There seems no general name to fit a part of Scotland

which has a very marked character, that lowland shelf lying beyond the

Grampians along the Moray Firth, where the counties of Aberdeen, Banff,

Moray, and Nairn are comparatively flat on the north side, but on the

south rise into grand mountains. The "back end of the Highlands" would not

be a dignified title; "Moray and Mar" is not an inclusive one, nor is

"Deeside and Speyside." One seems driven to indicate this as the district

of which Aberdeen is the capital, environed by the "four nations," Angus,

Mar, Buchan, and Moray, a division of local mankind copied by her

university from Paris.

Angus alias Forfar, and Kincardine alias

the Mearns, are lowland counties whose streams come down from a Highland

background to a coast-line of broad sandy links on the Tay estuary, and

weatherworn sandstone cliffs facing the open sea. We might linger here by

notable names beyond Dundee—Arbroath, with its ruined Abbey, the scene of

the Antiquary; Montrose, that Flemish-like town that has belied its

Cavalier name by rearing such sons as Andrew Melville, the reformer, and

Joseph Hume, the

Dunnottar Castle, Kincardineshire

economist; Stonehaven, seat of the Barclays of Ury

known in so different ways; and Brechin, with its Cathedral and Round

Tower, neighboured by castles old and new. In this countryside settled the

head of W. E. Gladstone's family, which, however, had moved from some

Gledstone or "Hawk's rock" in the south of Scotland to make fortunes

in England by trade. Sir Thomas, the great Liberal's brother, was a sound

Conservative, of whom is told that at an election, seeing a son of the

soil anxious to salute him, he stopped his carriage, and accepted a grasp

of the horny hand, qualified by "For the sake o' yer brither!"

By the wild glens of the North and South Esk let us

pass into Braemar, mountain region of Mar, the very cream of the

Highlands, whose highest summits, Ben Nevis left out of account, are

grouped in the south of Aberdeenshire. A generation ago Ben Nevis had not

been crowned by revolutionary surveyors, and Ben Macdhui was still held

monarch of Scottish mountains, keeping his state among the Cairngorms,

that here have half-a-dozen truncated peaks over or hardly under 4000

feet, Ben Muich Dhui, as Gaelic purists would have us call it, Brae-riach,

Cairntoul, the Peak of Cairngorm, Ben-a-bourd, and Ben A'an, heads of the

grandest mountain mass in the British Isles. This is the native heath of

sturdy Highland stocks, Farquharsons, Macphersons, and M'Hardys, Durwards,

Coutts, and Stuarts, of whose exploits and traditions more than one book

has been written. The folklorist will not be surprised to find how the

legends of Braemar re-echo those of other lands. Here a crafty female

Ulysses disables a giant and plays off on him a joking name that puts the

stupid fellow to a loss in calling for help. Here a MacTell wins his

liberty by shooting at a mark placed on the head of his wife, with an

arrow in reserve for the tyrant, in case his first aim should not be true.

Here an outlawed David in tartans lays his sword on the throat of a

sleeping Saul, then awakens him to reconciliation. Here a squire of low

degree comes by his high-born lass in the end; and the youngest of three

brothers of course wins the race of fortune, though handicapped like a

Cinderella.

This majestic crown of Scotland was chosen as the home

of our late Queen, but not then for the first time had Braemar and its

Castleton to do with royalty. If all tales be true, here was the cradle of

Banquo's race, he to whom the fateful sisters promised a long line of

kings, himself cut off as foretaste of so many violent ends. Malcolm

Canmore, son of Duncan, had a seat at Braemar, where he often lived with

his Saxon wife. He is said to have founded the autumn gathering, now tamed

into a spick and span show of holiday Highlanders, but in old days a grand

hunting party, more than once an assemblage for serious purposes. Taylor,

the Water Poet, on his " Penniless Pilgrimage," after being duly rigged

out in tartan, was taken by Lord Mar to the Braemar Hunt, when under

mountains to which this Cockney declares that "Shooters' Hill, Gad's Hill,

Highgate Hill, Hamp-stead Hill" are but mole-hills—

Through heather, moss, 'mongst frogs and bogs and

fogs,

'Mongst craggy cliffs and thunder-battered hills,

Hares, hinds, bucks, roes are chased by men and dogs,

Where two hours' hunting fourscore fat deer kills.

Lowland, your sports are low as are your seat,

The Highland games and minds are truly great!

It was under cover of the Braemar hunt of 1715, such a

gathering as a generation later had Captain Waverley for eye-witness, that

Mar hatched the Jacobite rebellion against George I., of which Scott aptly

quotes—

The child may rue that is unborn

The hunting of that day.

When the Pretender's standard was raised at the

Castleton, a hollow of rock by the Linn of Quoich, known as "the Earl of

Mar's Punchbowl," is said to have been filled with several ankers of

spirits, gallons of boiling water, and hundredweights of honey, a mighty

brew in which to drink success to that unlucky enterprise. In 1745, also,

the sons of Mar gave their blood freely to the cause of the Pretender,

though this time their lords were rather on the Whig side. Jacobite

sentiment remained strong in the district up to our own time. In 1824 was

buried at Castleton Peter Grant, who passed for being no years old, and

probably the last survivor of Culloden. To his dying day he would never

drink the Hanoverian king's health, yet this constancy seems somewhat

marred by the fact that, like Dr. Johnson, he accepted a pension from the

usurping line. In our time all devotion to memories of Prince Charlie have

been transferred to the sovereign lady who here would have lived as a

private person, so far as possible, but was sore hindered by the snobbish

curiosity that mobbed her even in the village church. Not that Highland

loyalty is always enlightened, if we may believe a story told by Mr.

George Seton of one Donald explaining to another the meaning of the

Queen's Jubilee: "When ye're married twenty-five years, that's your silver

wedding; and fifty years is your golden wedding; and if your man's deid,

they ca' it a Jubilee"! Braemar, indeed, with its bracing air and glorious

mountains, is not for every tourist. Hotels are few and dear; there is

little accommodation between cot and castle ; ramblers are not made

welcome in the deer forests around; and a countryside of illustrious homes

cannot be left open to all and sundry. When royalty be in residence, there

are no doubt keepers on the watch who have to guard something better than

game; and the trespassing stranger may find himself under observation as

strict as that of Dartmoor or Portland Island. In the promised elysium of

socialism both palaces and prisons may be turned into hydropathics; and

Braemar, 1000 feet above the sea, makes a princely health resort, with no

want of water. But access to this backwater of travel is itself somewhat

prohibitive to the strangers who would scamper over Scotland in six days.

The railway from Aberdeen comes no farther up the Dee than Ballater. The

direct access to Castleton is that of a long coach drive by the Spittal of

Glenshee. Pedestrians have the best of it in rough tramps up Glen Tilt or

Glen Clova from the south, or from Aviemore on Speyside, over a pass 2750

feet high, and with a chance of losing their adventurous way in

Rothiemurchus Forest, where Messrs. Cook's coupons are of no avail. Once

at the village capital of the district, one can visit most of its lions on

pony-back, the Falls of Corriemulzie and of the Garrawalt, the Linn of

Dee, Glen Cluny and Glen Callater, and even the top of the mighty Muich

Dhui, thus ascended by Queen Victoria. But the Cairngorms show their

jewels rather to him who, like

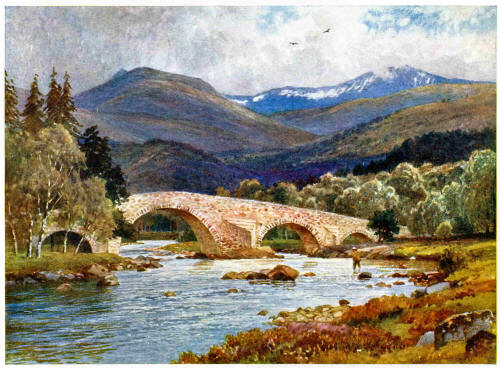

Old Mar Bridge and Lochnagar, Aberdeenshire

Byron, can roam "a young Highlander o'er the dark

heath," climbing "thy summit, O Morven of snow," and getting cheerfully

drenched among the "steep frowning glories of dark Lochnagar."

I am half a Scot by birth, and bred

A whole one, and my heart flies to my head.

Down the strath of the Dee, we descend to the lowland

country by beautiful gradations. Past the old and the new Castles of

Braemar, past Invercauld, Crathie, and Abergeldie, by the "Rock of Firs"

and round the "Rock of Oaks," is the way to Ballater, a neat little town

about a railway terminus, that makes it more of a popular resort. On the

other side of the river are the chalybeate wells of Pananich, one of those

unfamed spas held in observance by country folk all over Scotland. It was

at a farmhouse here that Byron spent his Aberdeen school holidays; and

happy should be the schoolboy who can follow in his steps, forgetting

examinations and cricket averages. But alas ! for the Aberdeen citizen

who, on trades' holidays, seeks this lovely scene when it is veiled in

mist and pelting showers. Him the Invercauld Arms receives as refuge; him

sometimes a place of sterner entertainment. There is also a temperance

hotel. Over the Moor of Dinnet, the railway takes us to Aboyne, another

pleasant resort on Deeside, along which we find hotels for tourists and

sportsmen, a hydropathic for health-seekers, a sanitorium for

consumptives; and thickening villages which, on the lower reaches, become

the Richmonds and Wimbledons of Aberdeen.

The Granite City of Bon Accord, with its old Cathedral

and Colleges, though a little overgrown by that upstart Dundee, comes

after Edinburgh and Glasgow in dignity, well deserving such attention as

Dr. Johnson gave to its lions. It has shifted its site from the Don

towards the Dee, between whose mouths it almost touches the sands, and

golf and sea bathing are among its pleasures, while in an hour the Deeside

railway runs one up into the Highlands. The old town has here dwindled to

a suburb, the new one laid out with striking regularity and solidity,

relieved by such nooks as the Denburn Gardens, across which Union Street

reaches by the tower of the Town Hall to Castlegate and the Cross, where a

colossal statue of the last Duke of Gordon and an imposing block of I

Salvation Army buildings represent a contrast of old and new times.

The Aberdonians, as is known, pride themselves on a

hard-headedness answering to their native granite. The legend goes that an

Englishman once attempted to defraud these far northerners, but the charge

against him was scornfully dismissed by an Aberdeen bailie: "The man must

be daft!" By the rest of Scotland, Aberdeen is looked on as concentrating

its qualities of pawkiness, canniness, and thrawnness; the Edinburgh man

cracks upon it the same sort of jokes as the Cockney upon Scotland in

general. The accent and dialect of this corner, strongly flavoured with

Norse origin and sharp sea-breezes, are quite peculiar. Norse origin, I

have said—and this has been held the main stock; but a recent

anthropological examination seems to show that even in seaward Buchan only

a minority of the school children are fair-haired. This sketch has nothing

for it but resolutely to forswear all such upsetting inquiries, which

nowadays go so far as to deny that any part of Scotland was purely Celtic,

and may some day prove us the original strain of Adam, whose migration

from Paradise to replenish the whole earth would be quite consistent with

a birthright in "Aberdeen awa'!"

Aberdeenshire is on the whole a matter-of-fact county,

by industry rich in "horn and corn," not without its pleasant nooks, and

on the south rising into those royalest Highlands. Buchan, the most

Aberdeenish part of Aberdeen, has a grandly rugged coast, with the

cauldron called the Buller of Buchan, and the Dripping Cave of Slains for

famous points, till lately much out of the way of travel, but now a

railway opens the golf links of Cruden Bay, between the old and the new

Slains Castles, whose lord, as Boswell observed, has the king of Denmark

for nearest north-eastern neighbour to the High Constable of Scotland.

Beyond, at this bleak corner, come the fishing towns of Peterhead and

Fraserburgh, where Erasers are as thick as blackberries, their name, along

the coast, being no distinction without a tee-name (agnomen) by

which a prosperous fisherman may sign his cheques, or an ill-doing one be

haled before the sheriff.

Inland, Aberdeen is rather the country of the gay

Gordons,no real Hielandmen,but emigrants from the south, of whom it is not

for me to say good words, inasmuch as I am kin to their hereditary

neighbours, which is as much as to say enemies, the Forbes. Yet, "in spite

of spite," one must admit that the Gordons flourish here, as on their

native borderland, in Poland, in Russia, indeed all over the world. The

"Cock of the North" has cause not to crow so boldly as of yore; and

regiments cannot now be raised by bounty of a Gordon Duchess' kisses; but

no less than three noble houses of the name have seats in this region,

lordliest among them Gordon Castle, the northern Goodwood.

The interior of this promontory has a prevailing aspect

of prosperous commonplace ; but here, too, are patches of romance and

superstition. Turriff, for instance, looks as quiet a little town as any

in the kingdom, yet at the Trot of Turriff was shed the first blood of our

civil wars. A pool in the river has a wild legend of family plate thrown

into it in those troubled times and found in guard of the devil by one who

dived for its recovery. This is a legend of Gicht, the home of Byron's

mother, that also has the subterranean passage of tradition, explored by

so many a piper, whose strains were heard dying away underfoot till they

went silent in what uncanny world! Near Gicht, Fyvie Castle contains a

secret chamber which must not be opened on pain of the laird's death, and

a stone that weeps for any approaching calamity to his house. There came a

new laird from London, a man of metropolitan scepticism, nay, even a

teetotaller, who regaled his scandalised neighbours with zoedone and such

like. He was reported to have given out an intention of opening the secret

chamber, but when pressed to do so in presence of certain local

dignitaries, he turned it off with a laugh. Mark the sequel: this

gentleman died suddenly very soon afterwards, so he might have opened the

fateful chamber whatever. One of the treasures of the castle, a

scrap of faded tartan from Prince Charlie's plaid, reverently preserved

under a glass case, was being exhibited to me by the parish minister, when

he felt himself tapped on the shoulder by

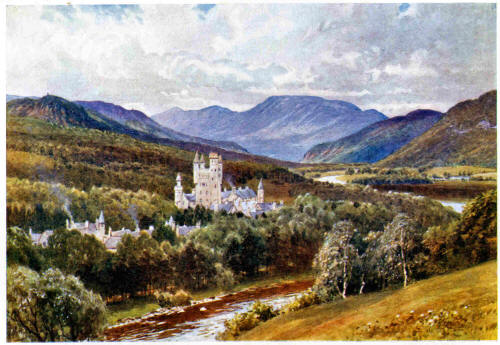

Balmoral, Aberdeenshire

the laird: "Did I hear you say the Pretender?"—a

softened form of Lady Strange's rebuke for the same lapse, "Pretender,

forsooth, and be dawmed to ye!" Another family in this district is

believed, and believes itself, never to have thriven since its head was

cursed by a Macdonald massacred in Glencoe. These are but samples of the

old-world ideas that turn up in the soil so carefully tilled by Johnny

Gibb of Gushetneuk.

Maybe the reader has never heard of Johnny Gibb— then

the loss is his. This book is well known in Scotland as a head of the "kailyard"

school that has flourished here since the days of Galt, though only of

late some caprice of taste gave it a vogue in the south. The examples most

popular in England do not always commend themselves to Scotsmen, who find

one and another aspect of their character overcharged to move the sighs or

grins of barren readers. At home is better appreciated such a writer as

William Alexander, who, risen from herd loon to editor of an Aberdeen

paper, knew his country-folk thoroughly, and depicted them with an art

that never oversteps the modesty of nature. One can hardly press Johnny

Gibb on a stranger, weighted as he is with an uncouth dialect and with a

serious stiffening of Disruption principles. But, to my mind, if Dr. John

Brown had not written Rab and his Friends, William Alexander's

Life among my ain Folk would be the flower of the kailyard: a

collection of humble Aberdeenshire idylls, as seen by a shrewdly humorous

eye, which can soften in not overstrained sentiment when it regards the

"little wee little anes" and "wee bit wifickies" that draw from sons of a

hard soil such endearing diminutives so characteristic of their

wind-bitten speech. If I am not mistaken, George Eliot's Scenes of

Clerical Life may have set a copy for these round-hand pages, not to

be taken as lessons in spelling, for only too faithfully do they reproduce

the local dialect. Johnny Gibb deals with the essence of Presbyterianism,

as distilled in Aberdeenshire Strathbogie during the non-intrusion

controversy. But this part of the country is, in fact, much divided as to

religious sentiment. About Aberdeen, the old Episcopal church is still

rooted in the soil, elsewhere in Scotland rather a greenhouse plant. The

Covenanters made war upon this prelatic city, and in its county Montrose

brewed the storm that swept down upon Whigamore strongholds. Hereabouts it

was Presbyterian divines who, after the Revolution Settlement, had

sometimes to be inducted at the bayonet's point upon unwilling

parishioners; then Cumberland's soldiers marching to Culloden could find

plenty of sport in burning non-juring meeting-houses. The Roman Catholic

element is still strong also, especially in the Highland part, many of the

clans, from Aberdeen across to Skye, having stuck to the old faith. The

Frasers have two heads, him of the Lovat branch a Catholic, but his

namesake of Saltoun a Protestant. Blairs College on Deeside is a notable

Catholic seminary, containing fine portraits of Queen Mary and Cardinal

Beaton. The Roman Cathedral of Aberdeen has no cause to hide itself, but

stands up boldly among its Free Church neighbours. In some parts of

Scotland, a Papist is looked on askance, but in this northern belt, the

two creeds have come to a modus vivendi, the parish minister

perhaps saying grace before dinner and the priest returning thanks.

On the same shoulder of Scotland a similar contrast is

shown in the matter of climate. The point of Buchan ended by Kinnaird Head

has the name of being the coldest part of the kingdom, but farther up the

Moray Firth, the counties of Moray and Nairn are so situated and sheltered

as to be more genial than most of England. Forres, which Shakespeare

vainly imagined as a bleak and blasted heath "fit for murders, treasons,

stratagems," has in fact the mean climate of London, cooler in summer,

warmer in winter; and the whole district vies with East Norfolk for the

honour of being Britain's driest corner, so that the Forres Hydropathic,

with its miles of pine-wood walks, makes both a winter and a summer

resort, while a light and porous soil supports fat farming.

The country has many beauty spots also, even among its

lowland features, swelling to the Highlands of Brae Moray, from which

Wolves of Badenoch once swept down upon its folds as Roderick Dhus upon

the Forth's "waving fields and pastures green." The Findhorn, in whose

valley Gordons and Cummings have met lovingly, Professor Blackie calls

"one of the finest stretches of dark mountain water and picturesque wood

in the Highlands." Mr. Charles St. John is eloquent in praise of this

river, where he made so careful studies in natural history. Rising in a

wild solitude, it leaves the open ground to hide its charms among noble

forests and beneath steep cliffs, at whose foot the angler may have to run

for his life, its sudden spates now pressed up in a gorge a few feet wide,

then making a bore-like wave on such a dark basin as that of the old

Bridge of Dulsie, "shut in by grey and fantastic rocks, surmounted with

the greenest of grass swards, with clumps of the ancient weeping birches

with their gnarled and twisted stems, backed again by the dark pine trees.

The river here forms a succession of very black and deep pools, connected

with each other by foaming and whirling falls and currents, up which in

the fine, pure evenings you may see salmon making curious leaps." Another

notable reach shows the grounds of Altyre with its heronry. From these

wooded gorges, so rich in finned and feathered life, the river emerges on

a tamer plain, to enter the sea by the Sahara of Culbin, a singular

coast-line, where cultivated fields have been long ago overwhelmed by

sandhills, banks of shingle, and piles of stones, all barren but for

patches of bent and broom, sheltering huge foxes, hares, and rabbits, that

sally forth to prey upon the farms behind, like any Highland chieftain.

Moray and Nairn thus present a fine variety of scenery, 'dotted by ancient

mansions like Darnaway Castle, with its hall that holds a thousand armed

men, and Cawdor Castle, which one legend makes the scene of Macbeth's

murder. No part of Scotland indeed, has more ruined shrines and

strongholds than the old Moravia, a name once extending beyond the

present bounds of Moray alias Elgin.

Elgin, the town, built of a warm, yellow sandstone that

helps it to a cheerful look, may call itself a city in right of what seems

to have been the noblest Cathedral in Scotland, violated by wild

Highlandmen when this lowland strip too much invited plunder and ravage.

The town has other ruins to show, besides those of Pluscarden Priory some

miles off, and of Spynie Palace on the way

Strath Glass, Inverness-shire

to Lossiemouth, Elgin's rising bathing-place, whose

name should be familiar to readers of George MacDonald's novels. A little

farther along the coast, Nairn, which a Scots king boasted for so long as

to have one end in the Highlands, the other in the Lowlands, is now able

to hold itself up as the "Brighton of the North," recommended by a mild

climate, and by golf-links on the shore, not perched on diabolic downs, as

behind the Londoner's resort.

Gouty southrons may well find their way so far north,

but they do ill to pass by the recesses of this country, now that the

Highland Railway cuts straight across from Aviemore to Inverness. Grantown

above Speyside, indeed, is much sought as a high and dry health resort.

Another place that begins to put in a claim to the same favour is

Tomintoul, at the south end of Banff, the loftiest village in the

Highlands, a hundred feet or so higher than Buxton, and with a chalybeate

well that would work fashionable cures if it could only get a London

doctor to patronise it, while the sub-Alpine site and the mainly Catholic

population might help to give an illusion of Swillingheim - am - Fluss

or Argent les Eaux. A very illustrious author expressed the

picturesqueness of Tomintoul by calling it the "dirtiest, poorest village

in the whole of the Highlands," but that was a generation ago, and the

Tomintoulers are not likely to insist on perpetuating such a compliment,

as Aberdeen solicitors to this day take the higher style of Advocates,

because once so addressed by King James. A more famous spring, as yet, of

this region rises in a distillery which does not want a vates sacer—Fairshon

had a son who married Noah's daughter, And nearly spoilt ta Flood, by

drinking up ta water, Which he would have done, I verily believe it, Had

ta mixture been only half Glenlivet.

But we have jumped over Banff, which may resent being

taken for an appendage of Aberdeen,—long, narrow strip squeezed in between

Moray and Mar, as it runs up from its northern cliff face, set with

fishing villages, to the grand Highlands of Deeside. Banff has a bad name

among Scottish counties for a certain fault of morals which has been

charged upon all Scotland, though as a matter of fact it attaches only to

some parts, and pleas may be given in excuse: for one, the custom of such

irregular unions as under the name of "handfasting" were long winked at in

this corner; for another, the accommodating Scottish law that wipes out by

legal marriage a transgression too lightly treated by local opinion, as

not by Jean Armour's lover when, now and then, his song turned out a

sermon. In other respects Banff may pose as a homespun Arcadia. Some

twenty years ago, when I knew it, there were not thirty policemen in the

whole county, and the county town was hard put to it to confine prisoners

for a single night. The only familiar crime was that wont to be solemnly

indicted before the Sheriff as "Making a great noise, opposite, or nearly

opposite the Free Church Manse, cursing and swearing, and challenging to

fight," i.e. in the blunter English of southern police courts,

being drunk and disorderly; then it would be a point of legal acumen not

to fine the almost always repentantly avowing offender more than he was

likely to have at command.

The authorities stood in dread that some Englishman or

the like would break the law more seriously, as happened when a vagrant

conjuror with an Italian name, but speaking in a strong Whitechapel

accent, conjured a pair of boots into his illegal possession, and had to

be sent all the way to Elgin at the expense of the county. Later on, Banff

got a jail of its own opened, which I one day visited and found the only

captive sociably doing a job of work for the keeper's wife. One case of

theft, indeed, was not unknown, that of boys brought into illicit

relations with apples or the like ; but when an urchin was sentenced to be

whipped for such puerile weakness, the small police force, with the fear

of his mother in their eyes, struck, or rather refused to strike, and I

believe the culprit went scot-free.

The absence of vulgar crime is still more marked in the

Highlands, where, but for whisky and religious zeal, there would be little

need of magistrates. "Ye see, if they stole anything, they couldn't get it

off the island," a Bute cynic once explained to me ; but on the mainland

opposite, I have known the ladies of a family leave their bathing dress

hanging over the hedge by the roadside for weeks together. It was only on

the grand and gallant scale that John Highlandman made a confusion between

meum and tuum. But a distinctly litigious disposition in

trifles keeps northern lawyers from starving among clients who, like

Bartoline Saddletree and Peter Peebles, often cherish a strong amateur

interest in law. In Dandie Dinmont's country, we know, a man was "aye the

better thought o' for having been afore the Feifteen."

Now that everybody subscribes to an Encyclopaedia, it

may not be necessary to remind readers how the Scots law is founded on the

Roman, and how the practice of courts differs north and south of the

Tweed. The administration of justice in Scotland seems now an example to

England, whatever it may have been in the past. Feudalism died slow here.

Baron courts continued to be held to our own day, though shorn of such

unjust privilege as that by which the lord's bailie decided questions

between himself and his tenants. There was a time when only high treason

was withheld from the jurisdiction of these private Solons. Then they lost

power to adjudicate in the "four pleas of the crown,"—murder, rape,

robbery, and arson, unless in the case of the slayer taken red-hand or the

thief infang with the stolen property in his possession within the

barony bounds. So late as 1707 Lord Drummond was good enough to "lend" his

executioner to the city of Perth. After Culloden, hereditary judges like

the Baron of Bradwardine were wholly deprived of the right of furca et

fossa, the drowning of female and hanging of male offenders. Yet a

generation ago the dispensers of minor justice in certain towns were the "bailies"

of the superior, whom in one case I have known to be an Australian

squatter and his distant deputy a respectable carpenter, while in such a

town as Dalkeith, the Duke of Buccleuch appointed an able lawyer as

permanent magistrate. The adoption of the Police Act brought this state of

things to an end ; and the baron's judicial rights, if not formally

abolished, have practically dwindled out of existence.

The part of police magistrate and county court judge is

doubled by the sheriff, an official whose title may be a

A Peep of the Grampians, Inverness-shire

stumbling-block to Englishmen, and still more to

inquiring foreigners like Count Smalltork. Nothing is apter to perplex our

Continental neighbours than the irregularities of our constitution, the

overlapping of boundaries, the general want of such symmetrical and

consistent arrangement as recommends itself to the Latin or the

well-drilled Teuton mind. What a pitfall for the foreign student of our

institutions lies in the fact of a sheriff being an honorary dignitary in

an English county, an elected constable in an American one, but a paid and

permanent judge north of the Tweed ! The shire reeves here were in feudal

times hereditary lieutenants of the Crown, who, as the baron handed over

judicial authority to his clerkly bailie, appointed legal representatives,

still entitled Sheriffs Depute, also known as Sheriffs Principal, as they

have come to be. These well-paid offices are prizes of the bar, held by

successful advocates in Edinburgh, who only in special cases or by way of

appeal are called to judgment. The everyday work of minor justice, civil

and criminal, is done by resident paid officials, called Sheriffs

Substitute, each, in his own district, wearing a halo of authority as "the

Sheriff," usually an advocate who has resigned the risks of practice to

devote himself to this safer if less ambitious career, as is the case with

the French magistracy. There are also Justices of the Peace, as in

England, but these do not come so much before the public.

It need hardly be said that such a professional judge,

assisted in important criminal cases by a jury, and checked in civil suits

by right of appeal to his principal, makes a clearer fountain of justice

than the Great Unpaid of an English Bench, who with the best intentions as

to fairness must often depend on their clerk for law. In some points of

procedure, too, the Scottish system sets a good example to the English.

Prosecutions are not left in private hands, but are conducted by a public

official. The Procurator-Fiscal is the Attorney-General of the Sheriff's

Court, also performing the duties of Coroner without the meddling of a

jury or reporters, though in late years public inquests in certain cases

of death have been introduced into Scottish practice. Petty offenders are

disposed of by the Sheriff off-hand. More serious charges he remits to the

consideration of the Crown officers in Edinburgh, who decide before what

court the prisoner shall be tried. The first step is his being brought to

private audience of the Sheriff, who, taking care that he do not prejudice

his cause, invites him to tell his story, often the only way of getting at

the real facts. Another practical arrangement is that of a "pleading

diet," at which criminals with no defence have a chance of submitting to

the law and being sentenced with as little ado as may be.

While certain crimes, made heinous by the law of Moses,

are still marked on the Scottish statute-book as to be punished with

Draconian severity, and while in "good old days" the gallows, the lash,

and the branding-iron were as freely used as south of the Border, the

administration of the law here has come to be notably mild. Executions are

rare, as, indeed, are cases of premeditated murder. In criminal trials, a

Scottish jury numbers fifteen, and their verdict is that of the majority.

Perhaps a deeper sense of the issues of life and death begets a stronger

reluctance to send a fellow-man to the scaffold, and often prompts the

verdict of "Not proven," by which so many a criminal goes free yet hardly

stainless.

From Aberdeen to Inverness there are three railway

routes over an entanglement of Highland Railway and Great North of

Scotland branches that have their main knot at Elgin. One line runs from

Banff along the Moray Firth, giving fine views across to the opposite

shore of Cromarty. Another turns up the Spey, and by this beautiful strath

would bring us into the heart of the Highlands. The Speyside line

considerately does not hurry passengers through its picturesque

environments. There is a legend about this railway that the town council

of Elgin—no wiser in their generation than Oxford and Cheltenham—sent up

to London a deputation to oppose it in Parliament, when a Cockney crier

made such strange work of the names Elgin and Craigellachie, that the

worthy citizens sat on unconscious that the bill was being passed without

question.

The Speyside line has ways of its own, or had in former

days, when I once remonstrated with a clerk who had given me, unasked, a

return ticket, and he drily answered, "Ye needn't take a return unless ye

like; but it's cheaper"—as it was, by five shillings! At one stage of our

journey, the meeting of a Presbytery or some such function swelled the

company in the single carriage to nearly a score, which so much exercised

the mind of an elder that I heard him remark to a minister, "Doesna this

remind ye, sir, of the saying of Daniel the prophet, 'many shall run to

and fro'?" As if exhausted by its unusual burden, the train stopped

some couple of hours at Craigellachie, giving one time to make a "Spey

cast," but for the want of license and tackle. At the end of nearly a

day's journey from Banff, I reached the Boat of Garten, too late for any

southward train that evening. Like other "boats" and "bridges" of the

Highlands, this has a snug little inn, enlarged I fancy since then, when

it had only one good bedroom, in which more than one crowned head has lain

to rest. A friend of mine was occupying this when a telegram announced the

arrival of the Empress of the French. Of course he turned out, then the

people of the house sought his advice in adorning the chamber. He found

them hastily fastening up over the Empress' bed their most striking work

of art, which happened to be a picture of the battle of Waterloo! Much

more like Celtic courtesy was the conduct of William Black's Highland

veteran, who scrupled to wear his tartan trews before a Frenchwoman, for

fear of reviving sore memories.