|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

This is an article promised and

delivered to me some months back and I must confess that it became lost in the

hundreds of emails I have on my computer. If I told you this was the first time

I have lost an email, I would not be telling the truth. But if I told you this

was the first time I had lost an important email meant for the pages of

Robert Burns Lives!, I would be telling the truth. Usually my articles come

in one at a time or, on rare occasions, maybe two will show up close together

for publication. I received this one along with four other articles over a

period of a week, an experience I have never encountered since beginning the

Burns study many years ago! Please forgive me, Patrick Scott, for this huge

error on my part. What I found hard to do was accept that I had misplaced the

writings of a great Burns scholar like Patrick and, being the gentleman he is,

he waited a long time to contact me to see if there was something he could do to

improve the article for it to qualify for RBL! It really bothers me to know

Professor Scott had worked the hours he did on the article only to have me lose

it until he reminded me. This mistake on my part really stung and still does.

To correct this happening again,

I have set up a ticker file for Susan to keep track of knowing she reported

directly to four different Chairmen at The Coca-Cola Company while working there

35 years. That will assure that I am in good hands and will not make this same

blunder in the future. Plus, if it did happen again, it gives me an out with

someone else to blame if I have the nerve to do so!

This is Christmas week and I

want all of us “to enjoy the Magic of the Season”, a small phrase I learned this

week from the pen of Lisa Wrightenberry, Executive Assistant to Tom McNally,

Dean of Libraries at the University of South Carolina. So enjoy Patrick’s

article below as it is most unusual as is the season we now celebrate. Burns’

Kilmarnock is one of the most important books in Scottish history. (FRS:

12.24.15)

Tracking the Kilmarnock Burns:

Allan Young’s Census and the Hunt for “Lost” Copies

By

Patrick Scott

When the “Kilmarnock Burns,”

more formally Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect by Robert Burns, was

first printed in 1786 in John Wilson’s shop in Star Inn Close, Kilmarnock,

Wilson printed only 612 copies. It was a thin paper-wrappered volume, eagerly

read by its first readers, but also easily damaged, and soon to be superseded by

the more substantial collection published in Edinburgh the following spring,

with a stronger but still temporary cover of paper-covered boards.

Some fifteen years ago, Allan

Young, a Scot living in Florida, decided to find out for himself just how many

of those 612 copies still survive, and where they are. He tracked down some 74

of them, mostly in libraries or universities, together with a handful still

owned by individuals. He also calculated the chances that other copies, once

known to Burnsians or the book trade, but now untraceable, would have survived,

estimating that there might be another ten to twenty copies hidden away that he

had not been able to find. His project aroused considerable interest. He

presented his findings at the Burns at 250 conference in South Carolina in 2009,

and he published a summary of his research in the Burns Chronicle (Young,

2011). Although his draft census or list of owners has never been

publicly distributed, it has been cited by a Scottish auction house as the most

authoritative research on the subject (Young, 2009: Lyon and Turnbull, May 12,

2012, lot 72).

I had met Mr. Young several

times during his research, not just at the 2009 conference, but before that

when he came up to South Carolina, to use the G. Ross Roy Collection and to

discuss his project with Ross Roy. I knew that many people remained interested

in his Census, though he had set it aside awaiting some additional research than

he was not then able to undertake. This past spring I summoned my courage,

phoned him up, and asked if he would consider letting me assist him in getting

it into shape for formal publication. To my delight (and relief), he said yes,

and in July, once we were both through some traveling, we began in earnest to

review what still needed to be done.

Since then, we’ve had some

discoveries, most of which must wait till the Young Census is actually

published, but his earlier research holds up remarkably well, and while there

are a few additional copies we do not anticipate the total number of known

copies will edge up much further. This past month, Mr. Young has been back in

Scotland and has been able to examine a number of copies in detail for which

there had been record or no full description. We would of course be very

pleased to get into contact with any additional Kilmarnock owners or libraries

with Kilmarnock editions which whom we have not yet been in contact.

Where we have been able to

expand most on the original Young census, however, is in the survey of

previously-recorded copies and in matching more of them to the copies that are

now known. This has involved searching through over a hundred years of auction

records, and some 200 years of newspapers. These records often include

information under one or more of these headings:

1. Previous owners: Some

copies have inscriptions or bookplates that give a good record of earlier

ownership.

2. Binding: For other

copies, the binding may give a good clue: because the Kilmarnock edition was

originally issued in papers wrappers, almost all the surviving copies have been

rebound at some point over the past two centuries, either soon after publication

as protection, in plain calf, or with a calf spine and marbled boards, or later

on to upgrade a worn copy, often in a fine morocco binding, elaborately

gilt-decorated, marked with the name of a recognized binder such as Bedford,

Rivière, or Zaehnsdorf.

3. Size: The original

paper-wrappered copies were left with the edges rough (“uncut” or “untrimmed”),

but when a copy was bound or rebound the edges would be trimmed to be even;

early nineteenth-century binders would often color or marble the trimmed edges,

or at least the top edge, while copies in fine bindings usually have “all edges

gilt” (“a.e.g.” in the catalogues). Every genuine Kilmarnock is a rarity to be

treasured, but collectors have traditionally prized “tall copies,” those that

have lost the least in trimming. In the 1890s the great Burns collector William

Craibe Angus published a table setting the price a collector could expect to pay

for a copy of each height from the tallest, over nine inches, then worth up to

£200, to the smallest, around seven inches, worth about £30 (Craibe Angus, 1893)

4. Missing pages or other

damage: Lastly, because the original binding was flimsy and temporary, many

copies got damaged, and lost some pages, perhaps losing the iconic Kilmarnock

title-page or part of the glossary in the final pages. In auction terms, these

copies were said to be “imperfect,” and when a copy was rebound these pages

would often be replaced so the book once again seemed complete. Sometimes the

replacement would be from one of the M’Kie facsimiles, sometimes (esp. for

missing title-pages) from a specially-made photolithographic facsimile, and

sometimes a leaf or leaves cannibalized out of another damaged copy. Quite

beautifully rebound copies, described in the sale record as “morocco, extra,

gilt, a.e.g,, a tall copy,” may in fact have a damaged textblock that has been

cunningly “made up” in this way.

No two surviving copies of the

Kilmarnock are going to be exactly alike. When auction and dealer

catalogues describe a Kilmarnock, they usually include page measurements, and

responsible catalogers make a detailed record of any pages that are missing or

damaged or that have been replaced with facsimiles. No two copies are likely to

have exactly the same combination of ownership evidence, binding, decoration,

page-size, and earlier damage or repair. The combination of such markers serves

to identify individual copies, helping to match up the older records with copies

that are now known, and so piece together the history of each copy. The same

markers, of course, when they fit a copy that was well-described forty or eighty

or a hundred years ago but don’t match up with any copy in the main census list,

help identify which previously-recorded copies might still be out there with an

untraced owner at an as-yet-unknown location.

For some

copies, the history comes together in one unbroken sequence. One of the most

famous Kilmarnocks is now at Harvard. In 1857, Dr. William Burns, who started

life as a handloom weaver in Forfar, worked his way through college in Aberdeen

to become a mathematician, and settled as a schoolmaster in Rochester, south of

London, came on a copy in wrappers in “a parcel of old books” which he had

bought “for a trifle” in an auctioneer’s office (F.H., “The Dundee Copy”). The

books came from a Glasgow family named Drummond. In 1870, his home town was

raising funds for a Free Public Library, and Dr. Burns donated his Kilmarnock to

be sold for the library’s benefit; an energetic local newspaper editor

publicized the sale, and it was bought by a local collector, a Mr. G.B. Simpson

of Broughty Ferry, just outside Dundee, who paid 6 guineas (then about $32).

Just nine years later, Mr. Simpson sold the copy, by now preserved in a leather

case, with four other Burns items, to Mr. A.C. Lamb of Dundee, who apportioned

£100 [$500] of the total purchase price to the Kilmarnock (F. H.; and cf. also

Craibe Angus). In the Burns centenary year 1896, it was Mr. Lamb who displayed

the copy “in the original paper covers as issued” in the great Glasgow

exhibition (Memorial Catalogue, p. 459, Lamb item 10).

Following

Mr. Lamb’s death, the copy was auctioned at Dowell’s Rooms, Edinburgh, February

7, 1898, for 545 guineas (572.25

or about $2750: a “fabulous sum,” for “quite the most important lot”), and was

purchased “after a very keen competition” and “an exciting contest” by Mr.

Sabin. The annual record of auction sales commented: “Without doubt the finest

copy that has been sold by auction since the commencement of BOOK-PRICES CURRENT

in1887. The price realised is the highest so far obtained for any copy of this

extremely scarce work” (Book Prices Current, 12 [1898], p. BR114). That

1898 sale was a harbinger of things to come: Mr. Sabin was a London dealer, who

sold it onto an American dealer. The copy’s next private owner was a New York

collector, Mr. Caulfield, and in due time, in 1911 or 1912, it was an American

dealer, Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach who sold “the Lamb copy” to the young Harvard

graduate Harry Elkins Widener, of Philadelphia, for $6000. In 1912, Harry

Widener, coming home from a book-buying trip in London, went down with Titanic,

and his book collection was given to Harvard, to become the centrepiece of the

library that bears his name (Rosenbach, vol. I, p. 87). There it has stayed.

What is significant about the

story of the Lamb copy (the Burns-Simpson-Lamb-Caulfield-Widener-Harvard copy)

is not just the very steep upward curve in price, reflecting both a new

internationalism in the rare book trade and a new awareness among of collectors

of the vaue and rarity of copies in original condition. Between the Edinburgh

sale in 1898 and its purchase by Harry Widener three other copies with wrappers

had made headlines: the copy owned by G. S. Veitch of Paisley, bought after

direct negotiation by the Trustees of the Burns Cottage in 1903 for £1000 (still

in Alloway); the copy owned by William Van Antwerp of New York, sold at

Sotheby’s in 1907 for £700 (since 1940, in the Berg Collection at the New York

Public Library); and and the copy from Robert Hoe’s library, in a fine binding,

but uncut and with the wrappers bound in at the end of the volume, sold in New

York in 1911 for a record $5800 (since 1950, in the National Library of

Scotland).

In other cases, even for copies

with a significant provenance or important additional material, the trail can

run for many years, and then run into a dead end. An example is the copy that

once belonged to Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Glencairn (1725-1801), so with

an intermittent provenance going back to the book’s original publication, and

with her inscription on the title-page recording that Burns had presented it to

her n or shortly before December 6, 1786, soon after he went to Edinburgh (Roy,

Letters, I: 69, 71, 72). In the mid-19th century it was owned

by the Scottish antiquary and collector Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe (1781-1851),

whose father had known Burns in the Dumfries years. On Sharpe’s death, his

collections were sold at auction (the two sales together lasted a full two

weeks), and the Kilmarnock was bought by the bookseller William Pickering, who

sold in 1856 sold it for £5 to Burns’s nephew Gilbert Burns (1803-1881), of

Knockmaroon, County Dublin (Gibson, 1881, pp. 272, 299). Gilbert’s wife Jemima

long outlived her husband, and it was she who loaned the copy for the Glasgow

exhibition in 1896 (Memorial Catalogue, p. 53, item 314). Their eldest

son Robert Burns (1847-1901) predeceased Jemima, and it was not till 1921 that a

grandson, Kenneth Glencairn Burns, offered quite a large group (35 items) of

Burns material from Knockmaroon for sale, initially as a single lot with a

reserve of £10,000 (Burns Chronicle, 1921, pp. 163-164).

There were clearly no takers for

the collecton as a whole, and the Lady Glencairn Kilmarnock was auctioned at

Sotheby’s in July, fetching £810, and being bought by Sabin, the same London

dealer who bought the Lamb copy (Book-Auction Records, 18, 1921, p. 645).

We do not yet have any information on its whereabouts or ownership for the next

seventy years, when it again came to auction, when the library of the American

collector H. Bradley Martin was auctioned at Sotheby’s, New York. On April 30,

1990, the Glencairn/H. Bradley Martin copy fetched $36,000 hammer price (or

$39,600 with buyer’s premium; over $75,000 at current value). The detailed

description in Sotheby’s catalogue confirms the earlier provenance, noting also

that inserted in the book was the 1856 sales invoice from Pickering to Gilbert

Burn (Library of H. Bradley Martin, vol. 8, lot 2680; American

Book-Prices Current, 96 (1990), p. 409). Auction records no longer identify

buyers, and auction houses, like book dealers, do not disclose a buyer’s

identity either. A copy like this, in good condition with a great provenance,

and recently sold for a very substantial price, is not really lost; it will be

safe enough with its next private owners; but there does not seem to be at

present any public record of its location.

A third example has a happier

ending, where the earlier records on a “lost” copy of the Kilmarnock helped

solve a puzzle about a copy that a library had recently bought without the

seller having much information about it. Among the copies displayed in 1896 was

an imperfect or fragmentary Kilmarnock, “Mrs. Provost Whigham’s copy,” which

inscribed in a later hand as presented by Burns to Edward Whigham, innkeeper and

later provost of Sanquhar, and his wife. The copy included a transcription also

of the verses “At Whigham’s Inn,” which have commonly been accepted as written

by Burns (cf. Kinsley, I: 459). At that time the copy was owned by Mr. James R.

Wilson, of the Royal Bank, Sanquhar, and the verses, said to have been etched by

Burns on a window at the inn, had recently been printed in a recent Burns

Chronicle (Hewat, p. 93). The copy, by then owned by a Mr. Douglas Crichton

of Sanquhar, was auctioned at Sotheby’s in London in July 1910, when it was

bought for £26 10s., by Hornstein, the London dealer who would later cause

outrage by sending the Glenriddell Manuscripts to the U.S., before they were

repatriated to Scotland by the Philadelphia collector John Gribbell (Book-Auction

Records, 7, 1910, p. 509). Thereafter, there followed a hundred years with

no information about the copy’s whereabouts. The inscriptions and verses in the

copy were not in Burns’s hand, and the copy itself had many missing leaves,

including the title-page; it was just the kind of copy at some point might well

have been thrown out after the owner died or when a house had to be cleared in a

hurry.

However, about two months ago, I

was checking the Princeton University Library web-site for further details on

the much better Kilmarnock that Mr. Young had already listed from previous

research, when I noticed another, brief, non-standard catalogue entry that

seemed to suggest Princeton had a second copy. It turned out to be an

acquisition record for an imperfect copy they had recently bought locally but

had held off cataloguing till they could find out more about it. One of the

Princeton rare books staff, Jennifer Meyer, kindly sent us a detailed

description, and photographs, and it turned out to be Mrs. Provost Whigham’s

copy.

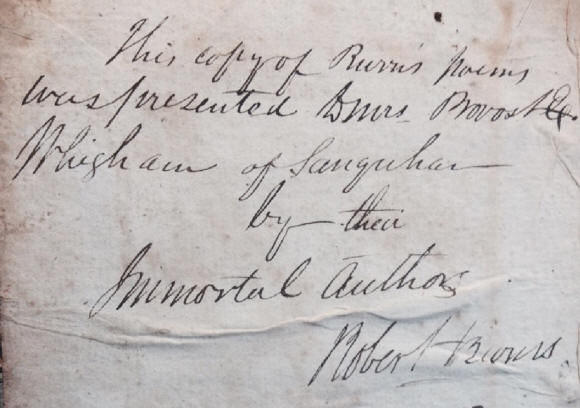

Inscription (not in Burns’s

hand) from “Mrs. Provost Whigham’s Kilmarnock”

(Image courtesy of Rare

Books, Princeton University Library).

Though I later discovered that

the verses were not in fact originally by Burns, the copy almost certainly had

descended in the Whigham family. We had tied up a loose end by locating a

missing but previously-recorded copy; Princeton have much fuller information

about their recent purchase; and the Glasgow team working on the new Burns

edition have better information than any previous editors about “At Whigham’s

Inn.” (For a full account of this copy, see also Scott, Burns Chronicle for

2016, forthcoming).

In an article in the Burns

Chronicle in 2011, Allan Young posed the question about these lost and

missing copies: “Where are they all now?” We can’t realistically hope to track

down all the copies that have previously been recorded; as Mr. Young tells me,

the census will be a snapshot of the information available to us at this time.

But gradually we are matching some of the known copies against these earlier

records and shrinking the pool of unlocated or missing copies. We would be very

pleased to hear from Kilmarnock owners with whom we have not yet been in

contact, and from any Burnsians, librarians, or others who might point us to

further survivors.

References

William Craibe Angus,, “Notes on

the First and Early Editions,” Burns Chronicle, 1st ser., 2 (1893),

83-95.

James Gibson, Bibliography of

Robert Burns (Kilmarnock: James M’Kie, 1881).

“F.H.,” “The Dundee Copy of the

First Edition,” Burns Chronicle, 1st ser., 8 (1899), 86-90.

Kirkwood Hewat, “Burns and Upper

Nithsdale,” Burns Chronicle, 1st ser., 5 (1896), pp. 86-97 (p. 93).

James Kinsley, ed., The Poems

and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

Lyon and Turnbull, Edinburgh,

May 12, 2012, sale 346, lot 72, catalogue online at::

http://auctions.lyonandturnbull.com/auction-lot-detail/346/72

Memorial Catalogue of the

Burns Exhibition ... Glasgow, 1896

(Glasgow: William Hodge, 1898).

A.S.W. Rosenbach, A Catalogue of the Books and

Manuscripts of Harry Elkins Widener, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: privately

printed, 1918).

G. Ross Roy, ed., The Letters

of Robert Burns, 2nd ed., revised, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985).

Patrick Scott, “‘At Whigham’s

Inn’: Mrs. Provost Whigham’s Lost Kilmarnock, the Allan Young Census, and an

Unexpected Discovery,” Burns Chronicle for 2016 (forthcoming).

Sotheby’s, The Library of H.

Bradley Martin, 9 vols (New York: Sotheby's, 1989-1990).

Allan Young, An Enquiry into

the Locations of the Extant Copies of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, by

Robert Burns, Printed by John Wilson, Kilmarnock, 1786 (The Kilmarnock Edition)

(Drafts: December 2003; revised, September 2008; revised, March 2009).

__________, List of Owners of

Known Extant Copies

(July, 2009).

__________, “612 ‘Kilmarnock’

Editions: Where are they all now?,” Burns Chronicle (Summer, 2011), pp.

4-5. |