|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Dr. Clark McGinn having just received his PhD

from the University of Glasgow.

One of the best supporters of Robert Burns

Lives! is Clark McGinn who, in the coming months, will be presenting the

remaining six of his nine articles featuring the men who first gathered back

in 1801 to honor Burns. The first article introduced us to The Reverend

Hamilton Paul who was responsible for the annual Burns Night Suppers we

celebrate every January. You can read Clark’s account entitled A

Forgotten Hero in Chapter 141 from our index. The good Reverend’s

contribution was truly a gift that keeps on giving. In Chapter 190, you

will find Clark’s second piece pertaining to a friend of George Washington’s

by the name of Primrose Kennedy, and today’s piece is on Provost John

Ballantine and will be Chapter 204. If plans go forward as envisioned, the

fourth article will hopefully be on your computers around the last of August

or the first of September. Clark has completed, defended, and was awarded

his PhD from the University of Glasgow a couple of weeks ago. He is Managing

Director of CHC Helicopter Leasing (Ireland) Limited and, interestingly, was

not a fulltime student at the university during his studies. Welcome back,

Dr. McGinn, and congratulations on your outstanding accomplishment. (FRS:

7.17.14)

THE FIRST NINE GUESTS: NUMBER THREE: ‘PROVOST

JOHN’

By Clark McGinn

In a way, I met John Ballantine before I really

met Robert Burns. When I was at secondary (high) school at Ayr Academy, the

Rector (headmaster) had from time to time requested the pleasure of my

company in the sanctum sanctorum of his office. Fortunately I cannot

recall the incidents, omissions or demerits on my part which occasioned my

personal acquaintance with William Reid MA and as I recall I left with no

marks of the physical retribution that was still a part of the rough and

tumble of the Scots education system in those days. What I do remember was

seeing a luminous portrait behind ‘Happy’ Reid’s head – in an unmistakable

style that I now know and love as Raeburn – of an older gentleman from the

great age of Scotland’s Enlightenment period , benevolent of face wistful of

mien. Our school is fiercely proud to be the oldest independent school in

Scotland (founded prior to AD 1233) and was reconstituted and re-named under

Royal Charter in 1796 and the Rector told me that this portrait was the man

behind that plan, a friend and patron of Robert Burns. Let me tell you about

him today: Provost John Ballantine of Castlehill.

Portrait of John Ballantine, Esq. Of Castlehill,

by Sir Henry Raeburn [1]

John Ballantine was born on in Ayr on 22 July

1743 into a very successful and wealthy family in the burgh. His ancestors

had served as provost (which is how we Scots describe the mayor of a town)

in what was in those days as prosperous a town as its near neighbour,

Glasgow. The Ballantines (who seem to have adopted a relatively cavalier

approach in spelling their surname) built up interests trading through the

port of Ayr most notably to the Scots settlements in Virginia and the

Caribbean. Not all were successful and the family estate of Castlehill just

out of the town had to be sold a century or more before John’s birth and the

family re-based themselves in a house within the town boundaries. John’s

grandfather Provost John Ballantine (1st) maintained the family

dignity in the royal burgh and his eldest son William (John’s father) worked

hard not only to maintain the family status, through family links with the

other powerful families in the burgh and the county, but more importantly to

rebuild the family’s finances and served the burgh as Dean of Guild. Of

eight children born to him and his wife, only three boys survived infancy.

William Junior, Patrick and the subject of this memoir, John.

Young William died aged 38, and his brother

Patrick went out to Virginia to venture with a group of Ballantine cousins

while John stayed in Ayr to manage the inbound trade. The brothers had been

admitted as ‘burgesses and guild brethren’ of the burgh which brought them

within the monopolies controlled by the town. The tobacco boom made a great

many fortunes in Scotland, but the scale of the trade meant that by the

1760s bigger ships funded by greater capital from Glasgow used the better,

deeper harbours of Greenock and Port Glasgow as the ventures grew to an

industrial scale. The merchants of Ayr, the Hunters, Fergussons and

Ballantines could not compete with this huge capacity and so they looked for

a new trade and so they looked for a commodity elsewhere in the Western

American seaboard which had high demand and high profit. They decided to

sell out of their tobacco interests, leaving the Virginian Ballantines to do

business with the Glasgow ‘Tobacco Lords’ while Patrick Ballantine set sail

for Jamaica to trade in sugar.

In fact, this was to turn out to be fortuitous,

as the American War of Independence hit the economy of the West of Scotland

hard, and the town of Ayr in particular. The Virginian cousins played

political possum, releasing Patrick and adhering to the new Revolutionary

constitution, which allowed them to keep their interests even though they

were hard hit too by the cessation of shipments to their old customers. The

Ayr merchants who had sold out ensured that not all their eggs were in one

basket, and so did rather better. So by exiting tobacco, the port of Ayr

maintained a diverse and for a long time viable trade. For the next couple

of decades, until the deep water ports around Glasgow became the imperial

entrepôt and ‘second city of the empire’, around three hundred ships a year

delivered produce to Ayr’s merchants well in excess of cargoes of sugar and

a bit of tobacco: tons of salt came from Spain, thousands of tuns of wine

from Spain and France, crates of earthenware from the English potteries and

roof upon roof of the slate from the Western Highlands needed to

weatherproof the architectural developments happening across Scotland. The

external trade grew through the despatch of coal from Ayrshire’s black

hinterlands to Ireland.

A very significant proportion of that prosperity

accrued to the old merchant families. In 1770, two brothers, James and

Robert Hunter built a seven story sugar refinery beside the harbour in Ayr

to capitalise on the West Indian shipments. James was cashier of the fast

growing ‘Ayr Bank’ whose Sunday name was Messrs Douglas, Heron & Company.

This banking partnership was the RBS of its day, both in rapid growth, in

dominance of the lending market and its spectacular implosion. This was a

major blow to the Ayrshire economy as most of the local landlords had

invested in (and borrowed from!) the Ayr Bank and, under the laws of the

time were therefore liable for a proportion of its debts. Some estimates say

that nearly two thirds of Ayrshire estates changed hands as a direct

consequence of this early financial debacle as the old gentry had literally

to sell the family silver to avoid ruin. Merchant families such as the

Hunters, the Hamiltons and the Ballantines were poised to do well.

James Hunter had managed to escape the wreck of

his bank, being only an employee not a shareholder and he recognised the

need for a new bank to finance the town’s trade albeit a more prudent one.

Messrs. Hunter & Co opened its doors in 1773 with James Hunter and his

cousin and namesake James Hunter of Edinburgh being the prime movers, with

the latter (who would become Sir James Hunter Blair, Bart), being also in

partnership with the leading Edinburgh banking house of Sir William Forbes &

Company. The cousins, plus a brother each and a son-in-law invested a

staggering £10,000 (around US$ 4.5 million today) and adopted a cautious

policy of financing sound merchants. James Hunter of Ayr died in 1776 and,

having garnered good profits from the Jamaica trade his wife’s cousin John

Ballantine bought his leading share in the bank.

Royal Burghs in those days were a tangled web of

monopoly trade privileges and a closed political oligopoly. Trade within

the burgh was regulated and only bone fide inhabitants who has become

‘burgesses’ could buy and sell commodity goods. Similarly the nine key

trades were all incorporated by Royal Charter under a Convener and Court and

no-one could set up business within the burgh unless he had joined that

trade body (either through birth, apprenticeship or buy buying in at a

premium). They acted like a combination of a trades union and a life

assurance policy and ranged from the Squaremen (masons and building trades)

and Hammermen (metal workers) to the Tailors (who had ancient rights to

process through the town in fancy dress on St Crispin’s Day), Shoemakers,

Coopers, Weavers, Skinners, Dyers and Fleshers (or butchers). The final

piece of the economic jigsaw was the ‘guild brethern’ or Merchants’ Company

headed by the Dean of Guild who held the monopoly of buying and selling

foreign goods. The burgh was managed by a town council which consisted of

the Provost, supported by two Bailies (aldermen) and the Dean of Guild

(representing the merchants) and the Deacon Convenor (one of the trades

convenors elected by his fellows) plus twelve councillors. The burgesses had

no vote as on the annual Election Day which was held on Michaelmas (29

September), the outgoing council elected its own replacement, in a cosy

self-perpetuating oligarchy.

John Ballantine obtained election as one of the

merchant councillors in the closed election process of the Ayr Town Council,

becoming Dean of Guild in fairly short order and latterly Provost in 1787

(following his relative James Fergusson) and then regularly thereafter in

1788, and 1793/94 and finally 1796/97. In a time of at least slothfulness

and typically gross corruption in burgh politics, Ballantine was widely seen

as a modernist, if not a political reformer with an unusually honest and

open approach.

While it is possible to exaggerate this – John

Ballantine was no democratic reformer but believed in using the existing

levers of power in a benign and beneficial fashion within the broadly

Whiggish world he loved. In the last article about Captain Primrose Kennedy,

we talked about the pre Reform Act elections to the UK House of Commons for

county seats like Ayrshire where the vote was limited to landowners of a

stipulated wealth. The elections for burgh seats in Scotland made that look

like cutting edge democracy. In those days, small groups of Scottish Burghs

were grouped together to send an MP to Westminster. Election was not by the

residents, however, but by each town council meeting in closed session to

decided who it wanted (often under pressure from the local grandees) and

then five delegates (one from each burgh) sat down together on election day

as an electoral college and those five votes decided the election.

Ayr was always pretty independent (or

bloody-minded) and typically traded off the power, threats and promises of

four great Earls, the Glencairns (in decline); the Kennedys (holding fast);

and the Eglintons (growing in influence) with the Loudons (part of the

nationally powerful Campbell faction, but headed in Ayrshire by a baby

girl). The tensions – and fundamental honesty of Provost John – can be seen

in an anecdote recounted by Hamilton Paul to the great antiquarian Robert

Chambers. A parliamentary election fell to be held in one of John

Ballantine’s years as Provost. Ayr and one other burgh favoured Ballantine

but it was known that the other three were in the pocket of the mighty Duke

of Argyll, the head of the Campbell faction. On Election Day, only four men

were present at the Burgh cambers in Ayr as storms had prevented the

delegate from the Campbell capital of Campbeltown from arriving. The vote

was tied at two for Ballantine and two for Argyll’s candidate so under

election law, Provost John had a casting vote and he amazed the political

world by giving it for Argyll, as he would not take the nomination on a

technicality. (On the other hand, making an enemy like Argyll was bad for

business both as a merchant and a banker, so maybe there was more practical

wisdom in the decision than not.)

His enduring contribution to the town was his

instrumentality behind two major capital projects which still exist today:

the building of the original ‘New Bridge’ of Ayr and the piloting of the

Royal Charter to turn the ancient Burgh or Grammar School into Ayr Academy.

The river Ayr had only one bridge in the late

1700s, the famed ‘Auld Brig’ of Ayr, which was a mediaeval construction

built through the bequest of two spinster sisters and which remains one of

the oldest functioning bridges in Scotland today. It can only bear the

weight of pedestrians nowadays, and it was not much better in Ballantine’s

time when lumps of ancient sandstone would regularly fall off into the river

below, and it was recorded that the structure shook violently if two

wheelbarrows passed at the same time. It was Ballantine who saw the need to

have a new bridge linking the town to the road to Glasgow and as the Dean of

Guild was responsible for building permits within the burgh, he journeyed to

London to lobby Westminster for a private Act of Parliament that would allow

the burgh to borrow £5,000 to fund the construction of a bridge and to

charge a toll for each crossing to repay the debt without endangering the

town’s credit. (There is, literally, nothing new under the sun).

Parliamentary approval came through in 1785 and

Ballantine rushed home with a set of plans anecdotally drafted by the

greatest Scots architect of the day, Robert Adam, but whether Mr Adam’s fees

were too high or his attentions were elsewhere, the New Bridge was actually

built by a local stone mason, called Alexander Steven, between 1786 and

1788. Around the same period, Ballantine and his colleagues took steps to

improve the general streets of Ayr, and in converting the Hunters’ Sugar

House into a new barracks, albeit by diverting monies from the Bridge Fund

not quite within the meaning of the Act (old habits die hard). To mark the

event, and to thank his patron, Robert Burns took inspiration from Robert

Fergusson's poem Mutual Complaint of Plainstanes and Causey' for his own

'The Brigs of Ayr', which was dedicated to John Ballantine in the Edinburgh

Edition of 1787. Here the spirits of the curmudgeonly ‘gothick’ Auld Brig

and the fashionable New Bridge squabble.

Auld Brig appear'd of ancient Pictish race,

The vera wrinkles Gothic in his face;

He seem'd as he wi' Time had warstl'd lang,

Yet, teughly doure, he bade an unco bang.

New Brig was buskit in a braw new coat,

That he, at Lon'on, frae ane Adams got;

In's hand five taper staves as smooth's a bead,

Wi' virls an' whirlygigums at the head.

The poem is doubly famous for what turns out to

be some form of prophesy. The auld Brig admonishes his new rival:

'Conceited gowk! puff'd up wi' windy pride!

This monie a year I've stood the flood and tide;

And tho' wi' crazy eild I'm sair forfairn,

I'll be a brig when ye're a shapeless cairn! '

And true enough, a weakness in the design or

execution caused the New Bridge to collapse in the major floods of 1879,

just lasting a century before needing to be completely rebuilt. The New New

Bridge still stands safely across the Ayr today. While it might seem odd to

the casual reader that Burns rewarded his patron with this dire warning as

to his architectural legacy, the end of the poem sees the coming together of

the spirits of the River Ayr and its tributaries, each representing a core

value of the Scottish Enlightenment, of whom John Ballantine may be

considered the embodiment in the town of Ayr.

His second project, which needed another Act of

Parliament was creating Ayr Academy where he served as the first Chairman of

the Board. As mentioned the town of Ayr has an ancient history of educating

its youth. One of the Fergusson clan, James Fergusson of Doonholm made a

colossal fortune in India and at his death left a substantial £1,000 to

further improve the town’s school. Ballantine again swung into action in

his second Provost-ship. As the well-known Ayr historian (and himself an

Academy teacher), John Strawhorn described the Enlightenment project:

Proposals issued in 1794 pointed out the

advantage of ‘a good Education.’ Study at Universities could be ‘tedious and

expensive ‘’’ (producing) speculative and indolent habits ... ill-suited to

the circumstances of the great bulk of the people in a commercial country.

But a local academy would offer ‘the most necessary and useful parts of

learning ... under the observation of their parents and friends ...

furnished with teachers of approved ability.’

Of over two hundred subscriptions, around a third came from Ayr men made

good in the East or West Indies. King George signed a Royal Charter in 1798

and the old Burgh School, like the river crossings of Ayr, joined the modern

world.

Provost John was not just a businessman and

reformer, he had time for the pursuits of leisure. He was a practising

Freemason, and served as Master of Ayr Kilwinning Lodge. With his friend

and former business partner Hugh Hamilton of Pinmore, he renewed interest in

the Ayr racecourse (the ‘old racecourse grounds which sit beside Hamilton’s

beautiful Belleisle estate) founding the prestigious Ayr Gold Cup in 1804

(which is still the most important flat horse race in Scotland) and

regularly hosting the Caledonian Hunt amongst others. He was a natural ‘New

Licht’ in religion, being related by marriage to William Dalrymple of Ayr

Auld Kirk and David Shaw of Coylton (who was Hamilton Paul’s mentor while

still an active parish minister in his 90s). Provost John’s liberal views

were well illustrated in his weekly dining club called ‘The Sunday School’

which met each Sunday after Church to eat, drink and debate in a convivial

atmosphere albeit in contradiction of the Fourth Commandment.

On the day that the young Hamilton Paul boarded

the mail coach to take him from Ayr to start his studies at Glasgow

University, he shared the inside seats with John Ballantine and one of his

sisters (neither John nor Patrick ever married) but was too abashed by being

in close proximity to the greatest man in the burgh that for the first and

last time in the Reverend’s life, he was at a loss for words. He made up for

it though, after 1801, the Provost included Hamilton Paul amongst his old

acquaintances around both the board of the Sunday School, and the weekly

dinners that the partners of Hunters’ Bank had circling around each

partners’ home.

In 1803, Provost David Fergusson of Castlehill

died (no doubt worn out having been the chief magistrate of the town

thirteen times) and he left the estate of Castlehill (with its vote in the

County elections) to his nephew Patrick Ballantine, who retired from Jamaica

(and his constant badgering of Charles Douglas, Dr Patrick’s brother, for

cash towards his debts) to come home and rebuild Castlehill into a modern

mansion. When Patrick himself died in 1810, John was his heir and he lived

in the new house for his few remaining years.

The primary reason, though, that the world

remembers this kind, enlightened man, is his interest in and patronage of

the greatest Ayrshireman, nay Scot, Robert Burns. Following his acquisition

of a copy of the Kilmarnock edition (in likelihood through Robert Aiken who

was a distant relative), he sought to assist the poet, in several ways, both

literary, in offering an advance to meet the paper cost for a possible

second edition at Kilmarnock and commercially, in discounting bills for

Robert’s farm. He was also a subscriber to the Second (Edinburgh) Edition,

which as discussed contained The Brigs of Ayr dedicated to him by the

poet. They maintained a correspondence including some of Burns’s most

characteristic letters until some time after the poet moved to Dumfries

when, for no apparent reason, the epistolatory flow ceased.

The letter Robert wrote to him from Mossgeil on

27 September, 1786, enclosing the manuscript and dedication of ‘The Brigs of

Ayr, captures the strength of attachment between these men.

Sir,

I am no stranger to your friendly offices in my

Publication; and long since I could and had that been the only debt I owed

you, I would long since have acknowledged it; as the next Merchant's phrase,

depressed up a little, would have served my purpose.

But there was is a certain cordial friendly

welcome in my reception, when I meet with you; an certain apparent heart

warm, honest joy at having it in your power to befriend a man whose

abilities you were pleased to honour with some degree of applause --

befriending him in the very way too most flattering to his feelings [...]

I have taken the liberty to inscribe the

inclosed Poem to you. I am the more at ease about this, as it is not the

anxiously served up address of the Author wishing to conciliate a liberal

Patron but the plain honest Sincerity of heartfelt Gratitude. Of its merits

I shall say nothing; as I can truly say that whatever applauses it could

receive would not give me so much pleasure as having it in my power, in the

way I like best, to assure you how sincerely I am,

Sir,

Your much indebted humble servant.

ROBERT BURNS.

Five years after his protégé’s early death,

Ballantine asked his friends Captain Kennedy and Fergusson to approach

Hamilton Paul to hold the first ever Burns Supper on 21 July 1801 in the

very Burns Cottage itself. Ballantine presided at each of the Anniversary

Dinners from 1801 to 1804, and was an active chairman: his toast from the

second meeting, on 29 January 1802 was captured by the local newspaper

(although I would bet it was ghost written by the Reverend HP):

Smooth glide thy pure

currents, thou favourite river,

May the loveliest

nymphs grace thy margin for ever;

Never fading thy flowers, ever green be thy braes,

Nor a Poet be wanting to warble thy praise;

May the minstrels of spring aye renew in each grove,

The wild hymn of gratitude, pleasure, and love;

Let no thorn in thy thickets e'er savagely dare

The innocent bosom of beauty to tear;

And blest be thy mansions with plenty and peace,

Till arrested by fate thy meanderings cease!

In 1805, possibly at Ballantine’s request,

Hamilton Paul reported that ‘it was suggested that as many of the members of

the club were advanced in years and the winter an inconvenient season for

them to dine in the cottage, the Anniversary should be transferred from

winter to summer and it was resolved that Lieutenant Colonel Cameron should

be convener of the meeting.’ Ballantine continued to attend these annual

celebrations but ill-health occasioned his absence in 1810, and he did not

attend another until his death on 15 July 1812. He left Castlehill to a

cousin and his two elderly sisters.

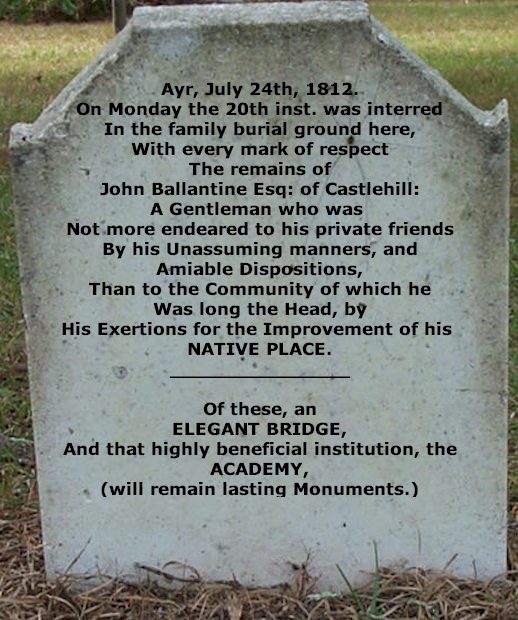

He is buried in the kirkyard of Auld Kirk of

Ayr, with the following memorial prominently on the church wall nearby:

John Ballantine had no

children, but more importantly, he left a legacy that can be felt in his

home town even today (and few of us can make that claim after 202 years).

Most people think of the Scottish Enlightenment as a lighting flash on the

Firth of Forth that spawned the New Town of Edinburgh and its societies and

soirees. This short, but affectionate, remembrance of an Ayrshire man

reminds us that the Enlightenment was a national phenomenon which is, of

course, why it had such a profound effect on Scottish life and letters and

why the heart-stopping and eye-opening poems of Ballantine’s young friend

found its place in the hearts of so many millions.

©

Clark McGinn, 2014.

|