|

Edited by Frank R.

Shaw, FSA Scot, Atlanta, GA,

jurascot@earthlink.net

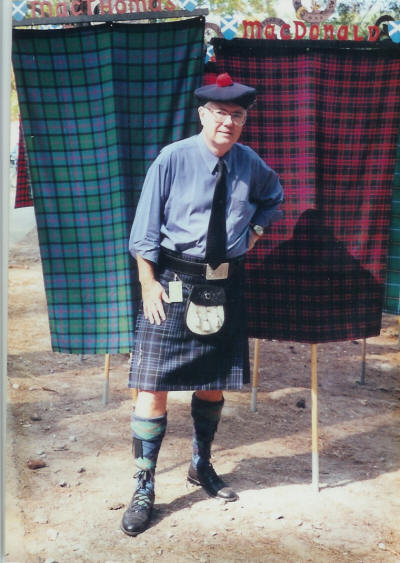

Stuart Leyden has held

pastorates in Rumson, New Jersey, Easton, Maryland, and Waukesha, Wisconsin.

For the last ten years, before retiring in 1989, Dr. Leyden did interim work

throughout America. His last church ministry was at the Roseville

Presbyterian Church, a 2,000 member church in Roseville, California. He is a

former adjunct instructor at the University of South Carolina at Beaufort,

where he taught “Introduction to the Bible as Literature and

Comparative Religion”. He currently serves as part-time pastor of

Trinity Presbyterian Church near the border of Cherokee and Forsyth counties

in Georgia. He and his wife Donna have ten grandchildren with another on

the way.

Dr. Leyden earned the above

degrees respectively from Wheaton College, Edinburgh University, Princeton

Theological Seminary, and Temple University.

Rev. Leyden says, “I have

two cousins in Glasgow, and more distant cousins on the Isle of Skye where

the MacDonalds live in peace with the MacLeods. But I do have a great

grandmother who was a Campbell. I attribute all the peculiarities of my

personality to that MacDonald-Campbell union!”

Our readers should find his

article interesting and thought provoking. The Church of Scotland’s

Life and Work asks, “Was the free-loving, hard-drinking Robert Burns

a moral reprobate with no interest in his immortal soul, or a man for whom

Christianity was a powerful influence?” Our guest writer, as you will see,

is quite capable of drawing his own conclusions.

WITH PASSIONS WILD AND

STRONG

By Stuart T. Leyden, B.A., B.D., M.Th., Ph.D.

When it comes to examining Robert Burn's

Christian commitment, opinion is hotly divided. Some contend that he was a

sceptic, a hostile critic of Christianity, and at best a "wistful agnostic",

[1]

but not a believing Christian. The other side embraces him within the faith

once delivered to the saints in the Calvinist expression of the Scottish

Kirk. Perhaps I should not proceed any further without warning the reader

that the evaluators often find in Burns whatever suits their prejudice. My

case is made as a first-generation American of Scottish ancestry, and as a

Presbyterian clergyman.

The case against Robert

Burns as a sincere Christian believer is made on several grounds. Firstly,

Burns seems much more interested in Satan or Beelzebub than God. In his

'Address of Beelzebub' he takes the part of the devil in advising the

privileged to deal harshly with the poor and disadvantaged:

The young dogs, swinge them to the labour,

Let WARK an' HUNGER mak them sober!

[2]

And in his 'Address to the Deil' he reminds us of the devil's

appearance in the Garden of Eden incognito (as a serpent) and of Satan's

power over Job. [3]

An' how ye gat him i' your thrall,

An' brak him out o' hous an' hal'

Secondly, Burns is held to be a critic of church life rather

than a supporter. One of his most famous and delightful poems, 'Holy

Willie's Prayer', is a scathing criticism of one of the tenets of the

hyper-Calvinism of his era, namely, the doctrine of double predestination

whereby the Al(FRS: 3-20-07)mighty with considerable delight consigns some

to heaven and some to hell. This theology is placed in the imaginary prayer

of a consummate hypocrite.

O thou that in the heavens does dwell!

What, as it pleases best thysel,

Sends ane to heaven an' ten to hell,

A' for thy glory

O Lord--yestreen--Thou kens-wi' Meg--

Thy pardon I sincerely beg!

[4]

In one shot Burns blasts the despotic fatalism of

the ultra-Calvinistic wing of the Kirk and exposes the sexual exploits of

hypocritical Willie.

Thirdly, Burns is a

self-confessed sceptic in matters of religion. He lived in the era of the

continental Enlightenment in which Voltaire in France, Tom Paine in America

and David Hume in Scotland raked Christianity over the hot coals of

rationalism-empiricism. In a letter to Cunningham he says, "I hate a man

who wishes to be a Deist, but I fear, every fair, unprejudiced Enquirer must

in some degree by a Sceptic." [5]

Lastly, his lifestyle was

that of a self-confessed rake who gloried in his sexual promiscuity without

regard for the consequences, namely, bastard offspring. To be fair, he and

his wife Jean did take one of them into their home. While flagrant sexual

laxity is not proof of disbelief, it does seem inconsistent with a Christian

lifestyle. In addition his interest in baudy sex found expression in his

collection of ribald songs in The Scots Musical

Museum.

At this point I am reminded

of Harry Truman's comment that he only wanted to talk to one-handed

economists. Economists, he said, always hedged their advice by saying, "On

the other hand…" As you would suspect there is another way to interpret

Burns' relationship to the Christian faith.

The fact that he wrote so

much about the Devil testifies to his knowledge of the Bible where that

unholy figure appears in the Garden of Eden and in the life of Job to tempt

and to test. One wonders if such a prominent symbol in his poetry might

suggest some inward struggles with temptation in Burns' own life.

Certainly, he was familiar with the teaching of the Bible on Adam's Fall and

the reality of evil in the world. Burns had fun with the Devil in more ways

than one, and he would not be the only believer who was more conscious of

evil than of grace. Moreover his compassion for the poor, and insistence on

human dignity ('A man's a man for a' that') may reflect not only his own

humble origins, or Enlightenment independence, but a grasp of the Biblical

teaching that humanity is made in the image of God.

Burn's criticism of Holy

Willie, the Unco Guid and all forms of religious self-righteousness put him

comfortably in the company of all the great prophets of the Bible and

especially in the camp of Jesus, who blasted the hypocrites over and over

again in the Gospels.

That he was a sceptic should

not surprise anyone. All sincere enquirers are bound to be sceptics,

doubters of God's goodness in a world where the innocent suffer. His

letters often fluctuate between belief and unbelief. He struggled. Late in

his brief life he wrote to a friend, Mrs. Dunlop, about his son Francis

Wallace and her godson: "I am so convinced that an unshaken faith in the

doctrines of Christianity is not only necessary by making us better men, but

by making us happier men, that I shall take every care that your little

godson, & every little creature that shall call me Father, shall be firmly

persuaded that

'God was in Christ,

reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing unto men their

trespasses'." [6]

A cynic might say that Burns

was simply trying to reassure a good Christian friend - telling Mrs. Dunlop

what she wanted to hear. But there are at least two reasons why I think

that kind of cynicism is unfair. When it was discovered that Jean Armour

was pregnant by Robert Burns, the Kirk Session disciplined them both, and

Burns appeared before the congregation. As far as I can discover he was not

coerced. In spite of that humiliation, he continued to attend worship in

his Kirk all his life: I assume repentant and forgiven.

Furthermore, Burns was

brought up on the Bible in his home and wrote two paraphrases of the Bible,

one on the first Psalm and another on 'Jeremiah 15th Ch. 10V'.

But familiarity with the Bible does not necessarily prove belief in its

teaching. There is one poem of Burns' that reveals profound Christian

belief. It is 'The Cotter's Saturday Night'. While it is true that you

cannot find anything else quite like it in any of his other poems, we must

not confuse quantity with quality. This poem has the quality of faith.

It is commonly assumed that

Burns is to some extent recreating a scene in his boyhood home where his

father, as priest in his own household, leads the family in worship. In

this poem Burns includes the sacred history of Abraham, Moses, alludes to

David on the lyre, Job's suffering, Isaiah's prophetic fire, the atonement

of Jesus' blood for the guilty, the triumph of God over Babylon in the book

of Revelation, the joy of family worship in the cottage and divine grace in

their hearts. If you find that this poem soars with the Spirit both

Christian and patriotic, perhaps it is because the author had a Christian

spirit as well as a love for his native soil. Listen to it:

The priest-like Father reads the sacred page…

Perhaps the Christian Volume is the theme,

How guiltless blood for guilty man

was shed;

How He, who bore in heaven the second name,

Had not on Earth whereon to lay his

head:

How his first followers and servants

sped;

…

Then kneeling down to Heaven's Eternal King

The Saint, the Father, and the

Husband prays

Hope 'springs

exulting on triumphant wing' [7]

Perhaps in a more profound way than many of his

ecclesiastical contemporaries, Robert Burns understood human failing and

Christian redemption. If his self-confessed doubt eliminates him from the

Christian fold, who then can claim "Grace divine"? (FRS: 3-20-2007)

|