|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

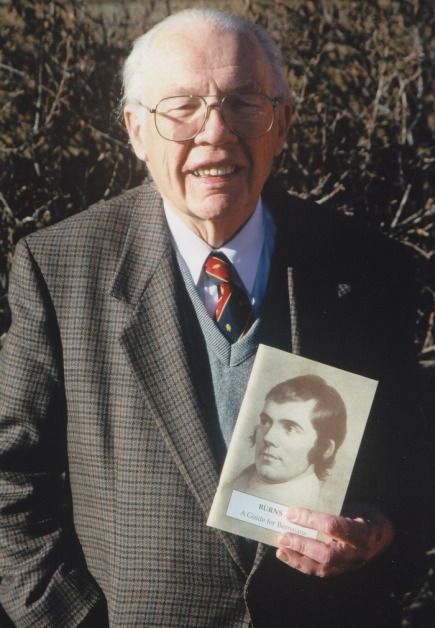

This is the last speech I have at this time from the

files of the late Dr. Robert Carnie. His son Andrew has been quite gracious

in allowing me to share the work of his father with our readers. Just who is

Robert Carnie? This Dundee Scot is a graduate of the

University

of St. Andrews

and earned a PhD in English literature. His life was spent teaching at

various colleges in

England

and Scotland

and then for 20 years at the University

of Calgary

in

Canada.

Bob was also an author, and his inspiring and wonderful book,

Burns

Illustrated, published by the Calgary

Burns Club, was reviewed October 30, 2008 on my website

A Highlander

and His Books and can be found at

http://www.electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns_illustrated.htm.

Like most of us who speak and write about Robert

Burns, Dr. Carnie was an avid collector of signed decorative books on Burns.

In 2006 this wonderful book collection was donated to the

University

of Calgary.

Dr. Patrick Scott, Director of Special Collections, Thomas Cooper Library,

and Professor of English at the

University

of South Carolina,

said in the

Significant

Scots section on

www.electricscotland.com

that “Bob was the bard, distinguished life member and past president of the

Calgary Burns Club and a life member and frequent speaker at the

Schiehallion Scottish Society.” To read more about the remarkable Dr.

Carnie, please refer to

http://www.electricscotland.com/other/carnie_robert.htm.

(FRS: 7.22.09)

Burns the Improviser

By

Robert H. Carnie

A pamphlet

Robert H. Carnie

published in 2000 (called Burns 200, a guide for Burnsians), published by

the Schiehallion Scottish Club in Calgary

At this time of year - The Burns Supper season - I am

always looking for something fresh and different to say about my favourite

Scottish poet.

Among home-grown Scots, expatriate Scots, and

the poet's countless admirers in the rest of the world, there is a good deal

of unanimity about their favourite parts of Burns's poetic output.

Amongst his narrative pieces, most people like

or love 'Tam 0' Shanter, the 'Cotter's Saturday Night' ,' Holy Willie's

Prayer,' and 'The Twa Dogs',

and

I don't think I've ever met a lover of Burns

who did not relish

his countless

memorable songs -'Auld Lang Syne', 'Ae fond

Kiss,' (which was one of the three pieces I read to you last year) 'Corn

Rigs',

'Scots wha hae' and dozens of others that spring to

mind.

But Burns had another talent that is not so often

celebrated, and that is his ability, to compose, 'off the cuff' and

apparently without much previous thought, little snatches of verse - two,

four , eight or 16 lines - which commemorate, celebrate, or excoriate some

event or experience in his own life.

Burns was indeed a ‘natural poet' who wrote

verse spontaneously. He disconcerts 20th

century academic critics by refusing to take his poetic art too seriously.

In the poem 'The Vision' he refers, almost

contemptuously, to his song writing activities as 'Stringing blethers up in

rhyme/ for fools to sing.' As he puts it in one of his less well known

poetic epistles:

Some

rhyme a neebor's name to lash;

Some rhyme (vain thought!) for needfu' cash;

Some rhyme to court the countra clash.

And raise a din;

For me, an aim I never fash;

I rhyme for

fun.

As my former colleague at St. Andrew's University,

Donald Low, says in his collection of critical essays about Burns (I quote):

'Burns is an improviser of genius. Improvisation in art proves disconcerting

to people accustomed to impose a tidy conceptual framework on what they

study'.

But tonight I don’t want to philosophise about the

differences between improvised art and schematic or planned art, and I am

equally sure none of you want to hear me blether on that subject!

Instead, I would like to recite to you a few

examples from the hundreds of

short poems - epigrams, epitaphs,

bon-mots,

and occasional poems, to demonstrate how skilled Rabbie Burns was at writing

short pieces 'off the cuff'. The first one is a note of thanks. When

the new house at

Burns's farm, Ellisland, was being built,

the poet had no place to go away from his

family, and

Captain

Riddell at Friar's Carse gave the poet a key so

that he could go, any time he liked, to think and write in a little

hermitage, or summer house, in the grounds of the estate. This is Rabbie’s

reply to an invitation to dine from Captain Riddell:

Dear

Sir, at onie time or tide,

I'd rather sit wi' you than ride;

Tho' t'were wi' Royal Geordie:

And truth your kindness soon and late

Aft gars me to mysel look blate -

The Lord in Heaven reward ye!

Few patrons of a poet can have received a more

affectionate and sincere letter of thanks.

It is a great pity that a drunken party at the

Friar's Carse mansion house, some time later, should have so marred Burns's

friendship with the Riddell family. Another forgotten slip of happy verse

that Burns wrote in this part of the world are the lines:

Envy,

if thy jaundiced eye,

Through this window chance to spy,

To thy

sorrow thou shalt

find,

All

that's generous, all that's kind,

Friendship, virtue, every grace,

Dwelling in this happy place.

Burns wrote these lines with his diamond ring on a

window at the Queensberry Arms at Sanquhar. Burns often called there while

travelling between Mauchline and his farm at Ellisland.

He clearly believed in praising human goodness.

Burns was a keen observer of the houses of the great and rich that he

visited, and once, when he was in the library of a Scottish nobleman, he was

shown a splendidly bound early edition of Shakespeare's

Works,

where the text was severely damaged by insect pests. He jotted down the

following four sarcastic lines about distorted values:

Through and through the inspired leaves,

Ye maggots, make your windings;

But 0, respect his lordship's taste,

And

spare the golden bindings!

Another of my favourite short satiric pieces that

Burns dashed off about the high and mighty of this world is the one called

'The keekin' glass', i.e. 'the looking glass'. He tells the story of an

ancient and learned Scottish

judge who had got so drunk the night before

that, coming into the drawing-room at Dalswinton Inn, he pointed at the

landlady's daughter and asked her father 'Wha's yon howlet-faced thing in

the corner?'

The young lady, Miss Miller, was much upset at

being called 'howlet-faced' (owl-faced)so, to cheer her up, Burns, who was

also staying at the inn, wrote the following four lines, and gave them to

her:

How

daur ye ca' me 'Howlet-face',

Ye blear eyed withered spectre?

Ye only spied the keekin' glass,

An' there ye saw

your

picture!

Burns was not fond of civil servants either. He

particularly disliked a man called Thomas Goldie, a commissary of the

sherriff-court in

Dumfries and the President of a

right wing political club called 'The Loyal Natives' whose political views

were anathema to a democrat like Burns. So he wrote this quatrain about

Thomas Goldie's lack of brains and the thickness of his skull!

Lord,

to account who does Thee call,

Or e'er dispute Thy pleasure?

Else why within so thick a wall

Enclose so poor a treasure?

The next mock-epitaph, out of the scores that Burns

wrote, that I'd like to quote to you is the one that he wrote on James

Humphrey, stone-mason in Mauchline, a man famous locally for his fondness

for argument and debate, and for his ability to

lose

all the debates in which he took part. Jamie Humphrey lived for 48 years

after Burns, and he loved to recall his losing debates with the poet. Burns

wrote in the 1780's this famous 'phony' epitaph on him:

Below

these stanes lie Jamie's banes:

O Death, it's my opinion,

Thou never took such a blethrin' bitch

Into thy dark dominion.

On his travels throughout Scotland,

Burns wrote a great many of the 'off-the-cuff' little poems which were

collected and added to his complete

Works

after his death. When Burns was on his Border tour in 1787, he spent some

time with the family of his friend Robert Ainslie, at the family farm at

Berrywell in Berwickshire. As he tells us in his

Journal,

he went with the family to church in the town of Duns

on Sunday.

He was seated next to the unmarried daughter,

Miss Rachel Ainslie. When Burns saw her looking in vain in her Bible for the

text given out by the fiery preacher on his theme 'The Impenitent Sinner',

he offered to find the passage for her, but instead he wrote the following

lines in the fly-leaves of her Holy Book:

Fair maid,

you

need not take the hint,

Nor

idle texts pursue;

'Twas guily sinners that he meant,

Not angels such as you!

It will be no surprise to most of you that Burn's

Journal

records that Miss Ainslie was an attractive young lady: 'Her person was a

little

embonpoint but handsome; her face,

particularly her eyes, full of sweetness and good humour; she unites three

qualities rarely to be found together: keen solid observation; sly, witty

remarks; and the gentlest, most unaffected female modesty.'

I think Rabbie was paying more attention that

day to the bonnie lassie sitting next to him, than to the preacher's sermon!

Burns

also greatly enjoyed his visit to the Highlands of Scotland in September,

1787. When he and his friend and fellow traveler William Nicol went up

Glengarry to Dalwhinnie, he recorded the following four lines:

When

death's dark stream I ferry o'er'

(A time that assuredly will come)

In Heaven itself I'll ask no more,

Than just a

Highland

welcome.

Finally, one of my personal favourites among the mock

epitaphs- an eight line poem entitled 'On a wag in Mauchline'. It is about

James Smith, a close friend of the poet. Smith was brought up very strictly

by his stepfather, but he rebelled, and along with Rabbie and a man called

John Richmond, Smith was regarded as one of the 'wild lads' of the local

district. The third member of the triumvirate, John Richmond, got his girl

friend Jenny

Surgeoner, (who was later his wife), pregnant,

and had to do public penance. James Smith, after failing in a variety of

jobs in Scotland,

went, as Burns himself almost did, to Jamaica,

and died there before 1808.

Burns wrote the following lines about Smith:

Lament him, Mauchline husbands a',

He aften did assist ye;

For had ye staid hale weeks awa',

Your wives they ne'er had missed ye!

Ye

Mauchline bairns, as on ye pass

To school in bands thegither,

O

tread ye lightly on his grass --

Perhaps he was your faither.

I

hope the little taste I've given you tonight of Burns's improvised verse

will encourage you to read some of the poetry of Burns outside the well

established favourites. Thank you for your attention.

RHC

14 January, 2000.

|