|

THE Church of the parish of

Kinkell, in Strathearn, was dedicated to St. Bean, the Bishop of Murtlach,

who suffered martyrdom in the tenth century, and became one of the latest

saints in the Scottish Kalendar. It was appropriated to the Abbey of

Inchaffray by the foundation charter of Gilbert, Earl of Strathearn, and the

cure was served till the Reformation by a vicar appointed by that house.

The lands of Kinkell belonged

to the Earldom of Strathearn. On the 6th of December, 1406, Patrick, Earl of

Strathearn, with the consent of Euphemia, his wife, granted an annual rent

of five pounds Scots from their two towns of Kincell, in Perthshire, to

Euphemia, daughter of Sir Alexander de Lindsay of Glenesk, which was

confirmed by the Duke of Albany, as Regent of Scotland, on the 15th

December, 1412.

Little Dunkeld was commonly

held to be the "Terrible Parish" in Scotland referred to in the old rhyme;

but the real locality is that of the parish of Kinkell, in Strathearn, the

mistake in identity having arisen in the similarity of names. The lines are

as follows:—

"Was there e'er sic a parish,

a parish, a parish;

Was there e'er sic a parish as that o' Kinkell?

They've hangit the minister, drooned the precentor,

Dang doon the steeple, and drucken the bell."

The explanation given of the

circumstances which gave rise to the rhyme is that the minister had been

hanged, the precentor drowned in attempting to cross the Earn from the

adjoining parish of Trinity-Gask, the steeple had been taken down, and that

the bell had been sold to the parish of Cockpen, near Edinburgh.

The story of the minister's

career is a sad one. Mr Richard Duncan had his degree of A.M. from the

University of Edinburgh, 2nd July, 1667; was licensed by Alexander, Bishop

of that Diocese, 10th April, 1673, and ordained minister of Kinkell between

16th September and 11th November, 1674.He was in good repute for some years,

but came to a melancholy and untimely end. He appears not to have got on

well with his heritors and kirk-session. The churches of Trinity-Gask and

Kinkell had both got into a ruinous condition, and required rebuilding. On

13th April, 1680, the Bishop and Synod instructed Mr Duncan to use all

lawful endeavours to deal effectually with the heritors for rebuilding the

churches, and if, after endeavour he could not prevail, to raise letters of

horning against them. He reported to the Synod on 12th October, 1680, that

notwithstanding he had used all endeavours with the heritors for rebuilding

the said churches, and persons of honour had appeared very willing, and that

the Marquis of Athole was most willing to assist to the doing of the said

work, yet divers of the rest of the heritors were refractory, and that,

therefore, he had raised letters of horning against them. The Bishop and

Synod appointed a deputation, in name of the Synod, to go to the Marquis of

Athole, to render their thanks to his Lordship for his willingness to do so

good a work, and humbly to entreat that his Lordship would continue his

Christian resolutions till the work be perfected, as also he would take his

own prudent way for moving the rest of the heritors thereto. And in case the

said work should not be gone about and perfected, they ordained Mr Duncan to

proceed in using legal diligence for effectuating the same, and to report to

the next Synod.

In addition to his complaint

of the unwillingness of the heritors to rebuild, Mr Duncan reported to the

same Synod that the heritors and kirk-session of the parish of Kinkell had

caused cut down some ash trees growing in the kirkyard, had sold them, and

given the money thereof for casting of the bell, without the consent of

their present minister, the said Mr Richard Duncan. The Bishop and Synod

deferred this matter until the next Synod.

At next Synod, held on 16th

October, 1681, the Laird of Machany presented and gave in to the Bishop and

Synod a supplication, subscribed by himself and most part of the heritors

and elders of the parish of Kinkell and Trinity Gask, against Mr Richard

Duncan, minister of the said united churches, representing his gross

ignorance in re-baptising a child, and other gross, rude, and scandalous

offences and misdemeanours commited by him. This supplication was taken into

consideration and referred until a future meeting of Synod, with a view to

think on such overtures as might be for the good of the parish, and to keep

union and peace amongst them.

Mr Duncan was desired by the

Bishop to acknowledge his faults, but he seemed to be somewhat averse to do

so, and so gave little or no satisfaction therein to the Bishop and Synod.

No record seems to have been kept of the proceedings or the adjourned

meeting at which the complaint against Mr Duncan was to be considered. It

appears, however, that Mr Duncan was deposed before the 1st of February,

1682; but worse than deposition was in store for the minister of Kinkell.

Lord Fountainhall gives the following account of his melancholy end :—

"June 6, 1682.--One Mr

Duncan, a minister in. Perthshire, is condemned to death by the Ear! of

Perth, as Stewart of Crieff, for murdering an infant begotten by him with

his servant maid, it being found buried under his own hearth-stone. He was

convicted on very slender presumptions, which, however, they might amount to

degradation and banishment, yet it was hard to extend them to death,"

The name of the maiden

referred to was Catherine Stalker.

It is said that a reprieve

was obtained in his favour through the interest of the future Lord

Chancellor, and the messenger was observed on the way by Pitkenony, near

Muthill, about two miles distant. He arrived about twenty minutes too late,

which caused a deep feeling of sympathy in the minister's fate.

Tradition further says that

Mr Duncan, when led forth for execution on the "kind gallows of Crieff,"

avowed his innocency of the crime, and declared that after his being thrown

oft, a white dove would alight on the gallows in token thereof, and that

this, accordingly, took place. There is a notice of the behaviour of Mr

Duncan at his execution, from which it appears he engaged in devotional

exercises, and denied his alleged crime to the last. It occurs in the

"Relation of rare providence that befell a young child, daughter to a

husbandman or farmorer, whose name is Donaid M'Grigor, dwelling in the

parochin of Monzie, living in the Sheriffdom of Perth." the occurrence being

1683—that "there was a Confurmist minister executed for murder, which he

denied to the last that he had any accession to it. She was desired to ask

if he had any hand in the child's blood who was murdered. It was answered

that he was guilty of that murder; then, said she, how can that be, for I

saw him pray and sing a psalm at his death. To this it was answered—

Notwithstanding, that doth riot make any innocence of these things which

they had done. Then she said she heard him deny it. To this, answer it was

no good that bade him do that."

Kinkell was long ago united

with the parish of Trinity-Gask, but to provide ordinances the minister had

to officiate on alternate Sundays at Kinkell. On one of these occasions the

precentor, in crossing the river from Trinity-Gask, is said to have been

drowned.

Notwithstanding the exertions

of Mr Duncan, backed by the authority of the Bishop and Synod, and the

compulsitors of the civil law, the churches of Kinkell and Trinity Gask were

not repaired or rebuilt until some years after Mr Duncan's death. In the

record of the Synod we find on 12th April, 1686, there is the following

entry —"The Bishop and Synod ordains the brethren of Ochterarder that they

may delegate some of their number to wait upon and converse with the Bishop

at the down-sitting of the Parliament, or at some other convenient time,

that they may speak with the heritors of Kinkell and Trinlty-Gask anent the

reparation of the two ruinous churches."

The Church of Kinkell appears

to have been rebuilt from its foundation, and corresponds with the style of

building at the time of the Revolution. It has no steeple, and this want may

be explained by the recorded reluctance of the heritors to provide a place

of worship for the parish. The part of the rhyme in reference to the steeple

may have arisen from the demolition of the previous edifice with its steeple

when the new church was built.

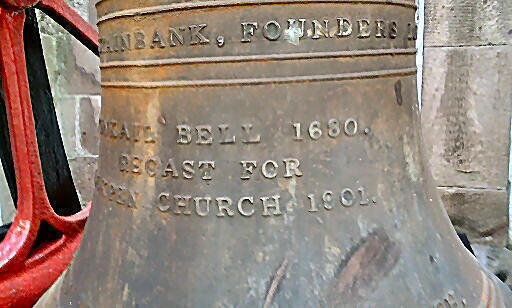

The fourth charge of the

indictment in the rhyme referring to the bell of the church has been

strangely verified. The tradition is quite familiar with the folks in

Cockpen in regard to the bell having been sold to that parish. The

inscription on the bell hanging in the steeple of Cockpen Kirk is as

follows:— "This bell belongs to the Parish of Kinkail"; and immediately

beneath—"Jasper van Erpecom me fecit, 1080." The bell was cast on the

Continent in 1680 for the parish of Kinkell, and was brought to Cockpen not

later than 23rd October, 1708. Two money payments appear from the

kirk-session records of Trinity-Gask in connection with it, the one on the

above date, and the other on the 29th May, 1709, in which it is called "The

great bel." This bell was used in the old kirk of Cockpen, the ruins of

which still stand a little to the south of Dalhousie Castle and adjacent to

the site of Cockpen House, the residence of the Laird of Cockpen. When the

new parish kirk was built in the year 1820, about a mile farther north, near

the village of Bonnyrigg, the bell was transferred to it, and is still rung

every Sunday announcing public worship. It may be remarked that the date on

the bell coincides with the fact that the price of the trees in the

churchyard was devoted towards the expense of its casting, and also shows

that it had been used in the steeple of the old edifice, and was not

required in the new one, where no steeple had been erected. The price of the

trees was, as we have seen, devoted to the purchase of a bell, but the price

of the bell itself, according to the rhyme, was not similarly devoted " It

is to be hoped, however, that this additional scandal may have only existed

by a poet's licence.

Mr Hill Burton in his History

of Scotland alludes to the rhyme as having reference to the parish of Little

Dunkeld, and this corresponds with the way in which it is generally, though

not invariably, recited. But the undoubted fact that the minister of Kinkell

was executed, even though all the other circumstances cannot now be

verified, shows pretty conclusively that Kinkell is the parish to which it

is applicable. Nothing can be adduced to connect Dunkeld with such a

tragedy. The turbulent relations between the Bishop cf Dunkeld and the

people of his Diocese were in pre-Reformation times, and could not have

given rise to the words of the rhyme which refer to the modern Presbyterian

Church and its officials of minister and precentor.

Ian Bee is the Beadle of Cockpen Parish Church

and in August 2016 he sent me an email which included...

"I am the beadle at the above church and, with my son, have spent two days

painting the ironwork which supports the "Kinkail Bell" . Endeavouring to

find out more about the bell (there is a large amount already known), I came

upon your site and found much, much more which may be of interest to our

members."

He then sent me in some pictures of before and after the painting which I

include below...

|