|

On Board the Clanranald - A

Great Gaelic Poet - The Green Isle of St. Finnan - The Coffin on the Floor

- I Reach Glenfinnan - Gregory's Mixture - The Truth about the Notorious

Jenny Cameron-The Chapel on the Hillside.

IT was chilly on the deck

of the little loch steamer next morning. The day was grey with drizzling

rain, and I stood beside the wheel talking to the Captain as the boat took

us north-east to Glenfinnan. I was sorry to leave Acharacle, where

Gillespie and Grant were remaining for another twenty-four hours before

making tracks for home, and would fain have lingered for a few more days

listening to Campbell's stories of old Moidart; but the untravelled miles

of the journey ahead of me had made me restless.

The steamer touched at the

little wooden pier at Dalilea, and we took on board some chickens in

wicker coops. Among the trees I saw the grey-walled house, with its funny

little mock-baronial turrets, which I had found packed with a boat-load of

tourists when I had sought shelter three nights before.

It was at Dalilea that the

Prince arrived on foot on the 18th of August, 1745, on his way to

Glenfinnan, and he had been rowed half-way up Loch Shiel to sleep the

night under the roof of Macdonald of Glenaladale. It was at Dalilea, too,

that Alexander Macdonald the Gaelic poet was brought up. His father, the

Rev. Alexander, was the Episcopal minister of the church at Kilchoan in

Ardnamurchan, nearly thirty miles away, but he preferred to live on his

farm at Dalilea, and do the sixty-mile tramp on foot every Sunday.

According to Father Charles Macdonald, the Episcopal minister had a

difficult time of it at Dalilea, hemmed in as he was by neighbours who

were solidly Catholic. They deliberately allowed their herds to stray over

his land, and often he was forced to lay a stick across the backs of their

owners. But the Rev. Alexander, whose physical strength was prodigious,

was not a man to be trifled with. Once he sold a cow to a neighbour who

nimbly avoided paying for the beast. Meeting his debtor one day by the

lochside, the minister's anger got the better of him, and he seized the

man and shoved him into a hole below some crags. He was in the act of

blocking up the entrance with a huge slab of stone when Macdonald of

Glenaladale came along. The minister faced the Laird and told him why one

of his crofters was being treated in a way which at first glance might

seem a trifle hard.

"An effective punishment,"

nodded Glenaladale; "but aren't you making the payment for your cow

further off than ever?"

"Not at all," declared the

minister. "I'll let the scoundrel out as soon as one of his friends stands

surety for the money that's due to me."

Smiling, the Laird took the

hint; he promised to see that the debt would be paid at once; and the

minister put his huge shoulder to the slab of stone, allowing the offender

to crawl from his temporary tomb.

The young poet, his second

son, was sent to Glasgow University to study law, but he fell in love with

Jane Macdonald of Dalness and married her - Little Jean with the Yellow

Shoes she was called. This marriage cut short his legal studies, and he

returned to the Highlands,' and eventually became schoolmaster and

catechist at Kilchoan. On the Loch Sunart shore his industry must have

been terrific, for besides teaching in the school he worked a croft to add

to his few pounds of salary, and in the evenings he compiled the first

Gaelic-English dictionary that was printed in Scotland. He had

abandoned the school before the 'Forty-five, and was probably living at

Dalilea when-according to the Moidart Muster Roll-he joined the Prince

armed with gun and pistol. By this time he was a middle-aged man, though

bad fortune had not damped his boyish impetuosity, and he was one of the

most fervent Jacobites in Scotland.

Many guesses have been made

at the identity of the "Lockhart Chronicler," who might be called the

mystery-man of the 'Forty-five. He left a narrative of his experiences,

telling among other things how he became the Prince's Gaelic teacher, and

how he was sent to recruit in Ardnamurchan, "and soon returned with 50

cliver fellows who pleased the Prince." This anonymous chronicler is now

believed to have been Alexander Macdonald. And indeed who could have been

more able to instruct the Prince in Gaelic than the author of the first

Gaelic dictionary-and who could have recruited with more success in

Ardnamurchan than the man who for some years had been a schoolmaster there

and knew the people well ? They say in Moidart that he knelt behind the

Prince at Glenfinnan; Charles used the poet's knee as a seat; and

Macdonald there and then composed a song in his honour.

A few years after the

Rising, he settled down on a small farm in Moidart. But soon they cleared

him out of the district. He had published a volume of Gaelic poems,

entitled "The Resurrection of the Old Scottish Tongue," which poured

vitriol on King George's head, and the public hangman in Edinburgh was

ordered to burn the book. But the story goes that there was a double

reason for the poet's expulsion. The parish priest, to his dismay, found

that Alexander Macdonald had a taste for writing lewd verses, and had been

reciting them to his neighbours. Fierce in his enthusiasms, Macdonald was

first of all an Episcopalian, then a Presbyterian, and lastly a Catholic.

And it is to his credit

that he remained a Catholic when it might have been to his material

advantage to revoke. His was the first book of original Gaelic poems to be

published, so with this and his dictionary he staked out for himself a

double claim of honour in Highland literature. Alasdair MacMhaigstir

Alasdair, as they called him, followed the method of the ancient bards,

and composed his songs while he was stretched out on his back with his

plaid round his head and a big stone on his breast. Those who can

appreciate the full flavour of Gaelic verse say that his most beautiful

song is "Morag," written in praise of the Prince. Here are some of the

stanzas in English:

I would follow you

and serve you

Still unswerving in allegiance.

Cling to you with

love compelling,

Like the shell to rock adhering.

With your love my

soul is flaming,

All my frame with longing eager.

They would come, did

you but call them,

Many a stalwart Highland hero,

Who, with claymore

and with shield, would

Cannon's thunder charge unfearing.

These would boldly

gather round you,

Once they found that you were near them.

All the Gael their

love would show you,

Faithful, though the world should leave you.

Alexander Macdonald was

indeed the laureate of the 'Forty-five. Some time after the Rising the

Government passed a law that no man in Scotland must wear any part of the

Highland garb, plaid or philabeg or shoulder-knot, and that no tartan

cloth must be used for coat or greatcoat, under penalty of six months

imprisonment without bail on the first offence; and on the second offence

the penalty was to be transportation to His Majesty's plantations overseas

for seven years. Spurred with indignation, Alexander Macdonald put into

verse the feelings of the Highlander:

Give me the plaid, the

light, the airy,

Round my shoulder, under my arm,

Rather than English wool the choicest,

To keep my body tight and warm.

Thou art my joy in the

charge of battle,

When bright blades are flashing before me!

When the war pipe is sounding, sounding,

And the banners are waving o'er me !

Good is the plaid in the

day or the night time,

High on the ben, or low in the glen;

No king was he but a coward who banned it,

Fearing the look of the plaided men !

Let them tear our bleeding

bosoms,

Let them drain our latest veins,

In our hearts is Charlie, Charlie,

While a spark of life remains !

Even in this rough

translation the plaint of a people can be heard. In 1928, the Clan Donald

put a clock in the church tower at Arisaig as a memorial to the poet, and

the bronze tablet in the wall was unveiled by Mr. Wiseman Macdonald, that

fine old Gael who travelled all the way from Los Angeles for the ceremony.

Although his home is on the other side of the world, this descendant of

Reginald, son of Amie MacRuari, who founded the Clanranald family, has his

roots deep in Moidart, for he is the owner of Castle Tirrim.

The steamer cast off from

the pier at Dalilea; and since Eilean Fhionnan lay around the next

headland, I went up beside the Captain at the wheel to catch my first

glimpse of the island. Little is known about the saint after whom it is

named. His friends called him Finnan the Infirm One ; he is mentioned in

Adamnan's Life of St. Columba; and a fair which used to be held every year

on 18th of March in Moidart was named after him. The local tradition that

he lived on the island is strong, but it is sometimes apt to be forgotten

that many churches of the Celtic period were named after saints who had

never been near the place where their memory has been kept green. It is

almost certain that later missionaries from Iona lived on the island and

preached in the districts around, and it was natural that the Christian

converts and their descendants would wish their bodies to mingle with the

earth of the island they revered. Until long after the days of the

'Forty-five, penitents were ordered to make a pilgrimage to Eilean

Fhionnan; and if the loch was too stormy to be crossed, they knelt on the

shore and went through their religious exercises as though they were

kneeling upon the sacred island.

The steamer rounded the

headland, and from the grey water there uprose a sweet green mound, with

clusters of firs and larches growing upon it; and when we drew nearer I

could see broom and hawthorn and holly and one or two gravestones. The

Captain of the steamer told me that near the ruins of the church there is

a small building which was once used by the Kinlochmoidart family as a

burial-ground. The old square bell rests upon the rough altar stone; it

has lain there exposed to the weather for more than two 'hundred years;

and there is a curse upon the one who removes it. As we left the island

behind us, the picture that built itself up in my mind was that of a

rowing-boat creeping slowly up the loch under a grey sky, with a black

pall covering a coffin on the thwarts, and other boats with mourners

following in procession. This picture faded, and another one from the

distant Celtic centuries took its place: a missionary from Iona, in a grey

hand-woven robe, his head shaven from ear to ear in the shape of a curving

axe-blade, a man with an eager face and burning eyes, standing at the door

of his wattle-hut, gazing towards the east, and then girding up his robe

as he strode down to the coracle drawn up above the water edge.

"There used to be sextons

on the island," said the Captain. "Big Neil of the island was the last of

them. A brave strongman he was. No ghost could frighten Neil."

The Captain had humorous

dark eyes, and I could see that there was a story on the tip of his

tongue.

"One night, some men from

Morven tried to frighten Neil," he went on. "They were a funeral party,

and it was a wild evening, and they could not get to the island until

after dark. They had a lot of whiskey with them, and they would nearly all

be tipsy, I'm thinking. Neil was sound asleep in bed when they came

ashore. They had heard he was brave, but they did not believe he was as

brave as he was called, so they took the coffin up to the door of his hut,

and began to push it across the floor to Neil's bed. One of them was

making groans as if he was the dead corpse. This wakened Neil up, and he

jumped out of bed with a roar and fell over the coffin. But in a minute he

was after the Morven men, and he caught them before they were in their

boat, and gave them the flat of his sword. They went back to Morven with

sore backs, and never more did they say that Big Neil of the island was

not a brave man. I wouldna like Neil's job myself," added the Captain,

with a smile, "and there's few in Moidart that would go near the island in

the night. They say that the soul of the dead keeps watch over the island

until the next burial, and then it is free to leave. But I don't think I'm

believing it," he added, with a shrug, " though some have seen a light on

the island after it is dark."

Soon we were passing Glenaladale, a misty glen

on the north-west shore, where Charles disembarked. The laird, Alexander

Macdonald, was the nephew of Angus Macdonald of Borrodale, the Prince's

first host on the mainland of Scotland. After spending the night with

Glenaladale, who was given his commission as a major in the Clanranald

regiment, the Prince with his attendants and forty of a guard set out

early next morning for Glenfinnan. They drew in to one of the beaches

further up the loch, and the little company had a hasty meal upon a knoll

which is still called the Prince's Mound. The boats grounded among the

rushes at Glenfinnan one hour before noon.

There were nearly a dozen

of us on the little loch steamer that morning, and it looked as if we

might have to spend the rest of the day on board. In spite of the recent

rain, the level of the loch was low, and when we attempted to come up to

the pier we ran aground on a submerged mud bank. The ship had sturdy

engines, but although the crew and indeed some of the passengers helped to

push with poles it seemed that we might stick there until a few more days'

rain had floated us off the bar. After twenty minutes, during which the

noise of the engines rose from a purr to a wild despairing roar, and many

strong men with boat-hooks prodded holes in the Loch Shiel mud, the idea

of lightening the ship-occurred to the Captain. He sent us all ashore in a

rowing-boat, and the cargo after us. And then, with a flutter of the

screw, the steamer floated back into deep water.

I went with the last

boat-load, and could not help noticing how everybody bustled away from the

shore, each on his or her own business. Most of the people, I suppose,

were making for the railway station, where the train for Fort William was

due at six minutes past one. Standing alone with my pack on my back, I

realised I had forgotten to tell the Captain that I had used his vessel as

sleeping quarters a few nights before. Because of his kindly dark eyes,

and the wistful smile that now and then passed over his pale and rather

sad face, I had wanted to make my confession. But now it was too late. The

gentle excitement of running aground, and the effort of helping to get the

vessel off the mud, had made me forget my troubled conscience. Better, I

decided, to let sleeping dogs lie; and turning, I walked slowly along the

path towards the monument that marks the spot where Prince Charles Edward

Stuart raised his father's standard.

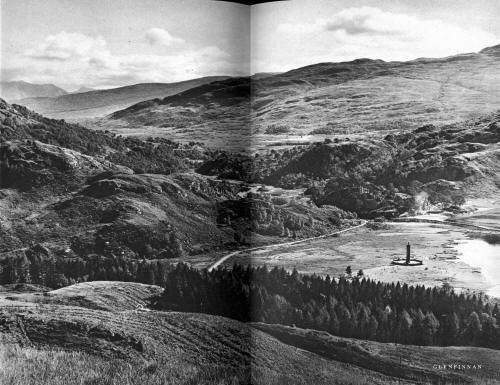

The scene has been

described dozens of times, and this lonely green corner of a lonely loch,

where four deep glens meet, has been the subject of innumerable

engravings, paintings and picture-postcards, most of them entitled "

Prince Charlie's Monument at Glenfinnan." But the familiar column is not a

monument to Prince Charlie. It was built by Alexander Macdonald of

Glenaladale in the winter of 1814 in memory of his own forefathers and

others " who fought and bled in the 'Forty-five." Macdonald died while it

was being erected, and in the words of the inscription, " this pillar is

now, alas ! also become the monument of its amiable and accomplished

founder."

There are three versions of

the inscription on the surrounding wall, in Gaelic, Latin, and English.

The Latin one was composed by the man who invented that vile concoction

known as Gregory's Mixture. Doses of this greyish-pink powder have been

stirred in a little water and administered to the shuddering children of

Britain for nearly a century. No doubt it is a wholesome thing after a

stealthy feast of green gooseberries, but I know it was one of the

nightmares of my childhood. He was as strong as a horse himself, this Dr.

Gregory, which probably accounts for the fact that he seldom tasted his

own Mixture. Indeed, nothing in all his life seems to have disturbed this

serene man, and although he waged many furious battles with his Edinburgh

colleagues, he had a wonderful knack of making them all look ridiculous,

so that he always came out top dog and smiling. This fashionable Edinburgh

physician was anything but a pompous one, for he spent part of his spare

time composing verses of the limerick order, and he had the nerve to print

them for the amusement of his friends. Here is one of his epigrams in

verse:

"O give me, dear angel,

one lock of your hair,"

A bashful young lover took courage and sighed;

'Twas a sin to refuse so modest a prayer

"You shall have my whole wig," the dear angel replied.

But Macdonald of

Glenaladale knew what he was about when he asked his medical man in

Edinburgh to help with the inscription for the Glenfinnan memorial, for

Dr. James Gregory of 2 St. Andrew Square was one of the finest Latin

scholars of his time. Some years afterwards, a stone statue of the Prince

was set on the top of the monument. This was the work of John Greenshields,

a stone mason who took to sculpture at the age of twenty-eight, produced a

bust of George IV which Sir Walter Scott called "a very happy likeness,"

and made what is probably the best statue we have of Sir Walter

himself-the one in the National Library.

From Loch Shiel the

Macdonald monument looks like a dirty stump of tallow candle in a

candle-stick, with a bit of broken wick jutting out at the top; but in the

imagination of many good people, that wick is burning with a flame that

nothing will ever quench. As you go nearer, the octagonal wall around the

foot of the column gives the impression that it encloses a cemetery -

which it does: the cemetery of a young Prince's hopes. I am told that the

chambers inside were designed for use as a shooting-box, and this struck

me as a quaint fusion of ideas. I have heard of a cottage hospital that

was built as a memorial, but I have never heard of a shooting-box. Yet I

have no doubt that the Prince himself would have approved with a laughing

gesture, for few men have ever taken a more hearty joy in what is called

wild sports - "I was bred a fowler," he once said-and no man of his day in

Scotland was a better shot. But I would rather have seen the simple cairn

of stones that long ago used to stand as a memorial at that lochside, with

the shooting-box tucked well out of sight behind the pine trees.

Anyhow, as I gazed on that

bleak thing, with its stained and peeling walls, a horrible depression

began to settle on my mind. The rain had stopped, but the sky was grey,

and the mist made the mountains look hostile. I was cold and hungry, and

as I picked my way through the bog around the monument, I hated the raw

damp smell of the place: it had the very reek of death. For two pins I

would have slunk back to the steamer, and joined the crew at their cocoa

and sandwiches, and returned to Acharacle in the afternoon. Shivering, I

thought of Campbell's peat-fire in the inn sitting-room, and the cheerful

talk of Gillespie and Grant in the evening. I wondered where I would land

before the darkness drew down, and I hated with a deep bitterness the

thought of the day's tramp that was ahead of me.

Some tobacco in the shelter

of the monument wall revived my spirits a little. I thought of the

Prince's arrival there at eleven o'clock in the forenoon expecting to see

a fine crowd of clansmen awaiting him, and I thought of his despair as the

hours passed. The first arrival was James Mor Macgregor, son of Rob Roy

and father of Robert Louis Stevenson's Catriona. He was a man of many

talents, this Macgregor, a treacherous rogue, but a tiger in a battle.

Though the Prince did not know it then, James had recently been a spy paid

by Government. Not that he had much regard either for King George or

anybody else; he was playing for money and a commission in the Black

Watch. But he was ready to hold in with the Prince a the did-on the chance

that the Rising would turn out to be a success. He was taken to the door

of the hut where the Prince sat brooding over the failure of the clansmen

to appear at the place appointed. Charles gave him a courteous welcome,

and James assured him that he could count on the Macgregors to a man.

Another silence for an hour or more. And then came a trickle of

Clanranalds down the rough road among the pine trees on the east, only a

hundred and fifty of them all told under Macdonald of Morar. But there was

better news to come. The Clanranald guards beside the hut caught the sound

of distant bagpipes, and soon along the defile from the north came the

Camerons, with young Locheil at their head, two long columns, three deep,

with a rabble of prisoners between them -prisoners from the two companies

of Scots Royals captured beside Loch Lochy in the first skirmish of the

campaign. It was a brave show these Camerons made coming down beside the

river Finnan from Glen Pean, and although many of them carried no arms -

and indeed a hundred and fifty of them were afterwards sent home-a lot of

them wore the Cameron tartan that Locheil had bought in Glasgow so that on

the day of the rallying his men would appear on the field with fine new

plaids around their shoulders. The Prince's spirits rose. In his

enthusiasm at the sight of these seven hundred Camerons, he ordered the

Standard to be unfurled, and the Duke of Atholl, crippled with rheumatism

and supported by two men, held the staff while the exiled king's

commission appointing Charles as his Regent was read over. After the

ceremony the Prince made what Murray of Broughton called afterwards "a

very Pathetick speech." He did not propose, he said, to talk about the

justice of his father's title to the throne, because his friends around

him would not have come to meet him there on that day if they had not been

convinced of it. He spoke about the noble example of their predecessors,

of their country's honour, and the protection of "a just God who never

fails to avenge the cause of the injured," and he did not doubt that they

would bring the affair to a happy issue. He then retired to his hut.

A little later, other

groups arrived, three hundred Macdonells from Lochaber with Keppoch at

their head, and some MacLeods who had come against the orders of their

chief-a man who had promised to join the Prince, and was in fact sending

to the Government what information he could glean about the progress of

the Rising. According to Aeneas Macdonald, a group of ladies and gentlemen

had assembled to watch the ceremony at Glenfinnan, among them jenny

Cameron.

Will the "notorious" Jenny

Cameron never be allowed to sleep in peace? During the campaign yarns flew

around the country that she was the Prince's mistress. Before he had left

Scotland, no less than three ridiculous books about her life had been

published, and her name was bandied about in pamphlet and newspaper as a

Scarlet Woman. One of these books sets forth that she was in the habit of

masquerading in a man's clothes, and had been the queen of a band of

robbers before she became the Prince's mistress at Glenfinnan. Even in Tom

Jones, one of the greatest novels in the English tongue, she is referred

to as Charles's paramour, and the fable has persisted steadily to this

day. A few years ago, at a Scottish Exhibition in London there was a print

entitled "Bonnie Jenny Cameron of Locheil," and in the catalogue she was

described as "Mistress of Bonnie Prince Charlie." She was certainly not a

Cameron of Locheil - her father was Cameron of Glendessarry - and I doubt

if there is a shred of evidence that she ever exchanged a word with the

Prince in her life. At the time of the Rising, she was between forty and

fifty years of age, "a genteel, well-looking woman with a pair of bright

eyes and hair as black as jet . . . and very agreeable in conversation." A

keen Jacobite, she sent the Prince a gift of cattle, and during the

campaign she managed her brother's estates in Strontian while he served as

an officer in the Highland army. The rumour that she was present at

Glenfinnan no doubt started the scandal, and Grub Street did the rest.

Now, it happened in the

following February that an Edinburgh milliner called jenny Cameron set out

to visit a relative who lay wounded in the Prince's camp near Stirling.

Cumberland's troops arrested her, and Cumberland himself expressed delight

at her capture. Convinced that the famous jenny Cameron had fallen into

his hands, he decided to use her as evidence against the rebels, with the

result that the poor milliner was locked up in Edinburgh Castle for eight

months, when she was released on bail. Her imprisonment was the best piece

of publicity she had ever received, for all Edinburgh crowded to buy her

ribbons, gloves, and fans.

But there was yet another

jenny Cameron, a crazy old woman who years later dressed herself in men's

clothing, and went hobbling about Edinburgh on a wooden leg begging for

alms, assuring the credulous public that she had been the Prince's

mistress in Scotland. The poor old maniac died in Edinburgh Infirmary, but

the myth has been kept alive by babbling tongues for nearly two centuries,

and will no doubt live by the same medium for several centuries more.

At Glenfinnan, the Prince

had certainly neither time nor inclination for dalliance. For two days he

remained at the head of Loch Shiel, supervising a multitude of details and

sleeping in the hut at night. One of his officers said afterwards that

during all the months Charles was in Scotland he was never more happy than

during those two busy days.

I climbed the hill to the

Catholic chapel that stood above the monument. Behind it, sweeping up to

the horizon, there was a wood of many trees, Scots Pine, Austrian Pine,

Douglas Fir, Larch, Cedar, Cypress and others I cannot put a name to. The

walls of the chapel were built of a light grey granite, and the west door

looking down the loch stood open. I went in, and entered a new world.

That small chapel, with its

white-washed walls and coloured reliefs, its plain wooden roof and

unvarnished benches, its clean-scrubbed wooden floor and the little loft

with its narrow corkscrew stair, struck me as uncannily beautiful. A cool

clear light, like the light on a pale Arctic sea, dwelt in that place. A

rich red hanging behind the altar was the only bit of high colour, and it

drew the eye back to it again and again. I sat down on the bench beside

the door and wondered who had built this chapel-who had made it so

perfect, so austere, so white and clean and cool. To eyes weary of these

green barbaric hillsides and the zigzag of the horizon, here was a place

so orderly and simple that it was a sweet lenitive to the mind. A brass

tablet on the wall has the words : Charles Edward Stuart, R.I.P.

I had climbed up to the

chapel half afraid that I might find it hideous with tinsel and paint, and

so noisily crowded with things that it would look as if there was no room

for the congregation, an impression one often gets in Catholic churches on

the Continent. But the silence and the lovely fitting emptiness of this

chapel at Glenfinnan had an effect on me that it is impossible to

describe.

I lingered at the door,

which is always open, and looked past a clump of larches to the blue-grey

water of the loch below and the jagged hills beyond that shut off the

mountains of Ardgour and Morven. Turning, I gave a final glance into the

chapel, with its white walls and bare benches and that red splash of

colour behind the altar, then I hurried down the path. |