|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Megan with the replica of Burns skull presented

to Dr. Ross Roy

by Scotland's Colin Hunter McQueen.

I’ve met many wonderful people while editing Robert

Burns Lives! over the years, and today’s guest writer is no exception.

While attending the tremendous conference on Robert Burns At 250, An

International Conference of Contemporaries, Contexts, & Cultural Forms

held at the University of South Carolina in April, I was privileged to meet

three young ladies, all working on doctoral studies at the University of

Glasgow. Each presented a paper at the conference, and I am now happy to

introduce Megan Coyer to our web site. Her article appeared in The

Drouth, Scotland’s top cutting-edge periodical, one I eagerly await

arrival of at Waverley House. Of interest for those of us in the

metropolitan Atlanta area, Megan “spent some time in Atlanta as an

undergraduate working in the psychiatry department at Emory University”.

Later, I hope to bring you the papers of the other two outstanding doctoral

candidates - Jennifer Orr and Pauline Anne Gray.

A heads-up to any university wanting to enlarge or start

a Scottish Studies department. Any one of these young ladies would be a

great candidate, and it does not hurt that the three are also well versed in

Robert Burns after having studied at the University of Glasgow under the

direction of two of Scotland’s foremost authorities on Burns and Scottish

literature – Dr. Gerry Carruthers and Dr. Kirsteen McCue. I wish my alma

mater would go in that direction as I know where they can get a rather

choice selection of Scottish books and several very rare books on Robert

Burns as well.

Megan Coyer is a doctoral candidate at the University of

Glasgow in the Department of Scottish Literature under the supervision of

Dr. Kirsteen McCue and Dr. Gerard Carruthers and is the recipient of the

Faculty Overseas Research Scholarship. She earned an M. Litt. with

distinction in Scottish Literature from the University of Glasgow in 2006.

In 2005, she earned a B.S. in Neuroscience with Honours from Lafayette

College in Easton, Pennsylvania. Her current research draws upon her

scientific background, as she is working to contextualize the writing of

James Hogg (1770-1835) within the popular scientific culture of the early

nineteenth-century. She has a particular interest in the fictional and

popular medical writing of the Glaswegian physician-writer, Robert Macnish

(1802-1837) and his inter-textual connections to Hogg.

Her most recent publications are:

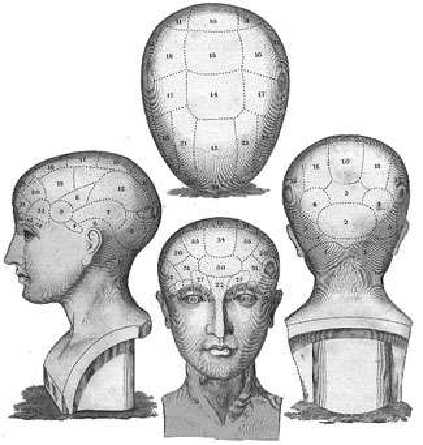

'The

Phrenological Dreamer: The Popular Medical and Fictional Writing of Robert

Macnish (1802-1837)', in The Proceedings of The Apothecary's

Chest: Magic, Art, & Medication, The University of Glasgow, 24 November

2007 (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press).

'Disembodied

Souls and Exemplary Narratives: James Hogg and Popular Medical Literature',

in Liberating Medicine, 1720-1835, ed. by Tristanne Connolly and

Steve Clark (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008), pp. 127-140.

'The Literary

Empiricism of the Phrenologists: Reading the Burnsian Bumps', The Drouth,

30 (Winter 2008), pp. 69-77.

Megan with the replica of Burns skull presented

to Dr. Ross Roy by Scotland's Colin Hunter McQueen. Dr. Roy brought the

skull back on his last trip to Scotland.

The Literary Empiricism of the Phrenologists: Reading the

Burnsian Bumps

By Megan Coyer

Department of Scottish Literature, University of Glasgow

On the 8th

of November 1830, Dr. Disney Alexander, physician to the General Dispensary,

and the Pauper Lunatic Asylum, in Wakefield, read an essay before the

Glasgow Phrenological Society. The paper was on the phrenological

development of the poet Robert Burns, and Dr. Alexander illustrated 'his

opinions with the incidents of his life, and numerous passages from his

writings.’

This analysis predates the postmortem phrenological examination of Burns's

skull by nearly four years. No record of the content of this essay has

survived, but the fact that such an analysis took place emphasizes, first,

the high level of phrenological interest excited by the poet and, second,

the dominant role of biography and literary criticism in informing the

evaluation. Burns was a character very much alive in the public imagination

– a natural genius, the 'heaven-taught ploughman', who was anything but an

angel. The vividness of this public image made him a fascinating and

strategically useful character to the phrenologists, as they sought to

confirm the basic tenets of their science by establishing a correlation

between the external protrusions of the skull and the character of the

individual. Scotland was the stronghold of the phrenologists in the

nineteenth century, and perhaps no character was so well-known to the Scots

as Burns. However, the heavy reliance on narrative evidence, including

biography, letters, and poetry, in reading the Bursian bumps, reveals the

phrenological analysis to be a strange mutation of literary empiricism

rather than an empirical science of the mind. Dr. Alexander again appeared

before the Glasgow Phrenology Society on December 17th 1834 to

read an essay “On the Moral Character and Cerebral Development of Robert

Burns”, at which time Mr. Andrew Rutherglen donated a cast of the poet to

the society. We may safely assume that his evaluation of the cast was

presented as a confirmation of his prior observations based solely upon

narrative evidence.

Dr. Alexander

appears to have had a pension for imaginative phrenological evaluations. In

'A Lecture on Phrenology, as Illustrative of the Moral and Intellectual

Capacities of Man' (1826), he focuses primarily on the applicability of

phrenology to characters within literary texts:

Those, who have studied the

subject, and who have, consequently, accustomed themselves to think

phrenologically, are able, in all cases of real character, even the

most anomalous, to discern that combination of the Organs, which produced

the manifestations perceived: and, whenever a character is well, or

accurately, defined, tho' existing merely in the Imagination of the

writer, they have no difficulty or hesitation, in applying to its

development the same mode of analysis.

In the lecture, the works of

Shakespeare are drawn upon as containing acutely naturalistic depictions of

human character, and 'Phrenology is shown to be in unison with

Nature, by its consistency with Nature's portraits, as drawn by this

masterly hand.'

The subject is not here exhausted for Alexander. He claims to have composed

nine lectures on the application of phrenology to characters in

Shakespeare's plays and also refers to his utilization of Shakespearean

characters in what could only be deemed a game of phrenological charades to

entertain some particularly lucky ladies at social gatherings! Similarly,

in Phrenology in Relation to the Novel, Criticism, Drama (1848), John

Ollivier writes of the ability to read phrenological character from natural

artistic renderings, as 'Shakespeare lived and wrote before Phrenology was

discovered, and he understood human nature as well as Mr. Combe.'

Ollivier here refers to George Combe (1788-1858), the most important

propagator of phrenological ideology in early nineteenth century Scotland

and, as we will see, a key player in the phrenological evaluation of Burns.

The phrenological movement

was an early moment of methodological intersection between literary analysis

and empirical scientific investigation. Phrenology was based upon the

correlation between the size of external protrusions, or 'bumps', of the

skull and the power of specialized organs of the brain, and each organ

corresponded to a specific mental faculty. The essential tenets of Combe's

phrenology were: (1) The brain is the organ through which the mind is

manifested during life; (2) The brain is not a singular organ, but rather

consists of multiple organs with distinct functions; (3) All other factors

being equal, the power of the organ can be estimated from its size. These

factors included temperament and external circumstances, such as education;

and finally, (4) The size of each organ can be ascertained by an examination

of the skull. The latter two tenets were the most controversial, and, in

their defense, Combe appealed to the continual collection of data - external

measurements as well as biographical data to evidence the manifestation of

specific mental faculties in the subject's personal character. Executed

criminals were often examined, as their skulls were readily obtainable and

their personal history and moral constitution established before a court of

law. Burns had one crucial thing in common with the executed criminal – his

personal history and moral constitution were well-traversed territory in the

public imagination. Robert Cox (1810-1872) of the Edinburgh Phrenological

Society, who provides the most detailed and narratively informed

phrenological evaluation of Burns based on Combe's original measurements,

explains:

It may be affirmed without

fear of contradiction, that there is no individual whose character and

history are better known in Scotland than those of Robert Burns. To

Scotchmen, even in the most distant parts of the world, his works are hardly

less familiar than the sacred writings themselves. The minutest incidents of

his life have been recorded, commented on, and repeated almost to satiety,

by a succession of talented biographers

However, unlike the cranial

refuse of capital punishment, the immortal bard's skull was not quite so

easily transformed into scientific commodity.

At the time of

Burns’s death in 1796, phrenology was not yet in existence, and hence,

unlike many of the celebrated Scots and English writers of the following

century, no cast of his skull or face was taken during his lifetime. In 1830

John McDiarmid, president of the Dumfries Burns Club and editor of the

Dumfries Courier, retrospectively reports the events surrounding the

first exhumation of Burns’s body that took place on September 19th

1815. Under the cover of night, the body was disinterred from its original

plot, which had been marked by a modest monument raised from the widow’s own

slender means, and moved to the site of new grand mausoleum, still within

the walls of St. Michael’s Churchyard. He describes the uncanny preservation

of the body, its exhibition of the 'features of one who had newly sunk into

the sleep of death – the lordly forehead, arched and high – the scalp still

covered with hair, and the teeth perfectly firm and white', and the awe

experienced by the select bystanders. He then laments:

Phrenology, at that time, had

not become fashionable, or rather was cultivated under a different name, and

as no such opportunity can occur again, it is perhaps to be regretted that

no cast was taken of the head for the benefit of the admirers of that

science.

But it was only a matter of

time until just such an opportunity did arise, and it was McDiarmid, along

with Adam Rankin and James Kerr, who was to play a key role in the macabre

transactions that continue to fascinate Burnsians today.

On the 31st

of March 1834, following from the death of Burns's widow Mrs. Jean Burns,

the mausoleum was re-opened, and Burns’s body was once again exhumed with

the express purpose of obtaining a cast of the skull. The circumstances

surrounding the exhumation were reported in the Dumfries Courier by

the surgeon Dr. Archibald Blacklock, who was responsible for the handling of

the skull, and his report was republished within Cox’s essay in the ninth

volume of the Phrenological Journal. Blacklock’s report focuses on

the professional care taken in both respectfully handling the skull and

obtaining an accurate plaster of Paris cast, and was most probably published

in order to quell accusatory parallels to the anatomical grave-robbers in

the wake of the Burke and Hare scandal. In a letter to Combe, McDiarmid

expresses his concerns over an article published in The Spectator

which he perceived as slanderous, and he defends an apparent

post-mortem dress-up session as 'it was not until Dr. Blacklock had tried

the skull in his own hat any one else presumed to act on it.'

Regardless of the surrounding controversy, Combe was profuse in his

appreciation for McDiarmid's actions, and in a statement revealing his faith

in the future propagation and ultimate vindication of his brain-based

philosophy of mind, he writes:

You & Sir Henry Jardins, who

preserved for us a cast of King Robert Bruce's skull will be honoured

hereafter for your enlightened contributions to the philosophy of mind, in

these relics, while a just indignation will be dealt out to the memory of

the men who buried Sir Walter Scott's skull without permitting a cast to be

taken, & who spread unfortunate reports that his brain was small.

This extract also points

towards an anxiety that the phrenological readings of well-known figures

match-up to their characterisation in the public imagination. The relatively

small hat size of Sir Walter Scott was touted by the anti-phrenologists as

evidence against the correlation between size and power. Combe was able to

finally rebuke these charges in 1858 when he discovered that a cast was

indeed secretly made of Scott's head following the post-mortem examination

of his brain in 1832. According to Combe's journal entry for 30th

April 1858, the sculptor Mr. John Steel was given the original cast by the

Scott family in order to fashion a facsimile in bronze. Although he was

instructed to keep it 'under lock & key', Steel provided Combe with

measurements that enabled him to account for the small hat size as follows:

Ideality, Cautiousness,

Concentrativeness, and Causality, on which in him gave the

circumference of the lower margin of the hat, were all only moderately

developed, and a mass of brain rose upwards into the hat & stood below it.

The report that the brain “was not large”, cannot have been true.

The authorial hat size

controversy may well have been the inspiration for Blacklock's impromptu

fashion show. However, one can imagine a self-comparative motivation as

well. Who wouldn't want to know if their brain is as big as Burns's?

However, if Burns's skull did not indicate a large and therefore powerful

brain, the phrenological doctrines would receive a serious blow.

Even an article

in the Manchester Times & Gazette, reporting on the recent

acquisition of the Burnsian casts, presents the phrenological assessment of

the poet as inherently risky:

Casts from the skull of Burns

have afforded phrenologists and the Public an opportunity of testing the

truth or falsity of Phrenology. The mental character of the poet are so

strongly marked, and the outlines so broadly defined, that we should at once

expect either a very striking accordance or discordance with his cerebral

organization.

The existence of

phrenological estimations, such as that of Dr. Alexander, formulated purely

upon an analysis of the life and works, would not have been particularly

helpful to the phrenological cause if the bumps did not match-up. Robert Cox

also claims to have presented an essay before the

Edinburgh Ethical Society in the winter of 1833 which contained a

phrenological evaluation of the poet based entirely upon biographical and

literary analysis. These evaluations, which read the bumps from the books,

rather than from the head, may have led to the

anti-phrenological accusations contradicted in a footnote to Cox's essay:

A report has been widely

circulated, that, long before the present cast was obtained, the

phrenologists had made an imaginary bust of Burns, and adduced it in support

of their doctrines. Nothing can be

more unfounded.

Cox refers to his previous

analysis to show that the physical evaluation of the cast is consistent with

a phrenological analysis based solely on narrative evidence, and thus,

indicates the foundation of phrenology in nature. Burns's bumps are

victoriously declared 'a striking and valuable confirmation of the truth of

Phrenology.'

The copyright of

the cast was legally conferred to McDiarmid, and, initially, he was cautious

to the point of paranoia in preventing the creation of pirated copies of the

relic, which were clearly in high demand. He writes to Combe:

I have had applications from

Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, Ayr, &, for Casts; but I will take time for

due deliberation. The letter from Glasgow struck me as suspicious, &, though

a handsome bribe was sent, I declined the offer.

On the morning of the 20th

of April, Combe received the first two copies of the cast, one for personal

use and one to forward to the Edinburgh Phrenological Society. He wasted no

time in forming his estimates of the sizes of the cerebral organs, writing

to McDiarmid the same morning that:

the size is great, so you

have stated; the organs of the animal propensities are very strongly

indicated, but there is an agreeably powerful development of the sentiments

of Benevolence, Ideality, Wonder, & Imitation; considerable Veneration; &

average Conscientiousness; so that the higher qualities were combined in

burns in great vigour with the lower. The intellect is highly respectable

but inferior to the feelings. He had the elements of all that is bad & good

powerful, & an intellect not quite adequate to their proper control, but

very nearly so. All this is the language of the cast, & I think it

conformable to with his history.

This initial evaluation is

characteristic of the numerous evaluations that follow, as the brain of the

bard is posited as a site of intense psychological warfare – his powerful

animal propensities and moral sentiments struggling for dominance in

well-documented and poetically rendered battles. The following month, in a

letter to Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin, Combe appeals to 'A Prayer

in the Prospect of Death' to evidence that his poetry and biography, 'can

scarcely be understood by those who do not know phrenology':

Thou

know’st that Thou hast formed me,

With Passions wild and strong;

And list'ning to their witching voice

Has often led me wrong.

After

're-perusing the life of Burns', Combe finds that 'it is impossible to look

on the great mass of the organs of the propensities without feeling that

[blot] verse evidences a literal truth.'

An official evaluation by Combe is published in the Phrenological Journal

in June 1834, and this is followed in the next

number by Cox's more illustrative analysis. The table below contains Combe's

estimations, and these are also used by Cox in his analysis.

The preferment

given to the biographical evidence in Burns's case was justified by the

external measurements which indicated a fairly equal balance between animal

and superior moral faculties. Indicative of the continued currency of the

medieval concept of 'The Great Chain of Being' into the nineteenth century,

the phrenological organs were divided into those faculties shared by both

humans and lower animals and those unique to mankind. The propensities,

such as 'Amativeness' (organ of sexual passion), 'Adhesiveness' (organ of

attachment), and 'Combativeness', and the inferior sentiments, such as 'Love

of Approbation' and 'Self-Esteem', were common to both man and beast, as

were the intellectual faculties, which allowed for a functional relationship

with the external environment. For example, the phrenological writer, Robert

Macnish, notes that 'Love of Approbation' is 'active in the monkey, which is

fond of gaudy dresses.'

The superior sentiments distinguished man as a moral being, and included

such faculties as 'Benevolence', 'Veneration', 'Firmness',

'Conscientiousness', and 'Hope'. In some persons, the animal propensities

and inferior sentiments might be so predominant as to render them innately

unfit to function in civilised society – a broad-based skull, indicating

large animal propensities, was a red flag to steer clear. In contrast, the

moral sentiments might predominant to the extent that a person could not

help but live a righteous life. However, the vast majority of persons fell

into a third category, in that moral and animal faculties displayed a degree

of balance and hence produced conflicting emotional responses. Such persons

are characterised by Cox: 'In the heat of passion they do acts which the

higher powers afterwards loudly disapprove, and may truly be said to pass

their days in alternate sinning and repenting.'

The behaviour of such persons was particularly susceptible to external

factors, and such was the case of Burns. Thus, within the construct of a

potentially biologically deterministic evaluation, the moral indiscretions

of the bard are in fact externalised.

Not surprisingly,

Burns's well-known proclivities towards the opposite sex are of keen

interest to the phrenologists. It may however be surprising to find that

'Amativeness', the organ of sexual passion, is estimated to be only 'rather

large' and receives 16 out of 20 in the numerical ranking scale (the average

rank for a Burnsian animal propensity being 18.25). Fortunately for the

phrenologists, the organ of 'Adhesiveness', which is found to be very large

(20 out of 20) in Burns, was identified as the seat of true affection in

previous phrenological articles. Macnish later writes that an abuse of the

organ of 'Adhesiveness' leads to a proneness to form 'absurd and romantic

attachments', and 'unless there are eminent moral qualities to ensure

permanence, the feeling is seldom of long duration.'

Combined with Burns's large organs of 'Ideality', 'Love of Approbation', and

'Secretiveness', this is said to account for the poet's attachment to the

feminine sex. None of the faculties, when properly controlled, are

considered inherently bad, and Cox, homing in clearly on Burns's biography,

writes:

Notwithstanding the

licentious tone of some of his early pieces, we are assured by himself (and

his brother unhesitating confirms this statement), that no positive vice

mingled in any of his love adventures until he had reached his twenty-third

year.

Cox continues to draw upon

Lockhart's Life of Robert Burns (1828) and identifies the period at

Irvine in 1781-2 as the external circumstance which served as the turning

point for Burns's behaviour, in other words, the circumstance that allowed

his animal propensities to wheel out of the control of his moral faculties.

According to his own accounts and that of his brother, Gilbert, he was here

exposed to the licentious scenes of dissipation and unabashed womanising

which led him down the path to a freer mode of living. Frederick Bridges, in

his 1859 evaluation, follows a similar line of reasoning, as he writes that

'the situation of an exciseman was the most unfortunate that could have been

selected for a man like Burns.'

In the 1878 evaluation by Nicolas Morgan, we see the same appeal to

Lockhart's emphasis on the negative impact of his associates at Irvine, but

now the circumstances of the poet's life are viewed as vitally linked to his

lyrical productions:

the poetic gift is so marked

in the poet's skull, the world is much indebted for his charming lyric

productions, to his dominant love and social instincts, and to the situation

in life in which circumstances placed him.'

This is in stark contrast to

Combe's heartfelt regret of the 'unfavourable circumstances' in which the

poet was placed throughout his life, as he conjectures:

If

he had been placed from infancy in the higher ranks of life, liberally

educated, and employed in pursuits corresponding to his powers, the inferior

portion of his nature would have lost part of its energy, while his better

qualities would probably have assumed a decided and permanent superiority.

Two major factors appear to

come into play in determining this differentiation of opinion. First, by

1878 Burns's image as the icon of class-transcendent genius, the poet of 'A

Man's a Man for a' That', was well crystallised and would most probably

quell any conjecture as to what more he might have accomplished if born

within the higher ranks. Secondly, Combe most probably personally

disapproved of what he would consider the baser aspects of Burns's poetry,

in other words, those aspects inspired by his animal faculties. Not only was

poetry used to evidence the active faculties within the author's brain, but

it was also viewed as an effective method of stimulating the corresponding

faculties in the brain of the reader. Hence, the great size of the organs of

'Combativeness', 'Destructiveness', and 'Self-Esteem' which Combe believed

inspired 'Scots wha hae wi' Wallace bled' would be systematically stimulated

and thus strengthened by reading this poem. This of course could be useful

in times when patriotic feelings were necessary, but overall, such poetry

was counterproductive to Combe's personal imperative towards the formation

of a more enlightened populace. Similarly, Combe disapproved of capital

punishment on the grounds that the violent public spectacle stimulated the

very qualities within the spectators that had necessitated the execution –

most probably, 'Destructiveness'. While some of Burns's poetry, such as 'To

a Mouse', would stimulate the organ of 'Benevolence' (considered the largest

of Burns's moral faculties by Combe and all later evaluations I have

identified), the great power of both animal and human faculties translated

into a body of poetry that evinced the dualistic aspect of the human

condition, and according to Combe's less guarded private correspondence, at

times, it was 'the unfortunate vigour of his animal propensities, which

disappointed defeated the language of his higher powers.'

The relatively

large size of all the organs of the brain, and hence the overall size of the

brain which exceeds 'the average of Scotch living heads', combined with a

naturally powerful and active temperament, led to a conglomeration of

powerful mental faculties. According to Cox, this confirms the philosopher

Dugald Stewart's evaluation of the source of genius for the poet:

But

all the faculties of Burns's mind were, as far as I could judge, equally

vigorous; and his predilection for poetry was rather the result of his

enthusiastic and impassioned temper, than of genius exclusively adapted to

that species of composition. From his conversation, I should have pronounced

him to be fitted to excel in whatever walk of ambition he had chosen to

exert his abilities.

The location of his genius is

not discrete, but rather disperse, and hence not subject to the

externalising strategy applied to his moral shortcomings. John Williams

Jackson, popular lecturer on phrenology and mesmerism, is reported to have

given a lecture on 'The Phrenological Development and Mental Characteristics

of Burns' in Glasgow on the 7th of December 1864. According to a

report of the lecture in The Caledonian Mercury, Jackson harked upon

the overall size and vigour of Burns's brain to justify the bard's universal

appeal, as 'Burns, indeed, stood above the ordinary range of men of genius

and poets, in virtue of the fact that he was not merely a literary man but a

universal man.' Jackson critically locates both male and female, animal and

human, within the universal bard who is thus ascribed the Shakespearean

ability to faithfully delineate characters from nature:

He was possessed of the

passions and impulses of the most powerful man, and yet at the same time was

endowed with the delicacy and intensity of the most refined woman, while he

also had highly elevated moral principles and superior intellectual

faculties. Burns, in fact, was the most thoroughly universal man who had

appeared since the days of Shakespeare.

Burns's understanding of

human nature, if we may be allowed to conveniently conflate Ollivier and

Jackson's arguments, like Shakespeare's, may compare with that of Mr. Combe

himself, and this understanding is viewed as rooted in his own

experience with the viscitudes of emotion. Frederick Bridges uses 'The

Bard's Epitaph' to illustrate the dizzying range of active faculties in

Burns:

“Owre fast for thought, owre

hot for rule,” running “life's mad career wild as the wave,” refers to his

large and very active propensities. His large self-esteem and love of

approbation are shown - “Owre blate (too modest) to seek, owre proud to

snool.” His large social and domestic feelings, which “keenly felt the

friendly glow and softer flame.” We have his moral feeling and mental powers

indicated - “Can others teach their course to steer” - “quick to learn and

wise to know.” The warning in the concluding stanza - “Know, prudent,

cautious self-control is wisdom's root” - shows great benevolence, and

consciousness of low firmness, which his skull indicates.

Clearly the continual appeal

to poetry to confirm the cranial measurements can lead to a reductive

reading of Burns's work, but, at the same time, and perhaps most overtly in

Jackson's evaluation, Keats's notion of 'the cameleon art' of poetry is very

much alive, as through his strong endowment of all the mental faculties,

Burns could presumably step into the proverbial shoes of the other with

natural ease. This evaluation does accord with John Wilson's literary

assessment of the genius of Burns published in 1819 in Blackwood's

Edinburgh Magazine, in which he writes 'that it was often the

consciousness of his own frailties that made him so true a painter of human

passions'.

The heavy

dependence on narrative evidence in the phrenological evaluations of Burns

naturally leads them into the realm of literary criticism, and as we have

seen, these evaluations in fact began from imaginative premises. According

to phrenological writers, such as Ollivier and Alexander, the major

distinction of the phrenological literary assessments from general literary

criticism of the period is their formulation according to a set of rules

derived from an empirical study of Nature, i.e. skulls. By moderns

standards, the empirical derivation of these rules is of course

questionable, but the phrenologists did gather physical data available to

repeated analysis. Burns's skull provided just such a data set. The cast of

the poet's skull, despite McDiarmid's initial protectiveness, made its way

into the mass produced phrenological lecture sets sold by Anthony O'Neil,

and thus truly entered into the public domain. Later analyses appear to

devolve into entertaining spectacles. For example, Jackson's 1864 lecture in

Glasgow 'was further enhanced by the singing at intervals of some of Burns's

songs, which were very effectively rendered by Mr. G. D. Bishop', and at the

close of the lecture, Jackson performed phrenological analyses on audience

members. Combe believed such blatant showmanship degraded the scientific

authority of phrenology, but the public's appetite for cultural iconography

and strange feats of science combined to make the phrenological lecture

inherently amusing. However, the more saturnine empiricism of the initial

evaluations remained in currency, as both Combe and Cox's essays were

re-published together in a pamphlet in 1859 in honor of the centenary

celebration of Burns's birth. The publisher's preface presents phrenology as

an inherently fairer and more accurate approach to the study of such an

important public character:

At this hour the name of

Burns is in every man's mouth, his praise is on every tongue; the present

may, therefore, be deemed an unsuitable time to ask a study of his

character, - the festive rather than the scientific commanding popularity.

Yet we make no apology for the publication of the following Essay: it can

speak for itself now, and will bear to be investigated and contemplated in a

time of calmer leisure. Indeed the providing of a worthy memorial of the

great bard, which, with its other qualities, has this to recommend it, that

its material is drawn from a reliable source, and its deductions directed by

science [...] To set forth the true character and depict the numerous phases

of a life such as that of Burns, is work for a philosopher – but without a

correct philosophy no sage could be successful in it.

Today, phrenology is

relegated to the lower divisions of the history of science – as an

embarrassing, yet still amusing, methodological dead-end – an open

invitation for quacks at best and racial imperialists at the very worse.

However, the phrenological analyses of Burns stand out as uniquely

representative of the fluid exchange, and all-in-all, the lack of a real

distinction, between literary and scientific thinkers in the early

nineteenth-century. Rather than simply providing a scientifically informed

character study of a man who happened to be a poet, the first analyses by

Cox and Combe sought to utilize the strength of the public image of Burns to

forward the authority of the foundational tenets of their celebrated new

science of the mind. But in this case, the solidity of the skull was read

through, rather than against, the vivid spectre of Robert Burns.

Megan delivering her paper at the University of

South Carolina's April conference on Robert Burns.

A. Stewart, 'Publisher's Preface', in 'An Essay on the Character and

Cerebral Development of Robert Burns, by Robert Cox. (Reprinted from

the Phrenological Journal for September, 1834) With Observations on

the Skull of Burns, by the late George Combe.' (Edinburgh: A.

Stewart, Phrenological Museum, 1859), pp. 3-4.

|