|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

One of the movers and

shakers in the Burns community goes quietly and happily about his work with

great distinction. He has planned and coordinated as many conferences on

Burns as anyone I know, and he did it with much style and grace. He does not

seek attention. He is a behind-the-scenes fellow who helps advance the cause

of 18th century literature and who is a strong proponent of

Robert Burns. He is diligent in his research; his footnotes are impressive

and clearly give credence to his research. His writing skills exhibit

clarity that few possess. Say hello again to Professor Patrick Scott.

I have written so much about

Patrick in previous pages of Robert Burns Lives! that it would be

very easy to simply quote from those articles. But instead I ask you to read

“A Tribute to Patrick Scott” in Chapter 135 of our Index. This accolade was

written on the occasion earlier this year of his well-attended retirement

celebration hosted by his colleagues at the University of South Carolina.

Welcome home, Patrick! (FRS: 9.6.12)

Robert Burns’s

First Printer: John Wilson of Kilmarnock

Part 1: The Book Market in Burns’s Ayrshire

By Patrick Scott

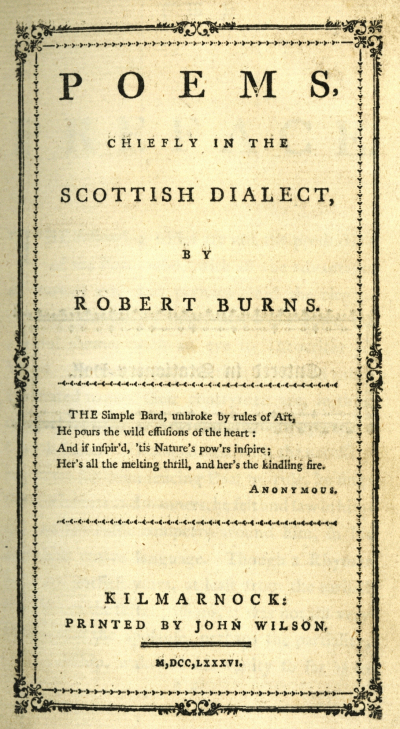

The most

coveted book for any Robert Burns collector is Burns’s first book, Poems,

Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, printed in 1786 in the small

market-town of Kilmarnock in the west of Scotland by John Wilson. That one

book has deservedly given its printer lasting fame, but who was John

Wilson? Given that Burns’s book was unique, what other kinds of books did

Wilson and his brother Peter publish, and what can the books published under

the Wilson imprint tell us about the community and culture in which Burns

became a poet?

Robert

Burns—Kilmarnock edition

Burnsians have

long been interested in some of the “new” books that Wilson printed,

especially the volumes of poetry by other Ayrshire poets. They have paid

less regard to the many reprints of earlier works that were the bread and

butter of the provincial book trade in eighteenth-century Scotland. These

reprints are the primary focus in this first part of a two-part survey of

Wilson as printer and publisher; the second part will shift focus to the new

books he printed. It was the reprint trade that had precipitated major

legal cases in the 1760s and 1770s over the “question of literary property,”

cases in which the right of Scottish publishers to reprint older works was

eventually vindicated, and it was the reprint trade, not new books, that

made provincial bookselling financially viable in Burns’s time. The

Edinburgh bookseller William Creech was quoted in 1774 as lamenting that the

multitude of cheap reprints was undermining the quality of Scottish

publishing:

In every

little town there is now a printing press. Cobblers have thrown away their

awl, weavers have dismissed their shuttle, to commence printers. The

country is over-run with a kind of literary packmen, who ramble from town to

town selling books ... (MacDougall, as below, 38).

John Wilson,

who made a career as a bookseller and printer, and was eventually a local

magistrate, was a more established and upstanding citizen than that, but his

business also was made possible by the expanding opportunities of the

reprint market. Indeed, the list of works that he published, especially

during his first ten years, is a very interesting index to the character of,

and strains within, contemporary Scottish small-town culture.

There has been

growing research interest recently in this kind of question. While one

could cite a host of earlier individual studies, the book that defined the

subject for modern researchers was Richard Sher’s prize-winning study The

Enlightenment and the Book: Scottish Authors and their Publishers in

Eighteenth-Century Britain (2006). Sher was followed by Mark Towsey’s

Reading the Scottish Enlightenment: Books and their Readers in Provincial

Scotland, 1750-1820 (2010), which focuses on local libraries and the

availability of Enlightenment books to readers. These have been followed up

earlier this year by The Edinburgh History of the Book in

Scotland, Volume 2: the Eighteenth Century, edited by Stephen Brown and

Warren MacDougall (2012). This 600-page volume has over fifty essays by

experts on different aspects of Scottish book production and publishing,

including an essay by G. Ross Roy on “Robert Burns and his publishers.” For

detailed information on Wilson, however, though there have been some

interesting shorter pieces, the best sources are still two older studies, a

1967 article by Frances Thomson and a substantial 1976 list of

locally-published items by Carreen Gardner (see below for references).

John Wilson

(1758-1821) is representative of the growing importance in 18th century

Scotland of small-town printers and booksellers. By 1780, when he was just

twenty-two, Wilson had already established a shop in his home town of

Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, selling books and stationery. Kilmarnock, which grew

from some five thousand people in 1763 to 6,700 in the early 1790s, was the

largest town in the county. As his next step in business, Wilson bought a

wooden printing-press and other equipment that had been brought to the

county by another bookseller, Peter M’Arthur, and began doing “jobbing

work”—advertisements, legal notices and the like—in a printing-shop in Star

Inn Close, Kilmarnock. From 1782 on, alongside the regular work of a

jobbing-printer, Wilson began printing quite substantial books. Some of the

books Wilson printed, especially as he started, were reprints of older

standard titles (which could be sold not just in Kilmarnock but to

booksellers in other towns), but once he was established he also undertook

to print new works, and these would typically be printed either at the

author’s expense or (as with Burns’s poems) by gathering advance payments or

“subscriptions” from friends and well-wishers. In 1790, Wilson moved the

printing press, under the supervision of his brother and partner, Peter

Wilson, from Kilmarnock to the county town of Ayr, and subsequently

established the first county newspaper, the Ayr Advertiser. The firm

would last, in various permutations of partnership, another thirty years,

but the Kilmarnock imprint itself lasts less than ten years (1780-1790), and

books published by the Wilsons after 1790 carry Ayr or Air as place of

publication.

As well as the

Kilmarnock Burns, the Roy Collection at the University of South Carolina now

has some twenty-eight Wilson titles from Kilmarnock and Ayr, and these

provide a fascinating window into Burns’s world. (Other similar Scottish

small-town presses well represented in the collection include Neilson of

Paisley, Morison of Perth, and Tullis of Cupar.) While both Sher’s study and

the Edinburgh History acknowledge the existence of Scottish printing

outside Edinburgh and the other university cities, and Towsey’s study is

primarily concerned with provincial readers, the emphasis in all three is

more on cultural change than the cultural continuities of small-town

Scotland. An imprint study of the Wilson firm can cast an interestingly

different light on Burns’s Scotland.

As one would

expect, a significant proportion of the books Wilson published were

religious, and traditional in their religious approach. From Burns’s early

satires, we might well think of late eighteenth-century Scotland religion as

an evenly-matched struggle between the unco’ guid and the restless young.

From a bookseller’s perspective, certainly in the West of Scotland, it was

not evenly-matched. The religion of the seventeenth-century Covenant, of

the English Puritans, and of such eighteenth-century traditionalists as the

Marrow-men and the Seceders, was still a much safer investment than the

newer ideas of Enlightenment Scotland. In 1781, before he sold the press to

Wilson, M’Arthur had reprinted a sermon originally preached by Gabriel

Wilson during the Marrow controversy in 1721. The first books to carry the

Wilson name were reprints in 1782 of the Covenanter Samuel Rutherford’s 1633

sermon, Christ’s Napkin, and of the secession leader Ralph Erskine’s

Gospel Sonnets, first published in 1726, followed in 1783 by a

reprint of a work by the leading orthodox minister in Edinburgh, John

Erskine, An Attempt to Promote the Frequent Dispensing of the Lord’s

Supper, first published in Edinburgh in 1749.

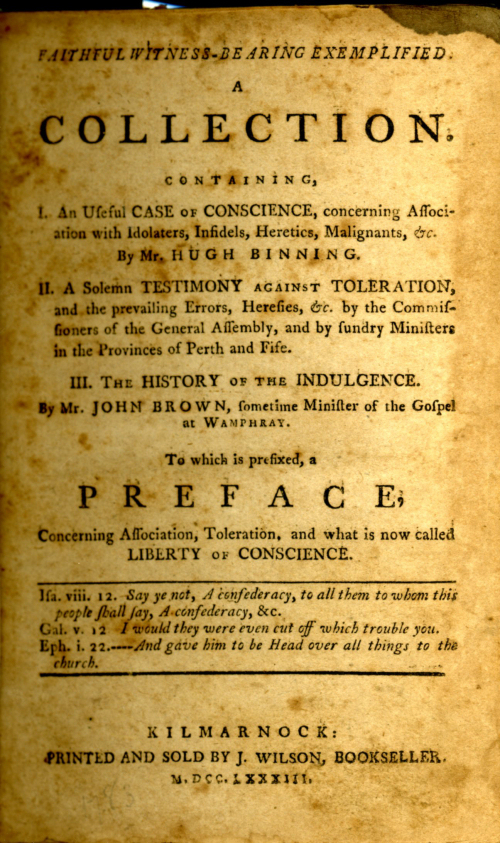

The earliest

Wilson volume in the Roy Collection is also a reprint of this kind, and also

dated 1783. This is a collection of three works originally published in

1693, 1649, and 1678 (each with its own title-page and also sold separately)

that were sold together under the collective title Faithful

Witness-Bearing exemplified: A Collection. The book came with a new

general preface (“concerning

association, toleration and what is now called liberty of conscience”)

by John Howie, the local keeper of Covenanting tradition and author of the

often-reprinted Scots Worthies. As to “what is called liberty of

conscience,” authors and editor were all against it: as his subtitle shows,

the first of the three authors, Hugh Binning, was specifically

against Associations and Confederacies with Idolaters,

Infidels, Hereticks, Malignants, or any other known Enemies of Truth and

Godlinesse, etc. One might perhaps argue that the very vehemence or

absolutism of such reprints indicates that by the 1780s the views they put

forward were already under pressure and felt by their proponents to be

losing ground. Nonetheless, the reprinting suggests the views resonated

with a significant group of book buyers in the community.

If this

was what sold well in Kilmarnock, it is small wonder that Burns chose

carefully which of his own poems he should include in his first volume and

that he chose to exclude his sharpest religious satires, such as “Holy

Willie’s Prayer.”

Faithful

witness-bearing

When Wilson reprinted works of this kind, it was not for sale

only in his own shop. Among the earliest books to carry Wilson’s name is

the Erskine reprint, which was printed by Wilson, but to be sold by Peter

M’Arthur

in his new shop in Paisley. Conversely, that same year, Wilson was listed

among several booksellers for Thomas Walker’s Essays and Sermons,

which had been printed by Murray & Cochran in Glasgow. This was a

well-established pattern for small-town booksellers: Burns’s brother

Gilbert reports that when Robert Burns was a boy, his father had subscribed

for a six-volume reprint of Stackhouse’s New History of the Holy Bible,

first published in 1737 but reprinted in Edinburgh in 1764 “for James Meuros,

Bookseller, in Kilmarnock.” This was the reprint at issue in a pivotal legal

case, Hinton, vs. Donaldson (1773), where against the claims of English

publishers to perpetual common-law copyright, the Scottish Court of Session

upheld the rights of the Scottish reprinters, among whom Meuros was cited as

co-defendant (Pottle 98-101). Gilbert also notes that William Burnes had

borrowed for his sons a copy of Salmon’s New Geographical and Historical

Grammar, first published in 1749, but reprinted in Edinburgh in 1767,

specifically for Meuros, who had issued a subscription proposal in 1765 with

a Kilmarnock imprint. Even after he started printing on his own press,

Wilson still appeared on title-pages as selling works printed elsewhere, as

for instance in a 1785 reprint of the Confession of Faith and Catechisms,

printed in Glasgow by Bryce, surely the ultimate steady seller for an

eighteenth-century small-town Scottish bookseller.

The first thirteen titles Wilson published were all

religious, and all conservative. It is not till 1784 that he branches out

to risk more secular works. Even the first secular publications were still

reprints of safe steady sellers. One of the first was a letter-writing

manual that had first been published in London in 1758, Dilworth’s

Complete Letter-Writer: or

Young Secretary’s Instructor. Containing a Great Variety of Letters on

Friendship, Duty, Love, Marriage, Amusement, Business, &c.;

Burns’s uncle had gone into Ayr to buy this very practical manual for his

nephews’ education, but came back by mistake instead with a different volume

of literary letters by eminent writers (recently identified by Robert

Crawford as John Newbery’s Letters on the Most Common, as Well as

Important Occasions in Life, 1756 etc., also in the Roy Collection),

with lasting results for Robert’s epistolary style and ambition.

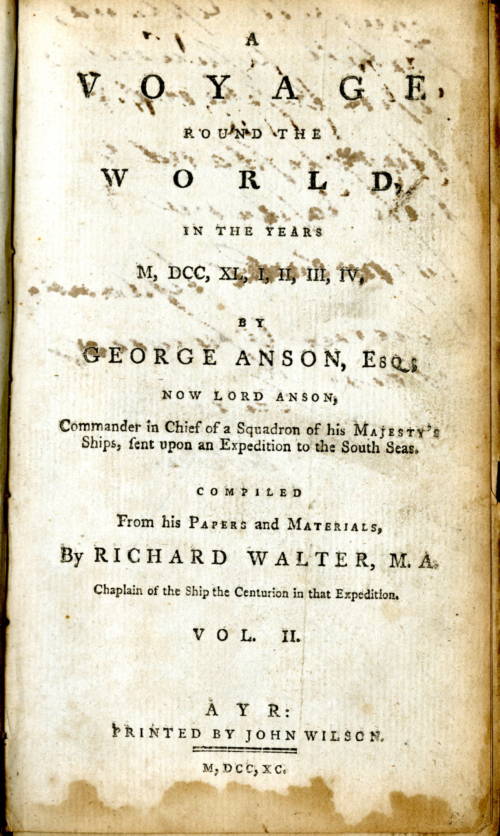

In 1785,

Wilson followed Dilworth’s manual with a cheap, small-format reprint of one

of the most dramatic eighteenth-century exploration narratives, first

published in 1748, Lord Anson’s Voyage Round the World, in the years

MDCCXLI, II, III, IV . . . Compiled from his Papers and Materials. This

is perhaps a reminder that one of Burns’s motives in publishing his poems

would be to raise money to leave the west of Scotland and seek his fortune

overseas; Burns and other young men like him (one thinks of young James

Currie from Dumfries sailing to Virginia or the radical poet Alexander

Wilson of Paisley going to Pennsylvania) might also have found out about the

voyages on which they were embarking from returning sailors or about their

hoped-for destinations from geography books like Salmon, but travel and

exploration sold well; the Anson title sold well enough to encourage Wilson

to do a second reprint in 1790, soon after the move to Ayr.

Anson

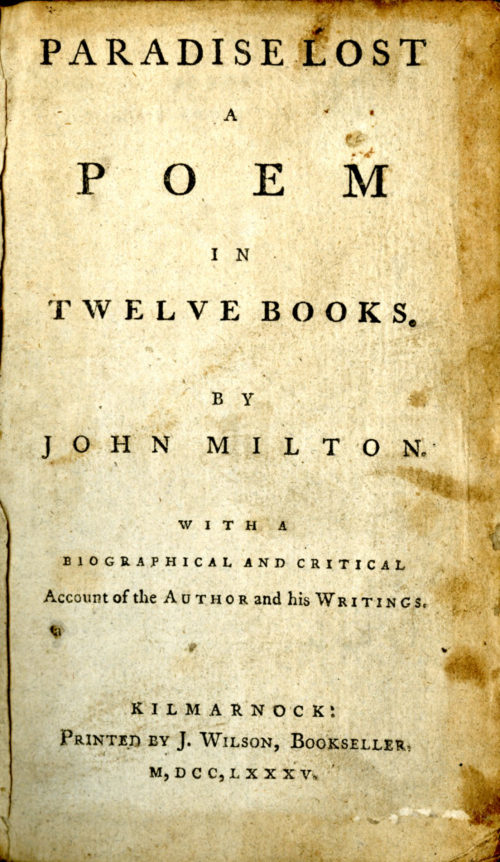

That same

year, 1785, Wilson published his first literary title, again a reprint of a

standard work in regular demand. This was his small-format edition of John

Milton’s Paradise Lost, first published in 1667, and one of the

titles the London booksellers had tried in vain to protect from Donaldson

and the Scottish reprinters. While we don’t know that Burns bought his copy

from Wilson, we do know he read Milton in this kind of small-format reprint;

on June 18,

1787, Burns wrote to his friend William Nicol that he had “bought a pocket

Milton, which I carry perpetually about with me” (Letters, ed. Roy,

I: 123). Milton’s Paradise Lost proved to be Wilson’s

most popular publication, being reprinted once more at Kilmarnock in 1789,

and then twice more after the press moved to Ayr, in 1791 and 1795. In this

period, before the invention of stereotype plates, each new reprint required

the complete resetting of all 300 pages of type. Between the Roy Collection

and the library’s Robert J. Wickenheiser Milton Collection, the University

of South Carolina has copies of all four Wilson editions of Paradise Lost.

Paradise Lost

1785

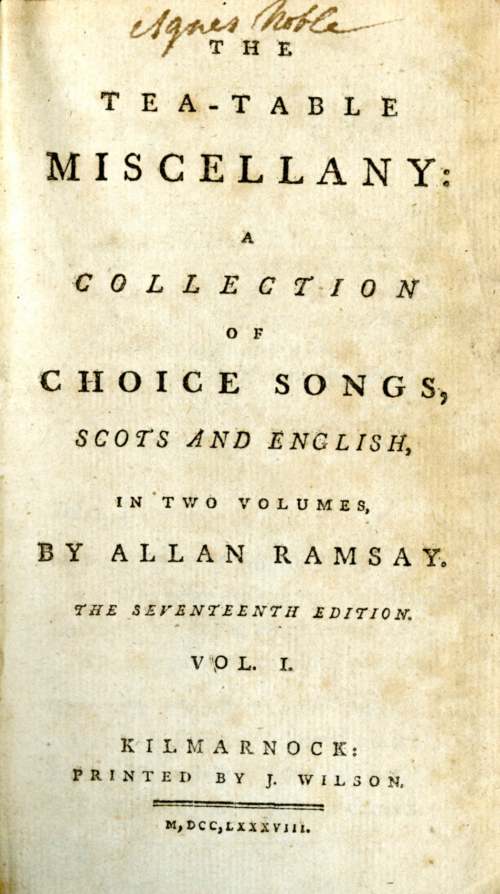

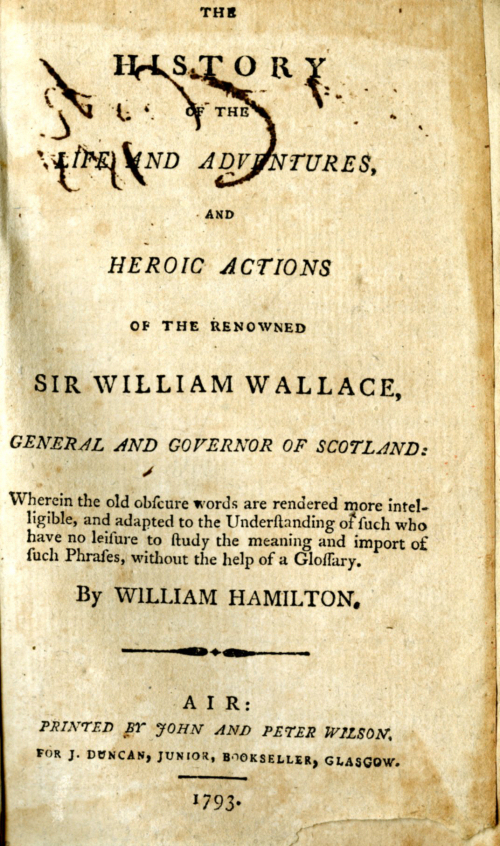

Wilson would

go on to do other reprints of older literary works, particularly older

Scottish works, notably Allan Ramsay’s Tea Table Miscellany

(Kilmarnock, 1788), Blind Harry’s History of the Life and Adventures and

Heroic Actions of the Renowned Sir William Wallace, as modernized by

Ramsay’s contemporary William Hamilton of Gilbertfield (Ayr, 1793, reprinted

1799), and King James I’s The Kingis Quair (Ayr, 1815). Reprinting

Ramsay did not show that Wilson had an unusual commitment to Scottish

authors, though it does show Ramsay was in continuing local demand; Wilson’s

Kilmarnock rival Meuros had appeared in 1784 on the title page of a reprint

of Ramsay’s Gentle Shepherd.

Tea Table

The copy of

the 1793 Wallace in the Roy Collection carries the ownership

signature of ‘Jane B Welsh, Haddington” (later better known as Jane Welsh

Carlyle), evidence that Wilson’s reprints were not just for local sale. The

date is interesting, too: it was in August 1793 that Burns wrote his song

about Bruce at Bannockburn, beginning “Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,”

though as he told Mrs. Dunlop in 1786 the life of Wallace was one of the

books he had pored over as a boy years before.

Wallace

The reprinting

of standard works, both religious and secular, continued to be an important

part of Wilson’s business throughout his career. The reprints were nearly

always done in the smaller duodecimo format, and printed sheet by sheet,

between other printing jobs. Indeed, they were usually set up as

half-sheets, further reducing the quantity of type that was tied up at any

one time. How the book work was fitted in around the job work, and later

the newspaper, is shown by the extract for July 9, 1803, that Frances

Thomson published from the firm’s manuscript “Case Book.” This was a record

of the work done by Wilson’s compositors, broken down into separate jobs,

with the value of each piece of work noted. That day, the shop had set type

for two half-sheets of a book (a school text of Caesar), three folio

playbills, a quarto public notice, four octavo pages from the Scheme

appended to a Berwickshire Report, lease particulars for a farm and also for

a house, an advertisement for a local grocer, one form letter for “A.

MCreath,” and an invitation card for a ball (Thomson p. 50). The skilled

work on setting Latin for the book was set down as worth 5s. 6d., while the

other work, the jobbing work, was worth more than double that, 11s. 6d.

As time went

on, the Wilsons were reprinting works for much wider wholesale distribution,

as with reprints of schoolbooks (classical texts from Virgil, Caesar and

Sallust, Mair’s Latin Syntax, books on arithmetic, English grammar,

spelling, even French), Goldsmith’s History of England (Air: Wilson,

for Andrew Brydon, bookseller, Glasgow, 1799), and Arthur Masson’s

Collection ... from the Best English Authors, which Burns had studied

with John Murdoch in the 1760s (Letters I: 135), reprinted by

Wilson in 1796. Their 1797 reprint of the Shorter Catechism was printed in

Ayr for a Glasgow bookseller, while their 1798 edition of the Metrical

Psalms was printed for sale by four Glasgow booksellers and one in Paisley.

Their last (1795) reprint of Milton’s Paradise Lost, printed in Ayr,

nonetheless carried as the most prominent firm on its title-page “London:

Vernor and Hood.” Yet mixed in with this more secular reprinting continued

to be older, sterner standbys, such as Thomas Boston’s Human Nature in

its Fourfold State (Air: J. & P. Wilson, 1797), originally published in

1720-29 and said to be the most widely reprinted Scottish book during the 18th

century.

How do these

reprints relate to what we know from other sources about late

eighteenth-century Ayrshire as a place of cultural, economic, and religious

change? First, the expansion in the provincial book trade represented by

Wilson’s press and its record of reprinting was in itself a sign of economic

development, but there was some time-lag between economic development and

its cultural consequences. In an important recent article, the Oxford

historian Bob Harris has taken Kilmarnock as one of his test cases for

investigating cultural change in eighteenth-century Scottish towns, and

concluded that it was only in the last decades of the century that towns of

that size showed any dramatic economic and cultural development. If

anything, Kilmarnock was slower than that.

Reprinting was

central to Wilson’s publishing business, but even his reprinting differed

from the reprinting that was revolutionizing the book market for Edinburgh

and London publishers. William St Clair’s influential study The Reading

Nation in the Romantic Period makes the legal decisions over copyright

from the 1760s and 70s a major turning point in cultural history, because it

permitted the Edinburgh printer Donaldson and his imitators to issue great

series of out-of-copyright standard authors as the British Poets, British

Dramatists, British Novelists, and so on, creating for the first time a

sharp division between the business of republishing older works and that of

publishing new ones. Bookseller-printers in Paisley and Glasgow regularly

issued rather similar kinds of book to those that Wilson printed, showing as

his reprints showed as much cultural continuity as they do change.

Ayrshire

readers like Burns were not of course dependent on Wilson’s reprints, or

Paisley or Glasgow, for what they read. As Mark Towsey has documented, both

through direct purchase, through local booksellers and subscription or other

libraries, or through borrowing from friends (as Burns borrowed from Robert

Riddell), readers had access to a much wider and more modern world than that

represented by locally-printed books like Wilson’s. Robert Burns’s letters

to Peter Hill ordering books for the Monkland Friendly Society (Letters,

ed. Roy, II: 9-10, 19-20), and his subsequent report about it in Sinclair’s

Statistical Account of Scotland (in Letters, II: 106-108),

indicate that there were Ayrshire readers whose book world embraced national

developments. Even for Monkland, however, the ordinary members wanted books

more like those that Wilson published (Knox’s History of the Reformation,

Adam Gib’s Act and Testimony of the Secession), and Burns and Riddell

were once reduced to pretending to order for the Society a second copy of

Watson’s Body of Divinity, obviously in high demand for borrowing,

while secretly instructing Hill to write back that the edition they asked

for was no longer obtainable (Letters, II: 10).

Bob Harris, in

the article cited above, argues that the many economic and social changes in

late eighteenth-century small-town Scotland were not simply modernization,

or convergence on a trickled-down metropolitan culture, but one where

“different local and national traditions ... merged without losing their

inflections in local settings” (Harris 140). The core reprint work of John

Wilson’s Kilmarnock print-shop certainly represents these “local ...

traditions” and “inflections,” and some of the later reprints (Milton,

Ramsay, Anson) do follow, at a decent distance, trends in the wider book

market. Nonetheless, the overall impression is less of a merger with

national culture, however inflected, than of a conscious

market-differentiation from, even a resistance to, wider cultural

developments. It makes Wilson’s historic role as printer of Burns’s first

book all the more extraordinary.

Part 2 of this

essay will take up the question of a local Kilmarnock book culture in

reassessing the new books by local authors that carry the Wilson imprint.

References

Brown,

Stephen, and Warren MacDougall, eds., The Edinburgh History of the Book

in Scotland, II: the Eighteenth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press, 2012).

[Dawson,

Bill], “Kilmarnock Clubs Commemorate the Printer,” Burns Chronicle

(Summer 2011): 2-3.

Gardner,

Carreen S., Printing in Ayr and Kilmarnock: Newspapers, Periodicals,

Books, and Pamphlets Printed from about 1780 until 1920 (Ayr: Ayrshire

Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1976).

Harris, Bob,

“Cultural Change in Provincial Scottish Towns, c. 1700-1820,” Historical

Journal 54:1 (2011): 105-141.

MacDougall,

Warren, “The Emergence of the Modern Trade,” in Brown and MacDougall

(above), 23-39.

Mackay, James

A., “Wilson, John,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Pottle,

Frederick A., The Literary Career of James Boswell, Esq. (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1929).

St Clair,

William, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Sher, Richard,

The Enlightenment and the Book: Scottish Authors and their Publishers in

Eighteenth-Century Britain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Thomson,

Frances M., “John Wilson, an Ayrshire printer, publisher, and bookseller,”

The Bibliotheck, 5:2 (1967): 41-61.

Towsey, Mark

R.M. Reading the Scottish Enlightenment: Books and their Readers in

Provincial Scotland, 1750-1820 (Leiden: Brill, 2010). |