|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Several years ago while attending a symposium on Robert

Burns at Emory University in Atlanta, I met a delightful man. He was a

featured conference speaker and when he had finished his presentation, I

understood why. This humble and courteous man is a gifted writer, scholar,

professor, author, speaker, student, and conversationalist. His name is

Kenneth Simpson. He visits Dr. G. Ross Roy at the University of South

Carolina on a regular basis and, in turn, I usually try to find time for the

drive over to Columbia to visit with Ken, and maybe share a meal or two.

Not only does Ken know Robert Burns, he knows how to

deliver the message of Burns. It has been my joy to swap emails with him

over the years. I have reviewed his best selling book, Robert Burns,

on my website, A Highlander and His Books. More importantly,

I consider him to be my friend. Here is a brief account of some of his

achievements…

Ken Simpson was Founding Director of the Centre for

Scottish Cultural Studies at the University of Strathclyde and organizer of

the Burns International Conference held there annually from 1990 to 2004. He

has twice been Neag Distinguished Professor of British Literature at the

University of Connecticut and twice W. Ormiston Roy Research Fellow in

Scottish Poetry at the University of South Carolina. Recently appointed

Honorary Professor in the Department of Scottish Literature at Glasgow

University, he is currently President of the Eighteenth-Century Scottish

Studies Society. Ken’s various international engagements recently have

included discussions on Burns with William McIlvanney in St. Petersburg and

giving a paper on Smollett at the Twelfth Congress of the Enlightenment in

Montpellier. He also currently appears in a video accompanying the NLS

touring exhibition on Burns entitled ‘Zig-Zag Man’.

Ken’s publications include The Protean Scot: The Crisis of

Identity in Eighteenth-Century Scottish Literature; Burns Now;

and Love and Liberty: Robert Burns – A Bicentenary Celebration. He

is editing, with Ross Roy, Correspondence with Burns and is working

on a study of Burns’ letters.

In keeping with the spirit of the 250th

celebration of the birth of Burns, Ken has agreed to share the following

article about the bard.

What Burns Means to Me

Kenneth Simpson M.A. Ph.D, FRSA, FEA

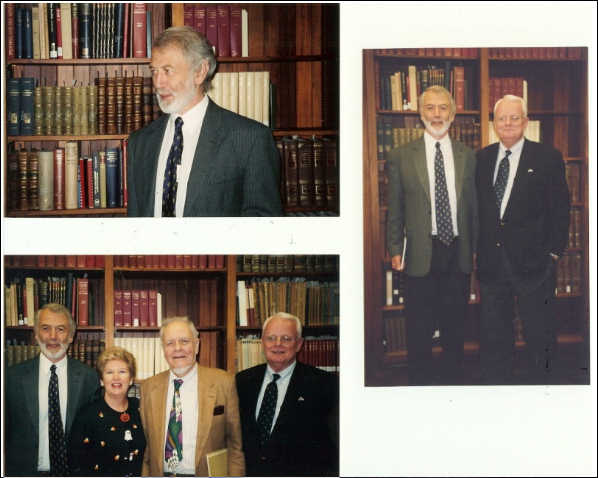

Left top: Dr. Ken Simpson, Left bottom: Dr. Ken

Simpson, Susan Shaw, Dr. Ross Roy, Frank Shaw,

Right: Ken Simpson, Frank Shaw

The location – St Petersburg, the occasion – a visit by

Scots including William McIlvanney to celebrate the work of Robert Burns.

One enthusiast stands out, Valentina, a noted poet in her city of Perm.

Though ailing she has travelled 1,000 miles to pledge her kinship with

Burns. Likewise, Frederick Douglass published his Narrative of a Fugitive

Slave in 1845 and visited Alloway testifying to his spiritual affinity

with Burns ‘who taught me that “a man’s a man for a’ that”’.

Burns is an outstanding creative talent, a national icon,

an international phenomenon. Apart from two forays across the border Burns

remained rooted in Scotland, but his work has circled the globe. His poems

and songs transcend barriers of race, class, culture, and creed. The values

that he espouses make him world-renowned: ‘My two favourite topics [are]

Love and Liberty,’ he wrote. His impact on popular consciousness is

reflected in the recurrence in everyday speech of lines such as ‘man’s

inhumanity to man’; ‘the best-laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men’; ‘To see

ourselves as others see us’; and ‘ man to man the world o’er/ Shall brothers

be for a’ that’.

Maria Riddell wrote of Burns’s ‘sorcery’ with words. For

centuries poets compared their love to a red rose; simply by repetition of

‘red’ Burns conveys the intensity of his love. For the aged patriot betrayed

by the Union of 1707 the Scottish Commissioners are ‘a parcel of rogues’,

packed together, herd-like, for safety. The lover surveys the beauties at

the dance, then conveys where his heart lies in the line MacDiarmid deemed

Burns’s finest, ‘Ye are na Mary Morison’. In vernacular Scots he habitually

hits the mark: in ‘She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum/ A blethering,

blustering, drunken blellum we hear Tam’s wife’s flyting; and when Burns

describes the witches’ party the lines themselves dance.

Henry Mackenzie did Burns no favours with the tag, ‘this

Heaven-taught Ploughman’, implying that divine inspiration enabled the

untutored rustic to hold a mirror to his experience. Burns’s brilliance lies

in the imaginative transformation of the local and specific into the

universal: a sheep falling on its back enables him through the words of the

dying Mailie to highlight the habit of contradicting our general principles

when we apply them to ourselves; a louse on a girl’s bonnet prompts an

alternative sermon on the dangers of aspiration; the rejection of William

Fisher’s charges against Gavin Hamilton triggers the self-revelation of the

closed mind of Holy Willie, absurd in its limitations and awesome in its

implications – here is one of the great texts of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Burns’s powers of both sympathy and empathy are

remarkable. He inhabits that mouse in the first line of his poem; he becomes

Mary, Queen of Scots in her ‘Lament’; he speaks as the pining young women in

the songs, ‘Logan Water’ and ‘Ay Waukin, O’. He demystifies the Devil by

addressing him as a crony, and Death is sympathetically humanised in ‘Death

and Dr Hornbook’. Time and again Burns’s essential humanity shines through.

We know him because he knows us.

Unsurprisingly, Burns has been recruited for the

Homecoming. But might the celebrations encompass some of our other great

writers? We Scots have a worrying fondness for single vision. Teaching

Scottish literature in the States, I found students very positive about the

poetry of Allan Ramsay, Iain Crichton Smith, Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard.

‘Hey, you guys have much more than Burns’, said one student, ‘You should

tell the world.’ We should start by telling ourselves.

Burns was as sociable as he was generous. Is he perhaps

getting lonely in the Scottish pantheon? Might he not enjoy the company of

the subtle John Galt, mistress of the mysterious, Margaret Oliphant, the

superlative stylist, RLS, or the scandalously neglected Tobias Smollett,

whose ‘incomparable humour’ he so admired? What a party that would be! (FRS:

3.04.09) |