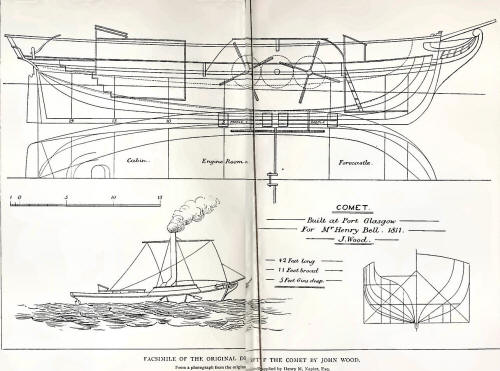

Returning, however, to the Clyde, we come upon a

notable period in our history, as in the year 1811 Henry Bell

arranged with John Wood, of Port-Glasgow, to build a vessel for him,

to be fitted with an engine by John Robertson of Glasgow. This

vessel was launched in June, 1812, with steam up, and made her first

trip to Helensburgh. She was named the Comet,

after a famous meteor which had shone across the heavens for some

time previous. This

vessel, the precursor of the long

line which followed, year by year, in growing numbers, was fitly

named. She was to many as much an apparition as the strange and

uncanny visitor of the skies, and, as with it, her train of

successors has spread, like a tail, far out in ever-widening sweep.

The Comet was

a wooden boat, 42 feet long, 11 feet broad, and 5 feet 6 inches

deep. She had the usual long funnel of the early steamers, and it

occasionally did duty as a mast, a large square sail being hoisted

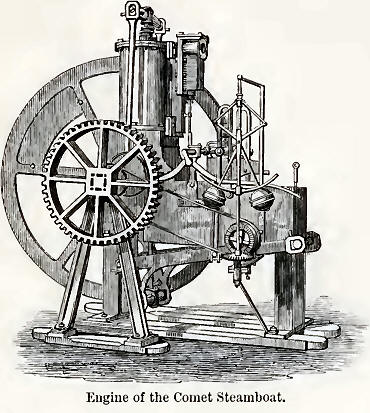

on it when the wind was favourable. The engine was made by John

Robertson, and was a condensing one of 3 horse-power, the diameter

of the cylinder being 11 inches and the stroke 16 inches. The crank

worked below the cylinder; and the engine shaft was of cast-iron,

square in section, and measured 3J inches on the side. A fly-wheel

was added to equalize the motion. The vessel was originally fitted

with two pair of paddle-wheels, 7 feet in diameter, having

spur-wheels of 31 feet diameter attached, so that, by means of

another spur-wheel of the same diameter, placed between these, and

gearing into them, each pair of paddles was rotated at the same

speed. This arrangement was obviously very inefficient, as the one

pair of paddle-wheels worked in the wash of the other pair, besides

the loss of power due to working through the toothed wheels. It is

said that Robertson, the engineer, tried to dissuade Bell from

arranging his wheels in this manner, but the latter stuck firm to

his idea, and the boat was tried with them, but proved a failure.

The double wheels were then removed, and Robertson made another

engine of about 4-horse power,having a cylinder of 121 inches

diameter. The workshop where the engine of this famous steamer was

made was situated in Dempster Street, a small street off North

Frederick Street, in the north part of Glasgow. The original model

of the Comet is

in the possession of Messrs. John Reid & Co., shipbuilders,

Port-Glasgow, and shows the double set of paddle-wheels as

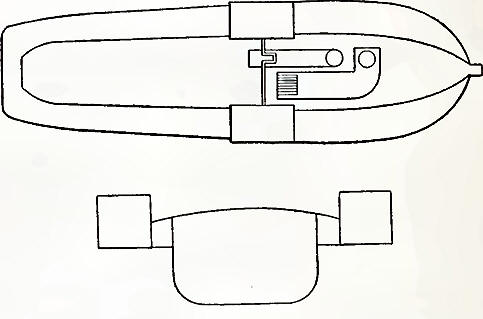

originally proposed and tried. See plate, which is a facsimile from

a photograph of the original draft of this vessel, kindly supplied

by Henry M. Napier, Esq. The drawing shows the vessel in both plan

and section, with the first-tried arrangement of the double

paddle-wheel on each side, also the spur-wheel gearing connecting

the engine with the paddles.

The navigation of the river had up till this time

been managed by boats, which, with the combined exertions of sail

and oars, made the passage up and down the river at more or less

regular intervals, as the time of the passage depended much upon

wind and tide. Thus Pennant, visiting the Clyde in 1772, tells us

that after passing Dumbarton, on his way to Greenock, they had “a

long contest with a violent adverse wind and very turbulent water.”

Bell appears early to have turned his attention to

the use of the paddle with hand power, some attempts having been

also made in this direction by a Mr. Bennie of Greenock. As in later

trials of this method of propulsion, the labour was found greater

than that required with the oar. It might, however, be supposed

that, by the use of ball-bearings, which have so much conduced to

the success of the modern velocipede, the resistance due to the

friction of the shaft of a paddle-wheel open pleasure-boat might be

greatly reduced. It is said that Brunei fitted a collar to the

rudder-post of the Great

Eastern, which,

resting on cannon balls, became really an early form of

ball-bearing.

The boiler of the Comet was

made by David Napier, a name to be afterwards widely associated with

the progress of steam shipping on the Clyde. The following is a copy

of Bell’s advertisement of his new boat: “The Steamboat Comet, between

Glasgow, Greenock, and Helensburgh, for passengers only.—The

Subscriber, having at much expense fitted up a handsome vessel to

ply upon the river Clyde from Glasgow, to sail by the power of air,

wind, and steam. He intends that the vessel shall leave the

Broomielaw on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, about mid-day, or

such an hour thereafter as may answer from the state of the tide;

and to leave Greenock on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, in the

morning, to suit the tide. The elegance, comfort, safety, and speed

of this vessel require only to be seen to meet the approbation of

the public; and the proprietor is determined to do everything in his

power to merit general support. The terms are for the present fixed

at 4s. for the best cabin and 3s. for the second, but beyond these

rates nothing is to be allowed to servants or any person employed

about the vessel.

“The subscriber continues his establishment at

Helensburgh Baths, the same as for years passed, and a vessel will

be in readiness to convey passengers by the Comet from

Greenock to Helensburgh.

“Helensburgh Baths, 5th August, 1812.”

This advertisement of Bell’s in which the power of

wind is referred to, brings up forcibly the condition of the early

navigation of the Clyde when the passenger communication with

Greenock and the other lower ports of the river was carried on by

means of what were termed Fly-Boats, which

made their passage to and fro by means of the power of wincl and

oars, occasionally, it is said, being helped by horse power. The

incidents in such journeys must have been frequently of a humorous

description, as the following graphic sketch which appeared some

years ago in the Glasgow

Herald will

show: “The passage to Greenock in favourable circumstances was

accomplished in about ten or twelve hours; as much depended on the

flow of the tidal wave, not unfrequently the passage was interrupted

for a night at Bowling. It was surmised that the flies were

intercepted there by a net or web in the shape of a tavern. The

passengers had frequently to remain in their ark, or get quarters in

the ‘public’ until the morning. A story was told and vouched that

when a ‘fly ’ had been thus arrested for the night, and the crew

were called in early and dusky morn to avail themselves of the

favourable tide, the two boatmen, who had been meantime indulging in

strong drink, set to work with their oars. With the dawn the

passengers had a dreamy notion that they were making little or no

progress as the outline of the castellated rock, still phantom-like,

appeared in the mist. Calling the attention of the rowers to their

apprehensions, the fact was painfully realized by the following

colloquy between the ancient mariners: ‘Tonalt, did you lift t’

anchor?’ and the discouraging reply,‘Na,Tougal, not me, but ’twas

your duty.’” From the Memorials

of James Watt we

learn that these Flyboats were built by W. Nicol, a Greenock

boatbuilder, and that they were a great improvement on the smaller

packet boats. They measured about 28 ft. in length by 8 ft. beam,

and were wherry-rigged. The passengers were protected from the

weather by a cover over the after part of the boat. A projecting

platform ran round the deck outside of this cabin for the crew to

pass and repass, and on fine weather by favour of the commanding

officer some of the passengers were allowed to sit upon the roof

with their feet on the passage way. The boats generally left

Greenock with the flood-tide, and if the wind was also favourable

Glasgow might be arrived at in from four to five hours. As late as

1820-1830 fly-boats without sails were used; these were simply large

stout open boats, which were rowed by four men. They plied to

Greenock from the foot of a long flight of stairs at the Broomielaw.

About that time the passage to Greenock by the steamers took

sometimes three hours, and the cost was 5s. in the cabin and 2s.

6c?. in the steerage. A wherry sailed from Greenock to Helensburgh

and the Gareloeh in opposition to

the steamers.

To facilitate this traffic there was a towing-path

down as far as Renfrew, and it is interesting to read in Cleland’s Annals

of Glasgow under

“Abstract of Regulations for Steam Boats and other Vessels.”—“That

none of the said Steamboats shall cross the tracking or towing lines

of the vessels plying on the river where there is room to pass on

the off side, under the penalty of £5 for

each offence.” And further “ That none of the said Steamboats shall

ply in the twilight or in the dark without having lights ahead

fitted up properly.” This regulation does not intimate the colour of

the lights, or if they were to be fitted to the paddle-boxes; and it

was no doubt at a later date that the well-known red and green

paddle-box lights were introduced, which, on first sight, frightened

some of the boatmen who happened to be out on the river during a

heavy spate, one of them declaring that an apothecaries’ shop had

been carried away and was drifting down on them.1

Even after the introduction of the steamboats the

shallow condition of the Clyde at low water, together with the

numerous sandbanks, made the navigation difficult and somewhat

uncertain, as the boats frequently got aground and had to lie till

the tide rose, the passengers sometimes assisting in getting a start

by running from side to side to loosen the keel out of the sand.

Besides the use of coloured lights for the more complete guidance of

vessels meeting or crossing each other’s path, the position and

method of fixing the lamps are now specified. Thus a steamship shall

carry on the front of the foremast at a height of not less than

twenty feet a bright white light, on the starboard side a green

light, and on the port side a red light. A sailing vessel shall

carry the red and green side-lights only. The rules for the

mariner’s guidance have been humorously put into rhyme by Thomas

Gray, C.B., secretary to the Board of Trade, thus:

TWO STEAMSHIPS MEETING.

“When all three lights I see ahead,

I port my helm and show my Hed.

TWO STEAMSHIPS PASSING.

Green to Green, or Tted to Ped—

Perfect safety—go ahead !

Very safe and good advice is given in the last

stanza:

“Both in safety and in doubt,

I always keep a good look-out;

In danger, with no room to turn,

I ease her! Stop her ! Go astern!”

The connection with places further down the river was

accomplished by the steamboats carrying the passengers to Greenock,

who then went by sailing packets to their destination. It is

recorded by a traveller in 1815 that he sailed in the Comet from

Glasgow for Greenock, leaving in the morning and arriving at

Greenock after a seven hours’ passage, three hours of which had,

however, been spent lying on a sand-bank at Erskine. At Greenock he

went on board the Rosa packet

and landed in Rothesay the same day, much to the surprise of the

residen-tcrs there, as the passage was an extraordinarily fast one.

The Comet was

followed by the Elizabeth, of

33 tons, built in 1812-13, by John Wood. She measured 58 ft. long

over all, 51 ft. keel, 12 ft. beam, and was 5 ft. deep. The engine

was made by James Cook of Trades-ton, Glasgow, and was of 10 h.p. The

following copy of an advertisement in reference to this steamer is

given in a work on Steam

and Steam Navigation, by

J. Scott Russell, and is interesting as giving us a good deal of

insight into the appearance and management of the early Clyde

steamers: “The Elizabeth was

started for passengers on the 9th of March, 1813, and has continued

to run from Glasgow to Greenock daily, leaving Glasgow in the

morning and returning the same evening. The passage, which is

twenty-seven miles, has been made, with a hundred passengers on

board, in something less than four hours, and in favourable

circumstances in two hours and three-quarters. The Elizabeth has

sailed eighty-one miles in one day, at an average of nine

miles an houv. The

Elizabeth measures

aloft tifty-eight feet; the best cabin is twenty-one feet long,

eleven feet three at mid-ships, and nine feet four inches aft,

seated all round, and covered with handsome carpeting; a sofa,

clothed with maronc, is placed at one end of the cabin, and gives

the whole a warm and cheerful appearance. There are twelve small

windows, each finished with marone curtains, with tassels, fringes,

and velvet cornices, ornamented with gilt ornaments, having

altogether a very rich effect. Above the sofa there is a large

mirror suspended, and at each side book-shelves are placed,

containing a collection of the best authors, for the amusement and

edification of those who may avail themselves of them during the

passage—other amusements are likewise to be had on board. The engine

stands amidships, and requires a considerable space in length, and

all the breadth of the vessel. The forecastle, which is rather

small, is about eleven feet six by nine feet six inches, not quite

so comfortable as the after one, but well calculated for a cold day,

and by no means disagreeable on a warm one; all the windows in both

the cabins are made in such a way as to shift up and down like those

of a coach, admitting a very free circulation of fresh air. From the

height of the roofs of both cabins, which are about seven feet four

inches, they will be extremely pleasant and healthful in the summer

months for those who may favour the boat in parties of pleasure.

Already the public advantages of this mode of conveyance have been

generally acknowledged; indeed, it may without exaggeration be said

that the intercourse through the medium of the steamboats between

Glasgow and Greenock has, comparatively speaking, brought these

places ten or twelve miles nearer to each other. In most cases the

passages are made in the same time as by the coaches; and they have

been, in numerous instances, done with greater rapidity. In

comparing the comfortableness of these conveyances, the preference

will be given decidedly to the steamboat. Besides all this, a great

saving in point of expense is produced; the fare in the best cabin

being only four shillings, and in the inferior one two shillings and

sixpence; whereas the inside of a coach costs not less than twelve

shillings, and the outside eight shillings.”

The Clyde, 69

tons, was also built by John Wood. She was 76 ft. long over all, 72

ft. keel, by 14 ft. beam, and depth of hold of 7½ ft. The engine was

made by John Robertson; the cylinder was 22 in. diameter, with a

2-foot stroke, and of 14 H.P. The

speed attained was six miles per hour.

The Glasgow, 74

tons, was built by John Wood, and was 72 ft. long by 15 ft. beam.

The engine was a side-lever one, of 16 h.p., with

a cylinder 20 in.

diameter, stroke 2 ft., and was made by James Cook. This vessel ran

to Largs and Millport, and must have been the first boat on this

station. She could run from Glasgow to Greenock with the tide in two

hours and ten minutes. The form of these early boats is shown by the

annexed plan and section.

In 1814, six steamers appear to have been built—viz.

the Industry,

Trusty, Princess Charlotte, Prince of Orange, Marjery, and Argyle. The Industry, still

existing, was built, it is said, by Fyfe at Fairlie in 1814, her

builders being afterwards celebrated for their racing yachts; a

reputation which the firm, still flourishing, maintains. Her

dimensions are as follows: Length, 68 ft.; breadth, 17 ft.; depth, 8

ft.; gross tonnage, 69; register, 42; one cylinder, 16 in. in

diameter. She had at first a copper boiler, not an uncommon

arrangement in those early days, of low pressure; but it was

afterwards replaced by an iron one. The original engine was also

replaced about 1826 by the one now on board. One special feature of

interest, which can still be inspected, is the spur-wheel gearing to

connect the engine with the paddle-shaft. From

the grinding sound caused by the spur-wheels she was known at

Greenock as the “ Coffee-mill.” The original engine was by Thomson,

of Tradeston, and the second engine by Caird, of Greenock. The

paddle-wheels are 11 ft. diameter, with floats 2 ft. 9 in. long, ten

on each wheel; stroke of engine, 2 ft.; diameter of shaft, 51 in.;

spur-wheels, 2 ft. and 1-1 ft. in diameter. TheIndustry was

the seventh steamer

on the Clyde, and must now be the oldest steamer in existence. She

plied between Glasgow and Greenock, principally as a luggage boat,

but occasionally ventured down the firth as far as Campbeltown.

Strangely enough, at the present time the Clyde

contains two of the greatest curiosities in marine architecture,

viz. the oldest steamer extant—the Industry—

and the largest vessel in the world—theGreed

Eastern, which

for some time has been lying at the “Tail of the Bank,” oft'

Greenock. The dimensions of the latter, as given in the

advertisement of bill of sale, is: Length, 670'6 ft.; breadth, 82-8

ft.; depth, 60 ft. Tons B.M., 22,927; tons gross, 18,915; tons nett

register, 13,34k Screw engines, 1,600 h.p. nominal;

paddle engines, 1,000 H.P. nominal.

On comparing these dimensions with those of the Industry, we

find that the Great

Eastern is

ten times longer, about five times broader, and seven and a half

times deeper. The tonnage is about three hundred times greater.

It may be interesting to note that the combined

length of these seven precursors of steam traffic on the Clyde was

little over 400 ft., so that, if placed end to end, they could all

have been carried by such a vessel as the Anchor Line steamer Furnessia, now

sailing from the Clyde, which measures 445 ft. long.

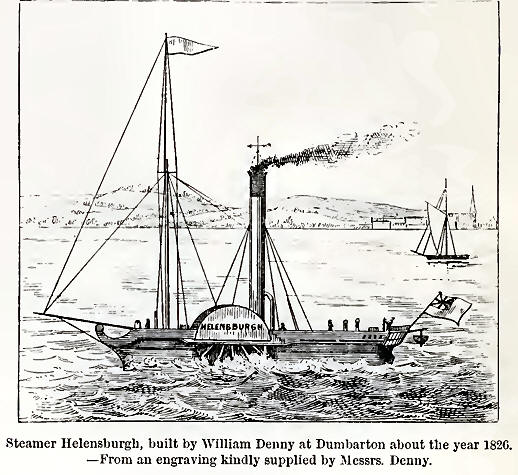

The Trusty was

a boat like the Industry, and

is said to have been the first steamer built at Dumbarton; the

builder being Wm. Denny. She was 68 ft. long, with a breadth of 17

ft. 6 in., having a geared side-lever engine of 10 h.p. made

by George Dobbie, Tradeston. Like the Industry, she

got a new engine of greater power at a later date. This boat appears

to have sunk in the river after a collision, but was afterwards

raised and converted into a schooner, and wrecked in 1854 off* Loch

Ryan.

The Princess

Charlotte and Prince

of Orange were

built by Mr. Munn of Greenock, and engined by Boulton & Watt.

The Marjery was

built at Dumbarton by William Denny, and engined by James Cook, with

a single side-lever engine of 10 h.p. Her

dimensions were 63 ft. long by 12 ft. beam. This vessel was sent to

the Thames about 1815. When the Marjery sailed

past the Nore, at which part of the British fleet was lying, she was

closely scrutinized by the old salts on board; one of them, who

belonged to Dumbarton, gave her a cheer, adding, “Well done,

Dumbarton! ”

The Argyle, 78

tons, was built at Port-Glasgow, and engined by James Cook, with a

single side-lever engine of 14 h.p. She

was a similar vessel to the Albion, and

appears to have gone to the Thames in 1815.

In 1815 other six steamers appear to have been added,

viz. the Waterloo,

Argyle No.

2, Greenock,

Caledonia, Dumbarton Castle, and Britannia.

The Waterloo, 90

tons, was built and launched after the celebrated battle was fought,

and was similar to the Argyle. She

plied on the Helensburgh station. The engines were by James Cook,

and were of 20 h.p.

Among the songs which appeared from time to time in

reference to the early boats, one refers to the Waterloo as

follows:

“And now amid the reign of peace

Arts guiding stream we ply,

That makes our wheels, like whirling reels,

O’er yielding water fly.

As our heroes drove their foes that strove

Against the bonnets blue,

On every side the waves divide

Before the Waterloo.”

The Greenock, G2

tons 10 h.p., appears

to have been built by Archibald M'Lauchlan at Dumbarton. The Caledonia, 102

tons, was built by Messrs. Wood, Port-Glasgow. She measured 95 ft. 6

in. long by 15 ft. beam; draft 4h ft.

to 5 ft., and had two engines of 16 h.p. each,

made by the Greenhead Foundry Co. This vessel went in 1816 to the

Thames, and was afterwards placed on the

Rhine. The Dumbarton

Castle, 81

tons 32 h.p. (two

of 16 H.P. each),

built by Archibald M'Laucldan, Dumbarton, and engined by Duncan

MArthur & Co., Camlachie, was the first steamer to make a trip to

Rothesay, and the event was marked by the presentation of a handsome

punchbowl to the captain, James Johnston. This vessel appears to

have been wrecked in the Clyde in 1829. The

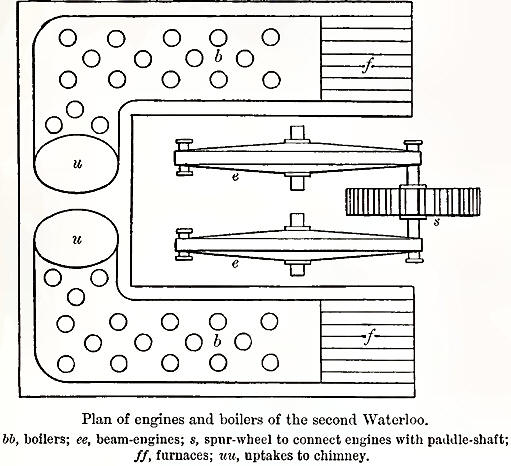

Britannia, 109

tons, 32 h.p., with

a draft of 4 ft. G in., measured about 80 ft. long by 16 ft. beam.

Her engines were made by James Cook, and consisted of a pair of

beam-engines and spur-wheels to raise the power to the paddle-shaft,

similar to those of the second Waterloo (see

cut p. 183). The cylinders were 20 in. diameter, with 2 ft. 6 in.

stroke. This vessel plied to Campbeltown and made a trip to

Londonderry, thereby opening up the trade with the latter port. She

appears to have been wrecked off Donaghadee in 1829.

The following is a copy of an advertisement appearing

in the Glasgow

Herald of

June, 1815:—“The proprietors of the Britannia steamboat

beg leave to inform the public that she, according to advertisement,

performed her voyage to Largs, Rothesay, and Campbeltown, and

returned in such a short time, and gave so great satisfaction, that,

owing to an agreement with the public of Campbeltown, they will be

under the necessity of abandoning the voyage to Inveraray, as

advertised for tomorrow, but will upon Monday first, at ten o’clock,

sail for Greenock, Gourock, Rothesay, and Campbeltown, and return on

Wednesday. As the voyage is far, the passengers will be accommodated

with refreshments, suitable and agreeable for them.”

The Britannia appears

to have had a beam-engine. The Industry engine

is of the side-lever type; very much like a beam-engine inverted.

Beam-engines are still used in America to a large extent; one of the

largest examples of these being the engine of the Pilgrim, built

in 1882, and now plying on the Fall River route by Long Island

Sound, between New York and Boston. These engines have not found

favour on the Clyde, but occasionally boats fitted with them for the

China river service may be seen at the works of Messrs. A. & J.

Inglis. About the last large mail paddle-steamer to be fitted with

the side-lever engine was the Persia, of

the Cunard Co., engined by Messrs. R. Napier, Glasgow. Another

existing example of the side lever can still be seen at Dumbarton,

and from its position can be readily inspected. There, the engine of

the Leven, the

first marine engine made by Robert Napier in 1824, has been erected

on a pedestal at the foot of the great rock which has for so long

silently looked down on the productions of the toiling hands and

inventive brains of the workers of the Clyde.

In 1816 we have further additions, viz. the Neptune,

Albion, Rothesay Castle, Lord Nelson, Lady of the Lake, and Duke

of Wellington. This

latter vessel appears to have been built by William Denny in 1817,

but was a few years afterwards lengthened and named the Highland

Chieftain, running

to the Highlands till about 1838. Of these the Albion, 92

tons, was built by J. Wood, and measured about 70 ft. by 13 ft.

beam, with draft of 4 ft. The engine (side-lever) of 20 h.p. was

by James Cook, the cylinder being 22 in. diameter, with a 2-ft.

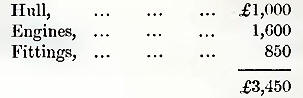

stroke. She plied to Largs. The cost of this vessel is stated as—

The Lady

of the Lake, engined

by James Cook with a single side-lever engine, appears to have been

transferred to the Firth of Forth, and after plying there was sent

to the Elbe, but was afterwards brought back. In 1817 only two boats

appear to have been added, viz. the Marion and

the Defiance. Of

these the Marion appears

to have been the first steamer on Loch Lomond, where she plied in

1820 in connection with the Post

Boy steamer

from Glasgow. The year 1818 brought several additions, viz. the Rob

Roy, Marquis of Bute, Woodford, Active, and Despatch. The Rob

Roy is

the most interesting, as she was the first steamer to ply to

Belfast. She was 90 tons and of 30 h.p., with

a draft of 7 ft., and was built by William Denny, at Dumbarton,

engined with a single side-lever engine by David Napier, and was

latterly transferred to the Dover and Calais service. Previous to

starting this steamer it is said that Mr. Napier crossed to Belfast

during a storm in a sailing vessel, and watching the effect of the

waves was convinced steam could be utilized to overcome them. He

then by means of experiments on model boats determined to give his

proposed steamer a sharper entrance at the bow than was at that time

common for the river steamers.

In 1819 the second Waterloo was

built by Scott of Greenock, and was the longest steamer afloat at

that time, measuring about 120 feet long by 22 feet beam. She had

two beam-engines with 30-inch cylinders and 3 feet stroke,with

spur-wheels to connect with the paddle-shaft. See annexed cut.

In 1819 Mr. David Napier had the Talbot built

for him by Messrs. Wood. She was 150 tons, and had two of Mr.

Napier’s engines of 30 h.p. each.

The Talbot plied

between Holyhead and Dublin, and appears to have been a very

complete and efficient vessel. Another vessel, the Ivanhoe, was

added to this route. She was 170 tons burthen, built by Scott of

Greenock, and engined by Mr. D. Napier with engines of 60 h.p. In

the same year

Mr. D. Napier established the first line of steamers

between Glasgow and Liverpool, the Robert

Bruce of

150 tons and 60 h.p. being

the first to start. She was built by Messrs. Wood and engined by Mr.

D. Napier.

Two others were added, viz. the Superb, in

1820, of 240 tons and 70 h.p., and

the Eclipse, in

1821, of 240 tons and 60 h.p. The

former was built by Scott, and the latter by Steele of Greenock, the

engines in both cases being by Mr. D. Napier.

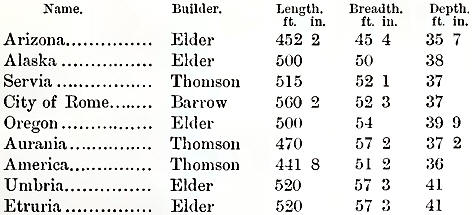

We may now look at one or two pictures of the early

boats, and their successors of the present day. Compare the Superb of

1820, and the Etruria, one

of the largest and most powerful vessels now 011 the

Atlantic service. The Steamboat Companion for 1820 tells us that

“The Superb, is

at this moment the finest, largest, and most powerful steam vessel

in Britain. She registers 241 tons, and is impelled l>y two very

fine engines of 36 H.

P. each,

to which copper boilers are attached. The average duration of the

passage from the Clyde to Liverpool does not exceed thirty hours;

fare, £2, 15s.” Contrast this with what the Times for

1885 says:

“The Etruria is

a sister ship to the Umbria, both

built by John Elder & Co., of Fairfield, Govan, the largest, most

finished, and fastest vessels in the Atlantic service. She is built

entirely of steel, and is divided into ten water-tight compartments.

She is 520 ft. long by 57 ft. 3 in. broad, and 41 ft. deep. The

coming season will be an interesting one to the Atlantic traveller

and to those who watch the performance of the vessels. The list is

filled up for the present. There is nothing on the stocks and

nothing projected to compete with what is on the water, and the

public interest will centre in nine vessels, constructed within the

last eight years, as follows:—

“The Etruria is

fitted to accommodate 720 first-class passengers. Several of the

state-rooms are fitted en

suite for

family use, and every advantage has been taken of the breadth of the

vessel to afford variety and greater space in the accommodation. The

saloon will seat 280 people at dinner, and as the electric lamps are

fixed high up near the ceiling by slender pendants the view is

unobstructed throughout the chamber. The panelling of the saloon is

all in light wainscot oak, with a dark walnut sideboard at the

service end and a bookcase at the other. Above, in the form of a

sort of gallery, is a music-room; and on the same upper deck are a

number of superior state-rooms in the middle of the ship. Above

these, and running for 300 feet in length throughout the entire

breadth of the ship, is a promenade deck. Here is the captain’s room

and a large saloon, exclusively set apart for ladies, sumptuously

upholstered in green velvet and panelled in maple. Below, on the

main deck, on a level with the saloon, is a boudoir, which forms a

vestibule to the baths and lavatories set apart exclusively for

ladies. Altogether there are 13 marble baths, fitted with steam and

shower apparatus; and lavatory accommodation is dispersed throughout

the ship. On the main lower decks are placed the major portion of

the state-rooms. Each of them is provided with a hot-water heating

apparatus, an electric light, and a life-saving cork jacket for each

berth. The smoking-room, which is unusually large, is fitted with

red leather benches/and is panelled in maple and oak. It is placed

on the upper deck. The electric light is produced by four of

Siemens’s machines, each with its own three-cylinder engine. Three

of them are sufB-cient to maintain the whole 850 lamps of the ship,

so that one is always in reserve, and oil lamps are entirely

dispensed with. The passages, the engine-room, and boiler-house are

lighted day and night, and some of the lights of the saloon are also

maintained during the night. The engines are marvels of

construction, and are unequalled, except by those of the Umbria, for

strength, power, and simplicity. With good coals they are capable of

indicating upwards of 14,000 horse-power, with nine boilers, but the

speed attained by the Etruria has

been secured by some thousand horse-power less than the maximum. The

boilers are fired by 72 of Fox’s corrugated furnaces. They work at a

pressure of 100 lbs., which was maintained during the cruise with a

total absence of smoke, even with inferior coals.”

In speaking of the progress of steam navigation, Dr.

Cleland says, “ The success of steamboats on the Clyde induced some

gentlemen in Dublin, to order two vessels to be made to ply as

packets in the channel between Dublin and Holyhead, with a view of

ultimately carrying the mails. They were built by Mr. James Munn,

Greenock, have engines of twenty horse-power, made by Mr. James

Cook, Tradestown, Glasgow, and are named Britannia and Hibernia. Mr

Cook, whose eminent abilities as an engineer, have enabled him to

make numerous improvements on machinery, has been very successful in

constructing the paddles of these packets, so that one man can

easily raise them from five to six feet out of the water, while the

engine is at work, in the event of a heavy gale making that measure

necessary.” The author is indebted to Mr. Robert Cook, a nephew of

the Mr. Cook referred to, for much personal information of the

sizes, powers, and general appearance of these early steamers.

We have clearly in the Superb reached

a point, eight years later only than the launching of the Comet, when

steam navigation on our coast may be considered completely and

efficiently established. Certainly the time stated as taken on the

voyage to Liverpool is long, but it took some years and many

improvements in both vessels and machinery to reduce it to 18 hours

from Greenock by the

Unicorn in

1837, and in 1841 to 16½ hours by the Princess

Royal. The

Liverpool steamers about 1837, the Unicorn and Actceon, appear

to have been very handsomely furnished, and even carried a chaplain

with them who conducted divine service on Sunday. The chaplain had a

special room to himself with a brass plate marked “Chaplain’s Room.”

Notwithstanding all these advantages it was still considered a

serious event to make the Liverpool journey, some travellers making

their “will” and taking a special farewell of their friends ere they

started. |