|

AT Invergarry station we

reach the west end of Loch Oich, which forms the highest point of the

Caledonian Canal, little more than a hundred feet above sea level. Looking

back across the little strip of land that separates the waters of Loch Oich

from those of Loch Lochy, we see a stream coursing down the hillside which

is one of those curious instances met with in watersheds where a man with a

spade might in a few moments turn aside the waters of the stream so that

instead of being discharged into Loch Linnhe on the west coast they would

ultimately find their way into the German Ocean, far on the other side of

Scotland.

A similar example is found in

the headwaters of the Clyde and Tweed, it being quite a question whether the

stream will flow east or west, and in times of spate salmon fry are

frequently washed from the headwaters of the Tweed into the upper reaches of

the Clyde, above the Falls of Cora.

In the present instance a

very practical old lady turned this singular formation of nature to good

account. She lived just on the march or boundary between Locheil and

Glengarry, the dividing line being formed by the stream. As often as the

Cameron factor came to collect his rent he found the stream flowing merrily

between him and the old woman's house, and whenever she saw Glengarry's

officer approaching on a similar errand she diverted the water to the other

side of her little property and defied him to lift his dues. By this

ingenious plan she maintained her house and land for a long number of years

free of all rent and taxes.

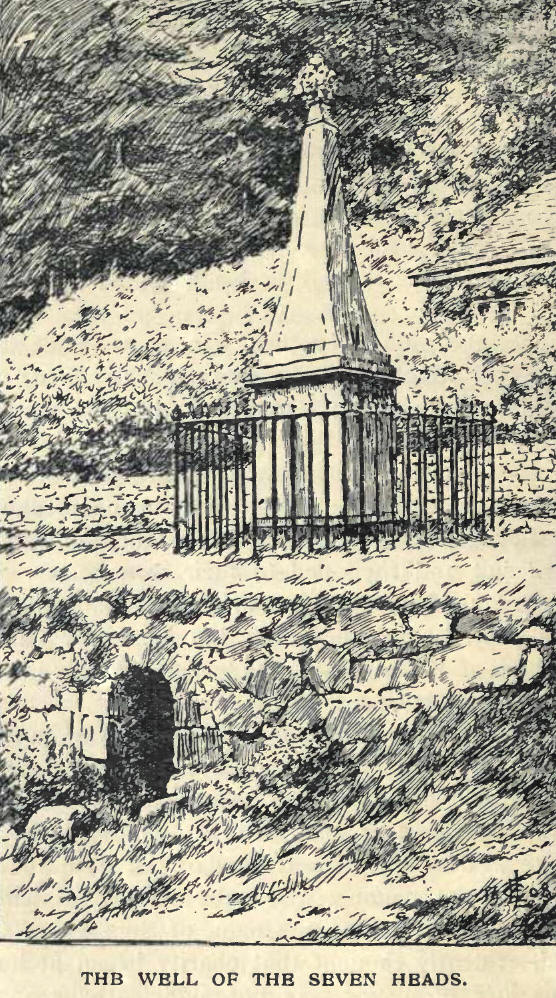

Directly opposite Invergarry station on the edge

of the loch there stands a small monument commemorating one of those deeds

of blood so common in the Highlands. Beneath the monument there bubbles up a

little spring of clear, cold water, whilst the top of the shaft is crowned

by a hand grasping seven heads transfixed with a dagger. Few stories are

better known in the Highlands than this tale of the seven heads, yet seldom

has so well-known a fact been confused with such a mass of conflicting

details. The case is

characteristic and throws a singular sidelight on the manners of the north

at the time of the Restoration.

One of the chiefs of Keppoch had sought a bride

outside the limits of his clan and had married "a woman from the south," as

she was contemptuously styled, one of the Forresters of Kilbaggie, in

Clachmannan. The two sons of this marriage were sent abroad to be educated

in Rome, and while there the father died, leaving his brother in charge of

the clan till such time as his son should have completed his course and

attained his majority. Five years after their father's death the two youths,

Alexander and Ranald, returned to Lochaber and took up the leadership of the

clan. With all the

enthusiasm of youth and a liberal education, Alexander set about improving

the condition of his people and made it his endeavour "to drive all thieves

and cattle-lifters from his boundaries." This running counter to all the

dearest traditions of Lochaber brought a certain amount of discontent and

disaffection in its wake. The uncle, Alastair Buidhe, an unscrupulous and

ambitious man, turned this dissatisfaction to account and fanned the spirit

of rebellion till a widespread conspiracy was formed against the youthful

chieftain. Finally the head of one of the minor septs, who had long

cherished a secret grudge against the family of the chief, set out one night

with his six sons and some other retainers, and having waded the river below

Keppoch Castle, entered the house "with the water of the Spean still in his

shoes." Finding the young chief defenceless in his bed, they plunged their

dirks into his body, killing him on the spot.

Ranald, the younger brother chanced to be out at

the moment of attack, and hearing of the disturbance hastened to the rescue

; but on entering the castle he was instantly seized and overpowered. He

cried to his uncle, Alastair Buidhe, who was present, to assist him, but

instead of trying to defend him the uncle plunged the first dagger into his

breast. The other conspirators followed suit and then fled to their own

homes. The clansmen quickly gathered, and John Macdonald, the famous poet,

better known as Ian Lom, the bare or biting bard of Keppoch, had the bodies

carefully laid out and honourably buried.

No one thought of seeking redress at the hands

of the Government, and had it not been for Ian Lom the incident would

probably have passed unavenged. As it was, the bard poured forth such a

torrent of bitterest invective against the perpetrators of the deed that he

had to fly the country and take refuge in Kintail. Glengarry, though loving

the name of Superior of Clan Donald, evidently thought that charity began at

home, and his love of justice was not sufficiently strong to make him risk

burning his fingers by attempting to call the culprits to account.

and bring the murderers to justice. The

conspirators expected an avenging party to come from Glengarry, and kept a

sharp look out upon the castle from a little bothy on the summit of one of

the hills of the southern range. But Ian I.om skillfully outwitted them, and

brought the little party of Islesmen up the valley of the Spean to Inverlair,

where they surprised the father and six sons in bed. The sons were instantly

dragged out and slain and the house set on fire. In the scuffle the father

almost escaped unnoticed, when Ian Lom cried out, "the six cubs are here but

the old fox is still in the den." At once a number of men dashed into the

blazing house and dragged out the father, dispatching him on the spot. The

bard then severed the heads from the bodies and putting them into a sack

carried them by a circuitous route to Invergarry. Before reaching the castle

he washed his gory trophies at this little spring. Then, after taunting

Glengarry with bitter sarcasm on the inactivity which left the avenging of

this foul murder to his distant kinsman, the poet laid the seven heads at

his feet, and they were afterwards buried in a little glade not far from the

present mansion house of Invergarry.

It is worthy of note that the mother of these

murderers on whom the beardless bard executed such summary vengeance was his

own sister. This

monument was erected and the inscription upon it invented by Colonel

M'Donell, the last chief of Glengarry, in 1812.

Some years ago an antiquarian enthusiast in Fort

William sought to prove the truth of this tradition, and dug up the mound at

Inverlair where the bodies were supposed to have been buried. The skeletons

were found buried without a coffin, whole and entire, excepting that each

one lacked a skull, thus confirming the main facts of the story current in

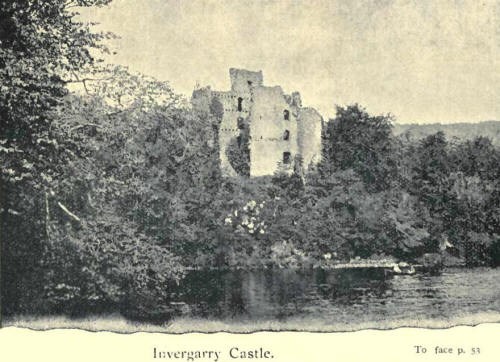

Lochaber. About half

way down Loch Oich we come to the famous old Castle of Invergarry. It stands

perched upon a rock rising sheer out of the waters of the lake, and in olden

times was a position of great strength. The rock is known as "Creag an

Fhithich," or the "Raven's Rock," and this used to be the war-cry of the

clan.

The castle has an interesting history. It has

been built again and again on the present site and as often destroyed, till

finally it was burnt by Cumberland in 1745 and never restored.

In 1727 an English company, enticed by the

plentiful supply of timber in the district, set up iron smelting works in

Glengarry. The manager, finding the castle in ruins as a result of the

loyalist rising in 1715, roofed over the walls and took up his abode there.

But the clansmen were indignant at this desecration, as they deemed it, of

their chief's ancestral hall, and they fell upon the misguided "Sassenach,"

who narrowly escaped with his life.

During the troublous times of religious

persecution, Glengarry was one of the great centres round which the

Catholics of the north rallied. On account of its close connection with the

Catholic district of Knoydart, many of the Irish priests who came from Spain

and elsewhere to minister to the wants of their co-religionists in the

Western isles found their way to this district. The Hardwicke Papers tell us

that the Clanranalds were

"always Popish," and "the people of all ranks

here are much better acquainted with Rome, Madrid and Paris, than they are

with London or Edinburgh." As early as 1670 a Catholic school was erected in

Glengarry, one of the very first established in the north.

During the time the castle remained in the hands

of the M`Donells persecution was unknown, but when it fell into the hands of

English soldiery persecution was attempted and many a priest was done to

death in the vaults of the ancient building.

As mentioned above, excepting the few square

feet of ground in the churchyard of Kilfinnan, the narrow compass of this

rock crowned with its ruined walls is all that now remains to the ancient

clan of the wide lands that once belonged to the M'Donells of GIengarry.'

Rev. Alex. Stewart tells a pretty tale of how

this rock came to remain in possession of the clan when all the rest of the

estates were sold. A

great friend of Glengarry who was paying him a visit came down to breakfast

one morning and found the chief with a letter in his hand and a look of

blank despair upon his face. As his friend entered the room Colonel M`Donell

rose and stretching out his hand greeted him warmly with the words: "Welcome

for the last time to Glengarry's house and board." His friend asked him in

amazement what this meant. "It means," said the Chief, "I have just had a

letter, and the estates must be sold to meet the claims upon me." "Is it

must?" quoth the friend. "Yes, must, there is absolutely no alternative."

"Then if the estate must go why not keep the castle with the Raven's Rock,

then with your back to the crag in the words of your favourite Fitz-James

you can still cry out:

"Come one, come all. this rock shall fly,

From its firm base as soon ayI"

With tears in his eyes the ruined chieftain

thanked his friend for his timely counsel, and in a few days the whole

estate save only this lonely crag had passed into the hands of strangers.

This Colonel Alastair Ranaldson M'Donell was a

notable character. An intimate friend of Sir Walter Scott, to whom he

presented Maida, the deerhound of which Scott was so proud, he shot a

grandson of Flora Macdonald in a duel, disputed with Clanranald the

supremacy of the Macdonalds, was the last Highland chieftain who travelled

the country with his "tail," married a daughter of Sir William Forbes - a

strong claim on Scott's affection—and after living a century behind his

times, died in 1828. He was the grand-nephew of Alastair Ruadh M'Donell,

alias Jeanson, alias Roderick Random, and now perhaps best known as "Pickle

the Spy." Scott .devotes a few lines of his journal to Colonel M'Donell. "He

seems to have lived a century too late, and to exist in a state of complete

law and order, like a Glengarry of old whose will was law to his sept.

Warmhearted, generous, friendly, he is beloved by those who know him. . . .

To me he is a treasure." With him passed away the final link that connected

the ancient Highland dispensation with the modern, and when he was carried

to the grave was seen for the last time the full accompaniment of Highland

costumes on such occasions.

It was and is still a point of honour amongst

the Highlanders amounting almost to superstition that a man should be buried

in the grave of his fathers, no matter how far he might have strayed from

home. This commonly entailed long journeys of twenty or thirty and

oftentimes more than a hundred miles. As there were no roads the coffin was

shouldered all the way, streams and rivers having frequently to he forded.

Yet by relieving one another in regular relays the distance was covered in a

surprisingly short space of time. Hence it came to be a disgrace in the

Highlands to be carried to the churchyard in a hearse. When Glengarry died

there was some question of sending a hearse from Inverness, but the clansmen

rose and said it would never enter the glen; "no, it was by the hands of the

people and shoulder high that Glengarry should be borne to the grave, and

they would never see- Mac-mhic-Alastair carried to Kilfinnan in a cart."

The pipes always attended every funeral to

inspirit the bearers on their march and to show honour to the dead. But on

such occasions the piper invariably followed the bier, just as at marriages

he played in front of the procession; the reason of course being that the

corpse was carried feet first and the place of the piper was at the head. If

the deceased were a person of note the clan standard was carried furled in

front of the coffin, while directly behind the bier a space was cleared for

the piper by four clansmen with drawn swords.

The inevitably early start entailed by the

distances to be traversed accentuated the custom of wakes, so common in all

northern countries. As

is well known wakes originated in the custom of watching through the night

to say prayers for the dead, and the word is merely a translation of the

familar term "vigil," so frequently used in the Catholic Church to-day.

Hospitality demanded that refreshments should be offered to the watchers,

and in time this degenerated into the carousal which we find as a blot on

our English statutes as early as the tenth century. In the Highlands be it

said, anything like intemperance at these wakes was practically unknown till

comparatively recent times. Drunkenness was never a national vice of the

Highlanders as of the English. Sir Walter Scott's well known description of

a Highland festival in the "Fair Maid of Perth" may be taken as in the main

true to life. "Even the liquor itself," he says, "did not seem to raise the

festive party above the tone of decorous gravity." Whisky, now so intimately

connected with the idea of the Highlands, seems to have been quite unknown

in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and its introduction was very

gradual. Brandy imported from France was far more common, while the ordinary

alcoholic liquors in use were claret and the light Rhenish wines. Any

adulteration of these wines in Scotland was punishable with death as early

as 1482. In the

Highlands at the present day it is the custom for women never to follow the

funeral. In olden days the womenfolk who had attended the wake used to

follow as far as the first burn, where, after partaking of a light

refreshment, they returned, and the cortege proceeded on its way. Frequently

two men used to walk a few hundred yards in advance and offer refreshments

in the name of the deceased to any they met on the way. This parting cup was

intended as a last act of hospitality—always a darling virtue with the

Highlanders—and carried with it a tacit obligation of offering a prayer for

the person who was being carried to the grave.

An eye-witness describes the scene at the

funeral of Colonel M'Donell.

At daybreak columns of the clan streamed down

from every glen, each body being headed by the pipes. Arrived at the castle

they lined up on the lawn in their various companies, and in the large open

space before the door was pitched the great yellow banner of the clan

surmounted by a spreading bush of heather, the badge of Clan Donald. Shortly

after, the doors swung open and in the gloomy hall beyond appeared the

coffin with four stalwart Highlanders bearing flaming torches at each

corner. Waxen tapers fixed between the antlers upon the whitened stags'

skulls that surrounded the hall cast a weird light upon the tartans and

armour covering the walls. The "ceann-tigh," or heads of the cadet families,

were already assembled, and as they lifted the coffin Glengarry's piper, who

had taken his stand beside the colours, blew up the march "Cille-Chriost."

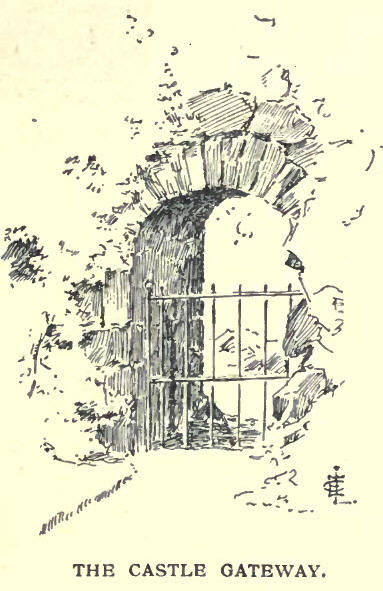

It was a terribly wild day and a thunder storm

was raging as the procession moved off. Passing the barbican of the old

ruined castle a brilliant flash of lightning lit up the sky followed by a

crash of thunder. As the roar of the thunder rolled round the hills, Allan

Dall, the old blind bard of the chief, burst forth into a piteous wail: "Ochon,

ochon, ochon, Mhac Mhic Raonail cha a-fhaic mi thu cha maic mi thu a-chaoidh!

A laimh dhcas a' ghaeil!" Then waving his bonnet towards the sky he broke

into a wild lament, calling the heavens and the storm to the grave of his

chief. In a few moments the refrain was taken up by all present, and a deep

surge from two thousand voices rolled forth the chorus to the skies.

"Is sona 'Rhean-hamns' air an cinch grian,

Is beannaicht' an corp air an tuit an fhras.''

"Happy the bride that the sun shines on,

Blessed the corpse that the rain rains upon."

I3y the time the procession reached the

graveyard at Kilfinnan the stream was swollen to a roaring torrent, and

there was no bridge across the burn as there is today. But the Highlanders,

well used to fording streams on such occasions, plunged fearlessly into the

flood. When the coffin reached mid-stream it seemed for a moment as if the

hearers with their charge would be swept away, when Angus, the chief's

eldest son, flung out the war-cry from the other side: "Lamb dhearg

hhuadhach Chlann DhomhuiIl!" Those behind pressed eagerly forward, and the

bier, borne by the strong arms of the willing clansmen, safely won the

further bank. A few minutes later and the Iast Chief of Glengarry lay side

by side with his famous ancestor, "Black John " of KiIliecrankie, beneath

the green sod of that little plot of ground, all that now remains to link

his family with the glens and the people he loved so well.

As the train leaps into the little tunnel at the

end of Loch Oich, the castle passes out of sight, but the high road clambers

over the summit of the crag and affords a magnificent view of the old castle

and its grounds. An interesting event was connected with this rock which may

he worth relating.

Shortly after the battle of Killiecrankie a

detachment of "Red Coats" was dispatched from Inverness under command of

Captain Ramsay with orders to take Glengarry Castle. On reaching the east

end of Loch Oich, in the absence of any bridge, it was found impossible to

cross the river, and the only way of approach lay in passing round the west

end of the lake. Ramsay was well known in the district as a daring and

resourceful officer, and nothing daunted he set about accomplishing his

purpose. Glengarry on the other hand was determined to crush him if possible

before he could reach the castle. As the little troop won the top of the

crag, Glengarry and his armourer were watching their advance from the castle

window. Alastair, the "armourer," had long vaunted his prowess in the use of

some small pieces preserved in the castle tower. Glengarry, half in jest,

turned to the old man and said, "If there is any good in those pop-guns of

yours bring down the officer who is leading that band of 'Red Coats,'"

pointing, as he spoke, to Ramsay who was marching at the head of the column.

``I will not answer for them all," replied the armourer with grim

determination, "but this 'cuckoo' will do a work which will surprise you,."

and unhitching one of the weapons he levelled it across the window-sill.

Just as he was in the act of taking aim Ramsay passed to the rear of the

column, but Glengarry with his fierce Celtic impatience cried, " Never mind

him, never mind him, blaze away at the head of the troop." The report rang

out, and the next moment a confused rush at the front of the troop told that

the armourer's pet weapon had carried death into the ranks of the

assailants.- "Well done, well done, Alastair," cried Glengarry patting him

on the back, "the 'cuckoo' has spat upon them," but the old armourer without

answering a word calmly took down another of the pieces from the wall,

carefully primed it, and laid it across the sill. While he was taking

aim Captain Ramsay hurried to the head of the

troop to see what had happened. Once more the report rang through the glen,

and Ramsay fell a huddled mass at the head of his men. Frantic with

excitement, Glengarry turned to his faithful follower and cried, "Bravo,

Alastair, the Ramsay is as good as the 'cuckoo'; little did I think that

your southern toys could compare with my claymore." The soldiers in

confusion and alarm hurriedly picked up the corpses of their officer and

comrade and in all haste made the best of their way to Inverness. Just here

a glimpse may be caught of Aherchalder Mansion, a shooting lodge on the

Glengarry estate, which stands on an eminence to the right of the railway

and takes its name from the burn which runs at its foot. From Aberchalder

station a short run brings us to the village of Fort-Augustus. The flat

peat-moss that is crossed on the way is known as "Montrose's Mile," for it

was here that the intrepid warrior pitched his camp just before the battle

of Inverlochy. In a few minutes we pull up at Fort-Augustus which will

require a chapter to itself.

|