|

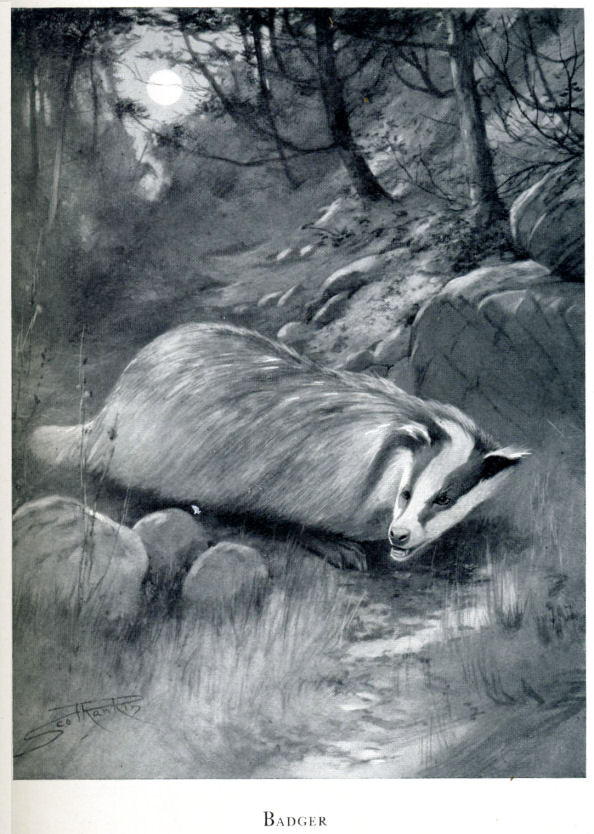

A QUEER, quaint, old-world

animal; clumsy in form and bizarre in colouring, timid and shy, shunning

daylight, man and his works, the badger, the largest of our remaining

carnivora, is also one of the most interesting. From its rarity and

secluded habits it is one of the least generally known; indeed people live

for years in its immediate neighbourhood without being aware of the fact,

unless through some accidental occurrence. Once generally distributed over

the whole country, it is even to-day not so uncommon as is often supposed;

although doubtless a decreasing species it can hardly yet be said to be

verging on extinction, and is still to be found, more or less sparsely,

from the North of Scotland to Cornwall and in many parts of Ireland

The badger is classed with

the Ursidac, and in some ways shows considerable affinity to the

bears, as for instance in his great muscular

development, shambling gait, and chiefly in

his plantigrade method of walking with the whole foot, from heel to toe,

upon the ground. The thirty-eight teeth with which his enormously powerful

jaws are armed betray the omnivorous nature of his diet. He measures some

3 feet in length, including the short tail of 5 or 6 inches. His short and

powerful legs and feet are provided with long and strong claws,

particularly the fore-paws. His height is barely a foot, so that with his

long coat he appears to brush the ground. In colour the upper parts are of

a uniform silvery grey, the individual hairs being banded with

blackish-brown and white, the underparts and legs are black, the head

white with a black stripe on each side from the nose over the eye and ear.

A full-grown badger weighs from 20 to

30 lbs., the male being somewhat the heavier. Mr. A. E. Pease, M.P., in

his monograph on the badger,, says that they have been known to

weigh up to about 40 lbs.; but that the heaviest that he had ever weighed

in his own experience scaled over 35 lbs. The jaws are immensely powerful,

the under-jaw, as already remarked by Blasius, being interlocked with the

upper jaw ; the canine teeth of the under-jaw are particularly long and

strong. Under the tail is situated a glandular pouch in which is secreted

a strongly-smelling substance. Opinion seems to be divided as to the use

of this secretion, some holding that the animal derives nourishment from

it during its winter retirement-a view which one is somewhat surprised to

find favoured by Mr. Pease-it seems too much akin to the old belief that

the bear subsisted by sucking its paws in winter, to obtain ready

credence. Von Tschudi, speaking of this belief, remarks simply that it is

false.

Of strictly nocturnal

habits, the badger spends the day below ground in his earth, in the

formation of which he shows perhaps more intelligence than in other

directions. The tunnel is long and deep, and frequently branching, each

terminating in an enlarged living chamber, and each earth having several

exits or bolt-holes. The living-chamber is warmly furnished with dry

grass, moss, leaves and bracken, replaced yearly by fresh material. Mr.

Pease gives an interesting account of the method by which the badger

carries in his bedding, retiring backwards into the earth with the heap of

material gathered into a bundle between his fore-paws and his head. The

badger is often spoken of as solitary in its habits, but this seems to be

erroneous ; he is monogamous and is said to pair for life. Mr. Pease once

enjoyed the singular spectacle of seeing no less than seven full-grown

badgers issuing at night-fall from one earth. Another imputation against

him, that of foul-smelling and unclean habits, is also unfounded. His

earth is usually sweet and clean, the animal retiring when necessary to

some distance from his habitation. There is a tradition, repeated by the

German writers, that the fox is in the habit of evicting his powerful

neighbour from his comfortable abode by means of be-fouling the chamber of

malice prepense ; but this also is groundless fancy, for foxes and

badgers are known to inhabit the same earth; such earths, it must be

remembered, being often very large and with many ramifications. Here,

about the month of March, the young come into the world, according to Mr.

Pease usually two, sometimes three, never more than four in number,

although the German writers say from three to five, and give January and

February as the usual dates ; but locality and climate may account for the

difference.

In the matter of food the

badger is decidedly omnivorous, nothing, almost, seeming to come amiss.

All manner of roots, vegetables and fruits, beetles and insects of all

sorts, reptiles, snakes, young birds, eggs, mice, and the smaller animals

generally, all seem welcome. Honey and wasp-grubs have special attractions

for them as for their distant relative the bear ; and on the continent of

Europe they do at times much damage in the vineyards. In this country

there is no doubt but that young rabbits are a favourite delicacy, and it

may be accounted to the badger for righteousness that he helps to keep

down these ubiquitous pests.

On the whole he may be

regarded as a harmless, if not absolutely a useful animal; but that an

occasional individual may develop abnormal and vicious propensities cannot

be denied. A striking instance of such depravity has come to my knowledge.

A forester living in a remote cottage in the heart of one of our largest

deer-forests had a number of fowls in a rude turf-covered out-house. One

night there was a great outcry among the fowls, and in the morning it was

found that some animal had forced an entry and carried off one or more of

the inmates. The door was made secure, but next night the alarm was

renewed. At daybreak the forester found that the burglar had this time

obtained entrance through the roof, and being unable to return that way,

remained a prisoner. Fetching his gun, he had the satisfaction of slaying

a large badger, caught flagrante delicto. Such cases must, however,

be considered as exceptional, and analogous to that of the squirrel that

has acquired the bad habit of robbing little birds’ nests of eggs and

young, or of the very rare case of a kestrel that has taken to carrying

off young pheasants from the rearing-field; perhaps as protest against

modern unsportsmanlike excesses in artificial game-rearing!

A number of years ago there

was some correspondence in The Field as to the alleged destruction

of fox-cubs by badgers. In the end the question remained undecided as to

whether such cases as had undoubtedly occurred had been the work of some

bad-tempered old badger, or of an old dog-fox of similarly unamiable

character; they could not be attributed to any general habit of the

species as a whole.

It seems to be agreed on

all hands that badgers are a thirsty race and drink much water. The

popular notion that the badger hibernates, as the dormouse, for instance,

does, is incorrect. They spend, indeed, much of the winter in sleep in

their cosy underground chambers, especially in long-continued hard

weather; but the unmistakable evidence of their footprints shows that they

do come forth at no very long intervals.

Although the badger may

sometimes be seen sunning himself just within the mouth of his earth, he

seldom or never issues forth until nightfall, when he goes out on his

rounds after food, returning before daybreak; indeed, if he should

perchance have somewhat miscalculated his time, he comes shambling and

rolling home in a great hurry. One of the means of capturing him is by

means of a sack pegged inside the mouth of his main entrance during his

absence, with a running cord round the mouth of it, secured to a peg. The

badger, being found in his rambles and pursued by dogs, rushes in

precipitately and finds himself a prisoner. From his cunning he is

difficult to catch in ordinary spring traps.

The usual method of

capturing him, at least in the south, is by locating him first in his

tunnel by means of terriers, and then digging down until he is reached—a

work often of much time and toil. If the attention of the badger is not

continuously held by the terriers, he will scrape his way into the earth

faster than the hunters can dig after him. A full account of this

procedure is given by Mr. Pease in the monograph already mentioned. His

captives were not killed but released elsewhere.

In Scotland this method is

seldom very practicable, as our badgers are usually found in rocky ground

or in cairns; or else in earths on a hillside where digging would be too

much like railway-tunnelling to be feasible.

In Germany the Dachshund or

`badger hound' takes the place of our terriers. The German writers speak

of the flesh as eatable; and the fat had, both there and here, a great

reputation as a cure for rheumatism. There used to be, and may yet be, a

very general custom in South Germany of hanging a badgerskin as an

ornament on the harness or collar of farm horses.

Our ancestors had a quaint

belief that the badger's legs were shorter on one side than on the other,

the better to run along a hill-side! The difficulty of the return journey

does not seem to have occurred to them. This story probably had its origin

in the shambling, rolling gait of the animal.

The name badger is said to

be derived from Latin bladarius, a corn-dealer (cf. French

blaireau), from a supposed habit of storing up corn for winter supply.

Sir Herbert Maxwell tells us that in Middle-English Bager meant

corn-dealer. The Scottish name brock is of course the same as the

Gaelic and Irish broc, Cornish and Breton broch, the root

being apparently doubtful. There is evidence of its former wide

distribution in the place-names still extant, both in the Lowlands and,

more rarely, in the Highlands ; as `Brocketsbrae, Brockhole, Brockloch,

Brockwood, Broxwood' in the former; `Garaidh-nam-Broc,' badgers' den, to

take only one example in the latter.

The cruel pastime of

badger-baiting has also left its mark in the English language in the

every-day term 'to badger.'

The badger is found

throughout most parts of Europe and North and Central Asia, south of the

Arctic circle. According to Blasius it occurs in Italy, but not in the

other Mediterranean countries ; its American congener belongs to another

species. In our own country it is still to be found in many districts of

England, Scotland, and Ireland, although in ever decreasing numbers ; it

has apparently never been known in the Scottish Islands. It still exists

as a breeding species, to the present writer's knowledge, in Argyll and

Perthshire. According to Harvie-Brown it is to be found, though

decreasing, in Sutherland; is now quite rare in the North-west Highlands

generally, and in the Moray district. The late Mr. Robert Service, whose

death, since this paper was first written, is greatly regretted by all

Scottish naturalists, sent me the following notes as to the South-west of

Scotland :` At intervals of one or two years-at widening intervals it must

be said-a badger is heard of as being killed at some locality or other in

Solway. It is questionable if these are blood relations of the old

original stock. I believe they are not, but are most probably casual

introductions or casual wanderers from across the Borders. At the Glenkens

end of the Stewartry and in Annandale (upper part at least) there is no

doubt the old native badger remains, though it is to be found in very

meagre numbers indeed. In recent years I have noted their unmistakable

footprints on the shore.' With regard to the Border area the subjoined

notes from Mr. A. H. Evans, whose volume on the Fauna of the Tweed area'

may be further consulted, are of interest:` Badgers are known to occur

still in various parts, notably in the hills near Yetholm, and are not so

uncommon as might be supposed from the scanty notices in print. Badgers

are by no means exterminated in the Borders; they have probably held their

own for the last twenty years without any perceptible increase. Their

chief haunt is the Cheviots.'

For obvious reasons it

would be unwise to define more particularly the existing haunts of this

interesting animal. Is it too much to hope that those who are in a

position to do so will exert their authority and instruct their keepers

and foresters to leave the few remaining representatives of this ancient

British race in peace? |