|

IT is a mistake to suppose that even among barbarous tribes,

such as the Ngoni, all their customs are bad. There were, before Christian

teaching began to influence them, many things which were admirable. Those

traits of character and customs so readily seen by strangers, the

observation of which has so often led travellers to believe that the state

of the untutored savage was happy, free and good, are nevertheless found

alongside lower ways of living, and a grossly immoral character, which are

not only the obstacles to Mission work but its raison d'etre. It is not our

purpose, meantime, to state or explain fully the customs of the people, all

of which have an interest from the anthropological point of view, but to

present a brief sketch of those which stood out as hindrances to the

progress of our work, and which, being bad, had to succumb to the influences

of the moral and spiritual teaching of the gospel. There are many customs so

grossly obscene that we cannot enter upon a statement of them. I avail

myself of a letter from my colleague, Rev. Donald Fraser, which he recently

sent home, describing what he witnessed in an out-lying district of

Ngoniland in connection with the initiation customs at the coming of age of

young women.

“Leaving these bright scenes behind, I moved on west into

Tumbuka country to open up new territory. But scarcely had I turned my back

on Hora when I began to feel the awful oppression of dominant heathenism.

For a few days I stopped at the head chiefs village, where we have recently

opened a school. The chief was holding high days of bacchanalian revelry. He

and his brother and many others were very drunk when I arrived, and

continued in the same condition till I left. Day after day the sound of

drunken song went up from the village. Several times a day they came to

visit me and to talk : but their presence was only a pest, for they begged

persistently for everything they saw, from my boots to my tent and bed. The

poor, young chief has quickly learned all the royal vices—beer-drinking,

hemp-smoking, numerous wives, incessant begging. I greatly dread lest we

have come too late, but God’s grace can transform him yet.

“When we left Mbalekelwa’s we marched for two days towards

the west, keeping to the valley of a little river. Along the route,

especially during the second day, we passed through an almost unbroken line

of Tumbuka villages. At every resting-point the people came to press on us

to send them teachers, and frequently accompanied their requests with

presents. When at last we arrived at Chinde’s head village, we received a

very cordial welcome. Chinde (a son of Mombera) did everything he could to

convince us of his unbounded pleasure in our visit. For three or four days

we stayed there, and were overwhelmed with presents of sheep and goats, and

with eager requests for teachers. Leaving this hospitable quarter, we had a

long, weary march through a waterless forest, in which we saw the fresh

spoor of many buffaloes and other large game, and heard a lion roaring in

front. Late in the afternoon we reached Chinombo’s and remained for other

three days. Here again, we were well received and loaded with presents.

“This whole country to the west is still untouched. That the

people are eager to learn is evident from their urgent requests. That they

sadly lack God, and are living in a dreadful degradation, became daily more

and more patent. I cannot yet write as an inner observer. Tshi-tumbuka, the

language spoken there, I am only now beginning to learn. Yet the outer

exhibitions of vice and drunkenness and superstition were only too painfully

evident.

“Often have I heard Dr Elmslie speak of the awful customs of

the Tumbuka, but the actual sight of some of these gave a shock and horror

that will not leave one. The atmosphere seems charged with vice. It is the

only theme that runs through songs, and games, and dances. Here surely is

the very seat of Satan.

“It is the gloaming. You hear the ringing laughter of little

children who are playing before their mothers. They are such little tots you

want to smile with them, and you draw near; but you quickly turn aside,

shivering with horror. These little girls are making a game of obscenity,

and their mothers are laughing.

“The moon has risen. The sound of boys and girls singing in

chorus, and the clapping of hands, tell of village sport. You turn out to

the village square to see the lads and girls at play. They are dancing ; but

every act is awful in its shamelessness, and an old grandmother, bent and

withered, has entered the circle to incite the boys and girls to more

loathsome dancing. You go back to your tent bowed with an awful shame, to

hide yourself. But from that village, and that other, the same choruses are

rising, and you know that under the clear moon God is seeing wickedness that

cannot be named, and there is no blush in those who practise it.

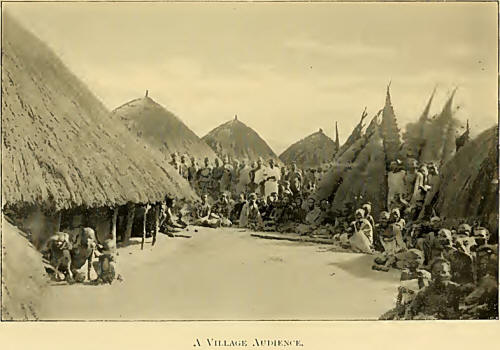

“Next morning the village is gathered together to see your

carriers at worship, and to hear the news of the white stranger. You improve

the occasion, and stand, ashamed to speak of what you saw. The same boys and

girls are there, the same old grandmothers. But clear eyes look up, and

there is no look of shame anywhere. It is hard to speak of such things, but

you alone are ashamed that day; and when you are gone, the same horror is

practised under the same clear moon.

“No; I cannot yet speak of the bitterness of heathenism, only

of its horror. True, there were hags there who were only middle-aged women,

and there were men bowed, scared, dull-eyed, with furrowed faces. But when

these speak or sing or dance, there seems to be no alloy in their merriment.

The children are happy as only children can be. They laugh and sing, and

show bright eyes and shining teeth all day long. But what of that? Made in

God’s image, to be His pure dwelling-place, they have become the dens of

foul devils; made to be sons of God, they have become the devotees of

passion.

“I have passed through the valleys of two little rivers only,

and seen there something of the external life of those who can be the

children of God. The horror of it is with me day and night. And on every

side it is the same. In hidden valleys where we have never been, in villages

quite near to this station, the drum is beating and proclaiming shame under

God's face. And we cannot rest. But what are we two among so many? 0 men and

women, who have sisters and mothers and little brothers whose daily presence

is for you an echo of the purity of God, why do you leave us a little

company, and grudge those gifts that help to tell mothers and daughters and

sons that impurity is for hell, and holiness alone for us!

“How long, 0 Lord! how long?"

“I send you this account of a missionary journey. Would that

my pen could write the fire that is in my soul! It is an awful thing to sit

looking at sin triumphant, and be unable to do anything to check it. Calls

for teachers are coming from every side, but we cannot listen to them at

present—our hands are more than full.”

The letter refers to the custom as it obtained among the

Tumbuka and Tonga slaves, and it presents an awful picture of moral

degeneracy which was all too commonly seen on such occasions all over

Central Africa. Although the Ngoni practice was less openly obscene yet the

occasion was onž of unspeakable evil, extending over several days, on which

both sexes were accorded full licence for every unholy passion.

In like manner in connection with marriages —especially of

widows—and the birth of twins ; when armies returned from war and the

purification ceremonies took place, practices which are not meet to be

described were unblushingly engaged in. What in Christian lands is held

sacred in heathen lands is too often the common property of young and old,

and where public opinion is devoid of the moral sense we cannot look for

elevation from within.

One of the greatest social and moral evils among the tribe is

polygamy. The evils are seen among all classes, for as the tribe existed by

raiding other tribes, all who could bear arms might possess themselves of

captive wives. Among the upper classes the rich held the power to secure all

the marriageable girls in the tribe, by purchasing them from their parents

for so many cattle. The practice of paying cattle was not in all cases

wholly bad, but the tendency was to outrage the higher motives and feelings,

especially in the women who often were bargained for by tbeir parents long

before they entered their teens. The cattle paid to the father of the bride

formed a portion which she could claim and have as a possession, in the

event of her being driven away by the cruelty of her husband, and, in the

absence of a nobler sentiment, it was in some degree a safeguard of the

interests of the wife. But upon no grounds, social or moral, could such a

practice be defended. It is inimical to the true morality of marriage, and

consequently to the progress of the race. It is no uncommon thing to find

greyheaded old men, with half-a-score of wives already, choosing, bidding

for, and securing, without the woman’s consent, the young girls of the

tribe. Disparity of age, emotions and associations, make such unions

anything but happy, and nowhere do quarrels and witchcraft practices foment

more surely than in a polygamous household. A man’s wives are not all

located in one village. He may have several villages, and from neglect young

wives are subject to many grievances and temptations, so that it is no

wonder they age in appearance so rapidly. They are often maltreated by the

senior wives, who, jealous of them, bring charges against them, and, in the

hour when they should have the joy of expectant motherhood, they are cast

aside under some foul charge, without human aid or sympathetic care. On more

than one occasion I have been called by a weeping mother to give aid to her

daughter in such circumstances, when, if a fatal issue resulted, she and her

family would have been taken into slavery and their possessions confiscated.

Only those who spend years among them and are their trusted friends can tell

of that and countless other unholy and inhuman things, which result from the

custom of polygamy as it exists.

Flippant writers on such customs, especially some travellers

who had not the opportunity of becoming acquainted with the people, state

that polygamy is, in the savage state where there is an absence of higher

motives, a safeguard of morality. It is, however, far from being so. Men

with several wives, and many of the wives of polygamists, have assignations

with members of other families. I have been told by serious old men that

such is the state of family life in the villages that any man could raise a

case against his neighbour at any time, and that is one reason why

friendliness appears so marked among them—each has to bow to the other in

fear of offending him and leading to revelations which would rob him of his

all.

The belief in witchcraft is the most powerful of all the

forces at work among the tribes. It is a slavery from which there has been

found no release. It pervades and influences every human relationship, and

acts as a complete barrier to all advancement wherever it is found to

operate. No matter whether it be master or slave, chief or subject, parent

or child, he has to bear this yoke which may at any moment crush him. He

lives in fear. If he is sick it is not a question of how he may be cured,

but of who has bewitched him ; or if his plans are frustrated what evil

spirit has been moved against him. The reason for his apparent laziness is

the feai that, if he become possessed of goods, his circumstances will

excite jealousy and bring on him accusations of witchcraft, and death as a

result. It is productive of unrest, cruel treatment, and great loss of

property and life.

The itshanusi or witch-doctor lives upon the credulity and

slavish fear of the people. He is either self-deceived or a base impostor,

but his power for evil in a tribe is unlimited. He is reverenced by all

classes, and although one may hear whispers of a want of faith in him and

his incantations, no one would dare to oppose him in public. Wicked men and

chiefs make use of him and his immunity from punishment to “remove” any

person who is disliked or whose possessions have rendered him opprobrious to

them, and a chief or headman’s unjust demands may be bolstered up by an

appeal to his easily-bought action. They aid despotic chiefs in governing a

discontented people, and from the deep religious feeling which the people

have in regard to the presence and power of the ancestral spirits with whom

the itshanusi is believed to be in communication, they are ready to

acknowledge even that which may be to their hurt.

As to their belief in witchcraft I might refer to what I have

observed in the course of my practice of medicine among the people. No

sooner is it concluded that a person who is sick has been bewitched, than

the friends around talk of it without constraint in the presence of the

patient. Sometimes they may carry him about from place to place in the hope

of cheating the charmer, but the effect on the patient is very marked. He

seems to conclude that he is to die, and he evinces no fear or anxiety in

view of death. He assumes an unnatural stolidity, despair, and what might be

termed resignation. Although his imminent death is talked of freely before

him he has no fear or complaint. He shows no desire to fight for life, but

with an inhuman want of hope or desire for recovery he awaits the end. The

thought that he is bewitched seems to deprive him of all natural clinging to

life. Even among the youthful of both sexes there is that want of hope, when

once the elder people have declared they have been bewitched.

In connection with charges of witchcraft, the poison ordeal

is the final and too often calamitous sequel. Before the light of Christian

truth came to them, and has, even where the doctrines are not wholly

embraced, done away with this great evil, the number annually killed by

drinking the muave cup cannot be estimated. Anything a man possesses, about

which there is any mystery, may give rise to a charge of witchcraft. If a

man is found walking near a village at night he is charged with evil

intentions. If one possesses himself of an owl or other night bird or

animal, he is supposed to work evil by means of such, and is charged

forthwith. When sickness or death comes into a house or village someone is

blamed. Theitshanusi is called, and there are not wanting those who in their

talk reveal in what direction the thoughts of the people lie, and so he

names someone, which decision at once appears reasonable to the people and

is accepted. Often the witch-doctor has emissaries secretly employed to find

out what he wants, and, acting upon information thus obtained, he appears to

the people to be acting upon communications he has received supernaturally.

Sometimes he does more to influence their imagination and make themselves

name someone than by himself doing so directly. I have known several

witch-doctors, and have come to regard them as shrewd individuals, certainly

more given to thought than the community generally, and who traded on the

superstitious fears of the people, who seldom exercised their reason in

connection with ordinary occurrences. On many occasions men and women have

sought refuge at the Mission station when accused of witchcraft and under

sentence of death. On one occasion, during a trial which took place at a

village near the station, when the itshanusiwas performing his incantations

and condemned a man, he broke away from the crowd and ran towards the house.

He was followed by a crowd of men and boys clamouring for his life, and

being overtaken, was clubbed to death before our eyes; his body was

ignominiously dragged back to the scene of trial, where it was subjected to

gross indignities.

On all occasions of administering the poison cup we tried to

stop it. Sometimes we were successful and sometimes we were not. Sometimes

we were able to prevail upon them to substitute dogs or fowls for the human

subjects, and then it was possible for us to watch the proceedings. These

were occasions on which the whole community turned out. The friends of the

accused were very few on such occasions, and the people jeered the unhappy

wretch and engaged in song and dance while he had to stand alone and prove

his innocence by vomiting the poison, or, by death from the poison, confirm

the truth of the charge against him. When the poison began to take effect,

as seen in the quivering and collapse of the culprit, it was the occasion

for wild demoniacal behaviour, jeering and cursing the dying man, unawed in

the presence of death. Then his body was ignominiously cast into the nearest

ravine to be food for the hyenas at night.

Not only was the poison ordeal resorted to in cases of

supposed witchcraft, but the Tonga and Tumbuka, with whom and not with the

Ngoni the practice originated, were incessantly using it. In nearly every

hut a bundle of poison-bark would be found hid away in the roof against the

need to use it. Family and other quarrels were finally adjusted by resort to

the ordeal. The women were the mainstay of the horrible practice, and most

frequently made use of it. Numberless cases were treated at the dispensary,

when more sober reflection made them seek an emetic. Sometimes cases were

brought by others.

A husband might come home and find a crowd about his door and

learn that his wife had taken muave. He would bring her to me at once.

Sometimes the patient has died while being brought, or even at the

dispensary door while 1 was making an effort to save her. Frivolous as were

the reasons for resorting to such extreme measures when quarrels arose,

there were often dire results therefrom, and sometimes one met with a case

which appeared ridiculous even to the native mind. A strong young man came

to me one day saying he had drunk muave, and desired an emetic. On enquiry I

learned that he and his wife had quarrelled during the night in the secrecy

of their own hut. Failing to agree after the usual amount of talking

characteristic of native brawls, they agreed that at sunrise they would

drink muave. When the sun rose they proceeded to the ordeal and the cups

were duly mixed. The wife, with a cunning not suspected by the pliable

husband, who, with a faith in his innocence, was determined to go through

with the business, said, “You made the charge, so you shall drink first.” He

did so, but the wife, hurling an imprecation at him, refused to drink her

share, and fled to a village several miles away. The poor man, amid a crowd

of natives derisively cheering him, came and sought relief, which a liberal

use of sulphate of zinc and water gave him.

The poison ordeal is an outcome of their belief in the

supernatural. It is an appeal to a power outside themselves to judge the

case, reveal the right, and punish the wrong-doer. It is part of their

religious system and appears to them to be right. The witch-doctor is to

them the visible and accessible agent of the ancestral spirits whom they

believe in and worship, and from whom they think he derives his powers. If

there is a tendency to error in what they believe, the witchdoctor by his

shrewdness and making bad use of it, pretending to know more than what will

ever be revealed to man, favoured the growth of lies, and juggled with the

truth of things. The characteristics of the witch-doctor are a pretended

superior knowledge to discern the affairs of individuals and communities,

and ability to hold intercourse with the ancestral spirits. It is not a

hereditary craft such as that of other kinds of doctors, e.g. medicine men

who have a knowledge of herbs, and blacksmiths who have the secrets of

working in iron. The knowledge of medicine and handicraft are considered to

be heirlooms. The witch-doctor is supposed to be chosen by the ancestral

spirits, by whom they may communicate with the world. A man who is chosen

presents certain features or symptoms. He becomes “possessed” and excludes

himself from society. He may have a peculiar sickness, characterised by

lowness of spirits. It may be he is the subject of fits or has peculiar

dreams. When he recovers from this and again enters society he is looked

upon with awe by the ordinary people. He places himself in the hands of some

old witchdoctor who tests his symptoms of “possession,” and if found good he

is instructed by him in various practices. He is not allowed to graduate,

however, until he has discovered some medicine which is potent in some way,

and given public proof of his ability to discover things secreted by those

assembled to test his powers. There is doubtless a measure of both

self-deception and imposture in the matter. The practice of the witch-doctor

is closely connected with the worship of the ancestral spirits. Each house

has a family spirit to whom they sacrifice, but no one ever sacrifices to

the spirit without first waiting upon the itshanusi. He pretends to have

found out the reason for worship, and directs the applicant how to proceed.

Without asserting that it is complete, the following is a

correct statement of the religious beliefs of the natives. Although they do

not worship God, it is nevertheless true that they have a distinct idea of a

supreme Being. The Ngoni call him Umkurumqango, and the Tonga and Tumbuka

call him Chiuta. It may be that the natives, from an excess of reverence as

much as from negligence, have ceased to offer him direct worship. They

affirm that God lives: that it is He who created all things, and who giveth

all good things. The government of the world is deputed to the spirits and

among these the malevolent spirits alone require to be appeased, while the

guardian spirits require to be entreated for protection by means of

sacrifices. I once had a long conversation on this subject with a

witchdoctor who was a neighbour for some years, and the sum of what he said

was, that they believe in God who made them and all things, but they do not

know how to worship Him. He is thought of as a great chief and is living,

but as He has the ancestral spirits with Him they are His cimaduna(headmen).

The reason why they pray to the amadhlozi (spirits) is that these, having

lived on earth, understand their position and wants, and can manage their

case with God. When they are well and have plenty, no worship is required,

and in adversity and sickness they pray to them. The sacrifices are offered

to appease the spirits when trouble comes, or, as when building a new

village, to gain their protection.

With such ideas native to the mind of these tribes, how is it

that the materialistic writers and unbelieving critics of Missions affirm

that the high moral and spiritual truths of Christianity cannot be grasped

by them? In beginning mission work among them, one is not met by anything in

their mental or spiritual life which is an insurmountable barrier in

communicating to them spiritual truths. However erroneously at first they

may conceive the truths and facts put before them, they have no difficulty

in finding a place for them in their thoughts. To talk of spiritual things

is not to them an absurdity, much less is it impossible for them to conceive

that such things may be. The native lives continually in an atmosphere of

spiritual things. Almost all his customs are connected with a belief in a

world of spirits. He is, consciously or unconsciously, always under the

power and influence of a spiritual world. In preaching, we have not first to

prove the existence of God. He never dreams of questioning that. We have in

our instruction merely to unfold His character as Creator, Preserver,

Governor, and Father of us all. As He is revealed to them they do not

question His sovereignty, but bow to it. While we meet with many obstacles

in their life and thought, yet as they are we have in them much that is a

help—a basis on which we may operate. However dim their spiritual light may

be, we have but to unfold truth to them and it is self-evident to their

minds. No preparation by civilization is required, as their spiritual

instincts find in the truth of God what they are crying out for. The cry is

inarticulate and unuttered, save in their unrest and blind gropings after

spiritual things.

Regarding the origin of life and death, all natives have the

story much the same as found throughout the Bantu tribes, how that in the

beginning God sent the chameleon to tell men that they would die but again

rise. Afterwards He sent the grey lizard to say that they would die, and

dying, would not return. The lizard, being a swift runner, came first, and

afterwards the chameleon; but men said, “We accepted the word of the first,

and cannot receive yours.” The natives hate the chameleon, and put snuff in

its mouth to kill it, because they say it delayed and led to their

acceptance of death.

They believe in the presence of disembodied spirits, good and

bad, having the power to affect men in this world. Their sacrifices to them,

their fear of them, and their assigning sickness and death to their agency,

testify to this.

There are different terms applied to spirits, each of which

is explanatory. The native thinks of the shade or shadow of his departed

friend, and denotes the life-principle, and the term is even applied to

influence, prestige, importance. They use it in reference to his life, as

when they say, “His shadow is still present”; meaning that though on the

point of death, his spirit is still in him. When I began to take

photographs, the same word was applied to a man’s photograph, and they

evinced the greatest fear lest by yielding up their spirit to me they should

die. I have shown photographs of deceased persons known to them, and they

invariably turned away, some even running away in fear. When a native

dreams, he believes he has held converse with the shade of his friend.

Another term applied to spirits has reference to their supposed habit of

wandering about. The hut of a deceased adult is never pulled down. It is

never again used by the living, but is left to fall to pieces when the

village removes to another locality. They do not think the spirit always

lives in the hut, but they think it may return to its former haunts, and so

the hut is left standing. Spirits are thought to enter certain snakes, which

consequently are never killed. When seen in the vicinity of houses, they are

left unmolested ; and if they enter huts, sometimes food and beer are laid

down for them. Some time after a chief died, some of his children saw a

snake near his grave close by the hut in which he died. The cry of joy was

taken up by all the family, “Our father has come back.” There was great

rejoicing, and the family went and spent a night at the grave, clearing away

the grass and rubbish that had accumulated. They were satisfied that it was

the spirit of their father in the snake.

If a journey of importance is being taken, such as an army

going out to war, or a man going on important business, a snake crossing the

path in front is considered to be an omen—the spirit giving warning against

going on. The army or party interested would not dream of going farther,

without consulting the divining-doctor so as to learn the meaning of the

omen.

Their belief in spirits appears on many occasions. I have

been engaging workers when only a few out of a crowd could be chosen. It was

not an uncommon thing to hear from the disappointed as they walked away, “I

have an evil spirit to-day,” meaning that luck went against them, and they

were not engaged. A man who has perhaps narrowly escaped from danger

exclaims, “What did they take me for?” meaning that some inferior spirit had

been caring for him, and only barely saved him. Such a definite and

operative belief in the presence and power of spirits gives rise to their

practice of offering sacrifices, which are almost always propitiatory, save

when a new village is made. Hence their religious exercises are called forth

by sickness, death, or disaster. A man speaks of a sacrifice as offered to

make the spirit pliable and obedient to his request, and in sacrifice they

offer cattle, or beer and flour.

Although the Tumbuka are a much more degraded people in

morals, they are more religious than the Ngoni, and are freer in their

sacrifices. An elephant-hunter, for example, when the beast falls, always

cuts out certain parts, and at the foot of a certain tree offers them in

sacrifice to his guardian spirit. Their beliefs and worship are essentially

those of the Ngoni, except that they have a wider variety of objects.

Certain hills are worshipped, also waterfalls, ancient trees, and almost any

object which appears unusual, may to them embody the spirit they worship,

while certain insects, such as the mantis religiosa are supposed to give

residence to an ancestral spirit, are not interfered with under any

circumstances, or even handled. Each house has its own guardian spirit, and

the tribe worships the spirit of a dead chief.

The natives believe in Hades — the region below, where

disembodied spirits dwell. They do not speak of it as a sensible locality.

Now and again women are found wandering about the country smeared with white

clay and fantastically dressed, calling themselves “chiefs of Hades.'’ They

are greatly feared as being able to turn themselves into lions, and other

ravenous beasts to devour any who may not treat them well. Hence their

advent in a village leads the people to give them whatever they ask, that

they may go away and leave them undisturbed. There is a medicine in use as a

protection from lions, which cunning men sell at a good price. One of the

largest and most attentive meetings I had in the open air was when, on a

Sunday morning, I came upon a crowd of natives of both sexes and all ages,

submitting to be anointed by a deceptive old man with an oily mixture, which

was reputed to give protection from the lions at that time infesting the

district. At my request he ceased his practice and I preached from the

words: “The devil goeth about as a roaring lion seeking whom he may devour.”

Before the close of the sermon the old man took his departure with his oily

mixture, leaving me in possession of the crowd.

Much more might be said of the life of the people, but what

has been stated will enable the reader to understand the nature of the soil

into which the seeds of Christian truth have been cast, and how great have

been the results. Frederic Harrison’s New Year Address to the Positivist

Society ten years ago contained these great swelling words of man’s

wisdom:—“Missionaries and philanthropists, however noble might be the

character and purpose of some few among them, were all really engaged . . .

in plundering and enslaving Africa, in crushing, demoralising and degrading

African races.” I have but faintly touched upon the moral and spiritual, as

well as the temporal state of the natives as we found them; let the reader,

when he has gone through the succeeding chapters, say for himself whether

the plan of God’s redemption of Africa or that of the Positivist Society

succeeds best, and take no rest until all Africa receive the light of God’s

Word. |