|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

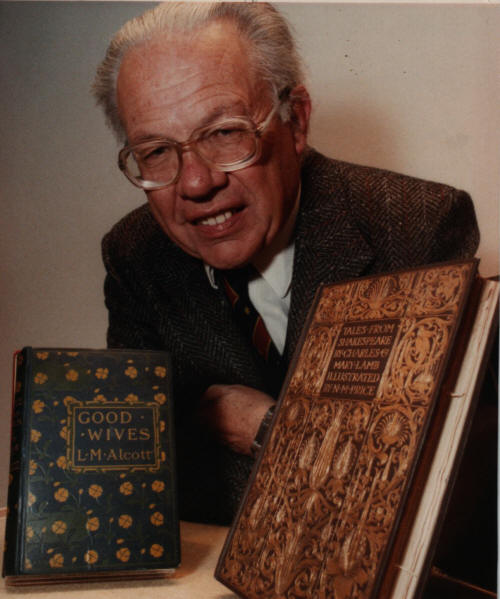

Robert H. Carnie with his Books

The

following questions come from an email interview with Andrew Carnie, son of

the late Robert H. Carnie, in December, 2008. Robert Carnie was a Burns

scholar and a fellow Burnsian who would be at home at any academic symposium

or in a typical gathering of ordinary men and women who would meet to honor

Scotland’s

National Bard. Andrew has worked closely with me in providing speeches by

his father. As these speeches are read, one will come to the conclusion his

speeches did not die the death of so many others which have been filed,

locked away, or forgotten after the passing of one who actually had

something to say about Robert Burns. By sharing these speeches, Andrew made

it possible for his father’s work to live on and be enjoyed by those who

read these pages. I tip my hat to Andrew and thank him for his cooperation

in giving permission for these speeches to go on this website where his

father’s scholarship and love of Robert Burns will continue to live and be

enjoyed by all of us. After all, it was Mary, Queen of Scots who embroidered

these words before her death:

“En ma Fin git mon

Commencement…”

“In my End is my Beginning…”

Interview conclusion:

FRS:

Are there other papers, articles or speeches your father prepared on Burns

and would you be willing to share any of them with our readers?

AC: He wrote a lot, much

of it was published in the professional literature. We do have many of his

unpublished talks and speeches but it is all in hard copy -- and I don't

have access to it here.

FRS: Did he ever talk about his experiences the summer

he studied at the University

of South Carolina?

If

so, how did that time in

Columbia

influence him regarding Burns? He is remembered at the University with great

fondness by Drs. Patrick Scott, and Ross Roy. Both speak very highly of him.

AC: While he was there

he made use of Dr. Roy's collection for developing his own research. In

particular he was pleased to see and hold items of the collection in person.

He thoroughly enjoyed the great opportunity to collaborate and interact with

colleagues like Drs. Roy and Scott who shared his passion for the material

FRS: Was your dad working on anything related to Burns at his untimely

death? If so, will you share it with our readers?

AC:

My dad had many great plans for a new book on

18th century book designers, including many who worked on Burns volumes.

Unfortunately a series of strokes in 2000 prevented him from completing this

work. Although he occasionally went back to it, his long illness from

2000-2007 meant that he wasn't really able to complete it.

FRS: What sort of library did your dad have on Burns?

How large was it and what happened to it? Same for his Scottish library as a

whole.

AC:

Dad had two or three thousand antiquarian books

in our house. Most were Scottish. I'm guessing about 10-15% Burns. The

entire collection was donated to the University

of Calgary Library

in 2006.

FRS: This is an attempt on my part to continue to honor your dad and nothing

else. Can you describe the two pictures you sent to Jim Osborne and me?

AC:

The studio picture dates from 1993 when The Calgary Burns Club hosted the

Federation's annual general meeting.

They

along with the Rare Book's library put on an exhibition of decorated covers.

The other picture is of Dad standing in our back yard. A very typical pose

for Dad, he often read like that in Garden, from the late 1990s.

FRS: I notice you have an arizona.edu email address. How are you affiliated

with that educational system?

AC: Yes, I'm a professor

of Linguistics here.

FRS: Many thanks for your time and for the pictures.

AC: My pleasure, thanks

again for thinking of my Dad and his work.

(FRS: 7.15.09)

Robert H. Carnie in his garden

Robert Burns -

Writer of Songs

By Robert H. Carnie

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I

was reading the other day one of these manuals about successful public

speaking, and I began to wonder how I had managed, in my long career as a

teacher, without one of these handy guides! One of the first pieces of

advice in it was to begin with a joke or a humorous story to relax (and I

quote) "both my personal tension, and that of my audience".

I must confess it is a number of years since I

began any kind of public presentation in this way. I suppose that has

something to do with my age, and the unreliability of my short-term memory,

for believe me - if I start telling a joke, and cannot remember the

punch

line,

it may give my audience a giggle but it does very little for my personal

relaxation! Nevertheless I am going to start tonight with a joke, one that

came to my mind when I was listening to Bill Shank's splendid 'Address to a

Haggis' at our recent Burns Supper.

When Bill came to the lines:

But mark the Rustic

haggis-fed,

The trembling

earth resounds

his tread.

he

affectionately poked the stomachs of his two splendid sword-bearers. A

much less affectionate joke was played by George

Bernard Shaw on his fellow club member, G. K. Chesterton, in their club

lounge, when he went up to his overweight fellow writer, poked him in the

stomach, and loudly said: "What are you going to call it when it arrives,

Chesterton?" Chesterton's answer was a classic retort. He said "That is an

easy question to answer. If it is a girl, I will call it Elizabeth,

after my mother. If it is a boy, I'll call it Gilbert after my father, but

if it is what I fear it is:

'A big bag of hot air and wind' I'll call it

George Bernard Shaw!

Well there it is - my obligatory opening joke. A much more difficult task,

given the fact that Burns wrote the words and selected the music for

hundreds of Scottish songs was to pick 6 or 7 out of the complete corpus

that I think are both typical of his work as a lyricist, and which

demonstrate his immense genius at this kind of literary activity. Neither

the Kilmarnock edition of 1786 nor the Edinburgh

edition of 1787 contained many songs alongside the splendid narrative tales,

epistles and satires that constitute the main body of these editions. In

fact of the four songs that close the

Kilmarnock

edition, and seem suspiciously like an afterthought, only one,

Corn Rigs,

has become a perennial favourite. Let me remind you of the first stanza:

It was upon a Lammas

night,

When corn rigs are bonnie,

Beneath the moon's unclouded light;

I held awa tae Annie;

The time flew by wi' tentless heed,

Till 'tween the late and early;

W'i' sma' persuasion she agreed,

To see me through the barley.

Chorus

Corn rigs, an' barley rigs,

An' corn rigs are bonnie;

I'll ne'er forget that happy night,

Amang the rigs wi' Annie.

It

is perhaps worth noting here that the chorus is a cleaned up version of the

original chorus in Allan Ramsay's

Gentle Shepherd,

and that the tune is also to be found there.

Only seven more songs were included in the

Edinburgh edition of 1787, including Burns's version of the old song 'John

Barleycorn' (that is the one we have great fun making a mess of at our own

annual Burns Suppers), and 'Green grow the

rashes 0' which is a little masterpiece of wit, gaiety and movement. Burns

had written this song down in his

First

Commonplace Book in August 1786, and there

also varying versions of an original, and much sexier song,

that Rabbie collected for his private collection

of 'high kiltit' verse, a collection later published, after Burns's death,

as The

Merry Muses of Caledonia. I don't want to

offend anyone so I'll quote only the first stanza of the old song as given

in Herd's

Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs:

Green grow the rashes -

O

Green grow the rashes -

O

The feather bed is no sae saft

As a bed among the rashes O!

Burns's respectable version was also published in the first volume Johnson's

Musical

Museum, in May 1787. And the

mention of Johnson's name allows me to remind

you that it was Burns's stay in Edinburgh in 1787, and the interest he found

there in Scottish song, that encouraged him to turn away from non-lyrical

modes, like satire and narrative, and to devote a great deal of time to

improving, editing and writing Scottish songs. His two chief collaborators,

James Johnson, who lived from 1750 to 1811 and George Thomson, who lived

from 1757 to 1851, could hardly have been more different in personality and

interests.

Johnson is said to have been a native of

Ettrick, but when Burns knew him he was a music-seller and engraver in

Edinburgh.

He devised a process to strike

words, musical staves and notes on pewter, which

was supposed to cause a considerable saving in production costs, but neither

his invention or his publication, brought him wealth and he was nearly

penniless when he died 15 years after Burns, and his totally destitute widow

died in the Edinburgh workhouse in 1819. Burns took up Johnson's work as a

collector and publishers of Scottish song and from 1787 to his death in 1796

he was the real editor of the

Museum.

Included in Burns's enormous labours for this

publication were more than 200 songs of his own. Three more volumes of

Johnson's

Musical Museum

were published during the poet's lifetime.

The text for Volume 5 was ready for the

press just before the poet died. Volume 6, without the impetus of Burns's

knowledge and energy, did not appear until 1803. What can one say about

James Johnson? He was a simple, hard-working man, almost illiterate as his

few extant letters prove. But he was no fool. He soon recognised Burns's

superior knowledge and taste, and accepted without question all the

editorial advice that Burns gave him.

Johnson's work as a collector and publisher of

Scottish song was neglected, and sneered at by most of Burns's biographers

and later editors, but his great enthusiasm for Scottish music, had been

part of his personality some time prior to meeting Burns in the Spring of

1787.

The thin first volume of

The Scots

Musical Museum, containing 100 airs, was

almost ready for publication before the fortuitous meeting with Burns. It

contained only 2 of Burns's songs but the next four volumes were full of the

poet's genius as a writer and editor of Scottish song. What about the music?

Well most of it, but not all of it was traditional Scottish folk music.

Johnson' main musical advisor was one Stephen

Clarke (died 1797). When Rabbie first met Clarke in 1787, he was the

organist of the Episcopal Chapel in

Edinburgh,

and a teacher of music. It was Clarke, and later his son William for the

1903 volume, who harmonised the airs for Johnson' Scots

Musical

Museum.

Rabbie was not a great admirer of Stephen Clarke's work. In 1792 Burns wrote

him a very sarcastic letter criticising Clarke's failure to provide music

lessons to the children of friends of Burns.

Let me quote a little passage from this letter

telling the musician about the teaching job. Burn says that he is aware

"that Mr. Clarke may have his own terms, and be as happy as Indolence, the

Devil and the Gout will permit him.

Mr. Burns knows well that Mr. Clarke is engaged

so long with another family; but cannot Mr. Clarke find two or three weeks

to spare to each of them?

Mr. Burns is deeply impressed with, and awfully

conscious of, the high importance of Mr. Clarke's time, whether in the

winged moments of symphonious exhibition at the keys of Harmony, while

listening seraphs cease their own less delightful strains… Half a line

conveying half a meaning from Mr. Clarke would make Mr. Burns the very

happiest of mortals!

(July 16, 1792)

As

I've said above, Burns's other collaborator, George Thomson, was a different

kettle of fish from James Johnson.

He was the son of a schoolmaster and had trained

as a lawyer's clerk, and had become a junior clerk to the Board of Trustees

in

Edinburgh; and he

subsequently became the chief civil servant to that Board.

In

1792, Thomson took the lead among a group of musical amateurs in

Edinburgh

who were projecting

A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs.

This was intended to be in every way a much more

elegant work than Johnson's

Musical Museum.

In his correspondence with Burns, right from the

start, Thomson tried to lay down the law to his famous collaborator.

Thomson stressed two details: that there must be

no indelicacy in the songs in his collection, and that English words were

(in Thomson's opinion) preferable to Scottish words. Thomson was very

conventional-minded and he regarded himself as a keen judge of both poetry

and music, and he meddled constantly both with Burns' words and with the

tunes to which they were written.

For example, he tried very hard to change the

choice of tune for 'Scots wha hae', insisting on a tune called "Lewis

Gordon" as opposed to the tune to which the song is always sung, "Hey Tuttie

Taitie", and made suggestions about how the whole thing could be improved.

This Burns, I am glad to say, refused to do.

When Ludwig van Beethoven was recruited to

harmonize the airs for the

Select Collection, he

was requested by Thomson to make changes in his music, and Ludwig replied

angrily (in French), "I am not accustomed to re-touching my compositions: I

have never done it."

At Burns's early death, only the first number of

Thomson's

Select Collection had

appeared, but he went ahead, willfully altering or rejecting the songs which

the poet had sent already sent him, and in many cases simply disregarding

the poet's explicit instructions as to the airs to which the songs were to

be set.

He also took it upon himself to prepare a selection of

his correspondence with Burns for Currie's famous four volume famous first

collected edition of

The Works of Robert Burns.

Thomson even went so far as to go through the

manuscripts of Burns's letters in his possession, and score out a whole

series of passages which reflected unfavourably upon himself, or spoke well

of his major rival as an editor Scottish song -- James Johnson.

What can one say about George Thomson?

He was not an evil man, and working on the songs

for Thomson gave Burns a good deal of pleasure in the last years of his

life, but one cannot help contrasting poor Johnson, dying neglected in every

way, and Thomson's admiration of himself, and his arrogance in dealing with

Burns. (A footnote about the Thomson family: Charles Dickens' unhappy wife

Katherine Thomson Hogarth was the granddaughter of George Thomson).

But

let me now turn, at long last, to the six songs I have chosen as

representative of Burns's genius as a song-writer.

I have left out the dreary dirges that Burns

sometimes wrote but I have included examples of three kinds of songs in

which he excelled.

These are: songs about the love of a man and a

woman, songs about the joys of drinking and friendship, and songs about his

love for his native Scotland.

The

first is "A Rosebud by my early walk".

This song was first published in Peter Urbani's

A

Selection of Scots Songs in 1794, and later

by Johnson.

Burns's notes tell us that this song was

composed to celebrate a lady called Jenny Cruikshank, who was the only child

of his schoolmaster friend, William Cruikshank of the High School, Edinburgh.

The air or tune was written by David Sillar, who

was first of all a merchant, and then a schoolmaster in

Irvine, and he

is the same Davie

to whom Burns addressed his poem "The Epistle to

Davie".

This is one of Rabbie's songs written in the

English style, and it is a celebration of the pleasure that human beings

take in observing the joys of being young. The roses are rosebuds; the

linnet has chicks in her nest; and young Jenny, the heroine of the poem, is

another example of the vital beauty of young womanhood.

[Play song].

Auld Lang Syne.

Although there has been a good deal of controversy about how much of this

poem is traditional, and how much of it is Burns's original composition, it

seems to be the case that the only part of this extremely well-known poem

which we can

definitely say

pre-dates Burns, is the chorus:

For auld lang syne, my

dear,

For auld lang syne,

We'll tak a cup o' kindness yet

For auld lang syne

Burns told Thomson in a note that he took these words down from an old man's

singing, and there has been great argument about how much of the rest of the

song is also traditional. The air or tune had been known in print since

1700.

It is hard for me to say anything even vaguely original

about a song as well known as this one, which is now sung all over the

world. Burns does stress in his stanzas the importance for human beings to

remind themselves of old acquaintance.

He points out in stanzas 3 and 4 that the

friendships we make early in life with the children we played with, whether

it be picking daisies or paddling in the burn, always remain in our memories

even after long and permanent separation.

He also celebrates the ways in which human

beings confirm old friendship. They'll have a drink together; they'll shake

hands with their old friends, and reminisce kindly with them.

The song is, in my opinion a splendid piece of

poetry in which not a word is wasted by the poet.

[Play song]

Willie brewed a peck o' maut

As

far as I know, the whole of this song is original.

In the autumn of 1789, Robert Burns and Allan

Masterton, the writing master in Edinburgh

High School

and amateur musician, visited their mutual friend, William Nicol, also a

dominie, who was on holiday at the little town of Moffat.

They had such a good time that Masterton and

Burns decided they would celebrate the occasion by creating a song.

The result was this song, which can be properly

described as a

bacchanale - a true

celebration of the joys of a good booze-up.

Let me remind you of the chorus:

We are na fou, we're nae

that fou,

But just a drappie in oor e'e!

The cock may craw, the day may daw,

An' aye we'll taste the barley bree!

[Play song]

Ae

Fond Kiss

This song is a little unusual, in that Burns found the inspiration for it in

a song written in the early 18th

century by Robert Dodsley.

Dodsley's song began:

One fond kiss before we

part,

Drop a tear and bid adieu;

Tho' we sever, my fond heart

Till we meet shall pant for you.

It

goes without saying that Rabbie's version is much better.

Burns wrote this song (along with another nine

that are not nearly so good) to celebrate the end of his affair with

'Clarinda' (Mrs. Nancy Maclehose) who sailed from Greenock to the

West Indies in

1792.

It is one of the great songs of parting between a man

and a woman who are enormously attracted to one another.

I'll ne'er blame my

partial fancy

Nothing could

resist my Nancy

But to see her was to love her

Love but her and love forever

Had we never loved sae kindly

Had we never loved sae blindly

Never met and never parted

We had ne'er been broken-hearted.

[Play song].

Scots wha hae

Burns's best-known patriotic song is the one generally known as "Scots wha

hae”.

Burns sent the words of this song to the English

newspaper

The Morning Chronicle

in May 1794.

He preferred that it appear anonymously, but the

preface to the poem in the newspaper said there was but one living poet to

whom it could be ascribed. Burns composed the words of this song, and

insisted that they be sung to a traditional air, "Hey Tutti Taitie". He

wrote it while on an evening walk; it celebrates Robert Bruce's success at

the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Burns later sent a copy to his friend

John Syme in Dumfries.

It has been very fittingly called "Scotland's

unofficial national anthem".

It works equally effectively as a spoken ode and

as a stirring song.

[Play song].

A

man's a man for a' that

This very well-known song most perfectly expresses Burns's political

radicalism and his intense dislike of the vanities of rank and position, and

has been described as the Scottish

Marseillaise.

But it is a

Marseillaise

for all humanity.

As a political egalitarian myself, I

particularly enjoy the last lines:

For a' that and a'

that,

It's comin' yet for a' that,

That man to man the world o'er

Shall brithers be for a' that.

It

first appeared as a song in Thomson's

Select

Collection.

[Play song].

RHC Jan 2000

|