The dawn broadens, the mists roll away to show a

northward-bound traveller how his train is speeding between slopes of

moorland, green and grey, here patched by bracken or bog, there dotted by

wind-blown trees, everywhere cut by water-courses gathering into gentle

rivers that can be furious enough in spate, when they hurl a drowned sheep

or a broken hurdle through those valleys opening a glimpse of mansions and

villages among sheltered woods. Are we still in England, or in what at

least as far back as Cromwell's time called itself "Bonnie Scotland"? It

is as hard to be sure as to make out whether that cloudy knoll on the

horizon is crowned by a peat-stack or by the stump of a Border peel.

Either bank of Tweed and Liddel has much the same

aspects. An expert might perhaps read the look or the size of the fields.

Could one get speech with that brawny corduroyed lad tramping along the

furrows to his early job, whistling maybe, as if it would never grow old,

an air from the London music-halls, the Southron might be none the wiser

as to his nationality, though a fine local ear would not fail to catch some difference of burr and

broad vowels, marked off rather by separating ridges than by any legal

frontier, as the lilting twang of Liddesdale from the Teviot drawl.

Healthily barefooted children, more's the pity, are not so often seen

nowadays on this side of the Border, nor on the other, unless at Brightons

and Margates. The Scotch "bonnet," substantial headgear as it was, has

vanished; the Scotch plaid, once as familiar on the Coquet as on the

Tweed, is more displayed in shop windows than in moorland glens, now that

over the United Kingdom reigns a dull monotony and uniformity of garb.

Could we take the spectrum of those first wreaths of smoke curling from

cottage chimneys, we might find traces of peat and porridge, yet also of

coal and bacon. Yon red-locked lassie turning her open eyes up to the

train from the roadside might settle the question, were we able to test

her knowledge whether of the Shorter Catechism or of her "Duty towards her

Neighbour." It is only when the name of the first Scottish way-station

whisks by, that we know ourselves fairly over the edge of " Caledonia

stern and wild"; and our first thought may well be that this Borderland

appears less stern than the grey crags of Yorkshire, and less wild than

some bleak uplands of Northumberland.

What makes a nation ? Not for long such walls as the

Romans drew across this neck of our island, one day to point a moral of

fallen might, and to adorn a tale of the northern romancer who by its

ruins wooed his alien bride. Not such rivers as here could be easily

forded by those mugwump moss-troopers that sat on the fence of Border law,

and—

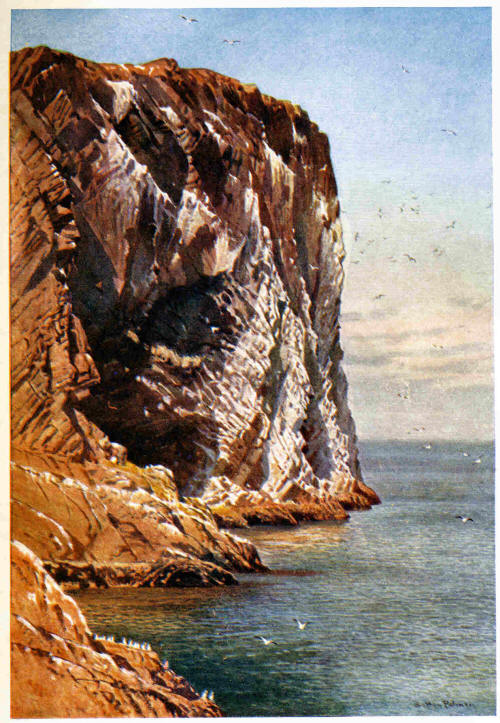

Tantallon Castle, on coast of Haddingtonshire

"Sought the beeves to make them broth

In England and in Scotland both."

Is it race? Alas for the ethnologic historian, on its

dim groundwork of Picts and Celts—or what?—Scotland shows a still more

confusing pattern of mingled strains than does the sister kingdom! To both

sides of the Border such names for natural features as Cheviot, Tweed, and

Tyne, tell the same tale of one stock displaced by another that built and

christened its Saxon Hawicks, Berwicks, Bamboroughs, and Longtowns upon

the Pens and Esks of British tribes.—Is it a common speech? But from the

Humber to the Moray Firth, along the east side of Britain, throughout the

period of fiercest clash of arms, prevailed the same tongue, split by

degrees into dialects, but differing on the Forth and the Tyne less than

the Tyne folks' tongue differed from that of the Thames, or the speech of

the Forth from that of the Clyde mouth. So insists Dr. J. A. H. Murray,

who of all British scholars was found worthy to edit the Oxford English

Dictionary, that has now three editors, two of them born north of the

Tweed, the third also in the northern half of England. Scottish "wut"

chuckles to hear how, when the shade of Boswell pertly reported to the

great doctor that his post as Lexicographer-General had been filled by one

who was at once a Scotsman and a dissenter, all Hades shook with the

rebuke, "Sir, in striving to be facetious, do not attempt obscenity and

profanity!" —or ghostly vocables to such effect.

Is it loyalty to a line of princes that crystallises

patriotism? That is a current easily induced, as witness how the

sentiments once stirred by a Mary or a Prince Charlie could precipitate

themselves round the stout person of George IV.—Is it religion? Kirk and

Covenant have doubtless had their share in casting a mould of national

character; but the Border feuds were hottest among generations who seldom

cared to question "for gospel, what the Church believed."—Is it name?

Northerners and Southerners were at strife long before they knew

themselves as English and Scots.

By a process of elimination one comes to see how

esprit de corps seems most surely generated by the wont of standing

shoulder to shoulder against a common foe. Even the shifty baron, "Lucanus

an Apulus anceps," whose feudal allegiance dovetailed into both kingdoms,

that professional warrior who "signed on," now with the northern, now with

the southern team, might well grow keen on a side for which he had won a

goal, and bitter against the ex-comrades who by fair or foul play had come

best out of a hot scrimmage. Heartier would be the animosity of

bonnet-lairds and yeomen, between whom lifting of cattle and harrying of

homes were points in the game. Then even grooms and gillies, with nothing

to lose, dutifully fell into the way of fighting for their salt, when

fighting with somebody came almost as natural to men and boys as to collie

dogs. So the generations beat one another into neighbourly hatred and

national pride; till the Border clans half forgot their feuds in a larger

sentiment of patriotism; and what was once an adventurous exercise, rose

to be a fierce struggle for independence. The Borderers were the

"forwards" of this international sport, on whose fields and strongholds

became most hotly forged the differences in which they played the part of

The Bass Rock, Firth of Forth, off the coast of Haddingtonshire

hammer and of anvil by turns. Here, it is said, between

neighbours of the same blood, survive least faintly the national

resentments that may still flash up between drunken hinds at a fair.

Hardly a nook here has not been blackened and bloodstained, hardly a

stream but has often run red in centuries of waxing and waning strife

whose fiery gleams are long faded into pensive memories, and its ballad

chronicles, that once "stirred the heart like a trumpet," can now be sung

or said to general applause of the most refined audiences, whether in

London or Edinburgh.

The most famous ground of those historic encounters

lies about the East Coast Railway route, where England pushes an

aggressive corner across the Cheviots, and the Tweed, that most Scottish

of rivers, forms the frontier of the kingdoms now provoking each other to

good works like its Royal Border Bridge. Beyond it, indeed, stands

Berwick-upon-Tweed, long the football of either party, then put out of

play as a neutral town, and at last recognised as a quasi-outpost of

England, whose parsons wear the surplice, and whose chief magistrate is a

mayor, while the townsfolk are said to pride themselves on a parish

patriotism that has gone the length of calling Sandy and John Bull

foreigners alike. This of course is not, as London journalists sometimes

conceive, the truly North Berwick where a prime minister might be seen

"driving" and "putting" away the cares of state. That seaside resort is a

mushroom beside Berwick of the Merse, standing on its dignity of many

sieges. The Northumberland Artillery Militia now man the batteries on its

much-battered wall, turned to a picturesque walk; and the North British

and North Eastern Railways meet peacefully on the site of its castle,

where at one time Edward I. caged the Countess of Buchan like a wild

beast, for having dared to set the crown upon Bruce's head. At another, it

was in the hands of Baliol to surrender to an Edward as pledge of his

subservience; and again, its precincts made the scene of a friendly

spearing match between English and Scottish knights, much courtesy and

fair-play being shown on both sides, even if over their cups a perfervid

Grahame bid his challenger "rise early in the morning, and make your peace

with God, for you shall sup in Paradise!" who indeed supped no more on

earth.

The North British Railway will carry us on near a stern

coast-line to Dunbar, whose castle Black Agnes, Countess of March,

defended so doughtily against Lord Salisbury, and here were delivered so

signally into Cromwell's hands a later generation of Scots "left to

themselves" and to their fanatical chaplains; then over a land now swept

by volleys of golf balls, to Pinkie, the last great battlefield between

the kingdoms, where also, almost for the last time, the onrush of Highland

valour routed redcoat soldiery at Prestonpans. But tourists should do what

they do too seldom, tarry at Berwick to visit the tragic scenes close at

hand. In sight of the town is the slope of Halidon Hill, on which the

English took their revenge for Bannockburn. Higher up the Tweed, by

the first Suspension Bridge in the kingdom, by "Norham's castled steep,"

watch-tower of the passage, and by Ford Castle where the siren Lady Ford

is said to have ensnared James IV., that unlucky "champion of the dames,"

a half-day's walk brings one to Flodden, English ground indeed, but the

grave of many a Scot. Never was slaughter so much mourned and sung as that

of the "Flowers of the Forest," cut down on these heights above the Tweed.

The land watered with "that red rain is now ploughed and fenced; but still

can be traced the out-now ploughed and fenced; lines of the scene about

the arch of Twizel Bridge on which the English crossed the Till, as every

schoolboy knew in Macaulay's day, if our schoolboys seem to be better up

in cricket averages than in the great deeds of the past, unless prescribed

for examinations.

Battles like books, have their fates of fame. Flodden

long made a sore point in Scottish memory ; yet, after all, it was a

stunning rather than a maiming defeat. A far more momentous battlefield on

the Tweed, not far off, was Carham, whose name hardly appears in school

histories, though it was the beginning of the Scotland of seven centuries

to come. It dates just before Macbeth, when Malcolm, king of a confused

Scotia or Pictia, sallied forth from behind the Forth, and with his ally,

Prince of Cumbria on the Clyde, decisively defeated the Northumbrians in

1018, adding to his dominions the Saxon land between Forth and Tweed, a

leaven that would leaven the whole lump, as Mr. Lang aptly puts it. Thus

Malcolm's kingdom came into touch with what was soon to become feudal

England, along the frontier that set to a hard and fast line, so long and

so doughtily defended after mediaeval Scotland had welded on the western

Cumbria, as its cousin Cambria fell into the destinies of a stronger

realm. Had northern Northumberland gone to England, there would have been

no Royal Scotland, only a Grampian Wales echoing bardic boasts of its Rob

Roys and Roderick Dhus, whose claymores might have splintered against

Norman mail long before they came to be beaten down by bayonets and police

batons.

But we shall never get away from the Border if

we stop to moralise on all its scenes of strife—most of them well

forgotten. Border fighting was commonly on a small scale, with plunder

rather than conquest or glory for its aim; like the Arabs of to-day,

those fierce but canny neighbours were seldom in a spirit for needless

slaughter, that would entail fresh blood-feuds on their own kin. The

Border fortresses were many, but chiefly small, designed for sudden

defence against an enemy who might be trusted not to keep the field long.

On the northern side large castles were rare; and those that did rise,

opposite the English donjon keeps, were let fall by the Scots themselves,

after their early feudal kings had drawn back to Edinburgh. In the long

struggle with a richer nation, they soon learned to take the "earth-born

castles" of their hills as cheaper and not less serviceable strongholds.

The station for Flodden, a few miles off, is

Coldstream, at that "dangerous ford and deep" over which Marmion led the

way for his train, before and after his day passed by so many an army

marching north or south. The Bridge of Coldstream has tenderer memories,

pointed out by Mr. W. S. Crockett in his Scott Country. This

carried one of the main roads from England, and the inn on the Scottish

side made a temple of hasty Hymen, where for many a runaway couple were

forged bonds like those more notoriously associated with the blacksmith of

Gretna Green. Their marriage jaunts into the neighbour country were put a

stop to only half a century ago, when the

Neidpath Castle, Peebleshire

benefits of Scots law, such as they were, became

restricted to its own inhabitants. English novelists and jesters have made

wild work with the law, by which, as they misapprehend, a man can be

wedded without meaning it; one American story-teller is so little

up-to-date as to marry his eloping hero and heroine at Gretna in our time.

The gist of the matter is that while England favoured the masculine

deceiver, fixing the ceremony before noon, it is said, to make sure of the

bridegroom's sobriety, the more chivalrous Scots law provided that any

ceremony should be held valid by which a man persuaded a woman that he was

taking her to wife. No ceremony indeed was needed, if the parties lived by

habit and repute as man and wife. The plot of Colonel Lockhart's Mine

is Thine, one of the most amusing novels of our time, turns on a noted

case in which an entry in a family Bible was taken as a sufficient proof

of marriage. It is only gay Lotharios who might find this easy coupling a

fetter ; though in the next generation, especially if it be careless to

treasure family Bibles, there may arise work for lawyers, a work of

charity when the average income of the Scottish Bar is perhaps five pounds

Scots per annum.

Gretna Green, of course, lies on the western high-road

from England, beside which the Caledonian Railway route from Carlisle

enters Scotland, soon turning off into a part of it comparatively

sheltered from invasion by the Solway Firth, whose rapid ebb and flow make

a type of many a Gretna love story. This side too, has often rung

with the passage of armed men. At Burgh-on-Sands, in sight of the Scottish

Border, died Edward I., bidding his bones be wrapped in a bull's hide and

carried as bugbear standard against those obstinate rebels. The rout of

Solway Moss made James V. turn his face to the wall, his heart breaking

with the cry, "It came with a lass and it will go with a lass!" And the

Esk of the Solway was seldom "swollen sae red and sae deep" as to daunt

hardy lads from the north who once and again

"Swam ower to fell English ground,

And danced themselves dry to the pibroch's sound."

These immigrants, unless they found six feet of English

ground for a grave, seldom failed to go "back again," perhaps with an

English host at their heels. Prince Charlie's army passed this way on its

retreat from Derby. But this side of the Borderland is less well

illustrated by stricken fields and sturdy sieges. It has, indeed, no lack

of misty romance of its own, such as an American writer dares to bring

into the light of common day by adding a sequel to Lady Heron's ballad, in

which the fair Ellen is made to nurse a secret grudge at last confessed :

she could not get over, even on any plea of poetic license, that rash

assertion:

"There are maidens in Scotland more lovely by far

Who would gladly be bride to the young Lochinvar!"

"Fosters, Fenwicks, and Musgraves," how they rode and

they ran on those hills and leas in days unkind to "a laggard in love and

a dastard in war"! These names belong to the English side, as does Grahame

in part. Elliot and Armstrong, Pringle and Rutherford, Ker and Home,

Douglas, Murray, and Scott, are Scottish Border clans, who kept much

together as in the Highlands. "Is there nae kind Christian wull gie me a

night's lodging?" begged a tramp on the Borders, and had for rough answer,

"Nae Christians here; we're a' Hopes and Johnstones!" a jest transmuted

farther north into the terms of a black Mackintosh and red Macgregors.

The first name of fame passed on the Caledonian line is

Ecclefechan, birthplace of Thomas Carlyle, now a prophet even in his own

country, but it is recorded how a devout American pilgrim of earlier days

found no responsive warmth in the minds of old neighbours. "Tam

Carlyle—ay, there was Tam!" admitted an interrogated native. "He went tae

London; they tell me he writes books. But there's his brither Jeems—he was

the mahn o' that family. He drove mair pigs into Ecclefechan market than

ony ither farmer in the parish!" Tom had carried his pigs to a better than

any Dumfriesshire market. If we turned west by the Glasgow and

Southwestern Railway, we should soon come among the shrines of Burns and

the monuments of Wallace. But let us rather take the central route, on

which flourishes a greener memory.

The "Waverley" route from Carlisle, a central one

between those East and West Coast lines, so distinguishes itself as

passing through the cream of the country associated with Sir Walter Scott,

its first stage being the wilds of Liddesdale, where he spent seven

holiday seasons collecting the Border Minstrelsy. This district, where

"every field has its battle and every rivulet its song," can boast of many

singers. From the days of Thomas the Rhymer comes down its long succession

of ballad-makers who "saved others' names but left their own unsung." At

Ednam was born James Thomson, bard of The Seasons and of "Rule,

Britannia," who surely deserves a less prosaic monument than here recalls

him. From Ednam, too, came Henry Lyte, a name not so familiar, but how

many millions know his hymn "Abide with me"! Some of Horatius Bonar's

hymns were written during his ministry at Kelso. About Denholm were the

"Scenes of Infancy" of John Leyden, poet and scholar, cut off untimely.

Near his humble home, now turned into a public library, is the lordly

house of Minto, one of whose daughters wrote the "Flowers of the Forest."

Thomas Pringle, the South African poet, was born at Blakelaw, near Yetholm,

the Border seat of gipsy kings. Home, the author of Douglas, is

said to have come from Ancrum, which can more certainly claim Dr. William

Buchan of Domestic Medicine renown. Riddell, author of "Scotland

Yet," began life as a Teviot shepherd. If we may touch on living names,

was not Mr. Andrew Lang born among the "Soutars of Selkirk," who has gone

so far ultra crepidam? But indeed a whole page might be filled with

a bare catalogue of the bards of Tweed and Teviot.

The genius loci, greatest of all, while born in

Edinburgh, sprang from a Border family of "Scotland's gentler blood." The

cradle of his race was in Upper Teviotdale, near Hawick, that thriving

"Glasgow of the Borders," among whose busy mills the old Douglas Tower

still stands as an hotel, and rites older than Christian Scotland are

cherished at its time-honoured Common Riding. Not far off are Harden, home

of Wat Scott the reiver, and Branxholme, that after being repeatedly

burned by the English, bears an inscription of its rebuilding by a Sir

Abbotsford, Roxburghshire

Walter Scott of Reformation times, whose namesake and

descendant would make its name known so widely. At Sandyknowe farm,

between the Eden and the Leader Water, he lived as a sickly child in his

grandparents' charge, and under the massive ruin of Smailholm Tower, drank

in with reviving health the inspiration of Border lore and romance—

"Ever, by the winter hearth,

Old tales I heard of woe or mirth,

Of lover's sleights, of ladies' charms,

Of witches' spells, of warriors' arms;

Of patriot battles, won of old

By Wallace wight and Bruce the bold;

Of later fields of feud and fight,

When, pouring from their Highland height,

The Scottish clans, in headlong sway,

Had swept the scarlet ranks away.

While stretch'd at length upon the floor,

Again I fought each combat o'er,

Pebbles and shells, in order laid,

The mimic ranks of war display'd;

And onward still the Scottish Lion bore,

And still the scatter'd Southron fled before."

Later on, the old folks being dead, his sanatorium

quarters were shifted to his aunt's home at Kelso, where also an uncle

bought a house, inherited by the lucky poet. For a time he attended the

Grammar School, whose pupils had for playground the adjacent ruins of the

Abbey, so roughly handled in Border wars and by iconoclastic zealots. This

boy had other resources than play, who could forget his dinner in the

charms of Percy's Reliques; and his lameness did not hinder him

from roaming over the beautiful country in which Tweed and Teviot meet.

Their confluence encloses the ruins of Roxburgh Castle, once a favourite

royal residence and strong Border fortress, before whose walls James II.,

trying to wrest it back from the English, was killed by the bursting of

one of those new-fangled "engines"; that were to break down moated

castles, replaced by such sumptuous mansions as Floors, the modern

chateau of the Duke of Roxburghe. Roxburgh town has disappeared more

completely than its castle, its name surviving in that of the picturesque

Border shire where, off and on, Scott spent much of his youth,

photographing on a sensitive mind the scenes he has made famous, and

getting to know the flesh-and-blood models of Meg Merrilies, Edie

Ochiltree, Old Mortality, Dandie Dinmont, Josiah Cargill, and other

"characters" that but for him might now be forgotten.

Kelso stands almost on the site of Roxburgh, but its

place as county town is taken by Jedburgh, guard of the "Middle March,"

farther to the south, yet not so near the crooked border line. It stands

upon a tributary of the Teviot, among "Eden scenes of crystal Jed,"

flowing down from the Cheviots. Tourists do not know what they miss by

grudging time to divagate on the branches connecting the two main lines of

the North British Railway. Jedburgh, birthplace of scientific celebrities,

Sir David Brewster and Mrs. Somerville, has another grand Abbey, that

suffered much from early English tourists; and its jail occupies the site

of a vanished royal castle. In this old seat of "Jeddart justice," Scott

began his career at the Bar, by the defence of such a poacher and

sheep-stealer as his own forebears had been on a bolder scale. Here a few

years later, he met Wordsworth in the house recently marked by a memorial

tablet ; and other dwellings are pointed out as having housed Queen Mary

and Prince Charlie, while Burns has left a warm record of his visit, so

many of Scotland's idols has Jedburgh known, and may well reproach the

hasty travellers who pass it by.

The young advocate did not waste much of his genius on

defending sheep-stealers and the like ; but in those halcyon days of

patronage, through the influence of his chief, the Duke of Buccleuch, he

soon got the snug berth of Sheriff of Selkirk. This brought him to live at

Ashestiel on the Tweed, where he spent his happiest days, writing his best

poems, and beginning Waverley, to be laid by and forgotten for

years. Selkirk, too, has the misfortune of lying off the main line; but

strangers would do well to turn aside here for the wild pastoral scenes of

St. Mary's Loch and the "Dowie Dens of Yarrow." Too many, like Wordsworth,

put off this trip to rheumatic years; yet it may be easily done by the

coach routes from Selkirk and from Moffat on the Caledonian line, that

meet at Tibbie Shiels' Inn, whose visitors' book enshrines such a

collection of autographs; and its homely fame scorns the pretensions of

the new "hotel." This is the heart of Ettrick Forest, where stands a

monument of its shepherd, James Hogg, unfairly caricatured as the genial

buffoon of the Noctes, but second only to Burns as a popular poet,

and best known over the English-speaking world by his "Bird of the

wilderness, blithesome and cumberless." All the schooling he had was a few

months early childhood; he taught himself to write on slate stones of the

hillside where he herded cows, and this art he had to relearn when he

first tried to sing of green Ettrick—

"In many a rustic lay,

Her heroes, hills, and verdant groves;

Her wilds and valleys fresh and gay,

Her shepherds' and her maidens' loves."

The North British junction for Selkirk is at Galashiels,

another thriving woollen town, whose mills may not have improved the

physique of the "braw lads of Gala Water." Before reaching this, the main

line, holding up the Tweed where it is looked down upon by a colossal

statue of Wallace, passes two more of David I.'s quartet of Abbeys, so

that the tourist has no excuse for not visiting Dryburgh and Melrose.

Melrose, indeed, is a tourist shrine, that owns a somewhat sheltered

climate, with natural charms enough to fill its adjacent Hydropathic and

the hotels about the Abbey and the Cross, nucleus of a group of Tweedside

hamlets, to which warm red stone, sometimes filched from the ruins, gives

a snug and cheerful aspect ; then the nakedness of the slopes, held by

Scott a beauty, though he laboured to clothe it with plantations, hides

nooks like that Rhymer's Glen, where True Thomas was spirited away by the

Fairy Queen, and that Fairy Dean in which the White Lady of Avenel

appeared to Halbert Glendinning. Above rise the triple Eildon Hills, in

whose caverns Arthur and his knights lie sleeping, and from the top, as

our Last Minstrel boasted, can be seen more than forty spots famed in

history or song.

Of Melrose Abbey, the finest remains of Scottish

ecclesiastical architecture in its golden age, and of its

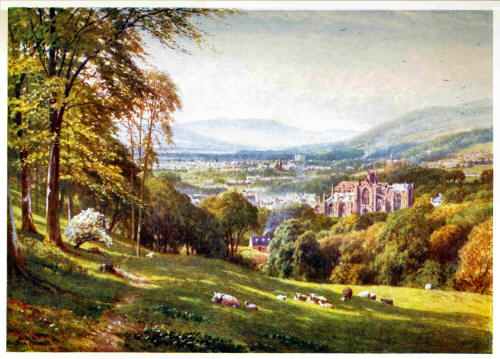

Melrose, Roxburghshire

illustrious tombs, let the guide-books speak, and the

romance that deals with this neighbourhood of "Kenna-quhair," an alias

plagiarised by Carlyle in his Weissnichtwo. Visiting it "by

pale moonlight" or otherwise, few will not turn three miles up the river

to that other show-place, Abbotsford, the Delilah of his imagination that

bound Scott in withs of care and set him to toiling for Philistines. The

baronial mansion, now overlooked by outlying villas of Galashiels, was all

his own creation, and most of the trees were planted by himself, in the

absorbing process that began with buying a hundred ill-famed acres, and

ended with such unfortunate success in making, as he said, "a silk purse

out of a sow's ear." When one thinks what it cost him, this exhibition of

artificial feudalism has its painful side; yet another Sir Walter, a

romancer of our own generation, declares that it "would make an oyster

enthusiastic." But more moving is the pilgrimage from Melrose down the

Tweed to where, in St. Mary's Aisle of Dryburgh Abbey, the most beautiful

fragment of a noble fane, among the tombs of his kin lies at rest

Scotland's most illustrious son, he who best displayed the warp and woof

that makes the chequered pattern of his country's nature.

When will Cockney revilers learn that Scotland is not

all thrift, caution, and kailyard prose, but a nation showing two main

strains, which Mr. John Morley suggests as the explanation of Gladstone's

complex character? One component may be hard, practical, frugal, in

politics tending to democracy, in religion to logic; but this has been

crossed by a spirit, better bred in the romantic Highlands, that is

generous, proud, quick-tempered, reckless, reverent towards the past,

rather than eager for progress. The painter of Scottish life must

recognise how Fitz-James and Roderick Dhu are countrymen with Bailie Nicol

Jarvie and Andrew Fairservice, how Flora Maclvor is not less a Scotswoman

than Mause Headrigg or Jenny Dennison, and how the Jacobite and the

Presbyterian enthusiasm smacked of the same soil. If one shut one's eye to

half the case, it would be easy to make out that rash impetuosity

flourished beyond the Tweed rather than the thistly prudence taken for a

more congenial crop.

Scott comprehended both of these elements. By birth and

training he belonged to the Saxon, by sympathy to the Celt. If his father

was a douce Edinburgh "writer," one of his forebears had been that "Beardie"

who bound himself never to shave till the Stuarts came back to their own.

Brought up under the dry light of the Revolution Settlement, in his

reminiscences of childhood he transforms a worthy parish minister into a

"Venerable Priest," and in later life he came to be himself little better

than an Episcopalian. It may be owned he had no more religion than became

a Cavalier; even the romance of superstition did not take much hold on

him, and that rhyming "White Lady" has not even a ghostly life on his

page. His favourite heroes are the like of Montrose and Claver-house, yet

he can do justice to the stern virtues of the Covenanters. In the sober

historian mood he duly warns his grandchild how life was galled and

fettered in the good old days, which he was too willing to see couleur

de rose when their picturesque incidents offered themselves to the

romancer. He turns a blind eye, perhaps, too much on the faults of knights

and princes, yet he knows the worth of ploughmen and fisherfolk, and into

Halbert Glendinning's and Henry Morton's mouths he puts sentiments to

which John Bright or Cobden might say amen. He is happiest, indeed, in the

past, when "the wrath of our ancestors was coloured gules," whereas

we have learned, like Parson Adams' wife, to be Christians and take the

law of our enemies. His appetite for imaginary bloodshed is a sore

offence to writers like Mark Twain, who appear less scandalised that a

pork-baron, a corn-lord, or a cotton-king should plot to be rich by

starving children on the other side of the world. But Scott's very

failings reflect the character of his countrymen, who, Highland and

Lowland, have been mighty fighters before the Lord on a much wider field

than from Berwick to John o' Groat's House. The pity is that this

imaginative writer, who knew all characters better than his own, should

have fancied himself a shrewd man of business, a part for which he was too

generous and trustful. Of his personal merits, the most marked is that in

a class of sedentary craftsmen notoriously apt to be irritable, bilious,

jealous, and vainglorious, Walter Scott stands out by hearty, wholesome,

human qualities which present him as the type of a Scottish gentleman.

Whatever record leap to light,

He never shall be shamed!

To have done with the "Scott Country," we should hold

on westward up the Tweed to where its sources almost mingle with those of

the Clyde, below the bold mass of Tinto and other hills that might claim a

less modest title. This route would bring us by the renowned inn of

Clovenfords, "howff" of Christopher North and many another choice spirit,

by Ashestiel, then by Innerleithen, set up as a spa through its claim to

represent St. Ronan's; and so to Peebles, a haunt of pleasure since the

days when James I. wrote of "Peeblis to the play." For some reason or

other, Peebles and Paisley have become butts of Gotham banter, their very

names attracting the sly jests by which Scotsmen love to make fun of

themselves. But neither of them is a town to be sneezed at. Peebles, for

its part, after falling into a rather sleepy state, has been wakened up in

our time through the Tontine "hottle," that so much excited Meg Dods'

scorn ; the huge Hydropathic that has introduced German bath practice into

Scotland ; and the Institution bestowed on the town by William Chambers,

who hence set out to turn the proverbial half-crown into a goodly fortune.

Was it not at this Institution that the local Mutual Improvement Society

gravely debated the question, "Shall the material Universe be

destroyed?" and decided, by a majority of one, in the negative! When Sir

Cresswell Cresswell, from his peculiar bench, laid down the dictum that

marriages between May and December often turned out ill, it must have been

a Paisley statistician who wrote to him for the data on which he founded

his assertion that "marriages contracted in the latter part of the year,

etc." But Paisley has its manufacturing prosperity to fling in the teeth

of calumny; and Peebles has romantic as well as comic associations,

notably its Neidpath Castle and its Manor Water Glen, haunted by memories

of the Black Dwarf.

The leisurely tourist might gain Edinburgh by a

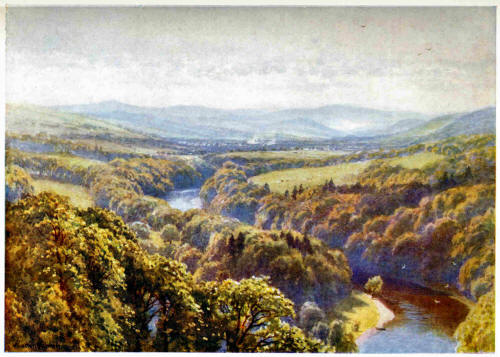

Scott's Favourite view from Bemerside Hill, Roxburghshire

branch line through Peebles, and this route can be

recommended to the hippogriffs of cycles and motors. Beyond the Catrail,

ancient barrier of the Picts or the Britons of Strathclyde, our main

railroad, as its way is, keeps on straight up the course of the Gala,

leaving to its right the dreary Lammermoors; then between the Castles of

Borthwick and Crichton, it enters on the more prosaic Lothian country. To

the left is seen the Pentland ridge, and straight ahead springs up the

cone of Arthur's Seat beaconing us to Edinburgh, goal of the race for

which a Caledonian express will be speeding along the farther side of the

Pentlands.

And not a kilt have we seen yet, since leaving London!

Of this more anon; kilts are not at home on the Borders, though I have

seen one on the Welsh Marches, worn in conjunction with a pith helmet by a

retired Liverpool tradesman. Since "gloves of steel" and "helmets barred"

went out of fashion on Tweedside, the local colour has been that modest

shepherd's plaid displayed in Lord Brougham's trousers to the ribaldry of

Punch, and even that goes out of homely wear. You may buy Scott and

Douglas tartans in the shops, but they seem vain things, fondly invented,

as indeed are some of the patterns now seen in the Highlands. But there

will be a good show of kilts in Edinburgh Castle, where once they were

like to be bestowed in the dungeon:—

Wae worth the loons that made the laws

To hang a man for gear—

To reave o' life for sic a cause

As lifting horse or mare!

And here our North British express, panting through the

fat Lothians, comes to slacken under the castellated walls of that gaol

which tourists are apt to take for the Castle—no true kilts to be looked

for there nowadays, yet perhaps at the Police Court under the head of

drunk and disorderly! So let us leave the Borderland behind with a

quotation from an American writer (Penelope in Scotland) who knows

what's what, and who at first sight fairly loses her heart to Edinburgh,

haars, east winds, and all, that are its thorns in the flesh. "I

hope," she very sensibly says, "that those in authority will never attempt

to convene a Peace Congress in Edinburgh, lest the influence of the Castle

be too strong for the delegates. They could not resist it nor turn their

backs upon it, since, unlike other ancient fortresses, it is but a

stone's-throw from the front windows of all the hotels. They might mean

never so well, but they would end by buying dirk hat-pins and claymore

brooches for their wives; their daughters would all run after the kilted

regiment and marry as many of the pipers as asked them, and before night

they would all be shouting with the noble Fitz-Eustace,

'Where's the coward that would not dare

To fight for such a land?' "