Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

It has

been my desire for some years now to have an article by Dr. Patrick

Scott on this website and here he writes on the relationship of Robert

Burns and James Hogg, “The Ettrick Shepard”. This article adds

additional depth and another dimension to the pages of the Robert

Burns Lives! Website.

Let me

introduce you to Dr. Scott if you have not had the opportunity of

meeting him. Patrick is Director of Special Collections (Rare Books),

Thomas Cooper Library, as well as Professor of English at the University

of South Carolina in Columbia. Although he says, “I’m not by training a

Burns scholar”, he is, in his own right and as my Burnsian friends will

testify, a Burns scholar and is highly respected by those who profess a

love and scholarship for Burns.

He is my

friend and has helped immensely in my research regarding the bard.

Patrick has given me invaluable advice regarding my Scottish library and

particularly the books in my Burns library. Actually, there are no

high-priced books in my library on or about Burns that Patrick, along

with his senior colleague, Ross Roy, has not given me advice on,

including the Kilmarnock purchased a few years back. Additionally, there

are few speeches or articles that I have given or written over the last four

years that have not included his imprint in one form or another.

Unbeknown to Patrick, in our conversations, phone calls and emails, I

have picked up many ideas and put them in print or used them in

speeches. It is a distinct privilege for me to welcome Dr. Scott to the

pages of Robert Burns Lives! (FRS: 6-11-08)

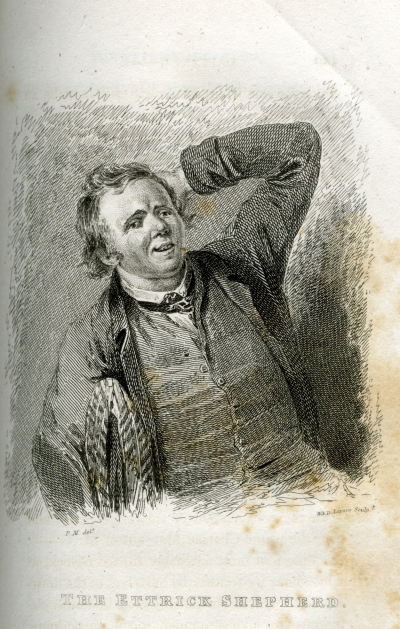

ROBERT

BURNS AND JAMES HOGG:

THE PLOUGHMAN-POET

AND THE ETTRICK SHEPHERD

By Patrick Scott

What was it

like for a younger Scottish poet, in the next generation after Robert

Burns? In the few short years between the Kilmarnock edition in 1786

and the poet's death in 1796, Burns had gained international

recognition, not only in Scotland and the British Isles, but in America

and Europe. In the years after his death, publishers and editors and

biographers and anecdotalists all had their say. For a younger writer

like James Hogg the Ettrick Shepherd (1770-1835), the fame of Burns was

both inspiration and challenge. Burns's influence is part of Hogg's

story, but the influence was reciprocal: Hogg’s own image influenced how

his early nineteenth-century contemporaries and subsequent generations

regarded Burns.

Very few aspects of literary history have changed as much in the past

forty years as the study of what we used to call influence. Old

fashioned literary historians like me love to trace influence, but

traditional literary study teaches us to prize originality above

everything, and the most original poets struggle hardest against the

most original of their predecessors, with lasting consequences for how

the predecessors are understood. James Hogg’s struggle against Burns’s

influence gives some revealing clues to the character of Burns’s

achievement, and the contemporary reviews of James Hogg’s poetry provide

a new kind of evidence, untapped by Burns scholars, about how Burns’s

poetry was being read in the decades after his death.

James Hogg was born in 1770, so he was about ten years younger than

Burns, but he outlived Burns by nearly forty years, surviving and

writing till the mid-eighteen-thirties. Hogg was not only a poet. His

best-known work now is his remarkable psychological novel, the

Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), about

a Calvinist ordinand who murders his handsome cosmopolitan brother, a

crime story told twice over from different perspectives. As well as

writing several other novels--The Brownie of Bodsbeck (about the

Covenanters), The Three Perils of Man, and the The Three

Perils of Women, Hogg was also a prolific short-story-writer and

essayist. But in Hogg’s lifetime, and indeed in his own estimation, Hogg

was one of the great Scottish poets, legitimate heir to Allan Ramsay,

Robert Fergusson, and to Robert Burns himself. By 1819, Blackwood’s

Edinburgh Magazine could plausibly describe Hogg as Burns’s “only

worthy successor.”

From the very beginning of Hogg’s career, Burns was his model and hero.

Even more than William Burnes, Hogg’s father had been over-ambitious, a

sheep-farmer in the Scottish Borders south of Edinburgh, who took on too

much risk in the agricultural expansion of the late 1700s. Unlike

William Burnes, Hogg’s father lost literally all the family’s resources,

and his son went off to work at the age of six, herding cows. Unlike

Burns, too, James Hogg had very little schooling, though during his teen

years one of his employers lent him books to read. When he turned poet

in his twenties, he later recounted, even the physical process of

writing had to be painfully learnt over again.

Perhaps in conscious imitation of Burns’s famous letter to Dr. John

Moore, Hogg left us a detailed autobiographical record of how he became

a poet, in a long letter he addressed to Walter Scott in 1806 printed as

the introduction to his book The Mountain Bard (1807). Hogg was

a compulsive autobiographer: as he later wrote, “I like to write about

myself: in fact, there are few things which I like better.” And as an

autobiographer, Hogg could be both imaginative and inventive, especially

where Burns was involved; he routinely claimed to have been born on

January 25th, Burns’s birthday, and was terribly disappointed when his

parish minister proved to him from the registers that this wasn’t so.

(It seems almost incidental that he got the year wrong, too.)

Burns’s was not the first Scottish poetry Hogg encountered--as a

semi-literate teenager he’d struggled through Hamilton of Gilbertfield’s

Sir William Wallace and Allan Ramsay’s Gentle Shepherd--,

but when he did encounter Burns, at the age of twenty-seven, the impact

was immediate:

One day

during that summer [in 1797], a half daft man, named John Scott, came to

me on the hill, and to amuse me repeated Tam o’ Shanter. I was

delighted! I was far more than delighted--I was ravished! I cannot

describe my feelings; but, in short, before Jock Scott left me, I could

recite the poem from beginning to end, and it has been my favourite poem

ever since. He told me that it was made by one Robert Burns, the

sweetest poet that was ever born; but that he was now dead, and his

place would nevere supplied. He told me all about him, how he was born

on the 25th of January, bred a ploughman, how many beautiful songs and

poems he had composed, and that he had died last harvest, on the 21st of

August.

This formed

a new epoch of my life. Every day I pondered on the genius and fate of

Burns. I wept, and always thought with myself--what is to hinder me from

succeeding Burns? I too was born on the 25th of January, and I have much

more time to read and compose than ever ploughman could have, and can

sing more old songs than ever ploughman could in the world. But then I

wept again because I could not write. However, I resolved to be a poet,

and to follow in the steps of Burns.

Hogg did

indeed follow in the steps of Burns. His first book, Scottish

Pastorals, published in Edinburgh in 1801, used a subtitle, as Burns

had done in 1786, to draw attention to the language issue: Poems,

Songs, &c., mostly written in the language of the South [i.e. the

Scottish Borders, the south of Scotland]. Hogg’s best-received poem, “Kilmeny,”

from his volume The Queen’s Wake (1813), about a young Scottish

maiden who mysteriously disappears from her native glen into the spirit

world and returns to tell her vision, shows Hogg exploring his own

variant version of the supernatural territory Burns had explored in “Tam

o’ Shanter.” As with Burns’s work for Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum

and Thomson’s Select Collection, Hogg’s contribution to

Scottish literature included the recovery and editing of traditional

song, supplying ballad texts for Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the

Scottish Border, writing new poems for traditional airs in his

volume The Forest Minstrel (1810), and editing a

still-influential collection, The Jacobite Relics of Scotland,

published in two series in 1819 and 1821. One of the greatest public

triumphs of Hogg’s later years was his appearance in London as guest of

honour at a great dinner in London on Burns Night 1832, when he not only

speechified but brewed up the punch in Burns’s own punchbowl: as Hogg

complacently reported to his wife, “though the name of Burns is

necessarily coupled with mine, the dinner has been set on foot solely to

bring me forward.”

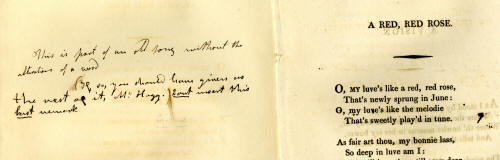

And Hogg’s writing career ended as it had begun, with Burns, for when he

died in 1835 publication in part-issue had recently started for a new

edition of Burns edited by Hogg and his fellow-poet William Motherwell.

(Incidentally, the G. Ross Roy Collection at the University of South

Carolina includes Hogg’s marked-up text of Burns, with copious

annotations in Hogg’s hand.) F. B. Snyder memorably dismissed Hogg’s

memoir of Burns in this edition as “perhaps the worst life of Burns

written before the twentieth century,” but the memoir has some revealing

strengths. Like Burns, Hogg had stood in his local church to be

admonished for fathering a child out of wedlock, and like Burns he had

been dismissed and caricatured as a drunk. Hogg strives to be realistic

without being judgmental, asserting that, forty years after Burns’s

death, “none but the most narrow-minded bigots think of his errors and

frailties but with sympathy and indulgence,” and “none but the blindest

enthusiasts deny their existence.” Moreover, in his concluding comments

on Thomas Carlyle’s famous essay about Burns, Hogg points out what would

increasing go wrong in Victorian commentary--an over-spiritualizing or

romanticizing of a poet firmly rooted in real social experience;

Carlyle, Hogg implies, simply doesn’t grasp Burns’s humor.

But Hogg’s best tribute to Burns’s influence is itself a poem, a moving

reminiscence of that first sense of bereavement forty years earlier,

when he had learnt at one and the same time both of Burns’s achievement

and of his death “last harvest”:

Ae night,

I’ the gloaming, as late I pass’d by,

A lassie sang sweet as she milkit her kye,

And this was her sang, while the tears down did fa’--

O there’s nae bard o’ nature sin’ Robin’s awa’!

The bards o’ our country, now sing as they may,

The best o’ their ditties but maks my heart wae;

For at the blithe strain there was ane beat them a’,--

O there’s nae bard o’ nature sin’ Robin’s awa’!

Burns,

then, served for James Hogg, as for a host of other humbly-born poets

both Scots and English for the next fifty or more years, as the

role-model who pointed them to the possibility of authorship.

Typically, when beginning poets are so strongly influenced by a

predecessor, they go through an extended process of accepting,

repressing, rejecting, and redefining that influence as they seek to

establish their own voice. The process can be persuasively analyzed in

psychological terms, as a struggle against the poetic father, but in the

case of Hogg and Burns, altered circumstances, not just individual

psychology, played a part in the development of poetic difference.

First, though Hogg shared Burns’s heritage of Scottish folk-song and

folk culture, he lacked Burns’s early education or extensive early

interaction with the literary and intellectual culture of late 18th

century Scotland. Burns had taken in the ideas of the Scottish

enlightenment from his friends at Tarbolton in his late teens, Hogg

encountered such thinking only as an outsider, only in his thirties.

Second, even in Burns’s brief lifetime, the Scottish political

atmosphere changed, from the democratic self-assertion of the

seventeen-eighties to the conservatism that followed the French

revolution. Hogg’s ties throughout his writing career were to cultural

traditionalism, so in some ways he was liberated by the movement of

literary fashion in the early years of the century away from political

debate. But cultural traditionalism brought him ties to Tory patrons

like Walter Scott or the Buccleuch family, and to Tory magazines like

Blackwood’s or Fraser’s. Late in his life, during the furore

over parliamentary reform, Hogg’s reputation certainly suffered because,

unlike Burns, his poetry could not be pressed into service on the

popular side.

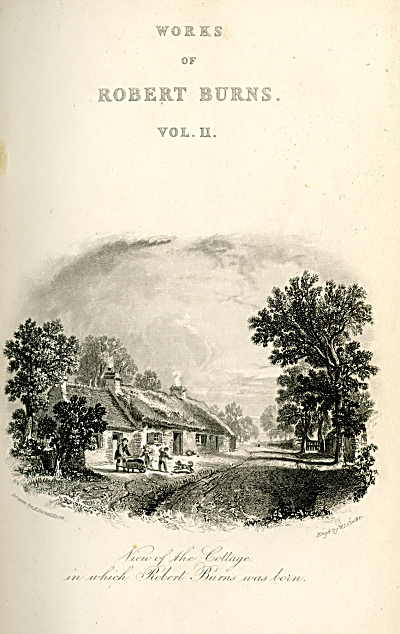

Thirdly, perhaps most important, publishing conditions had also

changed. Burns’s defining success had come quickly, from his Kilmarnock

volume, locally published by subscription, and it had come very much on

his own terms, at least initially. By contrast, Hogg’s career had to be

negotiated volume by volume through powerful Edinburgh publishers. His

first books were collections of songs, but by the eighteen-tens the

publishers wanted, not ballads or songs, but long narrative poems like

those of Walter Scott, Lord Byron, and Thomas Moore. By the late

eighteen-twenties the publishers claimed not to want poetry at all. In

spite of his strength as a song-writer and his satiric abilities, Hogg

found himself increasingly defined as a poet of bygone supernatural

legend. The pawky humour of some of his early ballads seemed dangerously

coarse to publishers in the age of Dr. Bowdler. And the same pressures

affected his treatment of religion. Although Hogg applauded Burns’s New

Licht satire on the unco’ guid, Hogg increasing wrote as the voice of a

devout Auld Licht tradition, and editors, mindful of the growing

middle-class evangelical market, pushed him in that direction. The

traditionalism, other-worldliness, and diffuse ambition of his own

poetic bent were reinforced by the pressures of a changed literary

market-place.

But to these historical factors in Hogg’s differences from Burns can be

added a difference of geography. In one of the most famous contemporary

comparisons of the two poets, John Wilson contrasted “the poetry of the

agricultural and that of the pastoral districts of Scotland.”

“Scotland,” Wilson asserted, “has better reason to be proud of her

peasant poets than any other country in the world,” but he argued that

their poetry varied with the area of Scotland each came from. In

Burns’s Ayrshire, for instance, the hard struggle of arable farming

encouraged a human, sociable, down-to-earth, this-worldly poetry, while

Burns’s descriptions of nature, Wilson asserted, were often derivative

and conventional; it was a good thing Burns was dead before the Romantic

fashion for “descriptive poetry,” else he might have been “seduced from

the fireside to the valley.” The isolated sheep-farming country of

Hogg’s Selkirkshire, by contrast, encouraged individuality,

other-worldliness, and a “wild enthusiasm towards external nature.” The

Burnsians who already, by 1819, “hold annual or triennial festivals in

honour of their great dead poet,” Wilson admonishes, should not “be cold

to the claims of the gifted living,” because “the genius of the two

poets is as different as their life.” Hogg naturally responded

positively to Wilson’s arguments about place and poetry--indeed, his

response was so positive that fifteen years later he included it pretty

much word for word, without acknowledgement, as chapter two in his own

memoir of Burns.

These varied factors--psychological, historical, and geographical--all

influenced Hogg’s development and self-definition as a writer. In

claiming poetic kinship with Burns, and in recognizing differences from

him, Hogg defined Burns as well as himself. The very strong admiration

at the core of this interrelationship is thrown into relief by Hogg's

more troubled relationship with a living contemporary, Walter Scott.

Scott was not only a fellow-borderer, near to Hogg in age, but Hogg’s

one-time patron, his social superior, and far and away more successful

in exploiting the expanding early nineteenth-century book-market. Indeed

Hogg blamed Scott for turning public taste away from poetry and towards

fiction; “I was obliged from the irresistible current that followed

him,” Hogg complained, “to forego the talent which God gave me at my

birth and enter into a new sphere with which I had no acquaintance.”

Hogg’s sometimes rather truculent struggle to assert equality with Scott

gives a clue to the significance Burns held for him and for his

reviewers. At first any such comparison was a matter of pride, yet Hogg

must soon have wearied of (in Wilson’s phrase) the “not uncommon”

contemporary assumption that “Burns had preoccupied the ground, and is

our only great poet of the people.” The Oxford Review might

describe Hogg rather loftily as “a poet of nature’s own creation, and

worthy to rank among the most distinguished of the Caledonian Bards;”

the long-established Scots Magazine might comment that “Mr. Hogg

seems at present to hold, in this country, the first rank among men of

self-taught genius.” But the subtext of the reviewers was always Hogg’s

belatedness.

As early as Hogg’s second volume The Mountain Bard (1807), the

Poetical Register commented that “the labouring class of society

has, of late years, teemed with poets and would-be poets,” while the

Annual Review snorted that “few classes of writer have, generally

speaking, less claim to originality that these self-taught

poets.” The London-based Critical Review, while painting Hogg as

“a literal sans-culotte” and purporting to be horrified at Hogg’s

“amorous familiarity,” nonetheless praised some of his 1807 poems as

“worthy of Burns, without copying him,” and lamented “England’s

inferiority” to Scotland in protecting “men of rising genius.” But even

in 1807, the Cabinet complained that “the rage for . . . obscure

bards,” on the model of “the Ayrshire Ploughman,” “is becoming almost

ridiculous,” and by 1811 the Critical Review had started to mock

“the now fashionable rage for rude simplicity” as “the very jacobinism

of taste and genius.” By 1814, even the Analectic Magazine of

Philadelphia commented that “it is nothing new, in these days, to hear

of shepherds and ploughmen writing poetry,” and pointed out the very

brief careers enjoyed by most poets of Hogg’s class “since Burns died.”

The constant undertow of Hogg’s reviewers was always the no-win

comparison with Burns. In that 1811 piece, the Critical Review

had commented that “it is very evident that Burns is the model of

imitation with most of these lyrical poets of the mountains,” and rather

backhandedly praised Hogg, even if he had “obligingly turned some of

Burns’s purest gold to his own use,” as being “not altogether void of

native genius,” and “more worthy to be compared with his original” than

other “geniusses of modern times.”

This anxious and often snobbish critical reaction against the sheer

multitude of Burns’s over-hyped would-be successors influenced the way

Hogg himself, and nineteenth century critics generally, came to view

Burns. Burns, they had to believe, was not only earlier than Robert

Bloomfield the farmer’s boy, Stephen Duck the thresher, Ann Yearsley the

dairy-maid, and so on; Burns was on a different poetic plane. The

others, wrote the Literary Review in 1815, were simply novelties:

Burns alone, like Shakespeare, received from

nature

powers which education could not have improved.

He

was one of the great original characters to whom

the

common rules of life are scarcely applicable…

To compare Burns with any of the other self-made

poets, who have nothing in common with him but

obscurity of birth,…would be to compare the

untamed

majesty of a stupendous range of Alpine scenery

with

the neglected barrenness of a heath or common.

W. H. Auden

famously wrote of his poetic precursor W. B. Yeats that “poetry survives

in the valley of its making,” and much modern biographical and

historical scholarship has labored to place Burns back in his original

context, but Burns’s importance to nineteenth-century readers lay

precisely in the way his poetry, especially his songs, continued to

speak outside that original context, across the years, beyond literary

or political fashion.

The specialness of Burns was just as important to Hogg himself. Burns

became the symbol to Hogg that a poet could rise above, not just humble

origins, but also financial vicissitudes and personal failings and

geographical isolation and political upheavals and even the difficulties

of the literary market-place. In attributing to Burns this kind of

timelessness, Hogg kept alive the hope that his own poetry too could

survive, could be distinctive, could overcome the frequent disdain of

modish contemporaries.

In mid-career, Hogg’s poetry had been very different from that of Burns;

during the eighteen-tens, he had churned out a whole series of

quasi-antiquarian supernatural poems, with diminishing effect. But in

his past decade or so, Hogg returned to shorter lyrical poems much

closer in style to those of Burns. For the title of one of his last

books he chose simply Songs of the Ettrick Shepherd. Hogg’s

poetic career had begun with song-writing, and some of even his earliest

efforts have a lilt to them:

Life is a weary, weary, weary,

Life is a weary cobble o’ care;

The poets mislead you,

Wha ca’ it a meadow,

For life is a puddle o’ perfect despair.

But of

course one doesn’t believe in the despairing sentiment of so upbeat and

bouncy a lament. In his later songs, like this resonant one about a poor

man asking for shelter written as Hogg himself was on the threshold of

old age, the tone can be much more personal and much more haunting:

Loose the yett an’ let me in,

Lady wi’ the glist’ning ee;

Dinna let your menial train

Drive an auld man out to dee.

Cauld rife is the winter ev’n,

See the rime hangs at my chin;

Lady, for the sake of Heav’n,

Loose the yett an’ let me in.

There is an

authentic Burnsian ring to a song like this, from the eighteen-twenties,

portraying the joys of rural love as “a secret that courtiers dinna ken:”

Awa’ wi’ fame and fortune, what comfort can they gie?

And a’ the arts that prey upon man’s life and

liberty:

Gie me the highest joy that the heart o’ man can frame,

My bonny, bonny lassie, when the kye comes hame,

When the kye comes hame, when the kye comes hame,

‘Tween the gloaming an’ the mirk, when the kye comes

hame.

And the echoes

of Burns’s influence in Hogg’s later poetry turn up again and again where

you might least expect them. I can well remember copying out and learning by

heart, at the age of seven or eight or thereabouts, a children’s song about

two boys playing in a country stream. It was one of the most

widely-anthologized of any of Hogg’s works:

Where the pools are bright and deep

Where the grey trout lies asleep

Up the river and over the lea

That’s the way for Billy and me.

It was only

recently that I recognized behind the central image of Hogg’s song the echo

from Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne” of a still-recoverable childhood friendliness

because “we twa ha’ paiddled i’ the burn.”

The

continuing impact of Robert Burns on Scottish poets of the next generation

like Hogg was both liberating and rather daunting. But in the reaction to

Burns both of Hogg himself and of his reviewers we can see, not only the

pervasiveness of Burns’s influence, but also the way the literary situation

and conflicts of the early nineteenth-century helped to shape the lasting

significance subsequent generations would find in Burns’s work:

The bards o’ our country, now sing as they may,

The best o’ their ditties but maks my heart wae,

For at the blithe strain there was ane beat them

a’,--

O there’s nae bard o’ nature sin’ Robin’s awa’!

POSTSCRIPT:

SOME BOOKS BY AND ABOUT JAMES HOGG

Hogg’s writings

are now much more available than they used to be, and much more is also now

known about his life. His best-known book The Private Memoirs and

Confessions of a Justified Sinner is in print in several paperback

editions. There have been several modern selections of from his writings,

notably Selected Poems of James Hogg, ed. Douglas Mack (Clarendon

Press, 1970), Selected Stories and Sketches, ed. Douglas Mack

(Scottish Academic Press, 1982), and Selected Poems and Songs, ed.

David Groves (Scottish Academic Press, 1986). A scholarly edition, The

Stirling/South Carolina Edition of the Collected Works of James Hogg

(Edinburgh University Press, 1995- ), also edited by Douglas Mack, has

published over twenty volumes so far, and is projected to reach nearly forty

volumes in all. There have been two recent biographies, very different but

both good: Karl Miller’s Electric Shepherd, A Likeness of James Hogg

(Faber, 2003) and Gillian Hughes’s James Hogg, A Life (Edinburgh

University Press, 2007), and Gillian Hughes has also edited Hogg’s

Collected Letters (3 vols., Edinburgh University Press, 2004-2007).

Finally, though this essay was first written independently of them, see

David Groves, “James Hogg on Robert Burns,” Burns Chronicle, 100

(1991), 51-59; Douglas S. Mack, “Hogg as Poet: A Successor to Burns?,” in

Love and Liberty: Robert Burns: A Bicentenary Celebration, ed. Kenneth

Simpson (Tuckwell, 1997), 119-127; and Kirsteen McCue, “Singing ‘more old

songs than ever ploughman could:’ the songs of James Hogg and Robert Burns

in the musical marketplace,” in Hogg and the Literary Marketplace,

ed. Sharon Alker and Holly Nelson (Ashgate, forthcoming). (PS: 6-10-08) |