|

The Clyde rises from the northern border of the great

Silurian rocks of the Southern Highlands, flowing along these until

about Symington, where it enters the Old Red and afterwards the

Carboniferous basin onwards to Glasgow. The Silurian system of the

south of Scotland is described as follows by Professor Young: “The

broad undulating district lying to the south of the Carboniferous

basin of Central Scotland, and known under the general name of

the Southern Uplands, is carved almost wholly out of rocks of

Silurian age. The dominant formation is an immense series of

comparatively barren graywackes and shales, which, thrown into

innumerable folds and contortions, spread in an unbroken

sheet from St. Abb’s Head to the Mull of Galloway,

forming by far the grandest exhibition of Middle Silurian Strata yet

discovered.” Page, in his Text Booh of Geology, says: “This system

is largely developed in various countries, both in the Old and in

the New World, and typically so in the district between England and

Wales, anciently inhabited by the Silures; hence the designation

‘Silurian System’ by Sir It. Murchison, their first and most ardent

investigator.”

The Clyde valley presents varied geological features,

and offers a very good field for the study of this now important

economical science. The rocks throughout are of the earlier and

Carboniferous periods, seamed by dykes and capped by overflows of

trappean rocks, indicating great changes of level and conditions in

the past; whilst to the student of the glacial period abundant

evidences of the presence of a great ice-sheet once more or less

filling up the valleys, as the glaciers of Switzerland and Norway

now do, may be met with in the boulders scattered about the lower

levels, the great masses of boulder-clay, and the smoothed and

striated rock surfaces which may still be met with. In reference to

this it may be noted here that “A table-case in the Hunterian Museum

contains a series of hand specimens, obtained by Mr. Young from the

boulders which were removed when the summit of Gilmorehill was

lowered for the foundation of the University. The series includes

all varieties of rock from Bonawe to the Kilpatricks. The glacial

striations of the district are generally from north-west to

south-east.”

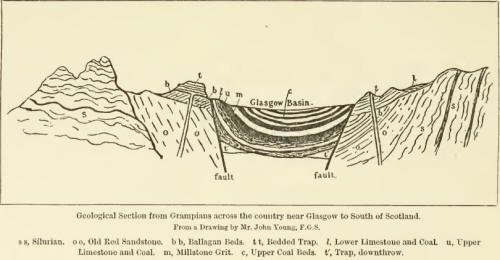

If we take a sectional view of the country, in a line

running north and south through the Clyde valley and passing through

the Glasgow district, we find the Silurian rocks appearing to north

and south, as a framework on which rests deposits of Old Red

Sandstone, on which, in turn, rest the limestone, shales, and coal

and iron beds of the Carboniferous period. Ejections of trappean

rocks are frequently met with in the later deposits, troubling the

miner by causing upthrows and downthrows.

The most widely-spread and most interesting series,

in an industrial point of view, is the Carboniferous, covering-all

the middle portion of the Clyde valley, and extending to a depth of

several thousand feet. The series consists mainly of beds of coal,

iron-stone, shales, and fire-clay, with their accompanying

limestones and sandstones.

The great “fault” already referred to as crossed by

the Rotten Calder has caused the downthrow of the great coal-beds to

a level with the lower deposits of the carboniferous limestone,

shown in a geological map of the district by a sharp dividing line

between the dark-coloured portion (the coal) and the bluish (the

limestone). The amount of this displacement equals that of the

thickness of the beds awanting, and has been estimated at about 1500

feet. Speaking of the limestones to the south of Glasgow Mr. Bell

(Rocks around Glasgow) says:—

“They are also often called the ‘cement limestones,’

being largely used for cement and building purposes, as from a

certain admixture of silica and alumina in their composition they

have the property of ‘setting’ with a firm band under water. The

Orchard limestone is wrought at a short distance to the south of

Giffnock Quarries. It is also wrought as the ‘Lyoncross’ limestone

at Nitshill and Barrhead, and is known as the ‘Williamwood’

limestone near Cathcart. It is only a thin bed, from 18 to 26 inches

in thickness, but is of excellent quality, and has long been

esteemed as a cement limestone. Underneath it is a thin seam of

coal, which is used in calcining the stone. The Arden limestone,

wrought extensively near Thornliebank and Barrhead, is in much

greater mass, attaining a thickness of 8 to 10 feet, in some places

even more. Its equivalent to the north of the Clyde, in the Garnkirk

district, is largely used for iron-smelting.”

The varieties of coal, and varying condition and

thickness of the limestone and sandstone beds, all point to long

periods of land surface, with correspondingly extended periods of

depression under the surface of the water.

Professor Geikie, in his Scenery of Scotland, thus

graphically describes the Clyde valley:—

“While the three main rivers resemble each other in

thus breaking through a chain of hills to find their way into their

firths, they present many points of difference in their respective

courses across the lowland valley. Perhaps the most interesting is

the Glyde. Drawing its waters from the very centre of the southern

uplands, it flows transverse to the strike of the Silurian strata,

until entering upon the rocks of the lowlands at Roberton it turns

to the north-east, along a broad valley that skirts the base of

Tinto. If the reader will glance at the map he will notice that at

that part of its course the Clyde ap-proaclies within seven miles of

the Tweed. Between the two streams, of course, lies the watershed of

the country, the drainage flowing om the one side into the Atlantic,

and on the other into the North Sea. Yet, instead of a ridge or hill

the space between the rivers is the broad flat valley of Biggar, so

little above the level of the Clyde that it would not cost much to

send that river across into the Tweed. Indeed, some trouble is

necessary to keep the former stream from eating through the loose

sandy deposits that line the valley, and finding its way over into

Tweeddale. That it once took that course, thus entering the sea at

Berwick instead of at Dumbarton, is probable; and if some of the

gravel mounds at Thankerton could be re-united it would do so again.

Allusion has already been made to this singular part of the

water-shed. Its origin is probably traceable to the recession of two

valleys, and to the subsequent widening of the breach by atmospheric

waste and the sea.

“From the western margin of the Biggar flat the Clyde

turns to the north-west, flowing across a series of igneous rocks

belonging to the Old Red Sandstone series. Its valley is there wide,

and the ground rises gently on either side into low undulating

hills. But after bending back upon itself, and receiving the Douglas

Water, its banks begin to rise more steeply, until the river leaps

over the linn at Bonnington into the long, narrow, and deep gorge in

which the well-known falls are contained. That this defile has not

been rent open by the concussion of an earthquake, but is really the

work of sub-aerial denudation, may be ascertained by tracing the

unbroken beds of lower Old Red Sandstone from side to side. Indeed,

one could not choose a better place in which to study the process of

waste, for he can examine the effects of rains, springs, and frosts

in loosening the sandstone by means of the hundreds of joints that

traverse the face of the long cliffs, and he can likewise follow in

all their detail the results of the constant wear and tear of the

brown river that keeps ever tumbling and foaming down the ravine.” |